Section 3: Making It Work

Financing Structure: Piecing Together the Capital Stack

One of the most instructive aspects of the Van Aken District project is how the financing was structured. The project blended private capital with a wide range of public funding tools. The capital stack refers to all the different sources of money used to pay for a development project. It often includes a mix of private investment, bank loans, public grants, and other financial tools. Each plays a different role and carry different levels of risk and reward.

This section details the $91 million project spent as part of Phase 1 construction. RMS, the developer, provided the majority of funding, $76 million in private investment, which included both their own money (called equity) and loans from banks. However, the project would not have been feasible without substantial public participation to help close the gap. Shaker Heights and its partners assembled around $15 million in public loans, grants, and incentives to support the project. The city, school district, and RMS also agreed on a tax increment financing plan that reduced RMS’s property tax liability for a set period.

This careful layering of funding sources is what made the project financially possible.

And, of course, that’s in addition to the initial $18.5 million in federal and state money used for street reconfiguration. Though the funds didn’t go directly into buildings, they made the entire project possible by delivering a build-ready environment at no additional cost to the developer.

Private Investment

For a development like Van Aken, private investment is a major part of the funding mix. In this case, RMS, the developer, contributed about $76 million in private funding. This came from two main sources:

- Equity – This is the developer’s own money or money from their investors. For this project, RMS contributed about $24 million in equity. It showed they were serious about the project and are willing to take on some risk. Equity usually comes from the developer’s savings, business profits, or funds invested by partners. RMS brought on a partner for the project: the Cleveland International Fund, which invested $27 million. This private equity fund raises capital from qualified international investors and directs it into U.S. development projects like the Van Aken District.

- Loans – Developers often borrow money from banks or other private lenders to pay for construction. These loans must be paid back with interest, usually from rent or sales once the project is built. Before giving a loan, banks will look closely at the project’s financial plan to make sure it will generate enough income to cover the payments.

For this project, RMS took out a $25 million construction loan from a private lender.

Figure: Private Financing Sources for Phase 1

This combination of equity and bank loans formed the foundation of private financing. For these types of projects, developers build detailed financial models to show investors and lenders that the project is feasible and likely will earn enough to repay loans and provide returns.

Expected Internal Rate of Return

Developers and their investors generally expect about a 10% annual return on their equity after operating expenses are paid. Over the full term of the investment, the overall internal rate of return usually needs to average closer to 15% per year. Internal rate of return (IRR) reflects the projected annualized return on a project with multiple cash flows. IRR is a financial metric typically used in project finance that helps businesses assess the profitability of long-term investments.

If projected returns fall short of these expectations, the project is unlikely to move forward. For Cleveland-area projects, this serves as a useful rule of thumb when reviewing development proposals.

In some cases, local developers or investors may accept lower returns (perhaps 7–8%) for projects they view as passion projects or as having significant community value.

State & County Loans & Grants

The Van Aken District also benefited from state and county development programs that provided low-interest loans and direct grants. Cuyahoga County, for example, contributed a multi-million-dollar loan through its casino revenue development fund.

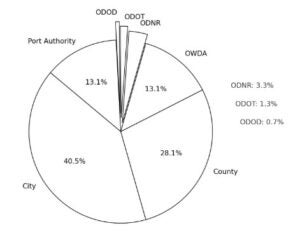

Several public sources supported different parts of the project:

- $4.3 million low-interest loan from Cuyahoga County’s casino revenue development fund.

- $2 million subordinate loan from the Ohio Water Development Authority (OWDA) for stormwater upgrades.

- $500,000 grant from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) for the park space.

- $200,000 from the Ohio Department of Transportation’s (ODOT) Jobs & Commerce program for roadwork.

- $100,000 from the Ohio Department of Development’s (ODOD) 629 Roadwork Grant.

- A sales tax exemption on construction materials arranged through the Cuyahoga County Port Authority (estimated value: $2 million).

This public investment reduced risk, closed funding gaps, and allowed the developer to proceed with construction.

City Contributions

Shaker Heights also made direct contributions to the project. The city committed a $6.2 million performance-based grant, which was financed through municipal bonds and disbursed once the developer secured other financing and tenant leases. This grant represented a direct investment in the city’s long-term vision for a downtown.

