Twenty-Five Stories

6 Shooting from the heart

William Wynne

“I saw him on an ash limb by morning’s golden yellow light

Among shimmering green leaves after winter’s flight”

~”Morning Song,” photograph and poem by William “Bill” Wynne

Once in a while, a peaceful and mundane scene springs to life. That’s the case with “Morning Song,” the picture and couplet above. Our cottage on Charles Mill Lake in Mansfield, Ohio, was the scene of peaceful messages. In the early morning, while photographing daisies from the patio deck, the air was interrupted with the melody of a Song Sparrow. He continued his song so beautifully that I called the family out to hear it. The land drops off the back sharply toward the lake, adding another 10 feet of elevation to the deck height, so I had a 20-foot high vantage point – a bird’s point of view.

The first photo I published was in YANK Magazine during World War II and was taken only two weeks after I got my destined-to-be-famous dog, Smoky, in Nadzab, New Guinea. We were just transferred into the 26th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron of the Fifth Air Force. I borrowed a Speed Graphic camera from supply and placed her in a helmet inside my tent. (It was important to have a known object in the photo to show the true size of this four-pound dog. What better scale than a GI’s helmet?)

There was no way of knowing at the time that her expression would reflect the epitome of happy anticipation involving what our lives would become during war and peace. Sixty years later, the photo became the model of three bronze memorials of Smoky, two in the United States and one in Australia, created by sculptor Susan Bahary.

Each phase of my photography is based upon what I learned while running the streets and fields in Cleveland, and from my companions before I turned 18.

What makes us who we are?

My wife Margie had two sayings: “Bill describes his photos, get out the violins” and “Bill is going to begin when he was 6 years old.” And that’s where I’ll begin because in life, and in the arts in particular, your view of the world is the summation of life’s experiences that start at a very early age. Those early experiences reflect in many ways your life as a whole. For some, early negative experiences can result in defeatism. For others, such experiences springboard into inspiration.

There are advantages and disadvantages to everything.

There can be influencing factors. For example, whether someone is part of a large or small family, or a family with no children. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. Further, the difference between growing up in a nuclear family or broken family adds to the mix that can affect one’s life. A wealthy or a deprived upbringing, and having siblings or not can make a difference. How you make life choices may be influenced by the kids you played with, which may be absorbed negatively or positively.

I was from a broken family.

Dad took off when I was 3 years old. I spent two years in the Parmadale Children’s Village of St. Vincent de Paul in Parma, from 1928 to 1930, with 400 other children. There were 40 kids to a cottage each run by one nun.

Coming home to my mother at age eight, I was a poor student who had flunked two years in grammar school as I ran the streets and fields of the West Park neighborhood of Cleveland. This is where I gained my most valuable education; I have drawn upon this my entire life. I cannot emphasize enough the value and sheer pleasure involved in the freedom of running the streets. However, this was not conducive to traditional homework and study (the disadvantage), and thus the failures. The streets were the foundation of who Billy Wynne was and is: the dog trainer, the inventor at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (later, in 1958, theNational Aeronautics and Space Administration), and the photojournalist with unusual views.

At age 20, I graduated from West Technical High School, where I specialized in horticulture, a Cornell University three-year program, along with one year in elective photography. During this period, my high school grades moved from Ds to Cs. Mr. Howard, an accountant neighbor, would say, “Bill is going to amount to something someday,” giving me an unforgettable upward lift in spirits. Meanwhile, my family would ask, “I wonder what will become of Billy?”

Following high school, I was fortunate to be associated with highly educated professionals. The Air Force in WWII required at least a 100 IQ score. My 26th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron had college professors working in photography, not to mention the bright and young “just out of high school” pilots. As top scientist and friend Irving Pinkel said, “Bill learns by osmosis.” (Pinkel worked for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration). My work at NASA Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory followed Air Force schooling in laboratory and aerial photography and having served two years overseas in the Pacific Theater with the 26th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron (New Guinea to Okinawa), to the war’s end. I also did a three-month stint in Hollywood as a motion picture dog handler, another continuing story.

I was hired for NASA’s Flight Icing Research Program as an aerial photographer. I learned so much over the seven-year period I was there. At end of the first three years, I became a “photo engineer,” and I invented a camera timer and other photo technology for the Full-Scale Aircraft Crash Fire Program. The timer illustrated the true speed of any motion picture camera within 1/10th of a second.

With my large family and low pay, and with much regret on my part (and my supervisors), I had two weeks to decide whether to take a job at the Cleveland Plain Dealer in the photo department. By switching jobs I went from working 25 years into the future to working 25 years into the past. The PD was getting racetrack results in the sports department via Morse Code, using dots and dashes – 19th century technology. I was hired to replace Ed Solotko, a fine photographer, working on The Sunday Magazine.

So what is a SPEAKING photograph that has a message?

Today, most photos are images that are captured by millions of people everyday by smartphones. They are, by and large, merely “let me show you something.” Then, there is photojournalism, a form of communication involving photography and journalism that, unfortunately, often just “shows something” as well. Few news photos really say something. Digital cameras can shoot multiple frames per second, and the photographer can select the best frames. In my early days, cameras were cumbersome, and required several steps of preparation for each shot, going through the routine again and again. Timing by the photographer in action photos was critical.

So, what can photographs SAY? Oh, so many things. A photograph can record a sacred scene that can generate tears, or deliver an instant smile.

It can be a symbol so profound it says it all.

Photography is so often like music rather than art; often an event building to a crescendo.

On a slow day for hard news, “weather art,” stand-alone photos or people or nature, would more than likely make Page 1. Photographers were asked to look out for “weather art.”

Readers are overwhelmed by gloom every day, and always hunger for some good news.

My good friend Bill McVey, a great artist, teacher and the sculptor of the Winston Churchill Statue in Washington, D.C., was a great admirer of photographers. He demonstrated for me how a photographer is similar to a javelin thrower. Leaning in a low backward stance of a javelin thrower and pointing with his arm along an imaginary javelin line up toward the sky, he proclaimed, “You point to an imaginary sky spot, get ready – and then thrust yourself with all your might.” Then he followed through by standing on his left leg with his arm and forefinger still pointing at the spot that followed the imaginary release of the javelin – frozen in midair.

“This is a photographer” exclaimed Bill. He gathers all of his worldly knowledge into a compressed self and suddenly, with his timing, presses the shutter with the forefinger and the mental power of everything he is – and it all comes out in a tiny ‘click.’ That is a photographer.”

Thank you Bill. I never thought of it that way.

As my wife Margie said, “Now you see why Bill explains his photos.”

So there you have it – shots from the heart, from a sometimes funny guy.

~

Photographer William “Bill” Wynne was interviewed by Dave Davis and Bill Barrow on Jan. 27, 2018. The following Q&A was edited for space and clarity. You can listen to the entire, unedited interview below. A transcript of the interview can be found at the end of this piece.

Davis: So, for an image, what are you looking for? What’s a Bill Wynne picture?

Editor’s note: Wynne opens a scrap book of photographs, newspaper clippings and note’s about his life and work. He points out a picture from the day President John F. Kennedy was shot.

Wynne: What had happened- Gordon Cobbledick was the sports editor. And Cobby came into the photo lab about noon and he says, “Hey Bill, any photographers here?” I said, “No, what’s up?” He said, “Well, the president’s been shot down in Texas and an AP photographer saw blood.” So, the story (was) still coming over the wire at this point. And he says to me, “Will you go out and tell the people in the city room and I’ll go to the brass’ offices and I’ll tell them.”

So, I’m looking around for a picture and there was no picture there. I went out on the street and nobody knew about it yet. I look at St. Peter’s across the street. It’s diagonal from The Plain Dealer. St. Peter’s was a high school. I’m waiting and waiting, and I thought someone’s going to have to know something about this and sure enough, all of a sudden, I hear a lot of sobbing and I look and the kids are filing out through the corridor to go to the church to pray.

There were two white girls and a black girl (who) came out and I got the pictures of the teachers sobbing and the kids sobbing. And so, these two came along and the black girl is crying so much that the white girl turns around and puts her arms around her.

Davis: Wow.

Wynne: And so I took a picture of that. So that became “Summation, Nov. 22, 1963.” It was a summation of the way the nation felt. Trying to get it published in The Plain Dealer was something else because no paper would ever publish any of these interracial photos.

Davis: Did they publish it?

Wynne: They had to, finally.

Davis: It sounds like such a powerful image.

