Historical Laboratory Projects

Gender History- Hurt

Gender History is a field that focuses on the roles that gender has played in shaping and forming history. It started with the growth in the seventies due to the woman’s history movement which focused on their impact on history. It then expanded to encompass gender, with the many influences that play with that, such as cultural and community ideas and practices. The main ideas of gender history are that history is shaped by the influences that genders have had on influencing what has happened in the past and how that has influenced the present. This idea pushes the notation that history was just male-dominated. With the fact that history as a subject focuses mostly on male figures and their contribution to history overlooking the influence that women have had on these male figures. Female figures are often linked to male prominent figures never by themselves. An example of this could be Mark Anthony and Cleopatra. Cleopatra is often spoken about in terms of her relationship with Mark Anthony and the outcomes this relationship caused.

A historian that help push this house forward and was also a prominent face of this house was Gerda Lerner. In the field of women’s and gender history, Gerda Lerner made significant contributions as an Austrian-American historian and scholar. In 1920, she was born in Vienna, Austria, and passed away in Madison, Wisconsin, on January 2, 2013. In 1966, Lerner graduated from Columbia University with a Ph.D. in history, focusing on women’s suffrage in Austria. As a founding member of Sarah Lawrence College’s first graduate program in women’s history, she played a key role in the development of the field of women’s history. Her other accomplishments include serving as president of the Organization of American Historians between 1980 and 1981, making her the first woman to hold such a position. In addition to focusing on women’s experiences and how they intersect with race, class, and sexuality, Lerner made significant contributions to gender history. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of history, examining the lives of marginalized women, including women of color and working-class women is essential. The field of women’s and gender history has been greatly enhanced by Gerda Lerner’s contributions. Her scholarship and activism have inspired countless scholars and activists to continue to work toward a more inclusive and equitable understanding of history.

Gender History has a very muddled history in terms of when this house emerged. Gender history is made up of many subsets that focused on different topics. These topics could be women, men, and LGBTQ. Each subset has been brought to the forefront in varying times and years. With their re-emergence in the amount of attention, they have been given. Woman’s history started in the 1970s with the start of the feminist wave which led to many starting to shift their focus to the woman’s perspective. LGBTQ history could be argued that it started in the early 21st century though it can be said that there has always been a push to bring the LGBTQ experience and history to the forefront. When it comes to men’s history, the bulk of history has been focused on men. So, there can’t be a start to men’s history when there has been a focus on it.

An example of gender history is the many studies on Africa and the influences that the transatlantic Slave trade had on African communities and ideology. One such historian that is under the House of Gender History is Jennifer L. Morgan. She is a professor of history at the University of New York and a part of the Department of Social and Cultural Analysis. She focuses on the history of the Black Atlantic World, Comparative Slavery, and Gender sexuality studies. She has a lot of work that focuses on how gender and the transatlantic slave trade were tied together and influenced each other. She also focuses on how this left long-term effects on present-day African Americans and Africans in countries that were a part of the slave trade. One of her books includes Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic.

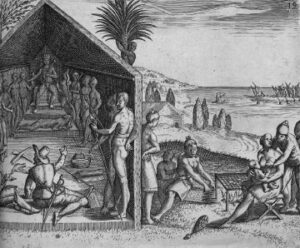

Using the lived experiences of enslaved African women of the 16th and 17th centuries, Reckoning with Slavery examines the contours of early modern notions of trade, race, and commodification in the Black Atlantic. In the Middle Passage, women were demographically counted as commodities from their capture to their transport, sale, and childbirth. They were vulnerable to rape, separated from their kin at slave markets, and subject to laws that enslaved their children at birth. By doing so, they played a key role in the tying together of reproductive labor, racial hierarchy, and the economics of slavery. According to Morgan, Western notions of value and race developed simultaneously throughout this comprehensive study. She explains how slavery perpetuates and enforces slavery by exploiting enslaved women’s bodies, denying them kinship and affective connections.

When you expand on this topic of women in the transatlantic slave trade you would be able to see the effects that the Western world and Africa played in the trade. Africa before the slave trade had their ideas and understanding of gender. The understanding greatly influenced the slave trade and which gender was being traded. When the beginning of the slave trade happened many of the slaves being shipped off to the Western world were men. The thought behind this was that men would be able to better work the plantations and would have a higher value in the market. This thought by the Western world was not held by Africa. Women were the more favored in the trade. Women at the time had a very high work rate making them more profitable. Though with the difference of importance, they but on what gender the Western world and Africa favored the price difference between both genders was lower. “Women could be sold for more in domestic African slave markets, whereas men commanded higher prices in markets supplying the Atlantic. Women thus constituted the large majority of slaves in Africa.”[1] This is because males were seen as more of a function of supplies rather than them being in demand. Whereas women and children were channeled away from the Atlantic and inland.

