Main Body

Chapter 13: Travels of Ibn Battuta

Abu `Abdallah Muhammad ibn Battuta grew up in the city of Tangier on the northern coast of Morocco, approximately twenty miles from Tarifa on the southern coast of Spain. He belonged to a family of legal scholars and so he was educated in Islamic law as a young man, becoming a religious judge in the Maliki school (madhhab) of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence.

Ibn Battuta left Morocco in 1325, at the age of 21, to undertake his pilgrimage (hajj) to the Islamic holy lands. Not only is the hajj a religious requirement for devout Muslims, but it also was a prerequisite for aspiring scholars. Moroccans who desired to attain positions in the religious sphere would often devote a couple of years for making a trip to the Islamic east (Mashriq: Egypt, Arabia and Syria). Not only would they complete a religious obligation through such a voyage, but they would also be able to study under leading scholars from their madhhab while traveling in the east. If they made a good impression on these scholars, they would be granted a license (ijaza) to teach the work of those scholars to their own students after returning home. Scholars who accumulated numerous ijazas during their travels would improve their chances of obtaining prestigious teaching positions, or other jobs in the field of Islamic law or in religious administration, upon their return to their homelands.

However, Ibn Battuta seems to have been more interested in travel for its own sake than in forwarding his scholarly career by obtaining prominent ijazas. While in Egypt, he met a couple of holy men who prophesied that he would become a world traveler. The young man seems to have taken these words to heart, and he devoted the next 28 years of his life to traveling throughout the Islamic world. His travels took him to the central Middle East (Egypt, Arabia, Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Arab Gulf), down the eastern coast of Africa, across the Sahara desert from Morocco to West Africa, through the Anatolian peninsula (even visiting the city of Constantinople, which was still governed by the Christian Byzantine empire at that time), and throughout Islamic central Asia, India, the Maldive Islands, and East Asia. He finally returned home to Morocco in 1354, where he proceeded to dictate an account of his travels to the scribe Ibn Juzayy. This became his famous rihla, which has been translated into multiple languages (including three different English language translations) in modern times. It is estimated that Ibn Battuta traveled more than 75,000 miles during his lifetime, which is more than three times as far as the travels of his more famous near-contemporary, Marco Polo.

A mediocre scholar, who was hardly mentioned in the works of his contemporaries, Ibn Battuta nevertheless found sultans, local elites and holy men who were willing to assist, support or employ him throughout the regions he traveled in. A scholar of Muslim religious law was honored even in places as far away from home as India and southeast Asia. For example, he served as the Maliki religious judge under the sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq for eight years in Delhi and later for nine months on the Maldive Islands. Although some have questioned the historicity of his accounts, modern scholars Ross Dunn and Tim Mackintosh-Smith have argued that many of the details provided in his stories have been verified by other sources and that Ibn Battuta would not have known this information without traveling to these locations himself.

In many of the places that he visited, Ibn Battuta’s account is the only primary source we have for those locations at that time. His writings show the inter-connectedness of Islamic civilization in the post-Mongol world. Though politically divided, a larger sense of Islamic umma still remained. Ibn Battuta confirms the impact of Mongol depravations on Persia and Iraq, as well as the flourishing of Egyptian society during that time. He also provides evidence of the plague’s impact upon the Middle East, which he encountered on his trip back to Morocco in 1348. Yet, on the whole, the order and security of the pax Mongolica had proven conducive for the further expansion of Islam across Asia, and Ibn Battuta is a witness to the existence and nature of a large number of Islamic societies throughout both Africa and Asia. His account provides a snap-shot of the breadth and diversity of the dar al-Islam during the first half of the fourteenth century.

Due to copyright restrictions on the newer translations, the link below connects to the translation of Ibn Battuta’s rihla completed by the Rev. Samuel Lee in 1829. Despite the old English, this translation still brings to life for modern readers the adventures and observations of the greatest world traveler of pre-modern times.

