Main Body

Chapter 25

I HEAR many things said about me, or hear reports of things said, that are anything but complimentary. I am aware that in the heat of campaigns my name is kicked about on the public platform. It is to be expected. It is part of my business. It is the inevitable consequence of being connected with a fighting newspaper. People would not be human, if they did not fight back in their own way.

An example is the election of Anthony J. Celebrezze. Tony Celebrezze is the current Mayor of Cleveland. His political experience, until he first ran for office himself in 1950, was confined to working with his brother, the late Frank D. Celebrezze. Frank had been an Assistant County Prosecutor, had been briefly in the thirties a Municipal Judge, and later was Safety Director in the cabinets of Lausche and Burke.

One day I was walking on a downtown street toward my office when a small, thin, intense-eyed man stopped me. This was the older of the brothers, Frank. Many times he and I had fought over issues, but we had never fought over this man’s basic honesty or independence. He was one of the mosthonorable men in the city.

That day Frank had something on his mind. He wanted to call my attention to his young brother Tony, who was making himself a student of government and was ambitious for public office. “Tony is growing fast,” Frank said proudly. “He’s independent. One of these days I would like to see him sit in the Mayor’s chair. He would make a good Mayor.”

Tony Celebrezze is an immigrant Italian whose father, after living some years in America, had taken his family back to Italy. Later, when Tony was still a babe, they returned to Cleveland.

Tony worked at odd jobs — as newsboy, freight handler, anything he could get — to pay his way through school. He passed the bar examination in 1936, and then got his first public appointment. He was hired to do legal work for the Ohio Unemployment Commission.

Tony stepped out on his own in 1950 as a candidate for State Senator at the Democratic primaries. With little support, he was nominated and elected. In the Ohio Senate, where Democrats were few, he stood out conspicuously. He had a flair for oratory — and when he took the floor he attracted attention. He became popular with the Republican majority, and formed strong friendships there. In this session Frank J. Lausche, the independent-minded Governor of Ohio, was not always seeing eye to eye with the Democratic floor leader, and he often leaned heavily on Tony Celebrezze to help him carry out his program. Celebrezze was regarded in some quarters as the unofficial spokesman for the Governor — although, on some issues he differed vigorously with the Executive.

At the conclusion of the session, Celebrezze was rated among the four top men in the Senate, and top among the Democrats — an unusual situation for a young first-termer.

At that point Tony Celebrezze’s “troubles” began, because he insisted upon following his own conscience. This was what attracted The Cleveland Press to him.

In 1952, he sought renomination. He engaged in a running fight with Ray T. Miller, the Democratic chief, because he chose to support Michael DiSalle for U.S. Senator over James M. Carney, the choice of the Miller organization. Tony was chastised by the organization for this defection; nevertheless, he carried the election, leading the ticket in the primaries and proving an easy winner in November.

In the 1953 session, Celebrezze and the Democratic floor leader were at war frequently — and his break with the organization was wide open.

Tom Burke decided not to run for another term as Mayor of Cleveland. The Democratic organization quickly drafted County Engineer Albert S. Porter as its candidate, while the Republicans got behind William J. McDermott, Juvenile Court Judge, who had resigned to enter the race and was regarded as the favorite to win.