The city spent funds on land acquisition and site preparation, including the demolition of aging structures on city-owned parcels and coordination with the county to clear the site. These actions further reduced costs for the developer and helped accelerate the construction timeline.

Figure: Government Funding Sources for Phase 1

How Developers Value Government Grants vs. Loans

While government grants and loans both help close a project’s financing gap, they are not equally valuable.

A government grant is money provided by a government to support a project or activity. A grant reduces project costs dollar for dollar and never needs to be repaid, which makes it highly valuable to a developer. A government loan, by contrast, is money borrowed from a government agency that still has to be repaid, although it may offer lower interest rates than private financing. Because of this, a grant dollar is often worth five times or more as much as a loan dollar in terms of direct benefit to the project, depending on the project’s timeframe, interest rates, and risk.

So, while the pie chart above might give the impression that loans from Cuyahoga County and OWDA are as beneficial as grants from the city or ODNR, the grants provide greater financial value to the developer.

Tax Increment Financing (TIF)

One of the key tools Shaker Heights used to help pay for the Van Aken District was tax increment financing.

Tax increment financing (TIF), is a tool allowed by state law that helps pay for development projects. When a project increases the value of a property, the developer agrees to make special payments instead of paying higher property taxes on that increase.

A payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) is a payment made to a local government by a property owner or developer instead of paying traditional property taxes. These payments are usually agreed to as part of a development deal and are often used to fund public improvements or services that support the project. Such improvements or services can include things such as building or upgrading roads, sidewalks, and utilities, creating public parks or plazas, improving transit access, or maintaining public safety services such as police and fire protection. These investments are typically tied to supporting the development and its surrounding area. In this case, PILOTs funded the parking garage.

This is different from raising taxes on everyone to pay for the project. Instead, the public improvements needed for the new project pay for themselves by using the developer’s PILOT payments.

TIF agreements are limited to a specific time period (such as 25 years) after which time the PILOTS end and the developer pays regular property taxes on the increased value of the property.

In Ohio, school districts rely heavily on property taxes to fund education. In the absence of a TIF agreement, the schools would receive the benefit of the property tax increases so the school districts must be a party to the TIF agreement. The main arguments for the schools to participate are that increased development helps the community and the schools, the development may not occur without the TIF and the TIF causes no loss in revenue to the schools in that they continue to collect all property taxes on the value of the property before the development. Moreover, the schools generally receive a percentage of the increased taxes from the development since most TIF agreements do not defer all tax payments from the value of the increase but generally something like 75%.

This still allows the schools to benefit from a significant percentage of the increase (perhaps 25%) during the TIF and from all of the increase when the TIF expires. The city worked effectively with the schools and developer to achieve a satisfactory TIF agreement.

City planners and staff later said this agreement was one of the most important reasons the project could move forward. It gave the developer confidence that the city was committed to supporting the project financially without putting the city’s general fund at risk.

Bringing in Outside Expertise

Sometimes cities or developers bring in outside experts to help structure the public financing for projects like this. For the Van Aken District, the developer worked with Project Management Consultants (PMC) Financial Services to apply for and structure incentives for the redevelopment. Levin School graduate Ken Kalynchuk, who earned his MUPD in 2016, joined the effort midway through. He assisted the city and developer with applications for the OWDA loan and the ODNR grant and contributed some work on the TIF.

Assembling the Capital Stack

All told, the capital stack combined private equity, bank loans, state and local government resources to reach the total $91 million needed for Phase 1 of the project. The financing was assembled over several years.

One by one, the pieces fell into place. Grants, loans, tax tools, and city funding worked in tandem with private equity and bank financing. This layered approach made the project financially viable in a location that otherwise might have struggled to attract private development on its own. The complexity of the capital structure illustrates why the project took years to develop: no single source could fund it alone.

As city leaders later reflected, this model helped demonstrate how public-private partnerships can be used to revitalize aging inner-ring suburbs.

Discussion Questions

Why was a layered financing strategy necessary for this project?

What are the risks and rewards for public entities when they support redevelopment through grants, loans, or tax tools?

References

Menesse, Tania. 2016. “The Van Aken District.” Economic Development Journal 15 (2):43-50.

https://www.freshwatercleveland.com/features/VanAkenPlaceMaking080416.aspx

https://shaker.life/community/city-at-work/transit-oriented-development-then-and-now/