Main Body

The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Painting: The Nineteenth Century

In reaction to the Rococo style, a new artistic movement was born in Europe. Its name is derived from the Latin classicus – the excellent, the outstanding. Although the basis for it had been laid in the artistic colonies of 17th century Rome, its period dates have been established as 1760-1830.

In Europe, this was an era of the rationalistic philosophy, of the French Encyclopaedists; in art theory, that was a period in which revival of classical forms were considered the ideal of beauty. There was a general quest for harmony, seriousness, and tranquility. Compositions were balanced, drawing was firm and clear, modeling had relief qualities, coloring was restrained, and subject matter favored classical themes.

Taken altogether, these ideals may have exceeded an artist’s ability to assimilate – especially those which broke from the strong traditions of the past. Perhaps these ideals were too lofty to be acceptable to the society of Serbs living outside Turkish domination. However, aspects of this style were imported to Vojvodina, and were adapted to the specific needs of the new society.

Painting, which dominated this movement among the Serbs, emerged under its own and very specific national form.

Classicism as an art movement appeared among the Serbs living in Vojvodina only slightly after it rose in Western Europe. Scholars have designated the years between 1790-1848 as the duration period of this style. The classicistic style, based on strong drawing and firm modeling, rather cool and restrained coloristic spectrum, was propagated among Serbian artists through the Viennese Academy, led by the painters H.F. Fuger and P. Kraft. The engravings also served as an important intermediary, bringing new themes before the public eye.

The oldest and the leading exponent of the new style is considered to have been Arsen Teodorovic (1767-1826) who also studied painting in the Viennese Academy. A prolific painter of iconostases, which must have offered very lucrative commissions to artists, he created over fifteen large ensembles for Futog, Vrsac, Sremski Karlovci, Sremska Mitrovica and others. He also left a significant number of portraits, including such formal works as the portrait of “Bishop Kiril Zivkovic,” who stands in full ecclesiastical regalia; and many others. Among these are: “Portrait of Dositej Obradovic,” a famous Serbian writer and one of the first modern educators; portrait of a “Young Man in Blue;” and a “Portrait of an Unknown Lady.” To this list can be added many others of the lesser nobility and the wealthy artistic clientele of South Hungary. The backgrounds are most often left simple and neutral, without details of architecture, draperies, and the like, and are only gently illuminated. Therefore, this able draftsman concentrated on the sitter, using details of the garment as the elements subordinate to the figure, which have a strong sense of monumentality.

The artistic career of another Serbian classicist, Jovan Stajic-Toskovit, was interesting though brief (1799-1824). He painted compositions with the classical themes, such as the “Ceres” and “Jupiter and Hera,” which are not frequently found in this new Serbian society. There are a number of painters who work in the neo-Classical style during the first half of the 19th century and even later, who satisfied the demands of the Church (paintings of the iconostases and portraits of the high clergy), and above all, the demands of the fast-developing bourgeoisie.

One of the more prolific and accomplished artists was Pavel Djurkovic (1772-1830). He was schooled outside the Viennese circle. Djurkovic worked for the Hungarian Palatine as court painter. He, too, was engaged in painting iconostases (Vrsac, Sombor, and others), although he is better known through his portraits of outstanding Serbs. Among his subjects were “Vuk Karadzlc,” a famous Serbian linguist and reformer, and his wife “Ana Karadzic;” “Milos Obrenovic,” Prince of the newly formed Serbian State; “Atanasije Stojkovic;” members of church hierarchy (“Lukijan Musicki;” “Metropolitan Stratimorovic”); and the new and important class of educators in gymnasiums (“Principal Gercic”). A competent painter, Pavel Djurkovic excelled in his depiction of texture and details. His main strength lay in his ability to convey the psychological expression of his subjects; otherwise, he painted with clarity of style and with strong, sculptural modeling.

The second generation of the neo-classical painters entered a new stylistic phase, characterized by sentimentality. It stemmed from the taste of the new bourgeois society and covered the period from approximately 1815 to 1848. The usual name given to this style in German and Central European countries is Biedermeier.

One of the first exponents of this style working among the Serbs was Constantin Danil (1789-1873). Born in Lugos, he studied in Temisvar under Arsen Teodorovic about 1816 , and further worked with a number of painters-teachers (Nessenthaler, J. Bayer for the historical composition, J. Volk for portraits) in the same city. After 1820 his activities cannot be followed precisely, but we know that he visited both Vienna and Munich. By 1827 he married and v settled in Veliki Beckerek; frbm there he traveled through the Pannonian plains, painting iconostases, many portraits, and one remarkable still-life.

Among his religious works, scholars consider the iconostasis for the Uspenska Church in Pancevo the most outstanding work of -this genre (1829-1833). Others show the same relative level of artistry, but do not reach the heights of greatness (iconostasis for the Romanian church in Uzdin; iconostasis for the Serbian church in Temisvar, 1827-1843; and others such as in Dobrica Village, Jarkovac Village).

Among his early portraits one notes the impressive “Prota v Pavle Kengelac” in Pancevo, 1829-1831, in which delicately toned flesh is contrasted with a brilliantly painted jewelled cross, and dark priestly robes. In this example he balances classical stylization in drawing with a much freer application of color. In his later works he uses lazur, and a generally much lighter pallette. He continues with careful modeling, and pays a great deal of attention to the decorative elements on the portraits (“An Austrian Official ,” Senta; “P. Nikolic – Temisvarac,” in Belgrade; “The Lady in Blue,” Senta). The portrait of “Member of the Kranjcevic Family” in Pancevo is a vertical oval, and the subject is depicted wearing a classical toga with his right shoulder bare. “A Citizen of Beckerek” (in Senta), is represented in whole figure, seated in the interior of his home, before a background of monumental columns and folded draperies – themes that appear in early 20th century photographic portraits. In the portrait of the “Painter’s Wife” (Senta), the lady is seated, and in three-quarter view. Her head is turned to the observer’s left, as light plays upon her face, eyes, soft hair, and clothing. Although the paint is applied rather freely, sentimentality is almost overwhelming. The same feeling pervades his “Flora” with a garland of flowers (Belgrade, National Museum).

Danil’s only still-life (Belgrade, National Museum), is among his better attempts at representing the watermelons, grapes, and other fruits so abundantly produced in the gently rolling and fertile lands of his countryside.

In the works of Constantin Danil one can follow his progress and digression as an artist. His talent seems to have been considerable, although insufficiently developed. His weak points were in drawing, and he possessed almost no sense for organized and balanced composition. In the execution of the illusion of depth he is not absolutely convincing, yet his early works show a good sense for nuanced tonality of color, which in time, grew too light and cold, and too monochromatic. In technique Danil was completely dominated by the Vienna style. Danil traveled to Italy on two occasions, in 1846 and 1857, although by artistic temperament he had no natural affinities with Italian painters and was rather more attracted by Dutch masters of the 17th century – an interest exhibited in his own brilliantly worked textures and surfaces.

