Historical Laboratory Projects

Diplomatic History: Propaganda Donna Landis

Diplomatic history

Definition: According to the Huygens Institute diplomatic history, “aims to piece together the decision-making processes of policy-makers, thereby reconstructing the reality (or ‘truth’) of statecraft”24 Diplomatic history is separate from international relations. Both international relations and diplomatic history look at the complex ties between nations. 23 There are two differences, the first being diplomatic history deals more with trying to gather facts while international relations deals more with creating theories. 23 The second distinction between the two disciplines is international relations is irrelevant if it is not current and up to date while diplomatic history does not need to study current events to be relevant.23 For most of its history diplomatic history has used a very diplomatics (the study of documents, records and archives) methodology, looking at prim

ary official government documents and treaties for most of its source material but that has been slowly changing over the years.6With the end of the Cold War and the increase in non-government players many diplomatic historians are starting to adopt the strategies of other houses of history.

Influenced by Empiricists

The term diploma is tied to official documents, with diplo meaning ‘folded in two’ and ‘ ma ‘ meaning an object.2 As the increase of official international agreements grew so did the need for someone to sort, organize and preserve these documents.2 These documents that were preserved became the main source of information for Leopold Van Ranke. Ranke believed in using primary sources for historical analysis 3 and the documents that were preserved in the Venetian archives, and the reports from ambassadors were the cornerstone of his work.4 Ranke believed in “the prim

acy of foreign policy”5 or the principle that the policies that governments enact with other governments will influence its domestic policy.5

Government Documents

As the politics of the 19th and 20th century developed so did diplomatic history. With the further development of society, the increase of rights and enfranchisement of the public, European governments wanted to justify their foreign policies.6 Governments started publishing their diplomatic correspondence, adding more fuel for diplomatic historians to use.6 The curiosity of the public in the affairs of statesmen and questions about how the country got to its present state made diplomatic history increase in popularity.6 This popularity was further increased in the beginning of the 20th century.

WW1

World War one caused the greatest changes in geopolitics in the 20th century. It caused the fall of four European empires and the destabilization of Europe that caused World War two.8 Part of the cause of World War one was the complex alliances that were formed.8 The question of how the alliances failed to keep Europe out of conflict was asked by diplomatic historians to find the best way to keep peace.6 The idea that you can use history as a tool of peace influenced a lot of diplomatic historians. Most notably diplomatic historian Sir Charles Kingsley Webster, a history professor at Harvard10 and attendee of the Versailles conference11 , who’s knowledge of history played a key role in helping to plan the United Nations.11

Unfortunately, diplomatic history was not only a tool used for peace after World War one it caused debates and academic conflict. While most diplomatic historians at the time wanted to keep to the principles of empiricism some were influenced by the politics of the time.6 Finding out “who was to blame” for the start of World War one became an academic question that was for the most part answered by nationalism.12 This led to countries to publish archival materials to support their side with Germans dema

nding a revision of the Treaty of Versailles.6

Outdated

After World War Two Marxism and social history became popular. 6 There was a movement away from studying the decisions of the upper class and their became more of a focus towards working class people.6The end of World War two not only brought on the rise of Marxism and the study of working class people but the study of nations histories away from colonialism and the study of gender. 3This change in focus was the opposite of what diplomatic history was studying. Unlike Marxism and social history, diplomatic history looked at the decisions of the elites and unlike post colonialists and gender studies diplomatic history looked at the decisions of men in mostly powerful colonizing countries. 6There was also a difference in what sources were preferred, diplomatic history used almost exclusively government documents found in archives whereas the other houses used personal documents, art and even oral histories. This made diplomatic history seem outdated and out of touch.

New Diplomatic History

Diplomatic history took a long time to adopt the strategies of other houses of history. It was not until the 1980s that a call for a change in diplomatic history was made. Gordon A. Craig, a diplomatic historian, and a history professor at Stanford, wanted diplomatic history to investigate the effects politics, social customs, public attitudes had on negotiation. 13 He wanted diplomatic historians to see that diplomats were not always influenced by what was best for their country but that they were human and had human influences.13 New diplomatic history looks at unofficial diplomats and non-state actors like NGOs asking the question of who is considered a diplomat?14

