Main Body

Chapter 5: Islamic Society in the Iberian Peninsula

Muslims first crossed over into the Iberian Peninsula (the modern nations of Spain and Portugal) in 711 c.e. Within a couple of years, they had conquered most of the peninsula, with the except of the northwestern corner which remained under the control of Christian dynasties. From that time until the elimination of Islamic rule in Spain in 1492, Muslim civilization flourished in Iberia. At its height, Islamic Spain (known to Muslims as al-Andalus) was a prosperous, highly developed society known for its intellectual, cultural, artistic and architectural achievements.

However, beginning in the second half of the eleventh century, the Christian kingdoms of the north began to expand southward at the expense of the Muslim states. This Christian expansion, which took over four hundred years to conquer the entire peninsula, is usually referred to by its Spanish name, The Reconquista (reconquest). That term is historically contested because it implies that the Christian kingdoms were simply reconquering land that had been taken from them several centuries earlier. In reality, the Arabs and Berbers who conquered Iberia in the early eighth century took the land from the Visigoths, a Germanic group that had conquered Iberia in the early fifth century, and which practiced Arian Christianity. However, the Christian kingdoms that eliminated Muslim rule in the fifteenth century were Spanish dynasties associated with the Roman Catholic Church.

In modern times, there has been debate over how to view the Islamic societies in Iberia. The traditional view expressed in Spanish scholarship has been that these Muslim societies were made up of alien invaders who were not truly “Spanish.” However, Muslims ruled over portions of Iberia for almost eight centuries, during which time many Hispanic people converted to Islam. During these centuries there was a broad diversity of peoples living in Iberia, including Arabic speaking Muslims (Moors), Berbers, Arabized Christians who lived under Muslim rule (Mozarabs), Hispanic Christians who had converted to Islam (Muladis), Iberian Jews (Sephardis), and Muslims who lived under Christian rule (Mudejars). During the Reconquista, Jews and Muslims were sometimes forcibly converted to Christianity creating Conversos (Jews who converted to Christianity), Moriscos (Muslims who converted to Christianity) and Marranos (Jews who converted, but remained secret Jews).

Although the dominant narrative about this period is one of interfaith conflict, there is plenty of evidence of co-existence (and even sometimes friendship) between peoples of different faiths. Interfaith marriages were strictly forbidden by all three faiths, but they still sometimes took place. Over the past thirty to forty years, there has been a debate in the academic literature over whether tolerance or conflict prevailed between the different faiths in medieval Iberia. The truth is that both happened, with some regions or periods in which tolerance was more prevalent and others in which conflict predominated. What is certain is that no other part of the world saw such intensive interaction between Muslims, Christians and Jews for such a long period of time.

The most famous Muslim source on medieval al-Andalus is a long history (a recent publication of the Arabic text extends to ten volumes) produced by the seventeenth century North African historian Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Maqqarī al-Tilmisānī (d. 1632). His book, entitled Nafḥ aṭ-ṭīb min Ghusn al-Andalus ar-Raṭīb wa Dhikr Wazīriha Lisān al-Dīn Ibn al-Khaṭīb (The breath of perfumes from the branch of flourishing al-Andalus and memories of its vizier, Lisān al-Dīn ibn al-Khaṭīb) was published in Syria near the end of al-Maqqarī’s life. For more on Nafḥ aṭ-ṭīb, see the introduction to Ch 4.

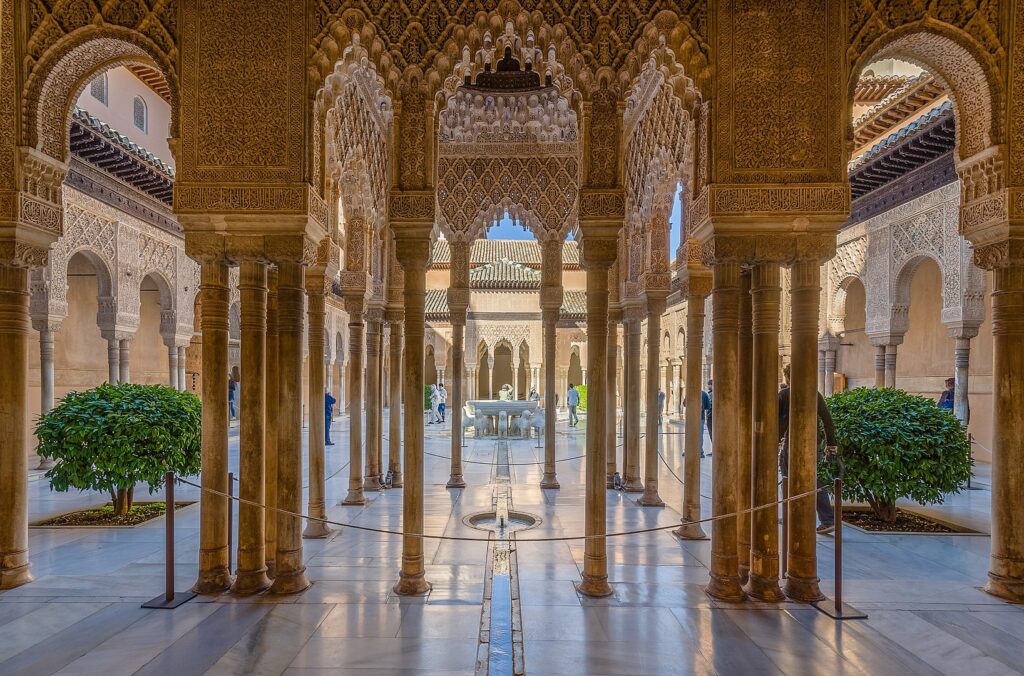

The link below takes you to Volume II of an English translation of al-Maqqarī’s text, which was completed by the Spanish scholar Pascual de Gayangos in 1843. Gayangos didn’t translate the full text of Nafḥ aṭ-ṭīb, but rather selected narrative portions to translate, for the most part passing over the extended sections of poetry that are prominent in the Arabic language original. He also did not translate the portion of the book that deals with the life of the famous Andalusian vizier, Lisān al-Dīn ibn al-Khaṭīb. Rather, Volume II traces the history of al-Andalus from the original Muslim conquest to the final conquest of Granada in 1492 by the so-called Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, which ended Muslim rule in Spain. The book also includes appendices that contain excerpts from other Muslim historical sources that discuss this period. The images below are from the courtyards of the Muslim Nasrid palace in Granada, which was the capital of the last Muslim dynasty in Spain. There is also a map of Iberia from the early ninth century at the top of this page, showing the boundaries of al-Andalus (emirate of Cordova) and the Iberian Christian kingdoms (kingdom of Asturia and empire of Charlemagne) at that time.

The History of the Mohammedan Dynasties in Spain by Ahmad al-Maqqari

By Liberaler Humanist – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=94617795