Constantin Danil had several students, the most outstanding of whom was the protagonist of the Serbian Romanticism in painting, Djura Jaksic.

Danil’s somewhat younger contemporary was Nikola Aleksic, who studied first with Arse Teodorovic and in Vienna. His opus consists v of much the same type of work on iconostases (Mali Beckerek, Mol, Stara Kanjita, Arad, Gospodjinci and others), and portraits, e.g., “The Artist’s Children,” and several historical compositions. His talent was similar to that of Danil, but he was more productive.

Until the 20th century, the women played minor roles in the history of visual arts among the Serbs. We have mentioned Jefimija, who in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, made a small contribution. Our next candidate for study was a Serbian woman of the 19th century.

Born to the family of a building contractor, Katarina Ivanovic (1811?-1882), showed early signs of artistic ability. Such talent was not only recognized, but appreciated in her small town of Stoni Belgrade where she found an understanding merchant sponsor (Dj. Stankovic). Because of him she was sent to study painting in Budapest under a professor of Czech origin, a certain J. Perskyj. One of her early works from that period drew the attention of a Hungarian noblewoman and philanthropist, Baroness Csaky, who further helped Ivanovic reach Vienna. Since in 1835 no women were admitted to the Vienna Academy of Art, Katarina Ivanovic was not accepted on a regular basis, but she entered this institution as a special student. From the last years of that decade she left one of her “Self-Portraits,” and from 1840, the portrait of a Serbian writer, with whom she formed a long friendship. The painting was entitled “Sima-Milutinovic-Sarajlija” and this writer dedicated one of his literary works to her. So far this young Biedermeier painter accepted and worked in the usual themes of the period. But portraiture did not remain her only interest. In 1840 she produced one of her still-lifes, “The Grapes,” a subject to which she was to return several times during her career.

After Vienna, Katarina Ivanovic was among the early Serbian artists who made the pilgrimage to Munich, where she widened her scope of interest by painting a “Bavarian Landscape,” and genre scenes – “The Return from the Procession” and “Death of a Poor Woman.” Later, in 1842, her artistic voyages took her to Paris and Italy where she produced the striking “Vineyard Worker” in which she combined figure and still-life.

The year 1846 found her in Belgrade, a fast-developing town and new center of free Serbia; hence, it was a focal point of cultural and artistic life among the Serbs. Although Katarina Ivanovic stayed there for less than two years, she tried her hand at another first in modern Serbian painting. This time she undertook to paint, in the style of a sentimental classicist, an event from the recent Serbian past – “Karadjordje Taking Belgrade in 1806.” During her stay in Belgrade, she finished a number of portraits, including two of “Persida Karadjordjevic,” “Portrait of the Wife of Sima-Milutinovic-Sarajilija,” “The Dimitrije-Hadzi-Rose and His Wife,” “Uzun Mirko Apostolovic,” and numbers of children’s portraits (“Young Danic,” “The Stanisic Children,” and others).

Ivanovic remained true to her established repertoire by painting still-life and some historical compositions, which, unfortunately, were less successful. The latter dealt with Serbian and Byzantine pasts as if heralding the Romantic era in painting (“Death of Serbian King Milan;” “Betrothed of Olivera-Mara;” “Serbian Queen Jelena;” and “The Patriarch of Constantinople Condemns the Wealth of the Court.” Among her genre theme, the painting of the “Old Woman at the Meal” has been praised, while some others from that series are considered less accomplished (“The Return,” “The Love Letter,” “Death of a Wealthy Woman,” and finally, the “Artist in Her Studio”).

Katarina Ivanovic was fully an artist of her generation, period and style in addition to being an accomplished draftswoman and colorist (“Self-Portrait” – National Museum, Belgrade).

Her very special interest in furthering the national art collection in the new Serbian capital of Belgrade was supported by two personal donations to the Belgrade Museum, and the gift of a considerable number of her paintings. For these and other services, she was elected to membership in the Srpsko Uceno Drustvo (Serbian Learned Society) – the nucleus of the future Serbian Academy of Science.

Several other painters of this phase of classicistic art brought their own individual distinctions to this era: the works of Jovan Popovic (1810-1864) have been highly evaluated by scholars, who regarded him as the best Serbian portraitist; Uros Knezevic (1811-1868) was the most prodigious in artistic output. As the last Serbian representative of the neo-classical movement, Dimitrije Abramovic (1815-1855) can be cited. He started his artistic education in Novi Sad, to be followed by the usual route to Vienna, from 1836. There he studied with L. Kupelweisser, and privately with F. Amerling. Like Katarina Ivanovic, he came just to work in Belgrade, but remained much longer (1841-1849), continuing to paint not only Serbian notables of that period (“Knez Mihajlo,” “Vuk Karadzic,” “Joakim Vujic,” and others), but also religious subjects (iconostasis of the Cathedral of Belgrade, 1841-1845; iconostasis in the Church of Topola, etc.). In his stock of neoclassical themes, Abramovic made adjustments to include Serbian literary figures. To this category belongs the “Apotheosis of Lukijan Musicki” (1838) – the great Serbian writer from Vojvodina. The foreground is elevated, the hills disappear into the distance of an idealized landscape. On the right is the arched opening of the author’s tomb, into which he is led by the Angel of Death. Musicki turns his head in profile (reminiscent of the laureled head of a mature deity) toward the accompanying winged Angel-Muse who is carrying a lyre. Traces of the Nazarean influence are suggested; the warming up of his color scheme foreshadowing Romanticism.

Abramovic not only learned about the neo-Classical style in Vienna, but was also introduced to classicistic art theory. While in Belgrade, he painted and also participated actively in the cultural life of that city: he published critiques, drew caricatures, urged the formation of an art academy, and took a keen interest in mediaeval monuments, especially those of Athos.

There were other, minor, painters who belonged to the neoClassical movement, while still adhering to national traditions (the members of the so-called “Valjevo School”). Unfortunately, the scope of this survey is too brief to permit discussion of them.

Artists of the neo-Classical movement shared more than technical. affinities. Better trained than previous generations, they left provincial Temisvar and Budapest for the cosmopolitan centers. Not all of them went to Vienna; some reached Italy (C. Danil, N. Aleksic, K. Ivanovic), and beyond, to Germany and France (Katarina Ivanovic). While religious art figured prominently, together with portraiture, in works of this style, neo-Classicists were also attracted to still-life, genre, and compositions inspired by mythology or national history.

