Main Body

Chapter 14: Sources on the Ottoman and Safavid Empires

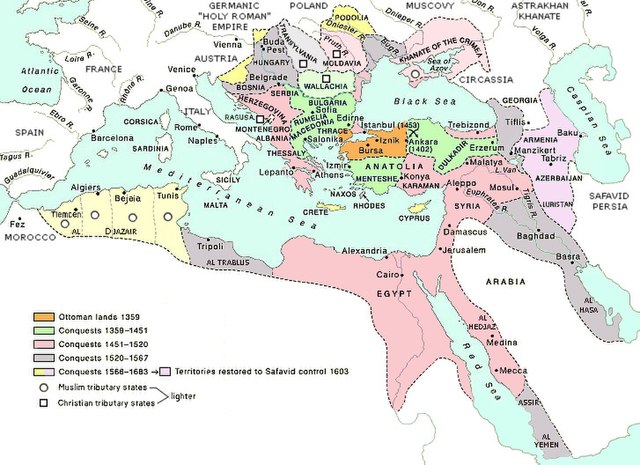

The Ottoman Empire first arose in the Western portion of the Anatolian peninsula in the late thirteenth century, following the Mongol conquests. The Mongols, and their successor Timur Leng, left a collection of local Turkish regimes in Anatolia that competed with one another for authority in the region. The regime that would eventually emerge out of this competition was a group known as the Osmanlis, named after the founder of the dynasty, Osman. In the early fourteenth century, Osman established an emirate based in the city of Sogut in northwestern Anatolia. From the very beginning, the Ottomans (as they would be called by Westerners) dealt extensively with Christians, and most of their earliest conquests came at the expense of the Christian Byzantine Empire.

In the following decades, the Ottomans would expand their territory to the European side of the Dardanelles, the long strait that separates Anatolia from southeast Europe. In fact, Ottoman power would be based as much on their possession of the Balkans as on any of their possessions in Anatolia. The earliest Ottoman sultans to establish their authority in Europe made alliances with Christian princes in the Balkans, but by the end of the fourteenth century, Ottoman sultans would simply conquer the Christian principalities and implement Ottoman rule. It was the Ottoman possession of the Balkans that allowed them to withstand a devastating defeat in Anatolia at the hands of Timur Leng in 1402. Not only did the Ottomans recover from this blow, but they had brought the rest of Anatolia, including the city of Constantinople, into their empire by the end of the fifteenth century.

The high point of Ottoman success is usually identified as being between the beginning of the reign of Mehmet II (the Conqueror) in 1451 through the end of the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent in 1566. The film “Islam: Empire of Faith, The Ottomans” talks extensively about this period in Ottoman history. During this time the Ottomans’ military recruitment system, the devshirme, through which they recruited Christian boys from the Balkans, converted them to Islam, and raised them up to be elite infantry troops, was paying rich dividends. In addition to Constantinople, the Ottomans conquered Syria, Egypt, North Africa, Iraq, Bosnia, Hungary and Transylvania.

The first reading linked below, entitled “Ottoman Conquest Documents,” chronicles some of the stunning conquests made by the Ottomans during this time. It includes an early account of Mehmed II’s conquest of Constantinople by a Greek writer named Kritovoulos. The second readings in the “Ottoman Conquest Documents” consists of correspondence between the Ottoman sultan Selim I and the Safavid ruler Shah Ismail in 1514 c.e., in the leadup to their consequential battle at Chaldiran. The Ottomans would deliver a devastating defeat to the Safavids at this battle, which halted their westward expansion and ended a series of conquests by Shah Ismail, who would never duplicate his previous successes following this defeat.

In fact, the Ottomans appeared to be an imminent threat to the European city of Vienna by the mid sixteenth century. The Austrian diplomat, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, who spent extended time in the Ottoman capital, drew grim conclusions regarding the future of Europe from observing the coordination and discipline of Ottoman troops. You can read some of Busbecq’s observations in the document linked below, entitled “Excerpts from The Turkish Letters by Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq.” A link to the complete translated text of The Turkish Letters can also be found below.

Excerpts from “The Turkish Letters” by Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq

“The Turkish Letters” – full text

The three documents linked below, entitled “Ottoman Sultanas,” “Smallpox vaccinations in Turkey,” and “Early Modern Europeans in the Middle East,” consist of several sources written by Western observers of the Ottoman and Safavid empires in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries. These documents include an excerpt written by the wife of a Genoese merchant (first document in “Ottoman Sultanas”), the text of an unratified treaty between the Ottomans and France (first document in “Early Modern Europeans in the Middle East”), observations made about Persia by the seventeenth century Anglo-French traveler, Sir John Chardin (second document in “Early Modern Europeans in the Middle East”), and two documents by the English traveler, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (second document in “Ottoman Sultanas” and “Smallpox vaccinations in Turkey”). At the time of Sir John’s visit, Persia was being ruled by the Safavid dynasty. An offshoot of a Turkish Sufi order, the Safavids eventually converted to Shi`a Islam. After uniting Persia under their authority in the early sixteenth century, the Safavids forcibly converted the Persian people to their form of Islam (Twelver Shi`ism), making themselves into a true ideological rival for the Sunni Ottomans.

Smallpox Vaccinations in Turkey

Early Modern Europeans in the Middle East

In contrast to observations by Europeans, Muslim documents from this period provide a different view of the Ottoman Empire. For example, the Syrian religious scholar Ibn Kannan was able to live a relatively prosperous and peaceful life in Damascus during the eighteenth century, as chronicled in the document linked below, entitled “Excerpts from A Damascus Diary, 1734-35.” In another Muslim document (also linked below), evidence of growing tensions between Muslims and the other monotheistic faiths can be seen in a fatwa issued by a Muslim scholar in Cairo, entitled “Islam and the Jews: the status of Jews and Christians in Muslim lands, 1772 CE.” These tensions were exacerbated by the expansion of European commerce into the Ottoman Empire, fueled by tax breaks granted by the Ottomans to foreign entities, known as Capitulations. The foreign businesses often hired local Ottoman subjects to represent them, and these representatives (usually Eastern Christians or Jews) received the same tax breaks as the businesses themselves. This situation created financial advantages, not available to local Muslims, for members of the minority faiths who were technically considered dhimmis subject to Muslim rule. It also led to resentments among the majority Muslims and increased religious tensions between members of the three Abrahamic faiths.

Excerpts from “A Damascus Diary” by Ibn Kannan

The Status of Jews and Christians in Muslim Lands

There is no question that the Ottoman Empire ranks among the great empires in the history of the world. At its height, it managed to rule over such contested areas as Iraq, Palestine and the Balkans with a minimum of trouble. The fall of the empire in the aftermath of World War I created turmoil in the Middle East that the region has yet to recover from. Your challenge this week is to learn about this great empire and its impact upon the history of the Middle East.

Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, Turkey

Take a free 360 degree photographic tour of Topkapi Palace! Stunningly beautiful! Click and drag to pan around the photographs. Click on the arrows to move from room to room.

https://360stories.com/turkey/point/topkapi-palace-museum?mode=2&playerMode=2

See another Virtual Tour of Topkapi Palace with an overhead map of the layout.

Hagia Sophia, the Great Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey