“In this she must judge for herself”: Gretna Green and Women’s Choice / Sellman

“In this she must judge for herself”: Gretna Green and Women’s Choice / Sellman

We are living through a politically tense time – questioning the extent to which the government should be able to control people’s lives is a huge issue – and it is important to remember that people in the past had similar experiences. After the passage of the Marriage Act of 1753, lovers began eloping to Gretna Green just across the border in Scotland, then returning to England where the marriage was still lawful. This small town became an accidental space of protest where couples, and especially women, were able to exercise their agency, going against the wishes of family, friends, and the law.

By the time more moderate marriage laws passed in the nineteenth century, Gretna Green had become enshrined in England and the wider world’s culture. It is found in numerous popular culture works we consume today, including Pride and Prejudice and Downton Abbey.

Separate from its historical and pop culture significance, Gretna Green became a topic of discussion once again in 2022, when Scotland’s parliament was blocked by the UK from legislating a Gender Recognition Reform Bill that would have made it easier to change gender in Scotland, potentially creating a “transgender Gretna Green” as trans people from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland traveled to Scotland.

Table of Contents

- Historiography

- The Catalyst: The Marriage Act of 1753

- Marriage: the “Manufactory for making Children”

- Eloping to Gretna Green: “she thus decidedly shewed her preference”

- Gretna Green on Stage

- Gretna Green in Our Time

- Popular Culture: Pride and Prejudice and Downton Abbey

- “Transgender Gretna Green”

- The Future

Creator Bibliography

Aidan Sellman is an undergraduate student at Cleveland State University in her senior year. She is studying history and is interested in late medieval and early to late modern history in Europe and North America. After graduating she plans to get her Master’s of Library and Information Science degree to work in an archive or special collection (and possibly pursue a history MA).

Historiography

There is little scholarship that directly addresses the history of Gretna Green as a place to conduct clandestine marriages, so I have used a variety of secondary sources to supplement my primary source research.

Eve Tavor Bannet’s article The Marriage Act of 1753: “A Most Cruel Law for the Fair Sex” explores the reasoning for and implications of the Marriage Act of 1753. Bannet writes that the Act’s importance has been ignored by historians because they accepted the reasoning for the Act put forth by the man who presented it: that the Act was only meant to prevent wealthy heirs, and especially heiresses, under the age of majority from marrying without consent. Bannet argues that this is incorrect; the Act affected everyone, rich and poor, and ample evidence of this is found in the writings of women from this time. Bannet is a professor at the University of Oklahoma and specializes in the eighteenth century, British and American literature, and gender history.

Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall’s book Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850 had a massive impact on the field of gender and women’s history, being one of the first books of its type published. Davidoff and Hall explore the development of England’s middle class by focusing on the city of Birmingham and the rural counties of Essex and Suffolk. It argues that women had an essential contribution to family businesses and the development of England’s capitalist economy. Davidoff was a historian of sociology, specializing in social history, gender studies, and women’s history. Hall specializes in gender history, colonial history and British history and is emerita professor of British social and cultural history and chair of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery at University College London.

Kimberly Schutte’s chapter “Elopement and Defiant Matches: Marrying Outside the Bounds of Propriety” from her book Women, Rank, and Marriage in the British Aristocracy, 1485-2000: An Open Elite? examines the clandestine marriages of aristocratic women using primary sources. It focuses on elite women’s agency in making marriage decisions for themselves within an oppressive society which disapproved of this behavior. Schutte is a professor at the University of Kansas and specializes in early modern European history and gender.

Lisa O’Connell’s chapter “Literary Marriage Plots: Burney, Austen and Gretna Green” in her book The Origins of the English Marriage Plot explains how Gretna Green influenced literature of the era, creating the “marriage plot” trope found in works by Frances Burney, Jane Austen, and others. O’Connell is an associate professor at the University of Queensland and specializes in eighteenth-century British literature.

The Catalyst: The Marriage Act of 1753

The Marriage Act of 1753, also known as the Clandestine Marriages Bill and Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act, was enshrined in English and Welsh law on March 25, 1754. It placed restrictions on couples that the Catholic Church and then the Church of England had been trying to enforce for centuries. Under the new Act, several steps had to be taken for a marriage to be legitimate: banns announcing the intended match had to be read in Church three Sundays in a row; a marriage license had to be acquired; the marriage itself needed to be performed in a Church of England by an authorized clergyman; witnesses were required; the marriage had to be recorded in a marriage register; and permission from parents or guardians was required if either the bride or groom were under twenty-one years, the age of majority. Only Quakers and Jews were exempt.[1]

For centuries, women and men had been able to conduct a marriage by simply agreeing that they were now married, without witnesses, church, or permission. There were a few ways to do this, as Bannet explains: “if expressed in words of the present tense…the couple’s promise to live together as man and wife created a binding marriage” which did not require consummation or witnesses. Alternatively, “if the couple’s promises were expressed in words of the future tense…the marriage became binding as soon as consummation occurred.”[2] This often caused issues. For example, a woman and a man might agree that they were married, had sex resulting in a pregnancy, and the man then denied that any marriage had taken place. A person could potentially marry dozens of people without anyone knowing, committing bigamy. Despite the relatively few instances of this, it caused the Catholic and then the Protestant Church constant worry.