Wynne: I had to go to Ted Vorpe and get Bill Ashbolt to put it in the paper. Ted Princiotto came to me and he had the four pictures. He wanted the sobbing kids and the teachers, and that picture and Bill says, “No we haven’t any room in the paper. There’s too much stuff coming from Texas.” So, OK, then I said to Ted Vorpe, he was the head of photography at the time, “I think this picture is an important picture. It ought to be published.” He said, “I agree with you Bill.”

So, he went over and talked to Bill Ashbolt and they put it in a first edition and killed it after that.

Davis: Really, are you kidding me?

Editor’s note: The Catholic Universe Bulletin published the picture.

Wynne: But the Catholic Universe Bulletin wire service wouldn’t pick it up.

It was only in- Well, it’s in the (Plain Dealer) first city edition. Only the city edition had it, which goes down state. We had 84,000 circulation down (state) at that time.

And so that’s the story of “Summation.” (In the print), the girls even accidentally came out where their uniforms looked like one jacket they’re both in and one dress that they’re in, (with) their four legs – black legs and white legs – sticking out the bottom.

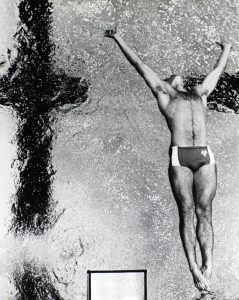

And so, I have another couple pictures that- This was an accidental picture here. I got up on a diving board at CSU. The NCAA diving championships were played that year, 1975 or ’76, I can’t remember. But anyhow after they had their competition they start practicing. So, I got up on the highest diving board. And I take the picture of this guy doing a swan dive. See it? But it was taken on Holy Thursday and here look at the cross in the water.

So (sports editor) Hal Lebovitz, being an Orthodox Jew, ran this on Good Friday in the sports page. Honest to gosh.

Davis: Did he get any-

Wynne: I don’t think so. He didn’t have any flack at all.

Davis: Did anybody ever complain about the picture of the school girls hugging after the assassination? Did any readers ever call anybody?

Wynne: No, nobody ever did. If they did, I didn’t hear about it.

Davis: So, it was just journalists being anxious about what their audiences might think.

Wynne: That’s right. So, this is the Lima State Hospital story.

There was abuse at the Lima State Hospital, which was (for) the people who didn’t get the death sentence because they were mentally ill. So, they threw them in the Lima State Hospital. And they had these guards there, they used to beat the people up every day. They killed some. There’s unmarked graves there. So, we found out about it through the governor’s office.

Editor’s note: After receiving a complaint, Ohio Gov. John Gilligan asked a lawyer to investigate the claims.

Wynne: So, he calls us. And Ned Whelan, Dick Widman and I go out. Ned and Widman were changing motel rooms every day because these guards will kill you.

Barrow: Really?

Davis: This looks like it was in May of 1971, Bill.

Wynne: Does it? OK.

So anyhow. We ran a series. We ran a Page 1 story on this for 30 days straight and this was a big exposé. And one day one of these guys (at the Lima State Hospital) comes up to me, and I got the camera dangling around my neck and I’ve been taking pictures. And he said, “Who are you with?” And I pointed to (the lawyer) and I says, “I’m with him.” I didn’t tell him I was with The Plain Dealer.

I was a state roving photographer/reporter for four years.

Davis: You did some reporting too?

Wynne: Oh, yeah.

Anyhow, this woman here was kept like this in a stupor, under a shower. When she’d go to the bathroom, they’d just flush the shower down on top of her.

Editor’s note: News that the governor was sending people to Lima reached the hospital, which cleaned up its act when The PD team first got there.

Wynne: They got word up there, so they let her get up. You see she’s sober (alert) here. So, they (the governor’s representatives) look, and they couldn’t see anything wrong.

Editor’s note: But Wynne returned the next day, when he wasn’t expected.

Wynne: Here she is in a stupor.

Editor’s note: Wynne flips through his scrapbook.

Wynne: These are Newspaper Guild (awards) – best picture, best photo of the year.

And this is called, “Three Touches of Freedom.” Freedom of Expression. Freedom of Enterprise. Freedom of Religion. I just happened to get it all into one picture. And so, I was taking (pictures of) the kids… I was waiting outside. I saw the flag on the ground and I was going to see what they did with the flag. All of a sudden there’s four of them together and this little boy jumps up and touches the flag and I snapped the picture.

When I develop it, I find I got the truck in there and I got the church. It was a natural.

This picture here- I saw this bird.

Editor’s note: See picture “Morning Song” at the top of this page.

Wynne: What happened was. We’re at my cottage and I’m shooting the daisies. And all of a sudden, I hear this songbird. It’s May and (it’s a) beautiful song because this is a song sparrow. So, I go over to see him, and I got a 500 mm lens on there and I thought I’d never get the picture because it’s not particularly the sharpest lens. It’s a mirror lens.

Anyhow, I hear the bird and I go out over there with this long lens and I take one shot. I don’t think I’m going to get it. Two hundred fiftieth of a second because it’s a 500 mm lens, you got to hold that really steady. So, I shot it and I forgot about it and it was in my camera for about three or four more days because I was shooting assignments. Later, and I came back I developed them. I said, “Gee, I’ll try to print that.”

I decided I’d give it to the picture desk. They’re always looking for what they call weather art. They’re gonna run it on Page 1. Something happened with the Pope. So, they bumped it inside to Page 6. And so, all of us got in that morning and the phones were jumping off the hook. Calls from all over the country. They were coming from everywhere.

(Publisher) Tom Vail’s office was getting them. Everybody was getting them. We ended up getting over a thousand. Here are the letters to the editor that were written about it and they published it again. And one woman, a nurse, wrote that this older woman she was taking care of had this beat up clipping in her wallet and she was looking at it all the time. Could she get actually a print? So, we gave her a print.

And somebody else wrote and said, “Thank God that somebody sees some beauty in this world.” It was a shocker. So, then I wrote a couplet for it. It didn’t have the couplet when it went out.

Davis: They should have moved the Pope inside.

Wynne: The day when it was going out on the wire. I wrote a couplet and it was something like: “I saw him on an ash limb by morning’s golden yellow light. Among shimmering green leaves after winter’s flight.” AP ran it under this picture. So, the couplet is in there under the picture.

Editor’s note: The Plain Dealer hired Wynne because of his experience in color photography, which was new at the time.

Davis: And what year was this?

Wynne: 1953.

Davis: OK, so color was-

Wynne: Sunday Magazine was using color.

Davis: So, it was beginning to happen, but it was new.

Wynne: They were already- Vern Cady was working in it. But they needed a helper and they also needed a photographer.

Davis: Now how long were you at The Plain Dealer?

Wynne: Thirty-one years.

My comment is overall photography (is) not very well understood by journalism, journalists. And it became an arm of support (for) an article. They didn’t really know how to hire people (and) so some of the heads of photographers are questionable. I don’t want to name names.

The way you pick photographers- They were (the most) miscast bunch of guys I’d ever seen. Ray Matjasic was really good. He was a combat photographer in the Marines. He was a truck driver for The Plain Dealer and he fought his way into photography. He became chief photographer.

The brass on the upper level doesn’t understand the photography at all. They leave that go the way it’s been going for years and years. And what you end up with is a bunch of photographers that show something. They don’t say something.

The mayor of Parma Heights said, “Bill makes his camera talk.” And that was a good definition. I didn’t realize it at the time. But the camera- it might have a purpose for having a picture. And we have so many pictures that don’t really have a purpose.

You don’t see pictures that say something, like the girls with their arms around each other.

The way they worked photography and photographers in most newspapers. (If) you happen to get somebody who’s really interested in it at the higher level-

They had times where you had good people at the top and then you had better photography because they were more careful how they hired and more discriminating about what they ran in the paper. Most of it was to fill holes. It’s a place to fill a hole so you don’t have to have so much copy.

Davis: Do you remember what the circulation was at the high point?

Wynne: It was about 520,000 on Sundays.

Davis: OK, lots of readers. So, did it serve Cleveland well or not so well?

Wynne: Yeah, when I came to The Plain Dealer they used to say it was the “Grand Old Lady of the West.” But it was very conservative. The Press did have some good reporters over there too. They were highly competitive and then the News had good people.

Davis: Well, it sounds like kind of a heyday in journalism in Cleveland because you had three dailies plus the Catholic Universe Bulletin.

Wynne: Really competitive. Even the Heights paper was pretty good, The Sun.

Davis: So, when all these people were going after things and you’re competing-

Wynne: Oh, yeah, you’re competing. You had competition.

