Part One: The History and Culture of Poland by Judith Zielinski-Zak

The Social, Economic, and Political History of Poland

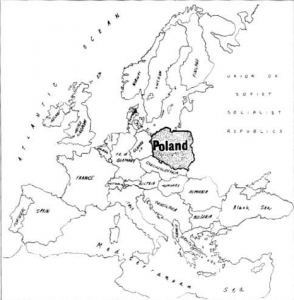

Poland has attained greater heights and suffered deeper humiliations than any other Eastern European country. As a nation they moved from a position of immense power in the Middle Ages to being literally wiped off the map for more than a century and a half during the eighteenth century. Yet despite continuous external and internal political strife, and devastating major wars, they survived–a credit to their perseverance and national pride. Witness to their present vitality is the fact that they now have the largest population and territory of all Eastern European countries.

Much of Polish tradition and national consciousness is rooted in geography. From very early times, Poles have resisted German pressure from the West and Russian expansion from the East. Yet Poland has adapted to a variety of foreign influences without losing a sense of ethnic unity. She has always considered herself to be the true center of Europe. She has zealously fought for and guarded her only access to the sea, through the Baltic. Often discussed as one reason for the many invasions of Poland is the flatness of the country, with its long Vistula river winding through the nation and flowing north into the Baltic. While the central plains are flat and open, there are also variations in the topography. Marshy flood plains abound near various rivers and a myriad of lakes fringed with reeds and swamps exist. There are forested areas and the Sudetan and Carpathian mountains form barriers to the south.

The Beginning of the Polish State: Piast and Jagiellon Dynasties

The Slavs settled in East Central Europe in approximately the sixth century and gradually became an agrarian people. The history of Poland as a unified state began with the settling of a branch of the Western Slavs, the Poles (meaning field-dwellers), between the Vistula and Warta rivers. In 966 Mieszko I, the fourth ruler of the Piast dynasty, married the Czech Princess Dubravka, converting himself and the entire nation to Roman Catholicism. This made Poland an East Central European country with a Western outlook. The reign of the first ruling dynasty of Poland, the house of Piast (native Pole), lasted from 966 to 1386.

Poland then consisted of a group of loosely connected provinces each under the suzerainty of a local noble. In 1226 Prince Konrad of Mazovia invited the Teutonic Knights, a Catholic crusading order, to help him convert pagan Lithuania and to help incorporate that country into his dukedom. More than extending aid, however, the Knights became firmly entrenched and effectively cut off Polish access to the Baltic for the ensuing 200 years. In 1386 the marriage of a Polish queen to Wladyslaw Jagiello, Duke of Lithuania, brought the two countries into a personal union. They fought the Knights and were victorious in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. The Teutonic Order never recovered its former power.

In response to the constant threat of Tartar raids in the 13th century, Germans were invited to colonize unoccupied areas and create a buffer zone. The conditions of colonization were favorable, especially in that the right of the colonists to live under German law was guaranteed.

By 1350, 1200 villages and 120 towns were under German law. The German colonization was attractive to Polish leaders not only from a need to repel invaders, but because the szlachta were being subject to increasing taxes. The Polish term szlachta may be translated as nobility, but it more properly means gentry. As a social class, they were the landowners, titled and privileged.

The Renaissance and The Reformation

The Renaissance entered Poland through Bohemia from Italy and was embraced with fervor by the court of King Sigismund August (1548-1572) and his Italian queen, Bona Sforza of Milanese nobility. In the first half of the sixteenth century, the Reformation spread to the major ports and especially Gdansk, a city with a large and prosperous German element. Both Lutheranism and Calvinism penetrated the upper classes. In fact, the traditionally Catholic gentry sometimes used the Reformation as an excuse to vent their frustrations and plunder the Church of its wealth and property. The Reformation spread with the growth of printing and the humanistic influence of the universities of Prague and Leipzig, where many Poles studied. On the other hand the famous Jagiellon University of Cracow, founded in 1364, fostered Catholicism and scholasticism in education. The Jesuit Order arrived in Poland in 1565 to initiate the Counter-Reformation and became firmly entrenched in Polish religious and political life.

Poland as a Republic

The period of an elected kingship began in 1572 and did not end until the last king, Stanislaus August Poniatowski, was elected in 1764. This system may sound curious to us, but there were precedents in Europe. Often these elected kings were not Polish at all. While some of these rulers, Stefan Batory of Hungary for one, were wise and able, the system led to a crisis of sovereignty. Besides this between the 16th and 18th centuries, Poland was frequently at war, fighting with the Swedes for Livonia and Pomerania in the seventeenth century, with Russia over her Eastern borders, and with Turkey over control of the Ukraine. She suffered greatly, losing precious manpower, financial strength, and for a time, her own independence. The great Northern War between Sweden and Russia brought havoc and ruin to Poland. Swedish, Saxon and Russian troops devastated much arable Polish land, and famine and pestilence followed.

