Historical Laboratory Projects

The History of Gender and Sexuality in the Holocaust by Sue Mueller

The House of Gender & Sexuality

“Houses” or “Schools” are terms scholars use to refer to groups of historians who share a particular set of methodologies. The concept was introduced in the 19th century in response to new ideas and methodologies for studying history emerged. For instance, the “Annales School,” founded by French historians, emphasized the importance of long-term historical trends that shaped history using geography, economics, and social structures. This school of thought challenged the traditional focus on political events and individuals and emphasized the importance of studying broader social and economic processes.

Many historical “houses” or “schools” have emerged over time, each with ideas and approaches to studying history. These houses or schools are only sometimes mutually exclusive, and historians may draw on ideas from multiple schools or reject the concepts of schools entirely. However, the concept of historical schools or houses remains a valuable tool for understanding historians’ different approaches to studying the past.

Origin & Methodology:

During the 1980s, gender history emerged from women’s history as scholars who had expertise in studying women began to examine how systems of sexual differentiation impacted both women and men. They argued that gender was a relevant category of analysis for all historical developments, not just those related to women or the family. As a result, gender became a central focus in historical studies, while women’s history continued as a separate field. This approach also provided a new method of analysis for diverse topics. Gender historians have explored various subjects in global history, including women’s rights movements, LGBTQ+ rights, migration, colonialism, imperialism, and the diversity of gender and sexuality worldwide.

Historical Context:

Women’s history has only recently begun to be integrated into social history. In the effort to reclaim women’s agency, reclaiming their agency has often been relegated to the sidelines or overlooked in historical narrative. Even radical young historians of the 1960s and 1970s worked under the assumption that women were not active participants in history but relatively passive and politically inactive, existing to support men. Although there were occasional movements like suffrage, women were not seen as driving forces of change.

The contributions in gay and lesbian history since the 1980s have challenged preconceived notions of sexual and social identities. Before George Chauncey’s Gay New York in 1994, the common belief held that the lives of gay men were shrouded in shame and secrecy; not until after the watershed event of the Stonewall Riots in 1969 that the collective expressions of defiance and pride and individual coming-outs that coalesced cultural history and the homosexual world. Furthermore, Chauncey’s research proved that the homosexual world of New York was more intricate and intertwined with the straight world between the 1890s and 1930s than previously thought. “Chauncey’s research uncovered a complex landscape of identities – “faeries,” “pansies,” “sissys,” “nances,” “gays,” “trade,” “faggots,” “queers” – at odds with any simple binary of hetero – and homo-sexuality. The term “coming out” was an explicitly campy reference to the tradition of upper-class female debutante balls.”[1] The term’s origin, as Chuancy incisively remarks, is revealing: gay people in the 1920s and 1930s did not imagine themselves coming out of a closet but into homosexual society.

Gender & Sexuality in the Holocaust

The Legacy of the Holocaust is the extermination of millions based on race, religion, political belief, and other identities. Persecution of individuals based on gender and sexuality is neglected, omitted, or lost in the discussion and study of the Holocaust. Gender and sexuality are aspects of human identity that shape individual experiences. Under Nazi rule, the persecution of perceived gender and sexual identity resulted in human rights violations and mass extermination. The significance of studying gender and sexuality in the Holocaust is in highlighting the intersectionality of oppression and gender and sexuality. Examining gender and sexuality in the Holocaust elucidates the experiences of LGBTQ individuals which includes their persecution, resistance, and survival.

Origin and Methodology of Gender & Sexuality in the Holocaust

The study of gender and sexuality explores how gender and sexuality intersect with social identity and impacts an individual’s experiences during Holocaust, shaping social structures. It is the focus of the study of gender and sexuality during the Holocaust. Understanding how identity influences individual and social experience is the aim. This methodology of gender and sexuality studies of the Holocaust allows for a holistic understanding of events during the Holocaust while highlighting the experiences of those targeted by Nazis.

Persecution of LGBTQ Individuals in Holocaust

The opposition to homosexuality in the Nazi movement stemmed from overlapping prejudices. A notion propagated long before the Nazis rose to power is the pervasive myth of the belief that homosexuals were pedophiles. In 1928, socialist students at a Berlin high school invited Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, a renowned sexologist, to speak about student self-government and the rise in student suicides. Magnus Hirschfeld, the ‘pioneer’ for the repeal of Paragraph 175, was permitted to speak in German high schools. The Nazi Party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, instead focused on Hirschfeld’s sexuality instead of his speech, publishing a headline that read: “Homosexuals as Lecturers in Boys’ Schools. The destruction of German youth! German mothers, working women! Do you want to put your children into the hands of homosexuals?”[2] Employed in the mid-1930s this tactic was used against the Catholic Church, resulting in numerous show trials against monks and priests accused of sexually abusing boys in their care. Although some of the charges may have had merit, the sheer volume of trials – over 250 in 1936-37 alone – raised doubts about their validity in public. Even Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels acknowledged that many accusations were baseless, commenting, “When Himmler wants to get rid of someone, he just throws Paragraph 175 at him.”[3]Nevertheless, the propaganda machine persisted until it became clear that it was backfiring.