Davis: And what did that fella say, the mayor- “Your camera tells a story.”

Wynne: My camera talks. Yeah, but that’s what it should be.

It’s so easy now. Brrrrrrr and they can do it. We had to be very selective. When we took the picture, it was very selective, and you missed a lot of pictures. There was 17 ways to miss a picture. You gotta have film exposed, and the shutter has to work, and you have to have the right exposure.

Other than that, the curtain can be down in the back and blind out your picture. You could have no film in the camera, the film could fall out of the whole thing. There’s so many ways to miss the picture, that there’s hardly any ways to get it. And so, we were working with really clumsy equipment, but we made it work. And once in a while you come back to the office saying, “I missed it.”

Barrow: And then you look at the paper, the rival paper and that guy caught it.

Wynne: That could happen to you. Now, they can send it back on telephone. They don’t even come in the office.

I was not objective. I was subjective. And I’m editorializing because we’re making a statement.

Transcript

Davis: This is Dave Davis for the Cleveland Memory Project. It’s Jan. 27, 2018, lunchtime at the 100th Bomb Group Restaurant. I’m here with Barrow and legendary Plain Dealer photographer, Bill Wynne. Pull up a chair and join our conversation.

Barrow: I got a question, how did you get to be a photographer and not a PR guy?

Wynne: I was just a peon when I came into photographer. I took horticulture at West Tech [High School] and I was specialized in it. It’s a three-year course and we didn’t know it at the time, but it turned out to be the Cornell Course, three years in high school we get this. So, I take an elective course in photography, one year. I needed 10 points, so I could have taken anything, so I took photography. When I saw that I was drafted, they said, “Would you like to go to photo school.” And I said, “Yeah!”

Davis: The government sent you.

Barrow: You got to sit in a fox hole somewhere.

Wynne: Well, we still had foxholes even in the Air Corps because we were always at the front in the Pacific.

Davis: What year was that Bill?

Wynne: This would be in 1943, January. At first, they said, “Would you like to be in the ground crew of the Air Force.” I says, “Yeah!” Like being drafted I could be thrown into anything. OK, and then he started looking through there he said, “Would you like to go to photo school?” Yeah, so I went to Lowry Field for three months and we became a lab technician. And then I went to Lowry Field, not Lowry Field but Colorado Springs, Peterson Field. And then I went to aerial photo school for a month and there were 27 of us started out and only three passed the physical. It was a really a tough physical. And so, three of us passed that.

Barrow: Wait a minute, a physical for aerial photography?

Wynne: Oh yes, because you’re gonna be flying. Fliers had to have the perfect physical.

Barrow: Oh, all right. I didn’t realize it was that demanding.

Wynne: Well, you had to be able to withstand everything. You’re gonna have to take 27,000 feet of altitude on oxygen and they power dive us. There 7,500 feet a minute and we’re going … Trying to adjust our ears.

Barrow: Oh, yeah.

Wynne: I was moving the jaw and everything else.

Barrow: Excuse me, can I get the facial expression on the video.

Wynne: But anyhow. I went into photo school and got kicked around a bit. I was supposed to go to Europe with four other photographers. I don’t know what happened to three of them. I knew Bill Smythe went into pilot training, and he never finish because the war ended before he got done. But the other three guys were sent to Europe and they were having their biggest loses at that point. My buddies, I don’t know, they probably ended up dead or prisoners of war because they just knocked all the planes out of the sky at that point.

Wynne: And so anyhow, as fate would have it, I got the far Pacific and causal there were 400 of us. Ed Downy and me. Ed Downy was a private. I don’t know where he got his so-called aerial photography experience because he didn’t go to school. And he’s quite a swashbuckler. Sort of like an Errol Flynn-type. And so, I had to contend with that all the time. He’s the one who found Smoky the foxhole and didn’t like that and brought her back and gave it to another guy and so I buy the dog from the other guy.

Wynne: And I go, “Why didn’t you bring the dog back to me?” He said, “I don’t want a dog in my tent.” And so, I bought her back two days later. When I bought her I said to … He looks up he says, “I don’t want a dog in my tent.” I says, “She’s staying.” [inaudible 00:04:16] went quiet. He says, “All right. Keep her away from me. If she wins the champion mascot of the South Pacific by Yank Magazine.” This guy’s already transferred to another outfit [inaudible 00:04:27] and he came over to see the dog.

Wynne: So, I called him years later because I want to tell this story for the book and Ed had two dogs later in life, and he had kids, and he went to accounting school at Villanova [University]. And that was his story. And so, you know how lives go different. But anyhow-

Barrow: But you were aerial photography.

Wynne: I was in aerial photography and I was doing photo lab work and then because of my aerial photography, it was as good a story, Bill. But it’s in the book and what happened is they grounded us all in our squadron and put us under the infantry.

Barrow: It’s in this book?

Wynne: Yeah, they put us directly under General [Walter] Krueger, who was head of 6th Army – 100,000 men. And we were going to work with him specifically. And so, they grounded us from the Air Corps and put us temporarily into the infantry and so we made the landing at Luzon [Philippines] [00:05:27] with everybody else.

Wynne: And so anyhow, I’m losing my train of thought because there’s a million stories that deviate.

Barrow: We’ll try to get to The Plain Dealer eventually.

Wynne: Yeah gotta get back to the [crosstalk 00:05:42]

Davis: This is a lunchtime conversation with legendary Plain Dealer photographer, Bill Wynne.

Wynne: Because the government had-

Barrow: You know what four, five years ago?

Wynne: Why we did this.

Barrow: Oh.

Wynne: Well, we know we did it for the date that time three men, but it turned out there was an invasion and they [the Japanese] dropped 305 paratroops on our sister squadrons, photo recon squadrons – 25th, [inaudible 00:06:07] photo and combat mapping. And then they had a simultaneous 1,000 man landing. They wanted those airstrips back that we took four months before. So here they’re coming down and guys are running around trying to find their guns and their bullets and Air Corps guys don’t have that kind of experience and they’re all running around trying find this …

Wynne: This is something I find out four years ago. The government took all these years because there was 16 million in the service and everybody’s writing memos day to day filing them, one goes to Washington and it’s taken 70 years before they get this damn thing online. And now you can find information that didn’t exist before and that’s when I found out a lot of things.

Wynne: I asked, “What was the typhoon mean?” Pops up typhoon [inaudible 00:06:53] I just got caught in a typhoon for three days and here it turned out 292 ships in the U.S. Navy. The biggest loss in the history of the Navy happened there in that typhoon. And so, the information is there now that I didn’t know when I wrote the book 20 years ago. So, I know specifically what happened.

Barrow: Yeah, well this whole internet thing-

Davis: This is a lunchtime conversation with legendary Plain Dealer photographer Bill Wynne.

Davis: So now Bill for an image what are you looking for? What were you looking for? What was a great image to you? A great picture? What’s a Bill Wynne picture?

Wynne: Well, the girls in the school at the Kennedy assassination. What had happened [inaudible 00:07:48] Gordon Cobbledick was the sports editor. And Cobby came into the photo lab about noon … about 1 o’clock and he says, “Hey Bill,” he says, “Any photographers here?” I said, “No, what’s up?” He said, “Well, the president’s been shot down in Texas and an AP photographer saw blood.” So, it was the story still coming over the wire at this point. And he says to me, “Will you go out and tell the people in the sitting room and I’ll go to the brass offices and I’ll tell them.”

Wynne: So, they went there and I’m looking around for a picture and everybody going like this and there was no picture there. So, I went out on the street and nobody knew about it yet. I look at St. Peter’s across the street. It’s diagonal from the Plain Dealer. St. Peter’s was a high school. All of a sudden, I’m waiting and waiting, and I thought someone’s going to have to know something about this and sure enough, all of a sudden, I hear a lot of sobbing and I look and the kids are filing out through the corridor to go to the church to pray.

Wynne: There was two white girls and black girl came out and I got the pictures of the teachers sobbing and the kids sobbing. And so, these two came along and the one white girl backs off and the other two girls, the black girl is crying so much that the white girl turns around and puts her arms around her.

Davis: Wow.

Wynne: This was before integration. [crosstalk 00:09:17] And so I took a picture of that. So that became Summation Nov. 22, 1963. It was a summation the way the nation felt. Trying to get it published in the Plain Dealer was something else because no paper would ever publish any of these interracial photos because, up until ’66 when the riots happened, I was the only one doing it. So, I was taking the pictures.