However, with no national center in Serbian lands owing to the Turkish conquest, the production of grandiose national and heroic themes was rare. Later, some artists living under the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy found their way to Belgrade, which, newly freed from Turkish domination, fast became the focal point for every aspect of Serbian life.

In summation, the artists of the neo-Classical movement had partially broken with tradition by moving toward Western European models, thus considerably narrowing the gap between late 18th to middle 19th century Serbian art and the arts of the neighboring states.

While Classicism in Western Europe was reaching its high point, the seeds of a new style had begun to germinate by the end of the 18th century. This style came to be known as Romanticism – a word of French origin, first applied to describe picturesque English landscapes. By the beginning of the 19th century it had acquired a broader meaning, and was applied to many and various art manifestations. Among those, Romanticism is perhaps best defined in literature and painting.

The aesthetic theory of Romanticism grew from the new, strong, rich and sentimental middle class. Generally speaking, this theory is a complex and ambiguous association of diverse elements. Above all, this movement was defined as anti-Classical and anti-rational. And, like most movements, its adherents considered themselves unique, progressive, and unbound by convention. Thus, where reason was previously exercised, Romantic artists employed imagination; and, instead of restraint, they practiced sentimental emotionalism. Whereas the neo-Classicists built their aesthetic values upon clearly defined forms, dominated by drawings that convey idealized beauty, Romantics sought their idioms elsewhere. Romanticism tried to express honestly and directly human sensibilities, to convey expression and the excitement of inner life through freer composition, “emotional” coloring, and an abundance of lights and shadows. To brighten pigments, bitumen was used, although in time colors darkened and denied in the end the very attribute of brightness which the Romantic works sought to emphasize. Boldness of expression was advocated and carried out by the use of aquarelle and other techniques such as copper-plate engraving, wood-cuts, and lithography.

Romanticists made no distinctions between themes; all were considered of equal value, as long as painting evoked the moody aspects of nature, life, or inner feelings. Feeling and imagination, then, dominated the infant stages of Romantic painting, though such attitudes were joined by others which expressed interest in utopian, oriental, mediaeval, mystical, and sentimental motifs.

In Serbia, the Romantic movement was enthusiastically supported. By making Serbs more aware of the importance of national tradition, historical past, and the wealth of national poetry, Romanticism raised national consciousness. In Vojvodina the Romantic period flourished between 1848 and 1878. It is interesting to note in this connection that many of its characteristic elements were already present in earlier Serbian neo-Classicism. General bourgeois sentimentality had been characteristic of the whole Biedermeier period. Katarina Ivanovic had painted nationalistic themes (“Karadjordje Taking Belgrade in 1806;” “Betrothal of Olivera-Mara;” and others). Uros Knezevic expressed Romantic feeling in the portraits of the heroes of the First Serbian Revolution, while G. Bakalovic followed suit (e.g., portrait of “Knez Ivo od Semberija”). Another woman painter, Mina Vukomanovic (1828-1894), daughter of Vuk Karadzic, though inferior to the others, painted Romantic portraits of Montenegrians, and such themes as “A Girl With the Grape Wine.” D. Abramovic’s portrait of “Vuk Karadtic” is considered a truly Romantic work, in spite of this artist’s neo-Classical orientation.

The transitional period between Classicism and Romanticism can be seen in the works of two Serbians, trained in the classical style in Vienna, but who embraced many Romantic concepts. Thus, their works include portraits, iconostases, and Romantic subjects. Jovan Klajic (1815-1883) expressed that sentiment in his religious compositions – “The Judgment of Solomon;” and “David With the Harp” – while among his iconostases one can cite the following: in St. John’s Church, in Novi Sad; in Kuzmin; Stari Vrbas – all in the 1850 ‘s, with some others from the next decade. The influence of Nazarene art is felt beyond any doubt. On the other hand, Pavle Simic (1818-1876) painted, also under the Nazarene influence, compov v. sitions inspired by Serbian history, such as “Hadzi-Djera and Hadzi-Ruvim,” “Surrendering the Harac (Turkish word for Itaxes ‘ ) by Ilija Bircanin,” from 1851-1852. His activity in iconostasis painting extended over a period of twenty-five years, and included y works in Kuvezdin, Sabac, Senta, Novi Sad (St. Nicholas Church), Sombor (the cathedral), Zemun (Haris chapel), and others.

Novak Radonic (1826-1890) is considered to be the first truly Serbian Romanticist. His artistic education began in the studio of Petar Pilie in Senta. In 1850 Radonic worked in Arad with Nikola Aleksic, the noted Biedermeier painter. Later, in 1851-1856 he studied at the Academy of Vienna with K. Rahl. The following two , years spent in Novi Sad mark the high point of his career as a painter, which he later neglected in favor of a literary effort. His surviving opus consisted of a number of drawings and copies of Old Masters from the museums of Vienna and Italy, and a small number of portraits. Radonic left two iconostases in Srbobran and Ada, one unfinished in Ilandza, and a landscape of “Hopovo Monastery.” In portraiture, Radonic is at his best (“‘Young Dusan Popovic;” and “Young Monk,” both in Belgrade, National Museum). He also painted Romantic “portraits” of the national historical figures from the Middle Ages, such as “Tzar Dusan,” “Strahinjic Bane,” “Kraljevic Marko.” Among his most Romantic works are compositions inspired by themes from Serbian history, such as “Death of Tzar Uros,” or “Death of Kraljevic Marko.” Another Romantic composition is a variation on the apotheosis theme “Ville Crowning Branko” (the fairies from Serbian epic poetry crowning a Romantic poet, Branko Raditevic). Radonic also left self-portraits in oil and pencil. Good drawing, monumentality and skilled modeling distinguish his painting.

Djura Jaksic (1832-1878) is regarded by some authorities as a master of most remarkable artistic temperament, and by many others as the greatest Serbian painter of his time. Born in Vojvodina, in the province of Banat, in 1846 he attended drawing classes in Temisvar where he was instructed by Dunaiski. A year later, this able young man moved to Budapest to study with G. Marastoni, a Biedermeier-style painter. Jaksic’s Romantic inclinations first manifested themselves here in his choice of subjects, apparently entirely drawn from the works of Shakespeare and Byron. This affinity to the poets and poetry is easily comprehended, since Djura Jaksic himself was an outstanding Serbian poet.