In spite of these problems, the average person valued their ability to marry without interference, believing that marriage was a “FAITH by which the Man and Woman bind themselves to each other to live as man and Wife.”[3] Those against the passage of the Marriage Act argued that the House of Commons was changing marriage, giving it “a different signification from what it had before.”[4] Couples who had privately married and never been publicly married in church were now considered to be living in sin and their children illegitimate. A woman who had sex and fell pregnant after promises of marriage could no longer find legal support.[5] The Marriage Act also made marriage a public business. Not only did the couple’s guardians have to be involved if they were underage, but whatever the age of the couple, the reading of the banns alerted the entire community to the impending marriage, making them involved whether they wished to be or not, and giving them plenty of notice to voice their opposition to the match.

There was an image in the popular imagination of a young woman being seduced and marrying a lower-class man who, under English common law, would possess all of her inherited money. This was true for the upper as well as the middle classes: “the desire to protect vulnerable property was integral to middle-class practice,” write Davidoff and Hall, “at the same time as the concept of female dependency was being elevated in political and social thought.”[6] The House of Commons argued that the Marriage Act was simply a way to prevent minors who stood to inherit their family’s wealth and property from marrying beneath their social station, when in actuality the Act was changing the fundamental nature of marriage as all parts of society, rich and poor, understood it.

Marriage: the “Manufactory for making Children”

The true intent behind the Marriage Act, founded on ideas in the new field of political economy, was to increase Great Britain’s population – but only the population that contributed to the wealth of the nation. Their labor benefited the wealthy, including the men in the Houses of Parliament. Arguing for the passage of the Act, the Earl of Hillsborough said that “the happiness and prosperity of a country does not depend on having a great number of children born, but on having always a great number well brought up and inured from their infancy to labour and industry.”[7] This was not necessarily wrong, but the average person was likely more concerned with having autonomy in their personal life and religious beliefs, not marrying to produce workers for the country.. As Hall and Davidoff write, “the crucial role of marriage in business affairs permeates the lives of the middle class in this period.”[8] The same was true of all classes, to varying degrees. Marriage was one of the most important economic decisions a person would make in their lifetime, particularly for women, who were expected to rely on their husbands’ financial abilities, and so having restrictions such as the Marriage Act suddenly placed on them must have been distressing.

Another of the key beliefs that drove the Marriage Act’s passing was the idea that children born from private marriages were less useful, either because their parents were destitute and not able to raise their children properly, or because a person seduced into marrying below their station would have children of a lower class than they otherwise would have. The government hoped that the Act would reduce premarital sex in women and men, for similar reasons: “the mother without the aid of the father is not at all sufficient” because of “the natural origin of the superior disgrace which attends a breach of chastity in women rather than in men.”[9] In a time before public welfare, Bannet writes, it was down to individual parishes and private charities to care for impoverished individuals and families. The children of single mothers “must necessarily fall for support on society or starve” and would not be useful to society.[10] With the passage of the act, the men in government hoped marriage would now be the “Manufactory for making Children” who increased the wealth of the nation rather than, supposedly, detracting from it.[11]

Eloping to Gretna Green: “she thus decidedly shewed her preference”