Davis: Did they publish it?

Wynne: They had to finally three times. Well, they published-

Davis: But it was so important. It sounds like such a powerful image.

Wynne: I had to go to Ted [Worp 00:09:57] and get Bill Asheville to put it in the paper. Ted [Priciado 00:10:01] came to me and he had the four pictures. He wanted the sobbing kids and the teachers, and that picture and Bill says, “No we haven’t any room in the paper. There’s too much stuff coming from Texas.” So, OK, then I said to Ted [Worp 00:10:15], he was the head of photography at the time, “I think this picture is an important picture it ought to be published.” He said, “I agree with you Bill.”

Wynne: So, he went over and talked to Bill they put it in a first edition and killed it after that.

Davis: Really, are you kidding me?

Wynne: I couldn’t get anybody. I went to New York to get an award for it and I stopped at This Week Magazine and the guy said, “Bill that’s a wonderful picture but we’d lose all our circulation in the South because if we ever ran that.” He said, “We’d lose all our circulation in the South.” So that was what I was running into. So, the Catholic Universe Bulletin said [inaudible 00:10:53] Cleveland News.

Davis: Right, right, right.

Wynne: And he went over with City Editor of the Catholic Universe and then he ran it.

Davis: Ah, really.

Wynne: He ran it in the Universe Bulletin. But the Catholic Universe Bulletin wire service wouldn’t pick it.

Davis: Wow, what a story.

Barrow: I was just looking to see- What comes up under your name on the web. A lot of pictures of you and Smoky.

Davis: Well, I almost wondered about checking the digital archive, but it sounds like you’re saying it was only in a limited … that first run.

Wynne: It was only in-

Davis: I wonder if it would show up in the PD’s digital archive.

Wynne: Well it’s the first city edition. Only the city edition had it, which goes down state.

Davis: Probably not-

Wynne: We had 84,000 circulation down state at that time. Around the country, by trains, you know how we used to deliver the paper. And so that’s the story of Summation. Sometimes, you ask me about … that picture gotta be very important because it’s … the girls even accidentally came out where their uniforms looked like one jacket they’re both in and one dress that they’re in. Because their four lets, black legs and white legs sticking out the bottom.

Wynne: And so, I have another couple pictures that.

Davis: Wow, Bill, that’s [inaudible 00:12:21].

Wynne: This was an accidental picture here. I got up on a diving board at CSU. The NCAA diving championships were played that year. 1975 or ’76, I can’t remember. But anyhow after they had their competition they start practicing. So, I got up on the diving board highest. And I take the picture of this guy doing this swan dive. See it? But it was taken on Holy Thursday and here look at the cross in the water. It’s look like a galley. I won a big award with that-

Davis: Was that pure luck or coincidence?

Wynne: There were only nine awards in 50 years where I got this one in New York with the communications thing. They had about 1,000-1,200 – all religious writers from every medium. So, I got that top award, which they only give very rarely. But that was it and so that’s an important picture. So [sports editor] Hal Lebovitz [00:13:28] being an Orthodox Jew, ran this on Good Friday in the sports page. Honest to gosh.

Davis: Did he get any-

Wynne: I don’t think so. He didn’t have any flack at all. This is the Lima [00:13:42] story.

Davis: Did anybody ever complain that Tom said the picture was published of the school girls hugging after the assassination? Did any readers ever call anybody?

Wynne: No, nobody ever did- If they did, I didn’t hear about it.

Davis: So, it was just journalist being anxious about what their audiences might think.

Wynne: That’s right. So, this is the Lima State Hospital story. We had the Pulitzer taken away from us.

Barrow: I remember that. I was wondering if I could find that picture online. OK.

Wynne: But anyhow-

Davis: Wow, Bill.

Wynne: There was abuse of the Lima State Hospital, which was the people who didn’t get the death sentence because they were mentally ill. So, they threw them in the Lima State Hospital. And they had these guards there, they used to beat the people up every day. They killed some. There’s unmarked graves there. So, we found out about it through the governor’s office. We called [inaudible 00:14:46] because the air force guide was 300 pounds and he had a nervous breakdown and they put him in Chillothe [00:14:56] and the government was paying for it.

Wynne: Well, he started to beat up the guards. So, they moved him up to Lima. When he got to Lima the first thing they did was punch him around and knock all his teeth out, so he couldn’t eat, so they could drop his weight. Can you believe this? Drop his weight. So, he couldn’t eat see? His parents come to visit him and don’t know what happened to him, so they go to the governor, [John] Gilligan. And Gilligan calls [Mealbeau 00:15:24] to come in as a lawyer from Toledo to come down and investigate.

Wynne: So, he calls us. And Ned Waylon, Dick Whitman and I go out-

Barrow: Ned Waylon?

Wynne: Ned Waylon, yeah. He was a reporter for the Plain Dealer.

Barrow: I only knew him as a PR guy in the Hanna Building.

Wynne: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I knew Ned when- [crosstalk 00:15:50]

Davis: What year was this Bill?

Barrow: You knew what happened to him didn’t you?

Wynne: Yeah, he fell down the stairs.

Barrow: He went to visit his daughter in Phoenix and in the night fell down the stairs.

Wynne: Bout two weeks he died. I just had-

Barrow: Really?

Wynne: Met him about a year before. He was helping me with PR and wouldn’t charge me anything.

Barrow: Yeah, I knew him. I met him back in the 90s. And I just seen him a week before he left to Phoenix. He wanted some research on something and I dropped something off at his office. And the next thing I know he’s … Anyway, I’m sorry go ahead.

Wynne: That’s OK. So anyhow. Ned and Whitman were changing motel rooms every day because these guards will kill you.

Barrow: Really?

Davis: So, this looks like it was in May of 1971, Bill.

Wynne: Does it? OK.

Davis: I mean I just wanted to give it some- For the tape.

Wynne: So that’s good, OK. So anyhow. We ran a series. We ran a Page 1 story on this for 30 days straight and this was a big expose. And one day one of these guys comes up to me and I got the camera dangling around my neck and I’ve been taking pictures. And he said, “Who are you with?” And I pointed to [Mearbaux 00:16:57] and I says, “I’m with him.” He was the lawyer. So, I didn’t tell him I was with the Plain Dealer.

Davis: Now, who was the reporter?

Wynne: Dick Whitman.

Davis: Oh, sure.

Wynne: And Ned Waylon.

Davis: OK, right. You said that. You told me that.

Wynne: You see I was a state roving photographer/reporter for four years.

Davis: So, you did some reporting too?

Wynne: Oh yeah, I did. You’ll find I got three, four more booklets from the library they gave me with all my pages. I was doing full pages in photo essays [00:17:34]. So anyhow, this woman here was kept like this in a stupor, under a shower … She’s under a shower and when they wanted to … When she’d go to the bathroom, they’d just flush the shower down on top of her. [inaudible 00:17:50] And then there she is again. But then the news of the picture the two guys the state was gonna send back up with the representatives up there to check this out. Well they got word up there, so they let her go up. You see she’s sober here. See she’s just holding her head. So, they look, and they couldn’t see anything wrong. I took a picture of that and then I showed the next day.

Wynne: And I’m back again. Here she is in a stupor. And we … So, they did a story on me because I reported these. Well anyhow-

Barrow: Who did a story on you?

Wynne: Wilson [Hershfelder 00:18:25], I don’t know if I got about … there’s no byline here. “Lens Captures Tragedy: The Photographer”

Barrow: PD story?

Wynne: Yeah.

Barrow: OK.

Wynne: And this is a story about how I did it. So anyway, we come up for the Pulitzer [Prize] and all the editors picked us as the top prize before the expose of these … We sent 28 people of felony charges to prison and three former employees to prison. They closed Lima down two years later. But anyhow, so we put it in and the editors picked us out and we waited and waited all day and finally about 9 o’clock at night it come out and we didn’t get the Pulitzer. It had been taken away from us by the committee.

Davis: The board.

Wynne: The board. And they did that all time and tease the editors. So, Newsweek, Newsday Magazine, Paper.

Barrow: Right, Long Island.

Wynne: In New York. They had a four-day running expose of the Pulitzer Prizes. Oh, yeah 1976 or so they did that. And they mentioned us.

Davis: So, they wrote about it.

Wynne: Oh, yeah. They mentioned that the editors were furious that they had taken away our prize.

Davis: Well, you gotta question. I mean if everyone’s saying on thing and then they come in and go, “Oh no, we’re not- ”

Wynne: Well, here’s the thing.