Politics also had its attractions and consequent disadvantages. In 1848, after participating in the Hungarian revolution, uaksic had to go into exile in the city of Belgrade. A now lost composition from that period recorded a revolutionary event: “The Fall of Sentoma;” In Belgrade, Jaksic became a simple laborer, but in 1850 he went back to painting. This time it was with Constantin Danil in Beliki BeCkerek (now Zrenjanin). At this point in his, evolution as a painter a few inconsequential icons and portraits are attributed to him.

In 1851-1853 Jaksic busied himself copying Old Masters in the Museum of Art, Vienna. Through N. Radonic and S. Todorovic, he kept in touch with Austrian Romantic painter, K. Rahl. About 1853 he returned briefly to Serbia, and then traveled to Munich, where he continued to study Old Masters. About this time, he reached artistic maturity, which is evident in two portraits completed on his return to Vojvodina – “Knez and Kneginja from Srpska Crnja.” The artist himself must have felt secure about his skill since, in 1856, he opened a workshop in Kikinda. Though the venture was not financially successful, paintings from this period are regarded as early masterpieces: “The Girl with the Lute;” and, above all, the coloristically bold “Girl in Blue” (National Museum, Belgrade). A religious composition, the “Sacrifice of Abraham,” is also preserved from this period.

Leaving Kikinda for Novi Sad, Jaksic started painting historical personages (“Tzar Dusan,” “Knez Lazar,” “Kraljevic Marko”), or personalities lionized in national epic poetry (“Banovic Strahinja”). In 1857, Jaksic moved back to Serbia which he made his permanent home. Unsuccessful at earning his living by painting, he took a position teaching in provincial Serbia. Not many compositions come down from ‘ that period (“Torches at the Stanbul Kapija,” 1859, is attributed by some scholars to this period). After some time teaching in Potarevac, Jaksic returned briefly to Vienna (1861-1862) and studied at the Academy with C. Wurzinger. Several excellent works emerge from his second Viennese contact (“The Gifts of Bajazid;” “Heroic Death”). The “Death of Karadjordje,” 1862 (Belgrade, National Museum) is dramatic, and extremely cognizant of light and dark areas – lessons remembered from Rembrandt. Among the compositions of the period following his stay at the Academy, and while he was again a teacher in provincial Serbia is “The Insurrection at Takovo” (1864) – a dramatic moment depicting the choosing of the leader for the Second Serbian Revolution. Jaksic skillfully contrasts the powerful figure of Prince Milos with some men, and a single woman with child. The national banner is seen against the massive trunk of an ancient tree, behind which mountains 100m ominously. Around 1868-1869, he painted “The Child on the Bier,” and “Knez Mihajlo on the Bier.” Before moving to Belgrade in 1872, Jaksic finished a number of portraits (“The School Teacher Katarina Protic,” “Director Ciric,” and “Major Varjacic,” etc.), in which intense colors and arresting situations compel our undivided attention.

The last period in his life began with his move to Belgrade, where he became director of the State printing press. Lastly, one must cite the portraits of “Djordje Ivanovic-Masadtija,” “Milovan Ristic,” “Young Knez Milan,” and the composition “Night Watch” (1876) in which the artist returns dramatically and Romantically to capture the expression of the midnight guard whose faces are illuminated by firelight.

Temperamentally akin to Jaksic, Stevan Todorovic (1832-1925) studied at the Academy in Vienna (1850-1853) and in Munich; he traveled twice to Italy and spent a short time in Paris. Serbian artists started looking for the artistic horizons far beyond Vienna. In 1857 Todorovic made Belgrade his permanent home. There he opened a drawing school, and later taught this subject in gymnasiums (high schools). This prolific artist continued the old tradition of painting iconostases (e.g., those from the Ascensioh Church and the church in Toptider, both in Belgrade, and others). His portraits are valuable aspects of his art, since he not only created a whole gallery of Serbs from the second half of the 19th century, but rendered them in an inspired manner, with broad and free brush strokes, and rich, warm colors. The portraits of “Djordje Maletic” and “Kornelije Stankovic,” and those of “Knjeginja Julija Obrenovic,” “Kapetan Misa Anastasijevic” and two “Self-Portraits” are regarded as his best. Several of his works in this genre represent the last phase of Serbian Romanticism (e.g., “Portrait of Dimitrije Posnikovic”), while in later works S. Todorovic exhibits signs of a transition to realistic themes.

His opus was not limited to religious works and portraits. Like his fellow Romanticists, he painted landscapes (e.g., “Manasija Monastery” 1857), historical composition inspired by Serbia’s Mediaeval past (“St. Sava Taking Monastic Vows;” “Building of the Manasija Monastery”), and events based on 19th century Serbian insurrections against the Turks (“Death of Hajduk Veljko”). His travels through Turkey and Asia Minor are examples of genre paintings (“Artist and His Family on Bosphorus”) – truly imbued with Romantic feelings.

The succeeding art movement – that of Realism – commenced in the middle of the 19th century, and primarily manifested itself in painting and graphics, less sculpture and architecture. Realism also broke ground in circumstances which produced the industrial revolution and the growth of natural sciences. It was less a philosophical movement than a practical belief (critical or naive) in the existence of an external environment independent of our thoughts, as a reaction against Romanticism and “art for art’s sake” of the Second Empire. Originating in France, Realism made its appearance in Germany a decade later. In most other countries, Realism more often manifested itself in the formal aspects of painting rather than in ideology.

In the Realistic movement, many artistic understandings were adopted, but none dominated. For the Realistic painter, since the technique was rather important, he drew inspiration from past masters (Dutch, Spanish, French painters of the 17th century). Some works do have social context, although they were not absolutely required; other artists dealt with moral or contemporary themes.

Basically, Realism tried to oppose idealism in art, and to depict the world as it was, without artistic embellishment. It attempted to create an art for the people (Daumier, Courbet, Millet), an expression of the world, firm and convincing, but without detailed description. This movement marked a transitional period between Romanticism and Impressionism, and served as the artistic base for other modes of expression, e.g., academic realism, socialist realism, surrealism, etc.

Realism in art was a movement that did not find a strong supportive basis in underdeveloped and agrarian Serbia of the last quarter of the 19th century. Consequently, Realism was short-lived, lasting barely two decades before giving way to other movements. Manifesting itself first in the late portraiture of S. Todorovic, mature realism was only attained with the appearance of Milos Tenkovic (1849-1890). He first started as the student of S. Todorovic, then moved to the Academy of the Applied Arts in Vienna, and from there to the Academy in Munich (1872-1878). Works from that period were shown at an exhibition in Belgrade in 1881.

M. Tenkovic died young, and very little remains of his artistic output: some sketches and aquarelles, one unfinished portrait, and three other genre paintings (“Landscape with Cows,” “The Flower Vendor,” and “A Still-Life with Majolica”). He showed a masterly command of technique, and faithful adherence to Realistic methods.