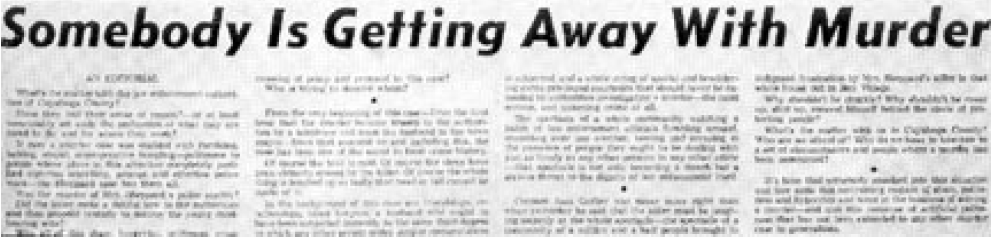

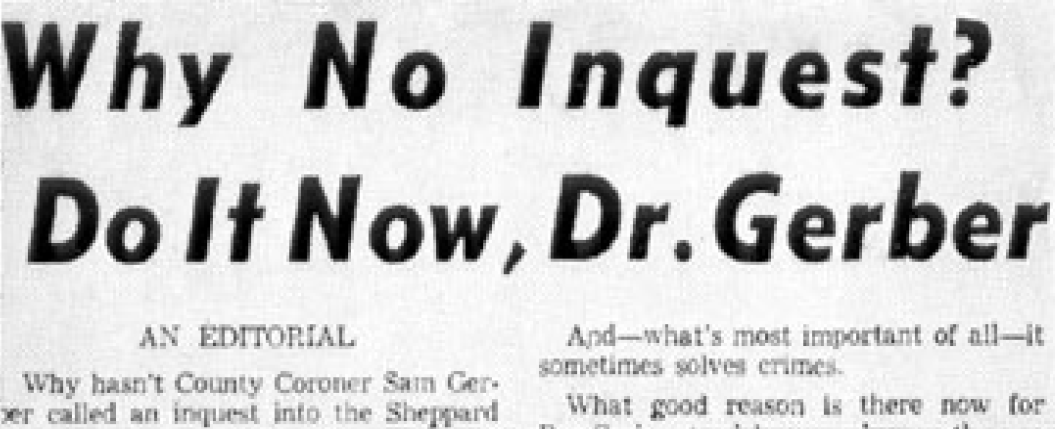

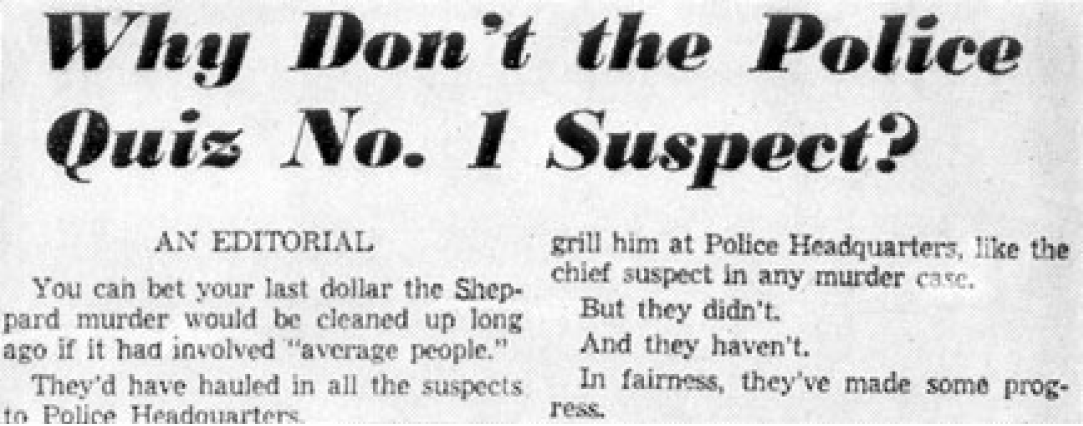

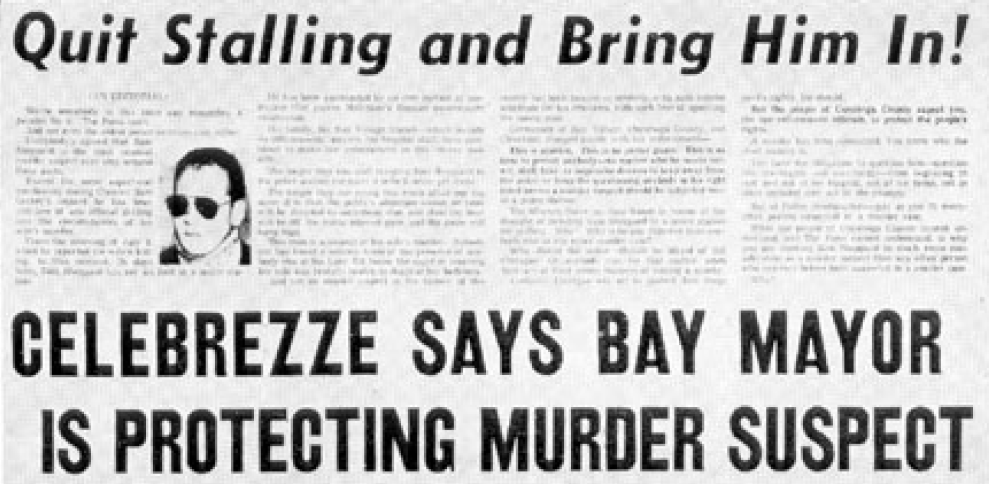

THE SHEPPARD CASE

I remembered Frank Celebrezze’s remark to me about his younger brother, Tony — and recalled, too, how courageously Tony had handled himself in the Legislature. That afternoon, after talking to him, I sat down and wrote an editorial for Page One vigorously endorsing Tony Celebrezze for Mayor as an independent — as a man completely free from boss control, controlled only by his own conscience.