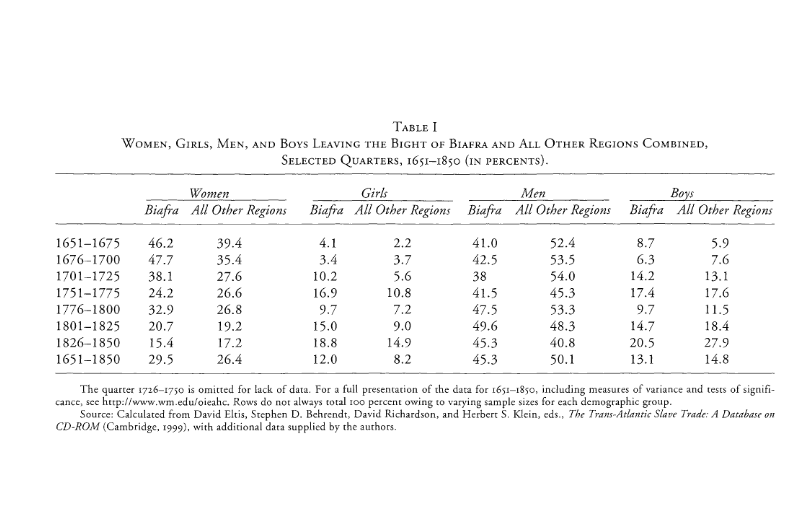

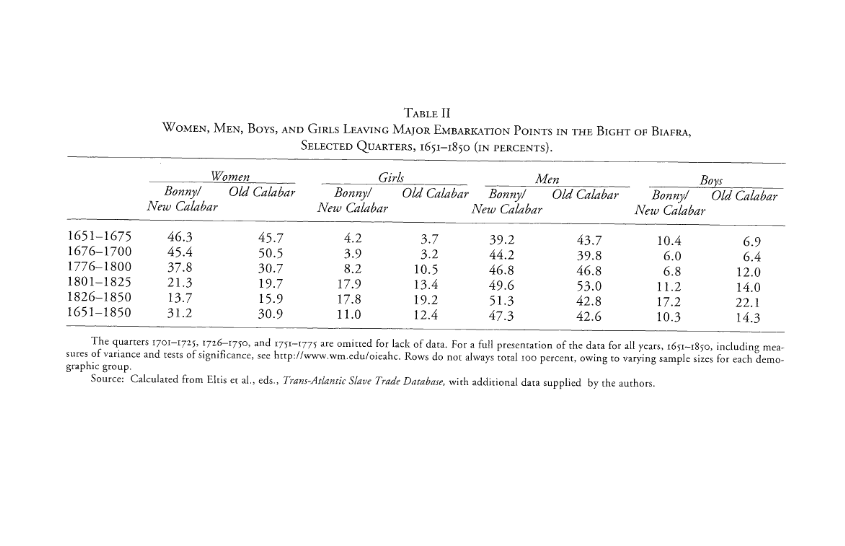

Africa had a very strong and high value placed on women, which was a great factor in the slave trade. Women had a higher value inland while men had a higher value on the coast where the trade was happening. There were only a few cases where women were in high demand near the coast. These places were known as provenance areas. “Women and children were important in overseas markets only where the major provenance areas were the coast.” [2] One such place was the Bight of Biafra which had more women enter the slave trade than any other coastal region. This effect can be contributed to the impact that American and European buyers had. Male slaves were available in neighboring regions where the price for them was higher. While in the Blight of Biafra, women were sold at a much lower rate. So, these American and European buyers were able could down the price and were now even more open to the purchase of more female slaves. So, in comparison to other coastal ports the Blight of Biafra sold more women, but the number compared to its data of sales in this region men were still sold more than women.

This information led to one conclusion about the effects of the slave trade on African conceptions of gender. Africa saw slavery as a way to maximize profit which greatly affected gender views and ideas of gender. In Africa, three different markets funded the trade with African slaves. Those three are the Atlantic, Saharan, and domestic markets. “In general, the Saharan market was female-oriented, whereas both females and children predominated in the domestic market. The Atlantic market concentrated on dealing in males, preferably adult males.” [3] These three markets greatly influenced each in terms of what was sold and what prices they charged. Especially which gender would be sold with that said each market from the three major regions also had its own distinct and special identity.

One specific region that we can look at that showcases the role gender had on the slave trade is the Blight of Biafra. In this region, African warfare and the role of women was very intertwined in the indigenous economy and social institutions. This influence very much pushed the age and gender that would structure the slave trade. The region because of this influence was set apart from the other slave markets. The main reasons why that influenced this market are the ideas of division of labor, reproduction in the context of lineage, polygyny, and the methods of enslavement.

When you move this lens and look at slavery’s effects in colonial America you would be able to see some differences and similarities. As stated, before when the slave trade first started the gender that was dominantly sent to the colonies was males. While in the colonies the men would be subject to several tasks that were physically demanding which harkens back to the fact that Europeans would buy men because they would bring more profit. “Considered more valuable workers because of their strength, enslaved men performed labors that ranged from building houses to plowing fields.” [4] When you look at females in colonial America they were brought over mostly as the company for the male slaves or because of the low selling price they were purchased for. “Early on, slave buyers in the colonies turned to purchase female field hands, who were not only more readily available but also cheaper.” [5] A woman would be put to work in fields because most of the jobs that had to do with skilled labor would be given to men leaving open positions for women to take up in the fields.