Public diplomacy and Propaganda

A newer subsection of diplomatic history is the history of “public diplomacy”, the name was repurposed by U.S. diplomat Edmund Gullion to distance the U.S government’s actions away from the word “propaganda”.15 Original use of the phrase was to describe new diplomatic actions that were taking place during World War One.17 It was one of the first times that public statements were being made about diplomatic affairs like public calls for peace.17 Woodrow Wilson used the phrase “public diplomacy” to refer to more public discussion of international affairs in his fourteen points, advocating for the people to know about the diplomatic affairs of their nation.17 According to the Center on Public Diplomacy, public diplomacy is seen now as the, “means by which a sovereign country communicates with publics in other countries aimed at informing and influencing audiences overseas for the purpose of promoting the national interest and advancing its foreign policy goals.”15

One of public diplomacy’s core concepts is known as “soft power”. Soft power, according to Joseph Nye is, influence using cultural assets, political ideals, and policies instead of coercion or payments.15 “Soft power” has two categories, the first is cultural communication, where the goal is to foster a better image for the country without a set goal.16 The result of cultural communication is more long term.16 The second category of “soft power” is political advocacy where a nation tries to build support in another nation for a specific policy, the goal is to achieve short term action.16

Public Diplomatic History: Just the Beginning

The study of public diplomatic history is extremely recent. The Cold War was one of the first times that nations started to actively use “soft power” as a strategy to convince the public of other nations of their cause.20 What is important to note is that propaganda has been used for centuries as a way for nations to motivate their own people, this was one of the first times that it was used to motivate people outside of the nation. The reason why nations were involved in the Cold War, sometimes referred to as “The Propaganda War”, was that it was the start of using the threat of nuclear war as a tactic and open war would have caused the complete destruction of both nations.19 The United States specifically used public diplomacy on people from neutral nations and allies in order gain support for their cause.18 The cold war ended in 1991 and it took both communist countries and the United States a few years to release their archives.6 A few books published on the public diplomacy of the cold war was published in the early 2000s by diplomatic historians. An increase in interest of propaganda and how it influenced history happened right after 9/11.15 The new ways for the public to receive information and news gave more power to organizations and people outside of governments, making the need to study propaganda and its influence on other nations more important.15 The USC center for Public Diplomacy, founded in 2003, is currently the leading pioneer in public diplomacy and became the world’s first college to offer a master’s degree in public diplomacy in 2005.21

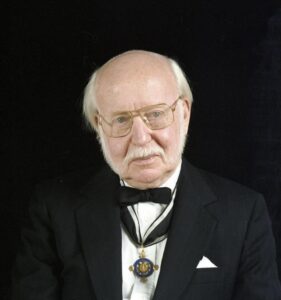

Nicholas J. Cull

Nicolas J. Cull is the leading historian and pioneer in the study of diplomatic history.21 He is currently a professor at the University of Southern California at the Center on Public Diplomacy.21 He was the founding director of the master’s program in Public Diplomacy.21 Cull published eight books including his first, “Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign Against American “Neutrality” in World War II”.21 Cull embodies the principles of a diplomatic historian and a public diplomacy historian. His work “The Cold War and the United States Information Agency” is a great example of a Public Diplomatic history. According to Emily Rosenburg, “Cull presents the first comprehensive history and assessment of the varied elements that comprised the USIA’s mission to tell ‘America’s story to the world’.”25 He uses a more traditional diplomatics method by looking at declassified archives and he interviewed over 100 people who were involved in the public diplomacy programs.26 He also used a newer public diplomacy lens for his interpretation, he asked questions about journalistic truth and the struggle between politicians and a state run international radio station.26 27

Works Cited

2 Ruey, Tethloach. “History.” Diplomatic World Institute , February 28, 2023. https://www.diplomatic-world-institute.com/en/history/#:~:text=The word ‘diplomacy’ originated from,together in a particular manner.

3 “Empiricism, Gender and History and Postcolonial Perspectives.” Essay. In Houses of History, 1–277. New York: New York State Radio Bureau, 1948.

4Ranke, Leopold. “The Theory and Practice of History Pg.xix.” Edited by Georg Iggers. Google Books. Google, 1973. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GjRZBwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=leopold+von+ranke+vetitian+archives&ots=4dW9aS_lBf&sig=CJ7bSoxKg90HtHpQ9GdaCAqUaYo#v=snippet&q=diplomatic&f=false.

5 Mulligan, William. Essay. In The Primacy of Foreign Policy in British History, 1660-2000: How Strategic Concerns Shaped Modern Britain, 121–21. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

6 Finney, Patrick. “International History.” International History – Articles – Making History, 2008. https://archives.history.ac.uk/makinghistory/resources/articles/international_history.html#2.