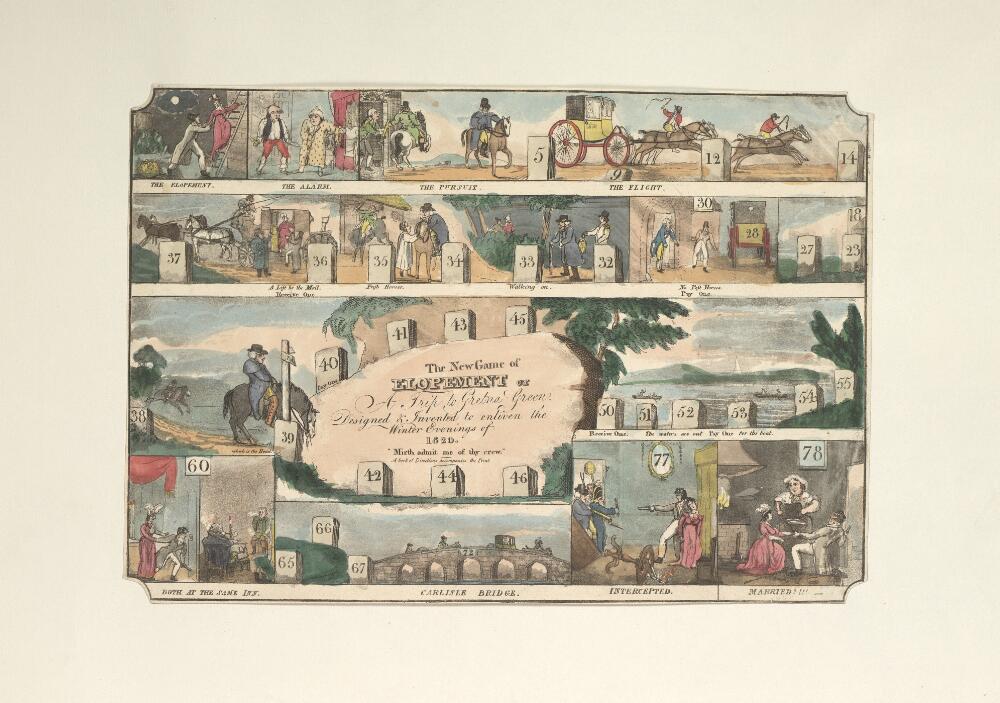

Though the Marriage Act had been enforced since 1754, it took until the turnpike network was extended to Gretna Green in 1770 for it to become easily accessible to England. Now, couples could “reach Gretna Green by coach within three days from London.”[12] In 1792, the Hereford Journal reported that seventeen-year-old Miss Midgley, the sister of Lady Grantley and the sister-in-law of Lord Grantley, an heiress with “not less than forty thousand pounds,” had eloped to Gretna Green, Scotland. After her brother-in-law had been considering making her a ward of the Court of Chancery, “she thus decidedly shewed her preference” by marrying Mr. B, “an American Gentleman,” in 1792.[13] “It is easy to dismiss the Gretna wedding,” O’Connell writes, “forgetting that it was a vehicle for powerful, often transgressive, social energies. It bypassed marriage markets, flouted courtship norms and reimagined the social meanings of marriage itself.” Instead of quietly agreeing to the new conditions of marriage imposed by the Marriage Act, couples found a physical way to circumvent them by traveling to Scotland to be married, where the Marriage Act did not apply, and the old rules were still in place.

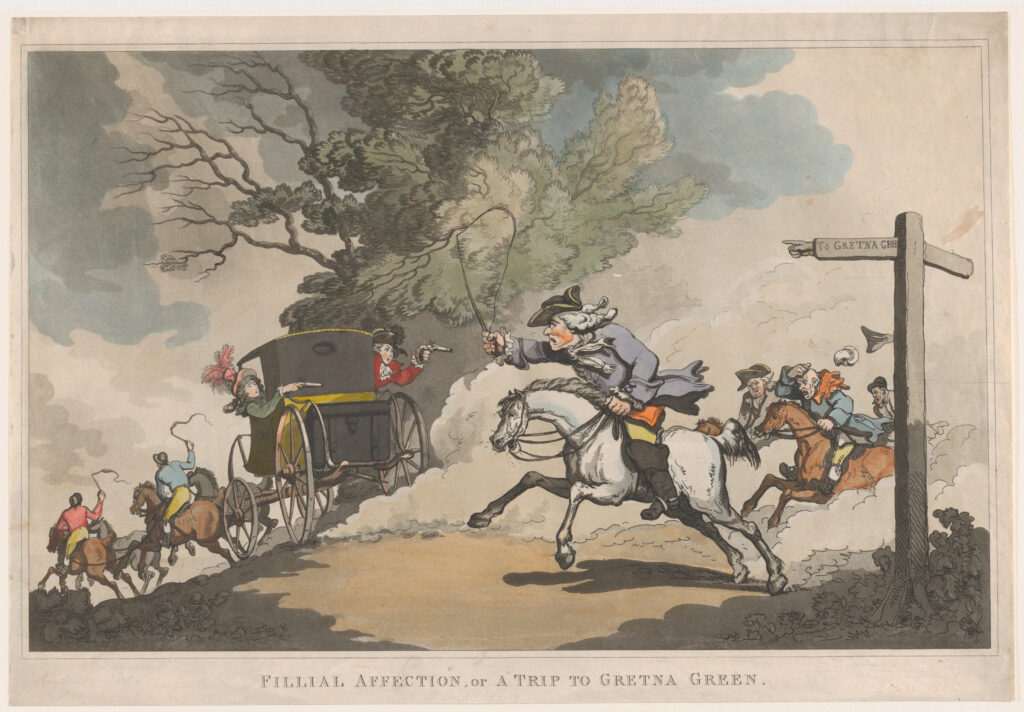

There were thousands of Scottish elopements beginning in the 1770s and lasting until 1856, when Parliament “imposed a three-week residency requirement on all marriages north of the border,” effectively ending these marriages.[14] There were also many thousands of articles about Gretna Green in contemporary newspapers, showing the keen interest that the public had in elopements. Indeed, “representations of them formed a staple of the popular media” which was “most interested in elite, under-aged couples” who went to Gretna Green to marry without parental permission.[15] Wealthy women likely faced a greater challenge in securing their choice of husband than did their middle- or working-class counterparts, as “it was difficult – though not impossible – for aristocratic women to exercise agency in the matter of their marriages,” because they were expected to make a match that benefitted their family’s social status and wealth.[16] Gretna Green “quickly became associated…with unlicensed female desire.”[17] Because of this, the figure of the bride is usually mentioned with far greater detail in newspaper articles than the groom, framed as victims of the seducing, fortune hunting man. Despite this, the sometimes humorous often surprisingly supportive language used to describe these women offers us a glimpse into their lives as they risked ridicule, potential destruction of their reputations, and even physical violence to make their own choices in life.