Two other Serbs, Antonije Kovacevic (1848-1883) and Djordje Milovanovic (1850-1919), followed in Tenkovic’s footsteps, but left too few paintings to be included here.

Instead, Djordje Krstic (1851-1907) must bear the entire burden of artistic witness for his generation of Serbian realists. Krstic also studied in Munich, with a stipend provided by Serbian Prince Milan Obrenovic, from 1873-1881. Not all of this time was spent in Germany, for he made study trips through Serbian lands. He left behind a large amount of works, perhaps too diversified in theme and technique, but which are judged by scholars to be of the highest artistic order. His approach is predominantly rational, and occasionally sentimental, regardless of subject matter (“The Drowned Woman”), but always impressive in coloristic solutions, and thick pigments.

First of all, this artist left a great number of sketches of Serbian national costumes and landscapes; a number of landscapes, of such as “Cacak,” “Zica,” “Path in Kosutnjak,” and especially magnificent renderings of “Kosovo” and “Babkaj.” Among his interiors are “The Narthex of Studenica,” and “By the Fireplace.” His folkloric themes include: “Departure,” “Under the Apple Tree;” while the genre is represented by the “Fisherman’s Doorway;” and the still-life is represented by “Still-Life with Watermelon;” and “The Fall of Stalat” illustrates his work on historical composition. One of his figurative scenes, that of the “Anathomli” (Belgrade, National Museum), is considered one of his masterpieces: the bearded, pensive scholar is seated in an interior, surrounded by the symbols of his scientific pursuits. In this painting, it is the face, above all things, which draws the observer’s attention. Krstic also left several iconostases in which he more or less successfully mixes Realistic methods with religious sentimentality ” (Curug; Stari Adzibegovac, Nis, and Lozovik).

The next stage in the evolution of Serbian painting is marked by so-called Academic Realism, which was dominated by Uros Predic (1857-1953) and Paja Jovahovic (1859-1957). Both enjoyed long years and thus outlived by far their own style. Both were talented, capable, and productive artists, who seem to have chosen to remain as Academic Realists, letting other, younger, artists join the more modern movements. In doing so, they were able to show off their superior mastery of drawing and colors. Although for these reasons their art is occasionally spellbinding, it can be overwhelming in its sentimentality.

Uros Predic was one of the most outstanding students in the Academy in Vienna, where he worked for a time as an assistant. Upon his return to Belgrade, much of his talent was used up in painting the iconostases of various churches (Stari Becej, Orlovat, Grgeteg, Ruma, Church of· the Transfiguration in Pancevo, and others), and in the portraits of eminent public figures (“Poet Laza Kostic,” “Petar Dobrovic”) and wealthy clients (“Woman with Glasses,” “Woman with Veil”). His historical composition, “The Refugees from Hercegovina,” is very dramatically rendered, and belongs to his early period, together with some moralizing paintings (e.g., “Cheerful Brothers…” a reference to the village drunkards), or sentimental themes (“Orphan on the Mother’s Tomb,” “Knitting Lesson,” “Under the Mulberry Tree,” and others). In some landscapes (“Roofs of Belgrade”), Predic lightened his palette, following the example of the “plein-air” stylists.

The other representative of the Academic Realism, Paja Jovanovic, also studied in Vienna, and lived in Paris and London. Throughout his long career, he was primarily occupied with portrait paintings; thus “Mihajlo Pupin,” “Draga Masin,” “Artist’s Wife” are some of the very many. Jovanovic also painted immense canvases inspired by historical themes, such as “The Coronation of Tzar Dusan,” “The Serbian Migration,” and “The Insurrection in Takovo.” His popularity in the world was based on the folklore-inspired compositions, and ethnographic inaccuracies depicting social customs and practices in Hercegovina, Crna Gora and even Albania. Among the most popular compositions are “The Preparation of the Bride,” “The Cock-Fight,” “The Traitors” and “The Fencing Lesson.”

A transitional phase between the Realism and the Impressionism is occupied by the so-called “plein-air” artists who worked outside their studios, studying nature directly, but still holding to established academic forms. In Serbian art they appeared about 1895, and continued until shortly before World War I. Their travels in pursuit of education saw them in the world’s art capitals: Munich, Italy, St. Petersburg (now Leningrad), Paris and London. Among the themes, the landscapes predominate. Marko Murat (1864-1944) was the painter of the Dubrovnik and its environment; Dragomir Glisic (1872-1957) was the painter of Serbian village landscapes. In addition, the still-life and other themes survive in their works. Generally speaking, their colors are rich, vivid, luminous, full of light and transparent shadows; the canvas texture is dynamic, and the light is more analytic than synthetic. This group consists of a number of artists, but further mention in this survey will be made of Djordje Mihajlovit, Rista Vukanovic and his wife, Beta Vukanovic, and artists which in their works approach the Impressionistic style quite closely: Borivoje Stevanovic, Ana Marinkovic, Branko Radulovic, and others.

Sculpture: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Generally speaking, Serbian sculpture fared quite differently than did painting and architecture. This was so because the church in observing the ease with which painting and architecture symbolized divine truths, early identified itself with them to form a lasting and harmonious association. Also, political and military considerations conspired to drain vital energies away from artistic innovation, and, as a result, sculpture was doubly subordinated. When found, however, sculpture was relegated to the exterior surfaces of churches (Raska style), present in form of decorative reliefs (Morava style), or applied to interior iconostases, icon frames, and doors (Byzantine style).

Consequently, after their migration to, and settlement in, the northern lands was completed, eminent Serbs followed the example of their forebears, and completely ignored the possibilities of the sculpture in the round. Sadly, this traditional neglect extended to the private lives of secular society, where only the painted portraiture seemed to be in demand.

Thus, a tradition of sculpture in the round was missing simply because it has never been allotted a place, first of all, in religious art.

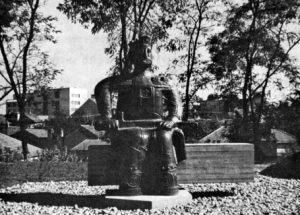

Owing to such circumstances, Serbian sculpture in the true sense of that word had a very late start. Petar Ubavkic (1852-1910) is regarded as the first Serbian sculptor of prominence. A stipend allowed this young Serb to study in Munich like so many of his contemporaries, who were painters. He spent two years there at the School of Applied Arts and the Art Academy (1875-1877), after which he returned briefly to his native Belgrade to teach modeling in a gymnasium. In 1878 Ubavkic sought inspiration in Rome, where he spent the next eleven years, studying at the Academy at first, and later on, working on his sculptures. Upon his return to Belgrade, he continued teaching and his artistic career. About twenty of his works remain; the most important period falls between 1877-1908.