Davis: I mean it does raise questions.

Wynne: They’re so crooked that the L.A. Times, The New York Times and Washington Post wins 10 out of every 20, every year. They just shift around and do that. They get those wins if they want any. I don’t feel too bad about knowing that because these are the Heywoods [Heywood Broun awards] that I got from the [Newspaper] Guild. I got some of them.

Barrow: What are these?

Wynne: These are Newspaper Guild best picture, best photo of the year.

Davis: Sure, sure, sure.

Wynne: Best photo of the year. This is the boy’s fishing a ball out of the sewer this one. These are all different ones. And this is three touches of freedom and I was with [General Douglas] MacArthur and [W.M] Keplinger of the changing times [Changing Times – The Kiplinger Magazine]. Well MacArthur wasn’t there but he got it from his “Farewell to New West Point” public address. Duty, honor, country. Remember that was spectacular public address that he gave. So he would have been with me and Kiplinger of the Changing Times was next to me. He was really a nice man.

Wynne: And so, this is my photo, and this is called, “Three Touches of Freedom. Freedom of Expression. Freedom of Enterprise. Freedom of Religion.” I just happened to get it all into one picture. And so, I was taking the kids … I was waiting outside. I saw the flag on the ground and I won awards from this before and I was going to see what they did with the flag. So, all of a sudden there’s four of them together and this little boy jumps up and touches the flag and I snapped the picture.

Wynne: When I get the picture and I develop it. I find I got the truck in there and I got the church. It was a natural.

Davis: Wow, wow, wow.

Wynne: And so that’s how I got $500 and the top award.

Davis: Wow, that’s a beautiful picture.

Wynne: I got to show you the award. Because JFK had this on his desk from the year before for duty, honor, country [inaudible 00:21:56].

Barrow: Say that again, he had what?

Wynne: He had this award on his desk when he was assassinated. [The award was] in the Oval Office.

Barrow: Oh, really?

Wynne: This one here for duty, honor … No, when did he write.

Barrow: What?

Wynne: He wrote that big famous book, Profiles In Courage [crosstalk 00:22:13] So he got this award the year before and I got it the next year. And we got $500 with it and we had to go to Valley Forge and try to [crosstalk 00:22:25]

Barrow: Well, you probably earned yours. I think Ted Sorenson wrote his book for him.

Wynne: Oh, did he. Well, I didn’t have that kind of luck. This book here … This picture here. I said when I brought it, took it. I saw this bird.

Davis: Are these original prints, or are they? This looks like a copy, a photocopy. It looks nice though.

Wynne: Well, I copied it.

Barrow: Laser printers.

Wynne: What happened was. We’re at my cottage and I’m shooting the daisies. And all of a sudden, I hear this songbird. It’s May and beautiful song because this is a song sparrow. So, I go over to see him, and I got a 500 mm lens on there and I thought I’d never get the picture because it’s not particularly the sharpest lens. It’s a mirror lens.

Davis: This is a lunch time conversation with legendary Plain Dealer/photographer, Wynne.

Wynne: So anyhow, I hear the bird and I go out over there with this long lens and I take one shot. I don’t think I’m going to get it. 250th of a second because it’s a 500 mm lens, you got to hold that really steady. So, I shot it and I forgot about it and it was in my camera for about three or four more days because I was shooting assignments later and when I came back I developed them. I saw, “Gee, I’ll try to print that.” And I printed it and I showed it to Helen Cullinan [00:23:50], who was the art critic at the time a very good friend of mine. And I said, “Well, Helen, what do you think? What do you do with a bird picture?”

Wynne: She said, “Well, gee Bill that’s yours. What are you gonna do with it.” I says, “I don’t know.” So finally, I decided I’d give it to the picture desk. There always looking for what they call, weather art. So, OK, I give it to the picture desk. They’re gonna run it on Page 1. Something happened with the Pope. So, they bumped inside Page 6. And so, it veered and all of us we got in the morning and the phones were jumping off the hook. Calls from all over the country. They were coming from everywhere.

Wynne: Tom Vail’s office was getting them, everybody was getting them. We ended up making over a thousand [crosstalk 00:24:36] and I got this story here. Here are the letters to the editor that were written about it and they published it again. And one woman, a nurse wrote that this older woman she was taking care of had this beat up clipping in her wallet and she was looking at it all the time. Could she get actually a print? So, she gave her a print.

Wynne: And somebody else wrote and said, “Thank God that somebody sees some beauty in this world.” So, it was a shocker. So, then I wrote a couplet for it. It didn’t have the couplet when it went out-

Davis: They should have moved the Pope inside.

Wynne: Well anyhow, that day when it was going to out in the wire. I wrote a couplet and it was something like. I saw it one an Ash lane in yellow, gold and white. Among the shivering green leaves, after winter’s flight.” So, AP ran it under this picture. So, the couplet is in there under the picture.

Wynne: Well anyhow, even now. They’ve just finished my bio for Ohio University Press.

Davis: Oh, OK, OK. Is that where you went to school?

Wynne: No, I have no college at all. I was the dumbest kid in school

Davis: I was too.

Wynne: And I was 20 years old by the time I got out of high school, but I never told anybody until I was 90 years old.

Davis: In high school, I was the perfect “C” student.

Wynne: Yeah, yeah.

Barrow: Gentleman’s “C.” Gentleman’s “C.”

Davis: Right, yeah, fair. No kidding.

Wynne: So, this is a story about-

Davis: Were you really … You weren’t really 20.

Wynne: I was 20 years-old when I got out of high school. I got held back twice in new grammar school. Well, there’s a good line if you want to look it up the 16 successful failures. And one of them is [Steven] Spielberg. He couldn’t get into a film school in any of the California colleges.

Barrow: What I liked about that story about Spielberg was that he eventually went back to finish, and he submitted as a senior project Schindler’s List. How do you turn him down? You’ve been using that List to teach for years. What are you gonna say?

Davis: It’s like having Shakespeare for high school English. Somebody had him.

Wynne: There’s a hundred of them. But I’m one of the successful failures that’s why they did my story.

Davis: Oh, is that what the story’s about?

Wynne: No, actually. They just taken me as being one of the Ohioans, who are well-known but not among Ohioans. So, these books are kind of a revelation but the done to the grammar school level. So, my book is written at seventh and eighth grade level. The problem is they took my story, which would take about 500 pages, because they got six different phases to my life. The NASA phase, I invented for them. You’ll see picture of some of the images I got in here.

Wynne: I got the Army, then there’s Smoky and they wanted to lock on the dog because they thought the kids would hold an interest in reading the book because of the dog story. And then the postwar and all of those things. And they’re condense it into 20,000 words. Well, holy smokes. My book is only that thick and it’s got 150 pages, there’s 78,000 words in that book and you can see how small it’s gonna be and you’re gonna have photos in it too.

Wynne: This almost killed the biographer because they trying to cut this story down into some sort of working thing. It took her over a year. We worked a year. I’m from Columbus and we’d go up and we’d work on it. So that’ll be coming out in August. But anyhow, this story should really be told in a full-size book because it’s got great photos along the away. Here look at the … Here’s the NASA pictures. This is Erma the Body.

Wynne: That was in the May show. There were only 11 pictures picked that year. I made a 30 x 40 print. And they put it with … It was one of the first poster pictures … that became a fad after that. I had a poster picture there. And let’s see what else. This is called “Ostrich Lake.” That’s on the cover of that book you got. I saw her bend over to tie her shoe and she looked like a [crosstalk 00:29:46].

Wynne: There’s the daisies see. You get a different view of things. This is an interracial picture called, “Grimms of Spring.” Bob Manry [00:29:56] titled this. He was on the picture desk that day.

Barrow: What about him?

Wynne: Bob [Manry 00:30:00]. Yeah, he named this “Grimms of Spring.”

Davis: So that ran in the Plain Dealer and what year were that of been Bill?

Wynne: That was just before … That was about ’61 or ’62.

Davis: And was that controversial at the time?

Wynne: No, because of children. I think the fact that it was children nobody said anything about it. But if they had been adults-

Davis: Cause what are those kids doing are they-

Wynne: They’re just … It was Feb. 4. They all come running out, throwing their coats in the air. It was 67 degrees. And they were throwing their coats in the air and they saw me with the camera and they all ran over. That’s a big take-my-picture-mister picture. That’s what it is, “Take my picture mister.” There they are – all interracial.

Wynne: It’ll be in there somewhere. There they are. You can see there’s Chinese. We got a couple of blacks. That Chinese boy here.