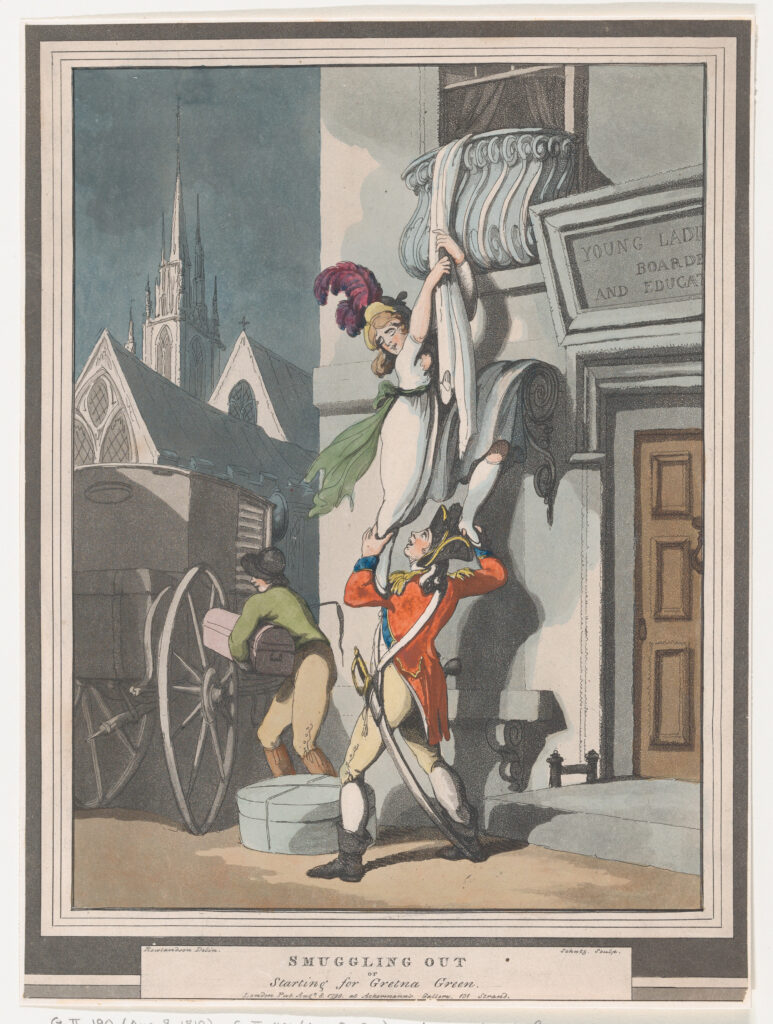

In 1786 a “young Lady, whose Age was scarcely 16” had “run off with her Mother’s Footman” and was successfully married, as “the Blacksmith of Gretna-Green had rivetted them together.”[18] In 1797, “Miss Taylor….and Mr. Hancock, set out a few days since for Gretna Green, on a visit to the love-combining Blacksmith, for the purpose of being riveted together on the matrimonial anvil.”[19] It is not clear when the figure of the Blacksmith Parson was first popularized, but by the 1770s he had become a part of the mythos of Gretna Green. Later in the early nineteenth century, some articles argued that he had never been a blacksmith at all but was instead a tobacconist. Whatever the truth, writers made constant reference to him. In 1777, an excerpt from A Journey to the Highlands of Scotland; with Occasional Remarks on Dr Johnston’s Tour: By a Lady was printed in the Caledonian Mercury:

“Nothing need be said of the road between England and this place, it being so universally known, since the legislature thought fit to form an act which hath rendered it so fully fashionable…to throw of the leading-strings of parental restraint. For, the glowing females of the present generation are not to be tied down by either prudish or prudential duties…but the most laughable circumstance is…that this kind physician of eloping lovers is by vocation a black-smith, who, on the sight of a chaise, throws down his hammer, and runs to the church.”[20]

The popularization of the Blacksmith at this time displays how the idea of Gretna Green had taken hold in the popular imagination, as it still is today.