King Jan Sobieski’s achievement in stopping the Turks at Vienna is a matter of historical pride for the Poles. But generally speaking, the European powers and even Sobieski’s own subjects did not truly appreciate the significance of the event. Many Poles resented the severe strain on their already exhausted country. King Sobieski died a sadly disillusioned man for his plans to establish a hereditary throne and to decrease the power of the gentry had failed. Peace with Turkey was concluded in 1699, but the price was high.

Stanislaus August Poniatowski, the last king of Poland, was an aristocrat inbued with the ideals of the Enlightenment. Although he was well educated, multilingual and a patron of the arts, he was a weak and vacillating monarch. Yet from the beginning of his reign in 1764, he gathered about him men of vision who worked desperately for needed social and political reform. One of these men was Hugo Kollataj (1750-1812).

Kollataj led the demand for a strong hereditary monarchy, universal taxation and abolition of the custom of the liberum veto. Although never a formal legal procedure, the liberum veto practice was unique and dangerous. If one member of the Diet voted against a proposal, it was not only defeated, but the negative vote could dissolve, or “explode,” the entire assembly. This meant any laws already passed in that same session were also null and void.

All the reformers were fighting against the weaknesses inherent in the system of elected kingship. Each election brought the threat of foreign pressure, and sometimes, force and bribery were used to elect a new king. Each new king had to agree formally to a Pacta Conventa, a contract between the king and his subjects. By the mid-eighteenth century, the rights of the gentry had grown disproportionately to those of other classes. Since some of the gentry commanded thousands of troops, this often meant that the king really had less power than his rich subjects.

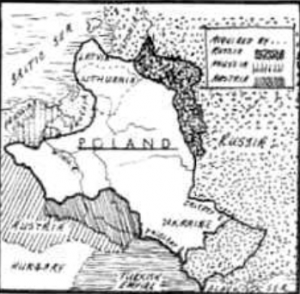

The Partition of Poland

By 1750 the Polish system of government had become a manifestation of individualism, supreme and uncontrolled. Lacking strong central authority, Poland was subject to the whims and capriciousness of its gentry. They perceived liberty as their own private property and never understood that force chokes liberty. Freedom was interpreted by the gentry to mean the right to choose kings, rather than the right to encourage a strong monarchy or to create truly representative government. Not all of the gentry, however, were selfish and politically naive. Some, like those who advised king Poniatowski, disagreed violently with their peers and tried to encourage reform. After the First Partition of the country by Russia, Prussia and Austria, a group of enlightened Poles led by Kollataj tried unceasingly to save their nation through the creation of the famous, albeit ill fated, constitution of the Third of May 1791.

Expressing many of the liberal and humanitarian principles found in the French and American constitutions, the constitution declared a hereditary monarchy and abolished the liberum veto. Russia was furious at the audacity of the Poles and declared war. It was brief, and in victory Russia partitioned Poland a second time (1793). A frightened Diet abolished the constitution and somberly accepted the Treaty of Partition. More land was taken from Poland. Though divided and defeated, Poland rose in a valiant revolt led by Tadeusz Kosziuszko. Educated in France, he sympathized with the French Revolution of 1789. Kosciuszko and his troops fought bravely but they were defeated at Maciejowice. The Third Partition that followed in 1795 obliterated Poland from the map of Europe. Kosciuszko’s life was spared, but he was imprisoned in Russia. While Poland as a political entity ceased to exist, her culture survived in the people, and the struggle for independence continued with renewed vigor.

Napoleonic Era

Many Poles looked to Napoleon for the restoration of the Polish state. The Polish Napoleonic Legion was founded in Italy in 1797. Under the command of Jan Henryk Dabrowski, Polish nationalism flared. The famous anthem, “Poland is Not Dead as Long as We are Living,” was written at that time. In 1798 the Poles helped the French to capture Rome. The Legion also fought in Santo Domingo in 1803 to crush a slave insurrection against the French. Those Poles who did not perish in that awful campaign died from fever and starvation. Napoleon recognized the bravery of the Polish cavalry, but his public statements rarely gave them credit. Yet Poles continued to believe that their efforts for Napoleon would restore their country. They fought for France because they thought they were fighting for the liberation of Poland. Napoleon could not have shattered the Polish dreams even if he had tried. To the people, the myth had become a reality. But some Poles did not trust Napoleon. Among these was Tadeusz Kosciuszko who recognized Napoleon for what he was: a political realist for whom France would always come first. However, few heeded his warning.

Bismarck’s Kulturkampf

Economic Pressures

Poland After World War I

Modern Poland

Since December, 1970, the leader of Poland has been Edward Gierek, who visited the United States in 1974. Closer cultural and economic ties have been fostered with America. Each year, more and more Americans visit Poland. Since its initial Year Abroad Program in 1970, the Kosciuszko Foundation of New York has increased its programs. American universities and other institutions are promoting similar educational programs or tours.