Barrow: They’re all reacting for the camera. They’re not just standing there-

Wynne: They’re all reacting to “Take my picture mister.” Let me see what else we got. Now these are my crash pictures.

Barrow: Your what pictures?

Wynne: These are the crashes of cubs at NASA. Now the program is to find the structure of the cub. And we gotta shoot it with camera. A fast [inaudible 00:31:33] 4,000 frames per second. So, you’re gonna slam this plane into the side of a hill at an angle because when a plane comes in like this- It comes down and hits at the wheel and a tip of the wing at the same time. It never comes in this way. It comes in this way. And so, we simulated that with the hill.

Wynne: So, I told them, “Wait a minute, I got an idea.” We’re not going to get enough light. They said, “Well, we’re gonna run the first one Bill. You can work on the other one.” OK, so what we did was I took and had focal plane bulbs would shoot one-tenth of a second duration. Now regular flash bulbs used to run at 50th of a second. And then once for focal plane shutters would be really slow, like a tenth of a second, I think.

Wynne: And then one at 250, that’s called a fast bulb before they had the strobe lights. So, anyhow what I did was I took … You couldn’t get the picture of the dummies. They had a dummy in there that we borrowed from Wright Field. The $45,000 dummy. He had accelerometers in his chest. And so, they could get the thing. And then we had a grid 4 inches apart, so we could get the movement against it.

Wynne: So, then we decided they need seatbelts. I don’t think they had shoulder harness. I don’t think we had shoulder harnesses yet. So, we put a shoulder harness and we had two dummies. One was a regular dummy that you just brought from a parachute. The other one was very expensive ones. So, he’s in the front. So now we got to illuminate. We don’t get any pictures from the first one because it’s too dark.

Wynne: So, I take all these flash bulbs. They’re 96. They’re gonna go off 24 at a time and I overlap the peaks like that. The peaks overlap. So, I got four bulbs going off. So there a shadow of this light on the dummy because if you throw one light you’re gonna get a heavy shadow. You might not be able to get the data. Two lights you’ll get two shadows. But with four lights, you get four very light shadows.

Barrow: Let me get this straight. I mean you can do with more with photography than just take your cellphone and aim it at something and push the button?

Wynne: I’m not even into that. Well, anyhow-

Barrow: The technical aspects of getting this is amazing.

Davis: I know.

Wynne: What we did this is we made a uterometer, a thing that would make a squeak in one second. So, no matter … Then we had the plane hit a switch 10 feet out from the barrier. And that started the flash bulbs. And it could start at any because they were sevens and 24s. They were four sections. So, no matter where that plane was at that point, flash bulbs will begin to shoot off and they just go in rotation. And they’re all over with in one second.

Barrow: I bet.

Wynne: And so … here’s the data. And this is where the camera timer here. This is the timer we needed for … And the timer, we could pan the cameras and track anything. We could make any little camera a precision instrument. This could make the … you take it down with our Mitchell camera, 124 frames a second supposedly. You’ll see the chart on that I did. That you will find that those particular … I forgot what I was gonna say. We’ll just move on to it. You’ll be getting over into this.

Wynne: Here’s the camera. It puts the time on film and this is the flash bulb [inaudible 00:35:21]. See it here? This all goes off in one second. All that data but they’re flashing, and they’re keeping that light. And boy, you should the beautiful picture that is. Those dummies are floating around. The one the head comes right off and bounces around in there.

Wynne: So, see we’re gonna slam it into the hill. And then-

Davis: This is for NASA?

Wynne: Yeah, I wasn’t a college graduate. I’m one of the two people in NASA’s history, I think that wasn’t a college graduate. [crosstalk 00:35:55] for them. The reason I left and go to the Plain Dealer. They couldn’t give me a raise because I wasn’t a college graduate. I didn’t have a degree that puts you out of professional level.

Davis: You’re sort of stuck.

Wynne: So yeah, I’m stuck. So, I get an offer from the Plain Dealer. I said, “Look, you’ve printed my pictures. I’ve also did a story that I sold them.” They threw a camera over the High Level Bridge on a tow rope and I took pictures on the way down. Suicide camera. And they ran it in the Sunday magazine. So, I was also … the color pictures of the crash fire program that he credited me with in the Plain Dealer.

Wynne: And I reached out to him one day and he says, “What are you doing?” I said, “Well, it’s Columbus Day. We got off and I’m just running around downtown.” He said, “Bill, would you consider working for us?” I says, “A newspaper?” And he said, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, you were nice. I got a family.” “Well, you won’t have to work nights. You can work days. Nine to five. We need a color man to be able to step right in and start doing color.” So, I started out-

Davis: And what year was this?

Wynne: 1953.

Davis: OK, so color was-

Wynne: Sunday magazine. Sunday Magazine was using color.

Davis: So, it was beginning to happen, but it was new.

Wynne: They were already had, Vern Cady was working in it. But they needed a helper and they also needed a photographer because Eddie [Solako 00:37:23] who was a great photographer, was working for the magazine and he got multiple sclerosis and they didn’t know what it was. Sterling Graham had to have him go to his doctor before being detected. It was very early in multiple sclerosis. So, they didn’t know how Eddie was going to come back to work.

Wynne: So, he worked for 22 years or more at the paper [crosstalk 00:37:48].

Davis: Now how long were you at the Plain Dealer?

Wynne: 31 years.

Davis: 31 years, wow.

Wynne: And then I went back to NASA. They called me, and I went back for four more years part-time.

Davis: OK, did they give you a raise?

Wynne: No not really because you are working for a contractor and I wasn’t doing that kind of work for them then. That’s Joey Maxim, [inaudible 00:38:14] you never were beating them.

Barrow: I remember going to this award ceremony when you got this journalism Hall of Fame Award. I remember Dave invited me to that.

Davis: Was that from the Press Club?

Wynne: That was the Press Club yeah. I got a plaque up at the Press Club. I’m in four halls of fame.

Davis: Yeah, I’m not surprised.

Wynne: Well, I’m not in the NASA one but I think that the present guy who’s the historian would probably like to have me in. But again, I don’t have a degree.

Davis: Have you ever thought about going to college? Going back?

Wynne: I came home from the war and I was working here, and we were coming in late flight and we were sick from the flights we were getting tossed all over the sky because they’re flying in ice. Everybody else is grounded. We’re flying through ice. So, you get kicked all over the sky and we’re all heaving and getting sick and wearing out parachutes. We didn’t know what’s going to happen.

Wynne: And so, then I had to go to Cleveland College at night to try to take a class and holy Christmas. So, I got to take remedial courses. I don’t take algebra in high school. I don’t take geometry in high school. I don’t take the language in high school. I would have to take all these remedial courses and I thought, “Geez, I’ve been through the goddamn war and I’m taking course in psychology.”

Davis: This is a lunchtime conversation with legendary Plain Dealer photographer, Wynne.

Wynne: So, we’re flying ice and what were we talking about there at that point?

Davis: Well, you were talking about not getting the degree and not [crosstalk 00:40:06]

Wynne: Oh yeah, not going to college.

Waitress: Everything going OK for you guys?

Davis: Yeah, thank you.

Wynne: And in the course of psychology they started to talk about conditioning of animals. And what am I taking this for? I did this with Smoky. So, I thought, “No point in me going and taking a course like this because …” I did finish the course. I passed it with a “D.” Due to my indifference and being sick half the time. But anyhow, that’s my story of my education. I was working with engineers. If I wanted to know something, I’d ask them to pull out the slide rule and give me the answer. They didn’t know what I was doing but they’d give me the answer.

Wynne: And if I absorbed a lot. Like Herb [Pinkle 00:41:03] one of the big research guys, a real terrific guy, says, “Bill learns by osmosis.” See I was working with college graduates at the Plain Dealer, most of them are college graduates now. But they all are now I think but, in those days, they were a mixture they had people they brought up as copy boys. Like Wilson Hearst Sheldon. Dale all of those were copy boys originally. You might have taken some courses in college.

Davis: This is a lunchtime conversation with legendary Plain Dealer photographer, Wynne.

Wynne: My comment is overall photographer was not very well understood by journalism, journalists. And it became an arm of support of an article. So, they didn’t really know how to hire people to head a situation like this so some of the heads of photographers are questionable. I don’t want to name names. I won’t name them then because [inaudible 00:42:31] because a good photographer [inaudible 00:42:35].