The newspapers also did not shy away from hinting at physical attraction or premarital sex. Scotland’s marriage laws allowed anyone sixteen years or older to marry, provided a ceremonial consummation took place with two witnesses seeing the couple in bed together. The Derby Mercury wrote in 1783 that “Several laughable Circumstances often happen at Gretna Green, at this Conclusion of the Ceremony.” The elopement of a “an Irish Officer” and “a Lady from Northamptonshire” was one of these. When the parson explained that the bedding ceremony had to be performed before he could sign the marriage certificate, the Irish Officer “replied, ‘By my Faith, Parson, if that stops your signing, sign away, Honey, for that part of the Ceremony was over ere I reached York.’”[21] In February of 1802 the Chester Chronicle reported that “the road to Gretna Green is still passable, notwithstanding the immense fall of snow in that quarter. This is no doubt owing to the passengers, who are generally in a melting mood.”[22] Popular culture – in this case being transmitted via newspaper – seems to have often sided with the couples in their desire to marry, and not with the government which was trying to prevent these matches.

Apart from the couple and the parson, the other most frequent figures in the newspapers were the parents or guardians. In one particularly long article from 1794, the fathers of the couple were the noteworthy and entertaining subject: “You will not be displeased with the story of two old gentleman who, some short time ago, met at an inn on the North road…the one in pursuit of his son, and the other in pursuit of his daughter.” The gentlemen were both “equally averse” to their children marrying and argued, “each accusing the other of wanting that vigilance, or authority over his own child” that could have prevented the elopement. Despite this argument, they were forced to share the one available post-chaise to follow the couple. As the article wrote, “You may easily imagine what ‘agreeable companions’ they were…considerations of economy, however, and the opportunity of continuing their mutual reproaches, reconciled them to one carriage.” After they arrived at Longtown, the last stop before Gretna Green, needing to exchange horses, they found the last available post-chaise had been used by their children. After “recruiting their strength and spirits by recourse to the larder and a bottle of wine,” they realized the couple were now too far away to stop but by this time “the refreshment of food and wine had now somewhat cheered their hearts” and they “cooly discussed the circumstances of the case, and at last, shaking hands, concluded with a resolution of staying where they were to give their blessing to the happy pair on their return.”[23]

While many elopements were humorous affairs fueled by passion and love, others were done out of necessity to prevent an undesirable marriage. In 1777, Miss Brown, “not more than 18,” eloped with Mr. Bew, having “discovered a spirit and resolution on this occasion that does honour to her age and sex.” She was believed to have married Mr. Bew to “prevent a sacrifice of her charms…to an old gentleman, her guardian” who planned to marry her in a few days.[24] Only three years later in 1779, “early in the Morning” Miss Armystead “set off on a Matrimonial Expedition” to Gretna Green with Mr. Horseman.” She was seventeen, “possessed of a large independent Fortune,” and was determined to marry Mr. Horseman to “prevent a Sacrifice of her Charms to an Old Man of 70.” This “Old Man” and Miss Armystead’s father followed the couple, but it was expected that they would not “arrive in Time to prevent their intended Union.”[25] These two young women may have preferred not to marry at all, but when forced to decide they at the very least made their own choices, choosing a husband who was closer to them in age. Judging by the language used, the newspapers, and therefore society at large, agreed with this decision. Once again, the Marriage Act and government were being circumvented.

Countless women successfully made the trip to Gretna Green and returned home with their chosen husbands, but an unknown number were also stopped on the journey, often by their parents or guardians. In 1804, the Sun wrote of a “young Lady,” seventeen years old, with a “considerable fortune,” who had been corresponding for an unknown length of time with a “Gentleman to whom her father had a great aversion.” Apart from the trip itself, which could be hundreds of miles, the greatest difficulty was leaving without being noticed. Young women, especially wealthy ones, were monitored closely and chaperoned. In this case, the “young Lady” usually took a walk before dinner and used this as a cover story to meet with “the object of her affection,” after which they set off. At Kendal, about fifty miles from Gretna Green, the young lady’s father “on horseback…rode through the town by the side of the chaise” that the couple were in, “threatening them with punishment.” The young lady was eventually forced into a room where her father hit her with his walking stick twice. She told him that “she would very willingly comply with his wishes in any thing else, but in this she must judge for herself.” He refused and “she was obliged, very reluctantly, to return with her father.”[26]

In other cases, parents or guardians became aware of the couple’s intention to marry but were unable to stop them. The Newcastle Courant wrote in 1776 that an unnamed “Miss S—” with “an independent fortune of 1000 guineas” eloped with a young man “on a matrimonial jaunt to Gretna Green.” The young woman’s mother “was informed of the intention of the lovers, whom she immediately pursued on horseback” and after reaching them, “vented her fury on the young lady, not only by threats, but by cuffs, and a total demolition of her head dress.” Yet the couple were able to “slip out of the room,” lock the mother inside, and “rode off in triumph.”[27] Also in 1776, Miss Arnold and her suitor were determined to be married, despite the door of her “lodging-room” being locked every night by “the gentleman to whose care the lady had been intrusted, having some suspicions of her design.” But one morning he found “the bird had taken its flight” as Miss Arnold “by the assistance of her lover, and the aid of a ladder, had made a descent from the window.”[28]