Tony took the paper out to the hospital where Frank, whom he worshiped, was now gravely ill, and read the editorial aloud to him. I’ve always been glad Frank knew about that editorial. Three hours later he died.

The other two newspapers in Cleveland were divided in their endorsements — The News for McDermott, The Plain Dealer for Porter. Retiring Mayor Tom Burke, who had sat in on the meetings drafting Porter, kept neutral in the campaign. Lausche campaigned for Celebrezze, praising him for his work in the Legislature.

This was a run-off primary with the first two winners confronting each other at the regular November election. It was generally assumed that McDermott would come out first, Porter second, and Celebrezze third. Celebrezze won by a substantial margin, topping McDermott with Porter third. In theNovember election Celebrezze beat McDermott decisively.

It is true that The Press had actively supported Celebrezze, and might thus have had something to do with his decisive victory. But some people started to call Tony Celebrezze “Louie’s Mayor” — saying that he took his instructions from “Ninth and Rockwell,” where The Press building is located. They talked, knowingly, about a “private wire” between The Press and City Hall.

There was no truth in that.

Grandpa Lucien Bonaparte used to have a good many wise sayings which I have remembered all my life, and one of them came in handy now: “Don’t ever be concerned about anything people say about you, unless it’s true.”

It is now almost forty-five years that I have been in a business where there is continual controversy — where there are almost always two sides to every story — where vigorous positions on both people and questions are taken — where crusades are launched and battles fought — where it is sometimes necessary to condemn people as well as to praise them.

It is inevitable that from it all there is distilled toward an editor some ill feeling — some doubts and suspicions — some charges of arrogance and thirst for power — some notions about bossism and political maneuvering.

William Allen White warned me against this many years ago.

“There will be times, Louie,” he said, “when you wish you’d pulled up stakes and left your hometown. It’s a penalty we have to pay in our business. When we do something people like we are cheered. When we do something they don’t like, they forget what they cheered about and jeer — and sometimes, the jeers sound louder in your ears than the cheer. You have to go on doing the very best you can, and hope that in the end what you are, the motives which prompted you, the fairness by which you appraised things, will come out, and that people will get to know you so well they’ll just take you for what you are. If you can get to that place with the people in your home town, that’s about all you have a right to expect.”

The mixture of equal parts of William Allen White and Grandpa Lucien Bonaparte Seltzer — together with whatever I have learned about the people in my home city of Cleveland — has been an elixir that stimulated me sufficiently to withstand some bad moments. Fortunately, they have been relatively few.

I provided another spectacular example of how and why a newspaper editor gets the “political boss” tag fastened on him in the election of November, 1955, involving a young Cleveland lawyer named Tom Parrino. The chances are that Tom Parrino spent less to get himself elected a judge in a big city than anybody in modern political history. It cost him less than $50.

The Cleveland Press had been watching Parrino for quite a while. He was able, vigorous, courageous, and independent — qualities which we, as a newspaper, like in public officials.

Tom is a native Clevelander, although the son of Italian immigrants, like Tony Celebrezze, the Mayor. By an interesting coincidence he worked his way through the same school where Celebrezze struggled to graduation as an honor student — Ohio Northern University. Tom passed the bar examination in 1942 and promptly went into the Army, even before he had time to hang out his shingle. He came out of the service in 1946. That is only ten years ago, but in that decade Tom Parrino came up in public esteem — and in the esteem of The Press — like a self-guided projectile.

For nearly five years Parrino was at the trial table in nearly every big case tried in the criminal

courts around Cleveland. He came to be one of the best trial lawyers in the Prosecutor’s Office.

His big break came in the sensational Sheppard trial in 1954. Parrino was one of the trio of prosecutors who carried the case for the State versus Sam Sheppard. His deft handling of witnesses, the skill he displayed in the courtroom, the thoroughness with which he had prepared evidence introduced by the prosecution brought him to the attention of the whole Cleveland Bench and Bar — and to the specific attention of one of Cleveland’s largest and most successful law firms, Squires, Sanders and Dempsey. The firm was looking for a trial lawyer — and in June, 1955, offered Parrino a job. He accepted the appointment and left the Prosecutor’s Office.