In the colonies, slaves often experienced a sense of unknowing about their traditional identities and understandings of gender that they had carried with them from Africa. The first example of this is tied to the work that women did on fields and plantations called hoeing. On fields in South Carolina men and women would hoe the fields together.“The task was emasculating, given that the hoe was specifically identified with women’s work in West Africa.”[6] The duty of hoeing and cooking the food was traditionally a woman’s domestic work. The second example is tied to pregnancy and childbirth which was an especially important tradition for African women.

In Africa, childbirth was considered a rite of passage that would increase and help them gain respect. But life in the colonies used childbirth and pregnancy as a means to increase profit through reproduction and increase the labor force. Childbirth was encouraged by owners and often forced on women. “The average enslaved woman at this time gave birth to her first child at nineteen years old, and thereafter, bore one child every two and a half years.”[7] This cycle came with both benefits and burdens to the female slave. The benefits are that when the female is pregnant, they are often given more food and water ad were expected to work fewer hours. They were given these benefits because the owners prioritized the fertility of the woman and the good health of the baby. Some burdens that the mother would face are seen both physically and mentally. Physically after giving birth, they would soon go back to the fields and continue to work. Mentally they would not be able to make a motherly connection with their child. On bigger plantations, the child would be taken from them and raised by another. Unlike large plantations mothers on smaller fields would be able to raise their children but the duty of raising the child would have to be added to the responsibilities they already had.

While both the female and male gender both experienced uncertainty about their gender roles in the colony female slaves also experienced exploitation sexually which male slaves did not. Female African slaves were seen as lustful beings by the colonists in contrast to an ideal nineteenth-century white woman. “Because the ideal white woman was pure and, in the nineteenth century, modest to the degree of prudishness, the perception of the African woman as hyper-sexual made her both the object of white man’s abhorrence and his fantasy.”[8] So, this idea coupled with the fact that these African women were in bondage led many men to believe it was their right to take advantage of the slave in sexual ways. Female slaves were often raped and taken advantage of by their owners and had no say in their treatment.

So, when you take into account the contrast in treatment of the slave man and woman this can be transferred to the ideas of what they thought of obtaining freedom. The slave man would look towards escape as the best way to gain freedom as well preserve their masculine identity and induvial humanity. The female slave would look to deal with the fact they were not just an African slave but also a female. They had children to take care of and think about not just their personal goals. Since they had so much to think about, they often looked towards what they could do internally on the fields. They would use the desire colonist men had for them to their advantage and help lift their status within the fields. “Sometimes, female slaves acquiesced to advances hoping that such relationships would increase the chances that they or their children would be liberated by the master.” [9] These situations did not always play to their advantage but for those that did it did help their situation and give them far more opportunities than most.

In conclusion, the slave trade had a noticeably big implication on gender and the roles females and males had in colonial America and Africa. In Africa, there was more importance on where females were sold as they had bigger importance culturally to African society. Males were sold on the coast where they were more accessible while females were sold internally through Africa or more inland locations further from the coast. In the colonies, gender roles were not important in plantations and field society. Both males and females would partake in the same work as stated. They would both hoe the fields which traditionally in African culture was a female’s work. In the colonies, females had to deal with both enslavement as well as sexual exploitation. Females unlike males had to experience a high rate of fetishization by their owners. They were pushed or often forced into having pregnancies very frequently. Slavery’s historical legacy has had a profound and lasting impact on gender ideas and gender roles in both America and Africa.

[1] Nwokeji, G. Ugo. “African Conceptions of Gender and the Slave Traffic.” The William and Mary Quarterly 58, no. 1 (2001): 47–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/2674418.

[2] Nwokeji, G. Ugo. “African Conceptions of Gender and the Slave Traffic.” The William and Mary Quarterly 58, no. 1 (2001): 47–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/2674418.

[3] Nwokeji, G. Ugo. “African Conceptions of Gender and the Slave Traffic.” The William and Mary Quarterly 58, no. 1 (2001): 47–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/2674418.

[4] “Slavery and the Making of America. the Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender: PBS.” Slavery and the Making of America. The Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender | PBS. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/gender/history2.html.

[5] “Slavery and the Making of America. the Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender: PBS.” Slavery and the Making of America. The Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender | PBS. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/gender/history2.html.

[6] “Slavery and the Making of America. the Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender: PBS.” Slavery and the Making of America. The Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender | PBS. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/gender/history2.html.

[7] “Slavery and the Making of America. the Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender: PBS.” Slavery and the Making of America. The Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender | PBS. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/gender/history2.html.

[8] “Slavery and the Making of America. the Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender: PBS.” Slavery and the Making of America. The Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender | PBS. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/gender/history2.html.

[9] “Slavery and the Making of America. the Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender: PBS.” Slavery and the Making of America. The Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender | PBS. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/gender/history2.html.