Friends might also attempt to stop a couple from marrying. In 1807 a “young Lady” with a fortune of 400 pounds a year eloped with a young man who worked as a “domestic in the family.” The couple were “pursued by some friends of the Lady, who…surprised them at the Hoop Inn, Cambridge” but “no promises could induce the young Lady to return: she expressed her determination to marry the adventurous youth who had carried her off.”[29] Similarly, the Norfolk Chronicle wrote in 1780 that after Miss Atkinson and a schoolmaster, Mr. Elleton, set off for Gretna Green, the “friends of the young lady hired two men…to pursue them.” The couple had thought this might happen, however, and took back roads so that the hired men arrived before they did and left, thinking they had arrived too late. The men were then “informed at Carlisle, that a post-chaise…contained the objects of their intention.” After stopping at Long Town, the couple learned the men were nearby and sent the post-chaise without them as a decoy. The couple then “walked about fourteen miles to Eller-Cleugh, in Scotland, where they [were] quietly married.” Mr. Atkinson, the young lady’s father, was “now tolerably reconciled to the match” and planned to “give his daughter a very genteel fortune.” Though the marriage did not actually take place there in the end, the fact that Gretna Green was the intended destination and then became a decoy shows how important it had become as a place of elopement and, crucially, a place of protest against the government.[30]

The vast majority of elopements to Gretna Green which were reported on in newspapers ended in success for the couple. The Leeds Intelligencer wrote in July 1776 that at least nine people had been married at Gretna Green in the last week; a little less than a year later in May 1777 it reported that more than ten couples were married there in the last twelve days.[31] It is difficult to say whether elopements were usually successful or if newspapers were simply more likely to report on a successful one – if the latter, then this perhaps reflects on the public’s disapproval of the Marriage Act of 1753 and their championing of the women and men who dissented.

Gretna Green on Stage

As elopements to Gretna Green became part of the public consciousness, numerous stage productions involving it began to pop up; some were performed for many consecutive years. It appears that the first of these was performed at the Theatre-Royal, Hay-Market in 1783. The play, simply titled “Gretna Green,” was described as a “new Musical Farce, in Two Acts,” and included “Italian, French, Irish, Scotch, Welsh, and English music.”[32] O’Connell writes that the couple’s marriage “furthers Britain’s glorious cause” fighting against the Spanish at Gibraltar, “while also pressing the popular case against the English Marriage Act’s tyrannies.”[33]

Then in 1803, “The Scotch Lovers; Or, The Gretna Blacksmith” by M. Laurent was performed for the third time at “Theatre, Birmingham” in 1803. Described as a “Comic Dance,” it included “Strathspeys, Scotch Flings and Reels.”[34] Between 1810-1812, the “Caledonian Lovers; Or, The Gretna Blacksmith,” was performed at the Royal Theatre, Birmingham.[35] In 1813 the Threatre-Royal in Bath performed the “The Gretna Blacksmith,” a “Comic Ballet-Dance”; whether this was the same production as the “Scotch Lovers” and “Caledonian Lovers” or another play is not clear.[36] Plays such as these continued to be performed well into the 1800s.

Gretna Green in Our Time

The mythos of Gretna Green has continued into the twenty-first century. This is thanks to the enduring legacy of authors like Jane Austen, who used Gretna Green as a plot device in more than one of her novels – the most famous being Pride and Prejudice – and who may have read some of the newspaper articles included here. Modern works such as Downton Abbey utilize Gretna Green with the expectation that their audience will be familiar with it. Couples still go to Gretna Green to be married, albeit less scandalously. Most recently, the idea of a “transgender Gretna Green” as transgender people find Scotland’s gender affirming laws to be more welcoming than England’s, has become part of the discussion surrounding Scotland’s independence.

Popular Culture: Pride and Prejudice and Downton Abbey

By the end of the eighteenth century, “no trope signified modern consumer culture’s pleasures and dangers for women more powerfully than clandestine marriage.”[37] At the same time, Gretna Green marriages were useful literary plots, “not just as a satirical trope…but also as a vehicle for a radical politics of liberty increasingly addressed to women.”[38] Jane Austen, however, who had grown up after the Marriage Act was passed and would have been very familiar with Gretna Green marriages, was part of a “retreat into conservative moral-literary values,” a realist who believed in making sensible marriages.[39] In several of her works, eloping couples are used as a “foil” for the novel’s main couple, who are presented as moral and pragmatic.[40]

In Pride and Prejudice (1813), Lydia Bennet and George Wickham, are “the stereotypical Gretna couple.”[41] She is underage at only fifteen or sixteen years old, while he is an officer in the army, likely with little money and no means to support a family. He had already tried to elope with Georgiana Darcy, Mr. Darcy’s younger sister, for her fortune. Elizabeth Bennet receives the news of her sister’s elopement in a letter from another sister, Jane, who writes:

“What I have to say relates to poor Lydia. An express came at twelve last night, just as we were all gone to bed, from Colonel Forster, to inform us that she was gone off to Scotland with one of his officers; to own the truth, with Wickham!—Imagine our surprise…So imprudent a match on both sides!—But I am willing to hope the best, and that his character has been misunderstood. Thoughtless and indiscreet I can easily believe him, but this step (and let us rejoice over it) marks nothing bad at heart. His choice is disinterested at least, for he must know my father can give her nothing. Our poor mother is sadly grieved. My father bears it better.”[42]

A second letter gave worse news, as the family had still not received word that a marriage had taken place at all:

“Imprudent as a marriage between Mr. Wickham and our poor Lydia would be, we are now anxious to be assured it has taken place, for there is but too much reason to fear they are not gone to Scotland…Though Lydia’s short letter to Mrs. F. gave them to understand that they were going to Gretna Green, something was dropped by Denny expressing his belief that W. never intended to go there, or to marry Lydia at all, which was repeated to Colonel F. who instantly taking the alarm, set off from B. intending to trace their route…After making every possible enquiry on that side London, Colonel F. came on into Hertfordshire, anxiously renewing them at all the turnpikes, and at the inns in Barnet and Hatfield, but without any success, no such people had been seen to pass through. With the kindest concern he came on to Longbourn, and broke his apprehensions to us in a manner most creditable to his heart. I am sincerely grieved for him and Mrs. F. but no one can throw any blame on them. Our distress, my dear Lizzy, is very great…My father is going to London with Colonel Forster instantly, to try to discover her. What he means to do, I am sure I know not…”

As O’Connell writes, the possibility that Wickham never intended to marry Lydia is far worse than their eloping – Lydia would be ruined and the family shamed. It is at this point Elizabeth realizes she would have liked to marry Darcy but believes it will now be impossible.[43] Lydia and Wickham – and Pride and Prejudice – are well-remembered today. The novel is of course still popular, but Pride and Prejudice has also been adapted for film and television many times.

In addition to adaptions of Jane Austen’s novels, Gretna Green marriages are frequently used as plot points for modern pop culture stories. Downton Abbey, created by Julian Fellowes, is one example of this. In season two episode seven, Lady Sybil Crawley, the youngest daughter of the wealthy Crawley family, attempts to elope with her family’s Irish chauffeur, Tom Branson. This plot is particularly interesting because the characters were over 21; under Great Britain’s laws at that time, she and Tom could have married in England without parental permission, making the elopement to Scotland unnecessary. Furthermore, the 1856 law that stipulated a “three-week residency requirement” for Scottish marriages to be legal had largely ended Gretna Green marriages.[44] Presumably, the creators of Downton Abbey took creative liberties to be able to include the thrill of an elopement to Scotland, demonstrating its deep-seated place in popular culture today.

“Transgender Gretna Green”

While Gretna Green has historical and pop culture significance, it is also still an important part of the United Kingdom’s current political landscape. Transgender advocates in and outside of the Scottish parliament have been attempting to pass a Gender Recognition Reform Bill since 2020, which could potentially create a “transgender Gretna Green,” allowing underage people throughout the United Kingdom to change their legal gender in Scotland.[45] The Bill, which would replace the Gender Recognition Act 2004, “aims to improve the process for people applying for legal gender recognition” in several ways, including by lowering the age eligibility for a gender recognition certificate (GRC) from 18 to 16 and removing the requirement for a “medical diagnosis of ‘gender dysphoria’ and supporting evidence.”[46]

The Bill was passed by the Scottish Parliament in December 2022 with 86 for and 39 against but was barred from becoming legislature by the United Kingdom’s Parliament in Westminster. Alister Jack – who was at that time the Secretary of State for Scotland, essentially an intermediary between the two parliaments as included in the Scotland Act 1998 – said he believed the Bill did not fit with “Great Britain-wide equalities legislation” that created women-only spaces like changing rooms.[47] He cited Section 35 of the Scotland Act 1998, which established the Scottish Parliament and gave it certain powers, “preventing the Presiding Officer from submitting the Bill for Royal Assent.”[48] Scotland’s parliament argued against this in the Court of Session in 2023 but was denied.[49]

The extent to which the idea of a “transgender Gretna Green” influenced the decision to block the Gender Recognition Reform Bill is impossible to say, but anti-trans groups recognized the potential for it and were outraged – at the same that transgender people across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland considered the possibility of living in Scotland for a few months to obtain a GRC. While the Bill was being considered in 2022, the Scottish Daily Express wrote of “transgender tourism fears as SNP urged to close ‘Gretna Green’ loophole’ in GRA reforms.”[50] The similarity this situation has to the Marriage Act of 1754 and subsequent events is striking.

The Future

While Gretna Green’s role in society has fluctuated, it has maintained a prominent position in the public consciousness since the 1770s, changing from a location of protest against the government to a plot point in our novels, movies, and television, and is now potentially moving back to its origins as a place of protest. Only time will tell how the history of Gretna Green continues to unfold.