The Travels of Ibn Battuta, trans. Rev. Samuel Lee

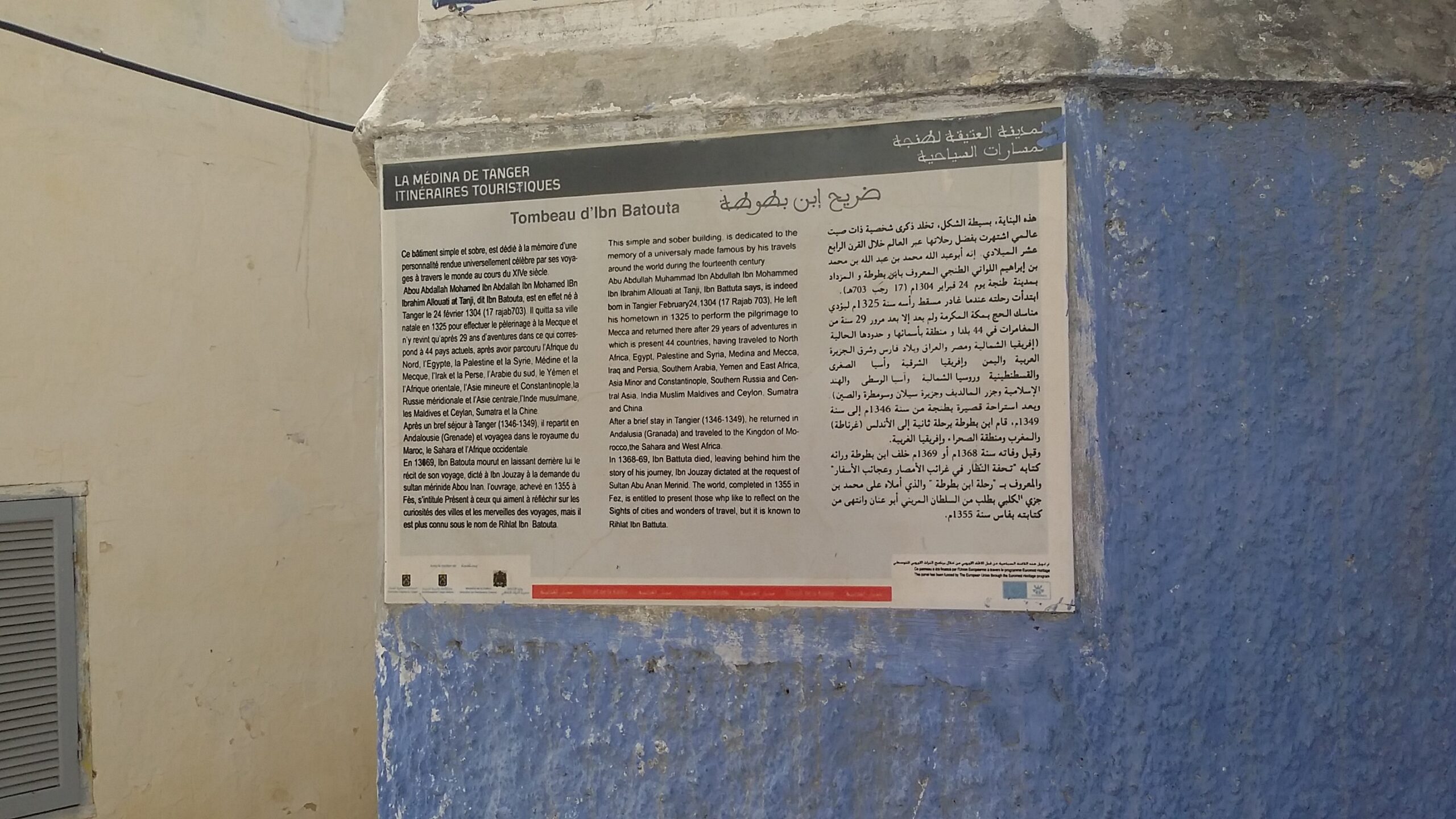

Below: plaque at the tomb of Ibn Battuta in Tangier, Morocco. Photo by author during visit to Tangier in August 2015