Ubavkic’s extensive talent and training, skill and care in execution, sensitivity to the nature of his material – be it marble or terracotta – when combined with the Romantic sentiment and Realistic style, invited the attention of his contemporaries, compelled international recognition of, and awards for, his creations. Art historians consider him a rather able master of his craft.

The busts of “Vuk Karadzic” and the portrait of “Prince Mihajlo Obrenovic” attest to Ubavkic’s understanding of marble as a vehicle of expression. But his technical masterpiece must have been the “Woman with the Veil,” when the marble itself became a transparent veil revealing the features of the young face beneath. “The Monk,” “Karadjordje,” “Aleskandar Obrenovic,” the “Serbia” and the “Takovo Insurrection” groups, a “Gypsy” in terracotta and and an “Odalisque” (occasionally called “La Favoritta”), and the portraits of “Djura Jaksic,” “Djura Danieie,” and others, complete his artistic opus.

Although in spirit an artist of the 19th century, Ubavkic bequeathed a legacy to the next generation of Serbian sculptors, a generation that recognized his deep and personal understanding of materials, their complex individuality and nature, the very essence of the matter from which sculpture is created.

By sentiment and technique, Djordje Jovanovic (1861- 1953) belonged to the 19th century. He early studied architecture in Belgrade, but took up sculpture in Vienna, Munich, and, finally, Paris. Though possessed of considerable technical skill, infused with the Romantic spirit, the quality of his art is quite uneven. His large works, in spite of their size, seem to lack in monumentality (allegorical figures for various official buildings). He produced many public monuments, commemorating historical events (Monument to the “Heroes of Kosovo” in Krusevac) or nationally famous figures (“Prince Milos,” “Zmaj Jovan Jovanovic,” “Branko Radicevic,” “Vojvoda Misic” and others). On the other hand, his smaller works have been better received by scholars. They are more intimate, soft in outline and delicate. Academically inspired modeling is better manifested when infused with deep sentimentality (“Sorrow,” “Crnogorac on Guard Duty;” among the reliefs – “Smell of Roses,” “Serbia,” “War Victim,” “Serbian Soldier” and many others). After returning from studies abroad in 1903 he taught drawing, and later became professor and director of the Art School in Belgrade. He actively participated in the artistic exhibition in the country and abroad, especially during his first three decades of life in Belgrade.

The third representative of Serbian Realistic movement in sculpture was Simeon Roksandic (1874-1943). The son of a village blacksmith, Roksandic was sent to study in Zagreb, where he developed an interest in sculpture. Coming to the attention of some eminent Serbs, Roksandic was awarded a stipend to study in Budapest, where he completed his work with distinction in 1895. The following years were spent at the Academy in Munich, which regarded him as a most outstanding student. It was during his third year in Munich that he created one of his masterpieces, the figure of the “Slave” (lost since World War I). At the end of 1898, under the influence of fellow sculptor, Djordje Jovanovic, Roksandic came to live and work in Serbia, accepting teaching positions in gymnasiums (Uzice, Kragujevac). The sculpture of “Knez Milos” (in Kragujevac) dates from this time. He spent 1906 in Rome, where he created his famous statue of the “Fisherman” (two bronze casts: Belgrade and Zagreb). From 1907 he worked in Belgrade, and after the wars of 1912-1918 in which he participated, he took up teaching (from 1921) in the Belgrade Art School.

Although his style was influenced by German sculptural Realism, he was equally and profoundly inspired by the great Classical works of the past, above all those ,of the Hellenistic period. While his female figures do not directly emanate a power of expression (“The Dancer”), his sculptures of the boys (“Boy with the Flute,” “Boy with a Thorn in his Foot,” and others), together with his images of animals and figures testify as to his Classical inspiration (Two Lions,” “Boy and a Tortoise,” “Hero Killing Lion”). Among the bronze and marble portraits, his “Self-Portrait” and “Portrait of the Sister-in-Law” are outstanding.

His distinctive characteristics in the sculptural triad of the Serbian Realist sculptors lies in a powerful feeling for the expressive movement and a great sense for the composition, to which he adds his personal emotional values.

Subsequent generations of Serbian sculptors made progress by turning from Academism to Modernism, at a pace considerably slower than that of painters.

The art of Toma Rosandic (1878-1959) was profoundly tied to Belgrade, and to its art school and sculptural circles. Rosandic also studied in Italy; and with Ivan Mestrovic in Vienna, but was never admitted to the Academy there. After spending World War I with the Serbian Army, he made Belgrade his permanent home, continuing his sculpting and pedagogical activities.

His early years reflect both nationalistic feeling (“The Cycle of Kosovo”) and the tragedies of war through religious (“Ascetic,” “Head of Christ,” and one of his masterpieces, “Ecce Homo”) and deeply human themes (“Orphans,” “Widow”). He worked on small groups in wood, full of a very personal and intimate poetry (“Flute Player,” “Puberty”), or on the portraits (“Self-Portrait,” “R. Boskovic”), figures and groups (“Deposition,” “Harp Player”), as well as on the monumental sculptures (“Njegos,” “Horses”). Early Rosandic sculptures .are very much permeated by Mestrovic and German Expressionism, though he later outgrew them in preference to a stylized and modified Realism, deeply rooted in Mediterranean sculptural traditions. His technical abilities and his complete understanding of the materials are beyond dispute, as indeed are also clarity of expression and monumentality in style.

Sreten Stojanovic (1898-1960) started his career as a member of the organization of “Young Bosnia.” After the Sarajevo assassination (1914), he and other young Serbs from Bosnia were sentenced to prison, where he developed skills in wood carving, which would guide him toward his long and productive artistic career. After World War I, Stojanovic traveled to Vienna for his studies; but, finding the Vienna Art Center outdated and personally unsuitable, he left it for Paris. The dominant figures of the Paris sculptural world at that time were A. Maillol, Ch. Despiau, and A. Bourdelle, and it is with the last artist that he chose to study. Stojanovic did not fall under the exclusive influence of his master, but absorbed, especially in the treatment of the nude, influences from other leading figures. In the years between the two wars, Stojanovic traveled a great deal to various lands and artistic centers expanding his artistic vision. At the same time, in Belgrade, he produced sculpture, and was engaged in teaching, and in literary activities as a critic and essayist.