He had for practical purposes put public office behind him forever. “Forever” wasn’t very long.

In the fall of 1955, David C. Meck, an incumbent judge, died suddenly. At the time of his death he was up for re-election, and had been unopposed. It was held that there was no time to replace him on the ballot. It was also ruled that his place could only be filled by a write-in vote at the November election. A great many lawyers entered the write-in campaign. Bernard Conway, the Chief City Police Prosecutor who had the support of the Bar Associations and the other two Cleveland newspapers, was the favorite in the list.

The Press heard that Parrino might be receptive to the idea of running for the write-in election. He was by far the ablest of any who had either announced, or been considered. The Press moved in quickly and persuaded Parrino to make up his mind.

By this time the election was only one week away. The other candidates had a considerable head start, and at first the experts scoffed at the idea that Parrino had a chance. Toward the end of the election it began to look as if that picture had changed.

Because of the shortness of time before the election, The Press had to hit hard and often. Even more important, we devised some exceedingly simple suggestions on how to write in the name, making use of diagrams and sample ballots to clarify the procedure.

The Bar Associations, while admiring Parrino himself, felt that his campaign broke into their own slate of candidates, as, of course, it did. Usually, all things being equal, The Press would so far as possible go along with the Bar’s recommendations, since they canvass the field thoroughly. Nevertheless, as in other instances of the past, we believed Parrino to be so exceptionally well qualified for the Bench that we were willing to risk incurring the Bar Associations’ displeasure.

Parrino won. He won big, leading by more than two to one over the nearest man on the list, the generally supported Bernard Conway.

As was true of Mayor Celebrezze, some of the town’s livelier conversationalists tagged Tom Parrino as one of “The Press Boys” — as one of “Louie’s Stable.” Most of the people of Cleveland recognized our support of Parrino for what it was — and is — a newspaper’s honest judgment about good men in public office. This is where democracy is made or broken — and this is where a newspaper’s obligation clearly rests, if it is genuinely concerned about the security, stability, and safety of the community which sustains it in business.

The Press is the first to take issue with, fight against, or otherwise disagree with any person, including those it may have sponsored or vigorously fought for in an election campaign. We assume no obligation, extend no blank check to anyone. The public acts of an official we’ve helped elect are scrutinized, by our editorial “eye,” in exactly the same way as those of an official we have opposed for office. We recognize only one obligation — our obligation to the public which reposes its confidence in our newspaper. For that confidence the least we can do in return for people is to fight eternally in their interests, with courage, vision, vigor, and forthrightness.

I have a simple philosophy by which my whole newspaper life has been guided — especially as Editor of The Cleveland Press. It is that whatever is in the ultimate best interest of the community is selfishly in the best interest of The Press. It is up to us to help the community grow and prosper, to fight those things which are harmful to it and to fight with equal vigor for those things we believe will make the community a better place in which to live.

I have one more basic principle, one that has enabled me to go through many hard-slugging political campaigns with few scars. Not by so much as lifting an eyebrow, not by telephone, by letter, or in any other way, have we ever sought to obtain any favor, any job, any privilege, from anybody in public life, no matter how trivial, or for whatever purpose. We will not confer with anyone other than in the columns of our newspaper about any matter having to do with either government or politics. We are a newspaper, wholly and exclusively — and in no way concerned with or interested in political tactics, strategies, or groups. We are either Republican or Democratic depending upon the fitness of the candidates for a given office. We are independent of any party, group, or special interest of any kind whatever. We are free to make our own choices, take own position, fight for or against whatever we think is right or wrong.

Even in local matters, there is sometimes a penalty attached to taking a stand. For example, I live in a suburban neighborhood, on the near side of a valley with a narrow bridge over it. The phenomenal growth of our metropolitan community has resulted in serious traffic congestion there. The only solution is to build a new bridge. It is proposed that the approach be routed through the neighborhood in which we live, cutting straight through some of my neighbors’ property and, in fact, right at the back line of my own.

The Press favors this proposed bridge route as being essential to the best interest of the greatest number. My neighbors are incensed, because they believe that I have betrayed them. I understand exactly how they feel. In fact, if somebody else were editing a newspaper that favored a through route on the back line of my property, I would feel the same way. But I cannot betray my own trust as a newspaper editor.

Early in our business we have to make up our minds to take the bumps and bruises that come our way. We live in a business where we give; by the same token we must learn to take.