References

[1] Bannet, Eve Tavor. “The Marriage Act of 1753: “A Most Cruel Law for the Fair Sex”.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 30, no. 3 (1997): 233-254. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30054245, 233.

[2] Bannet 234.

[3] Bannet, 234.

[4] Bannet, 233.

[5] Bannet, 234.

[6] Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. 1987. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 210.

[7] Bannet, 236.

[8] Davidoff and Hall, 221.

[9] Bannet, 240.

[10] Bannet, 241.

[11] Bannet, 235.

[12] O’Connell, Lisa. 2019. “Literary Marriage Plots: Burney, Austen and Gretna Green.” In The Origins of the English Marriage Plot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 192.

[13] Hereford Journal. 25 April 1792. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000397/17920425/001/0001?browse=False

[14] O’Connell, 190-191.

[15] O’Connell, 191.

[16] Schutte, Kimberly. 2014. “Elopement and Defiant Matches: Marrying Outside the Bounds of Propriety.” In Women, Rank, and Marriage in the British Aristocracy, 1485-200: An Open Elite? New York: Palgave Macmillan, 133.

[17] O’Connell, 192.

[18] Northampton Mercury. 27 May 1786. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000317/17860527/002/0002

[19] Hampshire Chronicle. 29 July 1797. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000230/17970729/012/0003

[20] Caledonian Mercury. 21 April 1777. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000045/17770421/005/0001

[21] Derby Mercury. 21 August 1783. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000189/17830821/005/0002?browse=False

[22] Chester Chronicle. 5 February 1802. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000341/18020205/005/0003

[23] Chester Chronicle. 19 September 1794. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000341/17940919/004/0003

[24] Leeds Intelligencer. 7 January 1777. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000236/17770107/008/0003

[25] Derby Mercury. 19 November 1779. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000189/17791119/017/0004

[26] Sun (London). 17 September 1804. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002194/18040917/010/0003

[27] Newcastle Courant. 14 September 1776. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000085/17760914/016/0004?browse=False

[28] Leeds Intelligencer. 10 September 1776. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000236/17760910/014/0003

[29] Salisbury and Winchester Journal. 30 November 1807. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000361/18071130/004/0002

[30] Norfolk Chronicle. 15 July 1780. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000246/17800715/001/0004

[31] Leeds Intelligencer. 30 July 1776. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000236/17760730/030/0005; Leeds Intelligencer. 6 May 1777. © 2024 Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited – Proudly presented by Findmypast in partnership with the British Library. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000236/17770506/007/0003

[32] “Gretna Green.” Playbill. 1783. British Library Theatrical Playbills. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal. https://blplaybills.org/.

[33] Oconnell, 201.

[34] “The Scotch Lovers; Or, The Gretna Blacksmith.” Playbill. 1803. British Library Theatrical Playbills. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal. https://blplaybills.org/.

[35] “Caledonian Lovers; Or, The Gretna Blacksmith,” Playbill. 1810-1812. British Library Theatrical Playbills. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal. https://blplaybills.org/.

[36] “The Gretna Blacksmith.” Playbill. 1813. British Library Theatrical Playbills. Public Domain Mark 1.0 Universal. https://blplaybills.org/.

[37] O’Connell, 190.

[38] O’Connell, 196.

[39] O’Connell, 203.

[40] O’Connell, 204.

[41] O’Connell, 204.

[42] Austen, Jane. 1813. Pride and Prejudice. The Project Gutenberg eBook, edited by R. W. (Robert William) Chapman. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/42671/pg42671-images.html

[43] O’Connell, 220.

[44] O’Connell, 190-191.

[45] Hallen, Nicholas. “Scottish Legal Move Could Create a ‘Transgender Gretna Green’.” The Sunday Times, February 9, 2020. https://www.thetimes.com/article/scottish-legal-move-could-create-a-transgender-gretna-green-rrsxd8sd8.

[46] “Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill.” The Scottish Parliament. https://www.parliament.scot/bills-and-laws/bills/s6/gender-recognition-reform-scotland-bill.

[47] The Associated Press. “Court upholds U.K. decision to block Scotland’s landmark gender-recognition bill.” NBC News, December 8, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/court-upholds-uk-decision-block-scotlands-landmark-gender-recognition-rcna128775

[48] “Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill.” The Scottish Parliament. https://www.parliament.scot/bills-and-laws/bills/s6/gender-recognition-reform-scotland-bill.

[49] The Associated Press. “Court upholds U.K. decision to block Scotland’s landmark gender-recognition bill.” NBC News December 8, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/court-upholds-uk-decision-block-scotlands-landmark-gender-recognition-rcna128775.

[50] Borland, Ben. “Transgender tourism fears as SNP urged to close ‘Gretna Green’ loophole’ in GRA reforms.” Scottish Daily Express, February 12, 2022. https://www.scottishdailyexpress.co.uk/news/scottish-news/transgender-tourism-fears-snp-urged-26206105