In the beginning of his career, stand his bas-reliefs in wood, in which scholars have detected the strongest impact of his French master (“Girl with a Flower,” “La Lutte,” “Rest” and others). Proceeding from wood to bronze, he remained essentially in that medium, developing a sense for the monumental (liThe Necklace”), which later served him well when executing public monuments following World War II (“Fallen Warriors” on the Fruskogorski Venac). He also fashioned small, more intimate bronzes, in which he successfully conveyed feeling for movement (“Dancer,” “Bathing Girl ,” “Girl with the Bananas”). But, the main force of Stojanovic’s talent was demonstrated in innumerable portraits which revealed understanding of psychology, whether in granite, marble, or bronze. In the hard materials the surface planes are simplified, almost geometrical (liMy Father,” “Portrait of a Friend”), and as timeless as the ancient Egyptian portraits. The others, for example, those created in bronze, frequently bear the imprint of a fast, almost Impressionistic technique (“Nikola Vulic”). Regardless of material or technical rendering, Stojanovic’s portraits have a lasting appeal (“My Daughter,” “My Mother,” “Milan Rakic,” “Pera Dobrovic”). His works were exhibited frequently in Yugoslavia and abroad during his lifetime and many are part of permanent national treasuries of museums, galleries and collections throughout Yugoslavia.

In this brief list one must include Petar Palavicini (1887- 1958) who was artistically formed in Prague, and who, although a native of Dubrovnik, made Belgrade his home. At first, thematically under the aegis of the national Romanticism (“Refugees from Kosovo,” “Jugovic’s Mother”), Palavicini’s style underwent an experimental phase in portraiture reminiscent of Cubism (“Rastko Petrovic”). Although he worked on decorative sculptural reliefs (allegories such as “The Crafts”) and friezes, as well as on the public monuments (“Student-Warriors,” “Karadjordje”), his main interest was the female figure: tall, elongated, elegant, and sensitively modeled forms (“Girl with a Bird”) to which the artist returned time and again. Above all, his permanent contribution to the Serbian sculpture rests on those female figures.

A somewhat younger contemporary of Palavicini, Risto Stijovic (b. l89l) came from his native Montenegro to study in Belgrade (with Djordje, Jovanovic). These studies were interrupted by World War I in which he served. Following that, he headed for France to recuperate from an illness and to continue his, sculptural training, first in Marseilles, and later, in Paris (1917). On the basis of exhibitions held in 1919 and after, critics praised the “Gothic” tendencies of the elongated and smiling figures, which he rendered with expressive directness and simplicity. Although he created public monuments (“Jovan Sterija Popovic,” “Botidar Vukovic”), portraits, female figures (“Caryatid,” “Indian Dancer,” “The Bathing Girl”), he appears artistically strongest when rendering the images from the animal world (“Eagle,” “Owl”). These animal sculptures are simple, essential, monumental, and, above all, universal and timeless.

The basic traditionalism of Serbian sculpture after World War II was enriched by the individual expressions of some artists (Jovan Soldatovic, Nebojsa Mitric), but it was left to yet another generation to break away from figurative conceptions. That gap was narrowed by such artists as Olga Jevrit (b. 1922). Having paid her debt to Classical sculpture by working with extremely simplified early figures and heads, Jevric turned to abstract Expressionism, expressing herself in large, often bulbous, forms in bronze, and by combining constructivistic elements composed of uprights and diagonals (“Complementary Forms”). Olga Jancic (b. 1929), a student of Toma Rosandic, continues the Classical tradition, as far as materials are concerned, which she limited to bronze and stone. Her expression is, however, both abstract and monumental, although somewhat reminiscent of prehistoric Lepenski Vir (“Medallion”). Yet another generation of young sculptors continues its visual exploration of materials and techniques, moving at will from the figurative to the abstract, and back again (Jovan Kratohvil, Momcilo Krkovic, Oto Logo, and others).

Architecture: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

The liberation of architecture from the domination of pseudoClassical and pseudo-National forms was even slower than in sculpture. Monumental works were predominantly left to Hungarian and German architects in the territories inhabited by the Serbs, but administered by Austria-Hungary in the 19th century. Among the Serbian architects of that period, Vladimir Nikolic (1857-1922) can be mentioned; his public buildings still survive in Novi Sad, Belgrade, and Sremski Karlovci (The Palace of the Archbishop).

(Photo: L.D. Popovich, 1971).

In Serbia proper, Andrija of Palanka and Djura of Potarevac raised fortifications (Topola) during the First Insurrection, and later some hostels within old monasteries. They and others like them received no formal training, but acquired their architectural skills in the traditional ways.

After the Second Insurrection, there is to be noted heightened architectural activity, although construction of any significance was traditionally limited to churches, public buildings, and princely homes (konak).

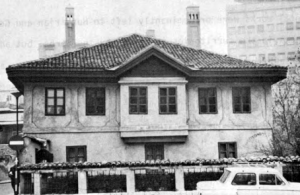

More than four centuries separate the era of Rad Borovic, architect of Ljubostinja, from that of Milutin Godjevac (Monastery of Bogovadja, 1816), or Janja Mihajlovic and Nikola Djordjevic (Rakovac Monastery; “Konak” of Princess Ljubica in Belgrade; Prince’s “Konak” in Toptider from 1831; and others). In spite of some Western elements, these examples support the existence of a regional, Balkan variant, of a more distant, Turkish, prototype.

Departure from such a tradition occurred toward the middle of the 19th century. It can be exemplified by the building donated by prosperous merchant Misa Anastasijevic. It is the former “Visa Skola,” and now the oldest part of the University of Belgrade. This structure was done according to the plans of Czech architect Jan Nevola, and it was completed in 1863. It shows a truly Romantic combination of Mediaeval (Romanesque and Gothic) and Renaissance styles in its polychrome arcaded facade.

L.D. Popovich, 1971).

Neo-Classicism was also affirmed in the building of the National Theater, which, though twice destroyed and rebuilt, still retains some of its original proportions. Its architect was Aleksandar Bugarski (1835-1891), who also gave Belgrade its “Old Palace,” now the City Hall.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a variety of “neo” styles proliferated throughout Belgrade. At the end of the 19th century, Svetozar Ivankovic (1844-1924), in designing the Ministry of Justice building, paid homage to the early Renaissance. The house of the prosperous merchant, Aleksa Krsmanovic, built by architect Jovan Ilkic (1857-1917) was of the Baroque ostentatiousness. The same architect made plans for the building destined to house a Russian insurance company, that later became the Hotel “Moscow” in Belgrade. Because the original plans for the facade were changed in Russia, an example of Art Nouveau now rises on the architectural face of Belgrade. Today’s National Museum was finished before 1914, according to the design of Andra Stevanovic (1852-1929) and Nikola Nestorovic (1868-1957). It is a very impressive, but pretentious neo-Renaissance structure.