Wynne: He retires after 45 years and one of his boys was telling everybody, which is really bad, that he got the job because he used somebody else’s photos. You know what I mean? And [inaudible 00:42:54]. New York member [inaudible 00:42:59]. He was a writer. Graduated from John Carol but not a very good one apparently. They threw him in the photo lab. And then there was Dave [Warmilker 00:43:09]. He had a master’s degree in library sciences. He was a writer. He got in a big fight at the state desk with [crosstalk 00:43:21].

Wynne: He was a state desk earlier at that time. So, Dave had a fight and they threw him in the photo lab. And he was the most unhappy guy in photography I ever saw in my life. Finally, Chad [Orienciato 00:43:36] felt sorry for him and he took him out of the photo lab and having him writing obits. And he was happy to get out of the photo lab. And that’s the story.

Wynne: Now [Warmilker 00:43:49], the head of the Cleveland Public Library was [inaudible 00:43:52]. When did that? So, the way you pick photographer and the way they were in that … They were a miscast bunch of guys I’d ever seen. Ray Matjasic [00:44:09] was really good. He was a combat photographer in the Marines. He was a truck driver for the Plain Dealer and he fought his way to getting into photography and he did.

Wynne: He worked really hard for eight years and kind of sat back on his laurels after that. But he became chief photographer. And so, the brass on the upper level doesn’t understand the photography at all. They leave that go the way it’s been going for years and year. And what you end up with is a bunch of photographers that show something. They don’t say something.

Wynne: The mayor of Parma Heights said, “Bill makes his camera talk.” And that was a good definition. I didn’t realize it at the time. But the camera and it might have a purpose for having a picture. And we have so many pictures that don’t really have a purpose, like this thing. And they’re just coming out and blowing ones.

Wynne: But you don’t see pictures that say something, like the girls with arms around each other. The divers it looks like he a [inaudible] coming off the cross. The formation. I got one that I’m going to use is a fire plug. But it’s got an exhaust pipe that looks like a snake and it looks like a snake charmer in the middle. It’s in front of the Cleveland hotel. I come by and I see that.

Wynne: Well, I suppose that the cops come along and see this tail pipe in the street, picked it up and put it in the fire plug. Call the department and say, “Hey pick up this exhaust pipe. You can’t miss it. It’s by a fire plug in front of the Cleveland Hotel.” But it was standing up on end like a snake and it looked like a snake charmer with the fire plug. You know?

Wynne: Are you recording me? I guess he is. But the thing is they should … You have to be more discriminatory. Now Life Magazine, you remember Life they knew how to [inaudible 00:46:40]. They would take a guy with a third-grade education from Europe. If he could say something with the camera. They’d hire him. They had Juan Mealy and George [Stilt 00:46:55]. One was a graduate of MIT. So, they did the scientific type of pictures.

Wynne: But these other guys who had something to say with the camera. But particularly they were hired for that purpose. So that’s the story of how Life is. What happened with me was I went to New York with my portfolio one year. I think about ’56. And I was going to go to Black Star Picture Agency.

Barrow: Where?

Wynne: Black Star Picture Agency. They were big. I come into the office. I called for the day before. I come into the office with my portfolio and I was met by this chubby man with glasses. He looked like [inaudible 00:47:43] [Askoll 00:47:45] who was in the MGM movies. He was a comedian but an older man. And his jowls would roll when he laughed. But anyhow, this man comes to see me, and he says, “Oh you want to be a photographer?” And I says, “Yes.” “And so, we sit down, and we look at your portfolio.”

Wynne: He starts looking and “So tell me about yourself.” Well I started to tell him and he’s looking, and I had this photo essay [inaudible 00:48:15] right up front, the “Day Horses Cried.” So, I went to Jim [Madowitz’s 00:48:18] funeral. The first assignment I really did doing this.

Waitress: Guys can I get you anything?

Davis: Oh, I’m good thank you.

Wynne: In ’54 was March of ’54. And I saw the horses and they seemed to be in hooves and they were talking to each other. And I thought very sad standing alone. So I made a photo called, “The Day Horses Cried.” I said, “Today, Jim your friends gathered in your honor and you saw them like you had never seen him before. Some cried out such and such a way and others mourned silently alone. It seems Jim that your friends did not know in the ready room where policeman talk that they would be back the first day if there weren’t horses in heaven.” And that’s the way that ended it was just an essay.

Wynne: Well, he goes, “Oh, the horses they are crying at a funeral.” He starts to laugh and all the women at the office start to gather around. “Mr. [Madowitz 00:49:23] we never heard you laugh like this.” “This man he is a humorist with a camera. He takes [inaudible 00:49:35] and humor.” And he says, “I’ve been looking for 35 years for someone who could do this, and you got it all in your portfolio.” So, oh, he got so excited and I would say I was on cloud nine when I went back.

Wynne: What happened was, he wanted to put me on salary.

Barrow: What?

Wynne: Put me on salary. The thing I was doing. And he had a new partner who was an accountant, Howard Chapman. Howard comes in and he says, “Well, Bert I can’t see where he’s any better than the 30 guys we already have on salary.” So, it died there. But he was so disappointed. He wanted me to send him stuff. Well he was at the end of his life and he retired within six months or so and he died shortly after.

Wynne: But anyhow Curt [Churcransky 00:50:20] in 1934 had ran a magazine called [Derdane 00:50:30]. And he would use photos and not use any captions and they were juxtaposed. He might have two gorillas swinging from a tree and two nude women from the back in the water. And so, he would juxtapose these things. And so anyway, he brought in Alfred [Eisenstat 00:50:49] top Life Magazine photographer. He brought in about three or four.

Wynne: He was picture editor for the Life from the time it founded for 10 years. But then he founded this Black Star Agency and I caught him at the end. And he was looking for 35 years for someone … He said, “It’s all through your portfolio. The humor and the horses crying at the funeral and all that.”

Wynne: So anyway, I went home on cloud nine on the train. I never had to do anything with it. So, I went back to New York again the next year and I went to the biggest agency in the world at that time. It had Henry [Cardissan 00:51:29], Eugene Mills, it had three or four of the top guys in the world. About 10 men. So, I’m up there and there was this Swedish woman named Inga [Bondi 00:51:39].

Wynne: And I went in the office I showed them the portfolio and she was really impressed. So, she said, “I’ll have another man look at this but if you … We charge $1,000 to join us but after that you get paid, top pay.” So, I’m sitting there, and she gets a phone call from Chicago and it’s a photographer calling in. He’s only had another day shooting. She says to him, “Can you drop what you’re doing and go to New York. We need to get a job done in one day. You can go back and finish the job.”

Wynne: And I look around, I got nine kids. And I’m not gonna get on that … I already turned down show business for that. I could have traveled the whole circuit and made a lot of money but you’ve gotta take care of your kids. So, kids became the primary thing with me. And so, I turned down that job. But the Black Star thing would have worked out. But if the guy isn’t interested. Well, Howard because very, very knowledgeable over the years. He was very competent after that.

Wynne: But I had to catch him at the beginning, where he was thinking like an accountant instead of like an artist. But that wasn’t fate.

Barrow: Not making much headway here. We’re done. [crosstalk 00:53:02]

Wynne: You know what? I take these things home. Yeah, I do I only eat half of what I used to. There’s no end to this thing.

Barrow: Well, how old are you now?

Wynne: 95.

Barrow: 95. This is my model for being 95. I have no idea that I’m ever going to get anywhere close to it but if I do this is my model.

Wynne: Well, I don’t know. I’ll be 96 in March.

Davis: In March, oh it’s coming up. Wow, what day?

Wynne: The 29th. [inaudible 00:53:42] I’ll be [crosstalk 00:53:45]

Davis: Congratulations. You look great.

Wynne: My grandmother lived to be 99 and a half. And on mother’s side, my grandparents there both lived into their 90s. And my father lived to be 86. So my Aunt Pauline lived to be 97.

Barrow: You got the genes.

Wynne: I think that helps.

Barrow: As long as you’re not doing anything risky you know in your early life, like being in a war or something or hanging out in clam shell buckets-

Wynne: Or flying [crosstalk 00:54:24]. Luckily, we never lost anybody- [inaudible 00:54:32] They lost two or three test pilots.

Barrow: You think how many people never got to be 95 because they didn’t make it out of World War II.

Wynne: Oh, and how. That’s true.

Barrow: A lot of 20-somethings.