8 “Causes and Effects of World War I.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/summary/Causes-and-Effects-of-World-War-I.

9Ehrhardt, Andrew. “A ‘Great Power’ Man or World Stater? the International Thought of Charles Kingsley Webster, 1886–1961: Modern Intellectual History.” Cambridge Core. Cambridge University Press, April 26, 2023. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/modern-intellectual-history/article/abs/great-power-man-or-world-stater-the-international-thought-of-charles-kingsley-webster-18861961/CF24B074487FA6C5375E95C7DF2475F0.

10“Charles Kingsley Webster: News: The Harvard Crimson.” News | The Harvard Crimson. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1932/3/26/charles-kingsley-webster-pthe-calling-of/.

11 Hall, Ian. “The Art and Practice of a Diplomatic Historian: Sir Charles Webster …” Research Gate. Accessed May 6, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248876334_The_Art_and_Practice_of_a_Diplomatic_Historian_Sir_Charles_Webster_1886-1961.

12 Fry, Micheal, and Andrew Williams. “DIPLOMATIC, INTERNATIONAL AND GLOBAL -WORLD HISTORY.” International relations, n.d. http://www.eolss.net/sample-chapters/c14/e1-35-01-04.pdf.

13 “Gordon A. Craig: AHA.” Gordon A. Craig | AHA. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/presidential-addresses/gordon-a-craig.

14 “New Diplomatic History.” Humanities and Social Sciences Online. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://networks.h-net.org/tags/new-diplomatic-history.

15 https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/page/what-is-pd#:~:text=As%20coined%20in%20the%20mid,which%20had%20acquired%20pejorative%20connotations.

16 “Public Diplomacy.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/public-diplomacy.

17 Cull, Nicholas. “‘Public Diplomacy’ before Gullion: The Evolution of a Phrase.” USC Center on Public Diplomacy, November 4, 2016. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-diplomacy-gullion-evolution-phrase.

18 “Propaganda – Cold War.” Encyclopedia of the New American Nation. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.americanforeignrelations.com/O-W/Propaganda-Cold-war.html.

19 https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-10433-8_9

20 authors, All, Helmer Helmers ‘Transnational Publicity in Early Modern Europe.’ “Public Diplomacy in Early Modern Europe.” Taylor & Francis. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13688804.2016.1174570.

21“History and Mission.” USC Center on Public Diplomacy, September 25, 2018. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/page/history-and-mission.

22 “NICHOLAS_CULL.” USC Center on Public Diplomacy. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/users/nicholas_cull.

23“Diplomatic History and Colin Elman and – Jstor Home.” Accessed May 6, 2023. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539324.

24 “Call for Papers: Reframing Diplomacy: New Diplomatic History in the Benelux and Beyond.” Call for Papers: Reframing Diplomacy: New Diplomatic History in the Benelux and Beyond | Historici.nl. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.historici.nl/call-for-papers-reframing-diplomacy-new-diplomatic-history-in-the-benelux-and-beyond/?type=call+for+papers.

25 “CPD University Fellow Nick Cull Pens New Book on Cold War Public Diplomacy.” USC Center on Public Diplomacy, November 5, 2016. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/story/cpd-university-fellow-nick-cull-pens-new-book-cold-war-public-diplomacy.

26Gregory, Bruce. “The Cold War and the United States Information … – Naval War College.” The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 2009. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1783&context=nwc-review.

27 “History of VOA.” VOA. Accessed May 6, 2023. https://www.insidevoa.com/p/5829.html#:~:text=The%20Voice%20of%20America%20(VOA,media%2C%20radio%2C%20and%20television.

Images Cited (In order)

Photograph. 2013. Call for Papers: Reframing Diplomacy: New Diplomatic History in the Benelux and Beyond. https://www.historici.nl/call-for-papers-reframing-diplomacy-new-diplomatic-history-in-the-benelux-and-beyond/?type=call%20for%20papers.

Photograph. n.d. IWM. Imperial War Museum . https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205331698.

Prof. Dr. Gordon Craig Historiker. May 27, 1991. Photograph. Gordan A Craig. German Federal Archive . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gordon_A._Craig.

Nicholas Cull. n.d. Photograph. Nicholas Cull- Press Room USC. https://pressroom.usc.edu/nicholas-cull/.