Experiences of LGBTQ in concentration camps

Explicitly targeting Jews, Roma and Sinti (Gypsies) as alien races, the German government in October 1935 enacted the Law for the Protection of the Hereditary Health of the German People. Further marginalized were the Roma and Sinti because of their perceived compulsion to wander. Robert Ritter, a psychiatrist who headed Himmler’s Reich Central Office for the Fight against the Gypsy Nuisance starting in 1936, began classifying the Gypsies. In September 1939, the “relocation” of the Gypsies began. In 1940, Ritter reported that 90% of “native Gypsies” had mixed blood and recommended concentration camp incarceration for 21,498 of the 30,000 Gypsies. Following their deportation to Auschwitz in February 1943, 20,078 out of approximately 23,000 perished at Birkenau.

In 1936, Himmler established the Reich Central Office for Combating Abortion and Homosexuality to ensure population growth. The expanded Paragraph 175 led to the arrest of about 50,000 (mostly male) homosexuals, with 10,000-15,000 sent to concentration camps. Many remained incarcerated or perished, and German states did not recognize them as Nazi victims until long after the war. In December 1937, Himmler issued a crime-prevention decree that targeted “asocials,”[4] a Nazi term for people who did not conform to social norms, and swept vagrants into concentration camps. The Interior Ministry classified asocials as community aliens “by virtue of a hereditarily determined and therefore irremediable attitude of mind”[5] in July 1940.

Statistics on LGBTQ individuals in the Holocaust

Approximately 100,000 men were apprehended between 1937 and 1939 for engaging in homosexual activity. Confined to concentration camps were 5,000 to 15,000 men. Ruediger Lautmann, a notable scholar on the Holocaust, estimates that the mortality rate may have reached 60%. Numerous survivors have attested that those who wore the pink triangle were subjected to severe abuse by guards and fellow prisoners due to prevailing biases against homosexuality. Many suffered physical and sexual abuse.

Persecution of homosexuals intensified after the outbreak of the war. From 1942, judges and SS officials in the camps were authorized to carry out forced castrations of homosexuals. Furthermore, in 1943, homosexuals were among the prisoners killed in an SS-sponsored “extermination through work” initiative, part of the final solution, in the concentration camps.

Stories of Survival

Stories of survival from LGBTQ victims are missing from the collective memory of Holocaust Remembrance. The end of Nazi oppression in 1945 did not bring queer liberation survivors. It marked the beginning of the systematic persecution and suppression. The subsequent persecution would result in the erasing of LGBTQ individual stories and history. Gay Holocaust survivors, after liberation, did not leave their camps being recognized as victims. Instead, they left as convicted criminals. Between 1945 and 1969, some LGBTQ survivors were forced to carry out their sentences in prison. East Germany had softer penalties for gay survivors; However, no reparations were made for gay victims of the Holocaust. It was not until 1994, after Germany’s reunification, was Paragraph 175 removed from the penal code.

The number of gay men murdered in the concentration camps is unknown. The number of men in the army who were executed for homosexuality is unknown. The number of Jewish is unknown. Men who were homosexuals and sent to the gas chambers are also unknown. It is impossible to know how many men took their own lives rather than be arrested as homosexuals. The exact numbers are not the point. What is crucial is remembering that thousands of men died because of their sexuality. Their stories are lost forever.

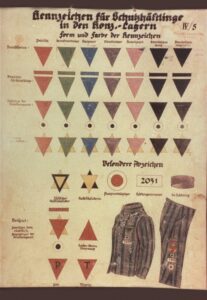

Pink Triangle

The Nazis destroyed Germany’s vibrant queer community and, as previously mentioned, arrested over 100,000 LGBT Germans. The color-coded badge system implemented by the concentration camp administration labeled the alleged crime of each inmate. “Queer women were labeled with a black triangle, the mark for “social deviants.” Queer men sent to concentration camps under Paragraph 175, Germany’s national law criminalizing “indecency between men,” were marked with a pink triangle.”[6]

Bibliography:

Burleigh, Michael, and Wolfgang Wippermann. The Racial State: Germany, 1933-1945. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Friedman, Jonathan C. The Routledge History of the Holocaust. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2011.

“Gender, Sexuality, and the Holocaust.” United States holocaust memorial museum. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://perspectives.ushmm.org/collection/gender-sexuality-and-the-holocaust.

Maza, Sarah C. Thinking about History. Chicago, Il: The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Newsome, W. Jake. “Coming to Terms with the ‘Gay Holocaust’.” The Gay & Lesbian Review, January 1, 2023. https://glreview.org/article/coming-to-terms-with-the-gay-holocaust/.

Newsome, W. Jake. Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming out in the Shadow of the Holocaust. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2022.

Setterington, Ken, Carolyn Jackson, Malcolm Lester, and Jonathan Schmidt. Branded by the Pink Triangle. Toronto, Canada: CNIB, 2014.

[1] Sarah C. Maza, Thinking about History (Chicago, Il: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 42.

[2] 1. Jonathan C. Friedman, The Routledge History of the Holocaust (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2011), 389.

[3] Friedman, 389.

[4] Michael Burleigh and Wolfgang Wippermann, The Racial State: Germany, 1933-1945 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 22.

[5] Friedman, 50.

[6] W. Jake Newsome, “Coming to Terms with the ‘Gay Holocaust’,” The Gay & Lesbian Review, January 1, 2023, https://glreview.org/article/coming-to-terms-with-the-gay-holocaust/.