Wynne: I had a couple of narrow escapes. Like when a shell come over our head and I ducked underneath the Jeep with the dog. The dog leads me over the Jeep and I lie down next to her and hold my hand over her ears. The whole [inaudible 00:55:03] all the guns are going off and the kamikazes are coming in. So, a 20 mm shell shortfall passes 2 feet over my head and hits 12 feet away. All the guys standing up that I had been with, all got wounded because [inaudible 00:55:21]. And so, there was so much noise, I didn’t even know it was just another shell going off. And then I come out and there they were.

Wynne: And we had to take one kid. The one picture Smitty is on the left. Two days before the picture’s there it shows the Jeep tire that I laid alongside of. [inaudible 00:55:40] I had to take of the ship, he had a punctured lung. And they ran a barge alongside us. Ran a convey headed for Luzon. You don’t stop the convoy. He got hit like the one behind us. They hit 150 Air Corps guys there got killed in the ship right behind us.

Wynne: And so, has we’re going along, this barge has to come alongside us and load him into the barge while the ship was under [crosstalk 00:56:05]. So, they did it, but I had another one where they took me off the plane. [inaudible 00:56:13] why I was going to go along with Smoky. Everybody said, “Well, why did you take the dog on flights?” I was on a L5 flight. Flying over the Jap line. My first flight and that’s a canvas and wood plane, two men. And going along and as we were going over the section. We’re going over the Jap lines to find if a pilot had a chance to survive and I was going to take a picture to show the brass whether they should bring an infantry patrol through to try to save him.

Wynne: But as we’re flying along, we come to these holes in the ground and they got thatch strips like this about [inaudible 00:56:53] square on bamboo sticks and I look out and the pilots go, “You see those damn things down there?” I said, “Yeah.” “Those are Jap foxholes.” And I said, “Let’s get out of here.” I thought I was gonna get shot through the seat of the pants. We’re only 50 feet, and they got the engine idling going over these things.

Wynne: And he said, “Oh, you don’t have to worry about that.” I said, “No.” He said, “No, we threw grenades in those goddamn things yesterday.” They cleared it out the day before, that we could go over. And so, I came back and the guy’s gathered around. “Hey Wynne, what happened on your mission.” So, I told them. One guys said … Jack Cray said, “Hey Wynne, if you get knocked off, I can have Smoky, can’t I?”

Waitress: [crosstalk 00:57:35] No hurry.

Wynne: Can you make this for me to go?

Waitress: Yes, absolutely. As I figured, probably not hungry. I’ll box it up for you.

Wynne: OK and so, “Hey Wynne, if you get knocked off I can have Smoky.” And another guy said, “No, I want her.” Another guys said, “I want her.” I said, “The hell with you guys I’ll take the damn dog with me.” So, I took that poor little thing hanging in all the combat missions I was in. 12 combat mission.

Davis: 12 of them?

Wynne: Mm-hmm (affirmative). What happen was, they grounded up when the Luzon.

Barrow: Do you have any dessert stuff?

Waitress: I do what’s offered now. I have cheesecake, crème boule. We have an awesome upside-down apple pie comes with cinnamon ice cream. Hot apple pie. Lava cake.

Barrow: Did you say apple pie?

Waitress: Apple pie, it’s amazing. We have a chocolate lava cake with vanilla ice cream. We have a variety brownie. So, it’s like a reverse brownie. It’s vanilla, vanilla ice cream [crosstalk 00:58:26].

Barrow: I think I want the apple pie.

Waitress: All right.

Davis: I’ll have the one with chocolate cake and ice cream.

Waitress: The lava cake and apple pie. [crosstalk 00:58:34]

Davis: Bill, do you want some dessert?

Waitress: Do you want dessert? He’s like no. [crosstalk 00:58:40]

Barrow: He can’t have the cake.

Wynne: My mother’s [crosstalk 00:58:42]

Davis: But we’re not going to let you.

Barrow: You have to clean your plate before you-

Davis: We’re not going to let you eat but you have to eat before you have dessert.

Wynne: When I get on the first flight-

Davis: So, Smoky went on 12 combat missions?

Wynne: Right, she did. And it was only because I just didn’t know what was going to happen with her if anything happened to me. And I said, “If we go down, we’re going down together.” And then I knew she was good luck. But the first flight we were gonna go on. We’re at the mess hall 3 o’clock in the morning with the third Air Rescue Squadron. I’m going to fly with them. We’re going to pick up a crew of six guys in a life raft from a B-25.

Wynne: One guy gets killed on the plane landing in the water. Well, they’re in the life raft. So, we’re reading to go, and an officer comes to me and he says, “We’re gonna transfer you to another plane.” I said, “OK.” So, I went with the other plane. Well the plane I went with never returned. And so [inaudible 00:59:50] were flying with me he was a tech sergeant. We were all in the Navy. I’m a corporal. I can’t get a promotion because the TO is all filled up. In its headquarters, you can only have so many of this, this and this ranks.

Wynne: So, we kept getting people from the States coming in with getting ranked yet because they’d be in the army for a couple of years. And they come in with rank and they’re filling us with … And definitely make it impossible to get a raise. Anyhow, Switzer tells me about the plane disappearing and then about two weeks later or three weeks later, he tells me that they had a landing on [Ocasia 01:00:30] Island. And there’s a string about … 17,000 islands over in the Southwest Pacific theater.

Wynne: It’s just endless islands and they’re in groups and some of them are named and some of them are not. Some never seen a white man and some have never even seen a native. And they can go up and down too. You know how islands can appear and disappear. But any rate, he tells me that they have an invasion of an Infantry Patrol and they killed a cook a medic, a mechanic and a pilot and they burned the plane.

Wynne: They found the plane … It was a pontoon plane, a hiding back and a cove [01:01:10] and as the stragglers are coming back from invading … from bombing the Philippines. They lost a motor. They can’t keep up with formation [inaudible 01:01:19] But there’s plane. So that’s what happened to him. What happened was they replaced me with two other guys. One was a Navy lieutenant, was a radar specialist. Another one was a tech sergeant from another outfit and he was specialist in … one was radar and the other was radio.

Wynne: So, they already had radar and radio men in the booths. For some reason the government wanted these two guys to go. They never found a sign of anybody. The raft was gone. Nothing on them. The gat was gone and that was it. They went out searching for it. So that’s what happened. That was my first flight I was taken off. That’s when I say I had several close calls like that. That’s war I guess.

Barrow: Yeah well, they say there but for the grace of God.

Wynne: I went into the orderly room and I asked for a raise. “We can’t give it to you Bill. We can give you 10 days in Australia if you wanna.” I said, “Sure.” So, I went down to Australia.

Davis: This sounds like [crosstalk 01:02:32]

Wynne: So, I go down to Australia with Smoky. I don’t do anything. The first time I go down. I [inaudible 01:02:40] furlough I had Dengue Fever. And I take Smoky around to all of the hospitals. And she’s the first therapy dog on record. She started the whole therapy dog movement. She gets credit for this.

Wynne: So anyhow, down in Australia. We come back, and the squadron is grounded. And they were taking off the Air Force and we’re transferred. We’re going in the infantry to Luzon. We’re going to be the only photo squadron on Luzon. And we covered low level flights. We lost half our guys in that.

Barrow: You did what?

Wynne: We lost half of our men in that particular operation. Yeah. So, when they went to get back on flight status again. To fly with the third Air Rescue. I didn’t volunteer. No point in me going back to the States and being a corporal. Going to have to KP and all of the stuff that they did as a lower rate when I risked my life. Why go home early for that? So, I just never did. I waited out until the end of the war and I had my credits for 13 missions. And it would have been kinda stupid for me to go back at that kind of situation.

Wynne: Everybody else is coming back with a high rate. I’m going back as a corporal. Ah, it’s endless.

Davis: So, I was wondering Bill. I was gonna wait until Bill and I got our desserts. So, we could munch on them while we were making you tell more stories. But is there one at the Plain Dealer, a day or a photograph or a person or an event that sticks out more than others. I mean is there that one Plain Dealer memory that …

Wynne: Well, we were on the Sam Sheppard case. I worked that five times because I was working for the Sunday department features. The Sunday Department- I’d have 24 pictures in the paper. So that’s the Sam Sheppard case where he was accused of murdering his wife, Marilyn. So, we’re only there from November to July. That was July 4, that he did that. Night of July 5, the story broke.

Wynne: And I only covered it five times, but they were all very important. One, the mother killed herself. We all [inaudible 01:05:14] jail, where Sam was.

Davis: You say the mother killed herself?

Wynne: Yeah, the mother killed herself and the father died.

Davis: Her mother or-

Barrow: Marilyn’s mother.