World War I left Serbia in ruins, and the small number of its new intelligentsia, artists and architects included, was sadly thinned. A great deal was built by Russian architects, and, in general, this period marks an era of struggle between form and function. Contemporary architecture in Serbia begins with the works of functionalist architects such as Milan Zlokovic (1898-1965), who designed the Hotel “Zica” in the Mataruska Banja, and the Children’s Hospital in Belgrade. He was followed by Dragisa Brasovan (1887-1965), an exceedingly well-trained architect, with a sure sense of style (State Press Building, Belgrade; Air-Force Command Building, Zemun).

World War II did not spare Belgrade in the least; the greatest part of the city lay in ruins requiring extensive reconstruction. Principles of modern functional architecture, as understood in the United States or Japan, were fully adopted by the new generation of the Serbian architects, already completely schooled in the country (University of Belgrade). Among the more prominent names are: Vladeta Maksimovic, Milorad Pantovic, Ratomir Bogojevic. But the consequences of the war, as well as the oscillation between two divergent ideologies; caused a crisis in Serbian architecture in the late 40’s and early 50’s (The House of the Syndicates). Many names were, and are, involved in the creation of the New Belgrade – a city within the city, on the flatlands between the rivers Sava and Danube, and across from Belgrade itself. Although impressive as a unit from a distance, one finds fault with the great concentration of population in the buildings designated as family dwellings in relationship to the green areas left for them. Among others, the following architects worked there: M. Jankovic, B. PetriciC, U. Martinovic, M. Mitic, D. Milenkovic, and others.

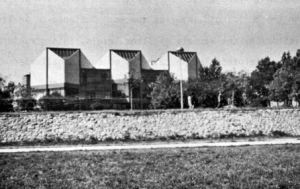

Within the complex of New Belgrade, one building stands alone in the excitement it generates. An example of a new direction taken by architects Iva Antic and Ivanka Rospopovic it stands on the banks of the Sava, overlooking Kalemegdan. It was created to house the collection of contemporary arts. Simple cubic masses are relieved by many-faceted roof surfaces, which shed rain and admit light into the building’s interior spaces. Designed to invite and entice visitors by the variety of floor levels, this structure is certainly a masterpiece in the category of muse.um galleries which, everywhere until recently, were burdened by tradition.

Painting: The Twentieth Century

While the products of the early decades of this century can be securely judged by the art historian, more recent paintings still belong to the domain of the art critic, and to time for what one hopes will be their enduring values.

Historical events made clear divisions in the evolution of the Serbian painting of this century: the new era which began with the exhibitions of the “Lada”, art association in 1904, ended with World War I. It was at the point that Serbia, together with Croatia and Slovenia were united to form a new political unit – the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The second period covered the years between the two World Wars, and the third began at the end of World War II, when the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia was created.

Since the exciting developments in 20th century Serbian art are too complex to treat in the space of a single survey, only the representatives of major movements will be mentioned . Indeed, by identifying movements and artists, this writer wishes to invite the reader to become an active participant and to discover for himself. The works are there, made to be seen and judged by the observer.

Fin de siecle art reached Serbia and was expressed chiefly through Uros Predic and Paja Jovanovic, who worked well into the 20th century. While Academism continued to live, opportunities were sought in different artistic expressions. Those are somewhat chronologically retarded in relationship to the European development, but none the less, some very brilliant accomplishments were made.

These movements were welcome not only in the sense that they brought timely end to that exhausted style, but they were educating the taste of the youthful and unsophisticated Serbian bourgeois society. The transition was marked by the plein-air painters and those who belonged to the art nouveau trend, but above all, by impressionists. Impressionism, born in France and requiring new artistic sensibilities, did not reach Serbian artists directly from Paris, but via Munich, where the majority of Serbian artists still went for schooling. The first traces of the usage of pure color on v canvas can be found in the landscape “Ziea” by Djordje Krstic (1851-1907), and less so in the works of Stevan Aleksic (1867-1923), Rista Vukanovic (1873-1918), and others. The evidence of a struggle to escape worn-out techniques and themes of Academism is apparent. Thus, the transition toward Impressionistic style is predominantly formal: dark coloring still predominates while only some of the colors shine brightly.

Ljubomir Ivanovic (1882-1945) is considered to be one of the first Serbian Impressionists, although he found his way of expression through graphic means. His formal education occurred in Belgrade and Munich, while his works were exhibited from 1904 from Yugoslavia to France. While his particular talent was less receptive to color – that main vehicle of expression of the Impressionist – he deserved to be classified with them owing to the Impressionistic feelings conveyed through his pencil drawings and wood-cuts, which, skillfully drawn, were able to suggest the play of light in his monochromatic technique, conjuring the vision of the shimmering surfaces of the Impressionistic paintings. His drawings and woodcuts are also fascinating records of the places and landscapes, now changed beyond recognition in many instances (“South Serbia,” “Sumadija,” “Yugoslavian Landscapes,” “Old Paris” and other themes), which, together with the maps and illustrations for books, comprise his opus.

Among painters of his generation, Kosta Militevic (1877-1920) (“Vozdovac Church” and “Savinac Church,” c. 1913) is noted for pure and rather cool colors, applied thickly by brush. This artist of irregular schooling (Belgrade – Prague – Vienna – Munich) slowly reached artistic maturity, produced several masterpieces during the exile with the Serbian Army on the island of Corfu and in the city of Thessalonike in the course of 1917-1918. The image is suggested through the mass and surface or space, rendered in thick strokes of the brush, set off against vibrant harmonies of blue and yellow, green and red, ochers, cobalts, and ultramarines (“River on Korfu,” “Guard in an Olive Grove”).

Milan Milovanovic (1876-1946), the second most important Serbian Impressionist, had a short career as a painter, but enjoyed a longer one as a teacher. After completing his studies in Paris (1903) toward the end of the first decade of the 20th century he traveled through South Serbia, Macedonia, and Mount Athos, painting and cleaning mediaeval frescoes. During the Balkan and First World Wars, he painted on the military front, and afterward in Italy and Southern France. Following the setting up of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Milovanovic exhibited his work with other Yugoslavians in Paris and Geneva. Upon his return to the country, he dedicated most of his time to teaching at the Belgrade Art School.

His early works (c. 1902-1903) pay tribute to Manet, as interpreted by the Munich School of Impressionists; hence, the tonality is gray. During a stay in Paris, that manner was abandoned in sketches and above all on small canvases, such as “Carrousel.” On his portraits from that early period surface texture is strongly emphasized, while the brownish tones are still very much in evidence (“Self-Portrait with the Red Tie,” “Portrait of the Artist’s Mother”).

The effect of his having visited the South is very strikingly seen in his painting; after that colors shimmer on the surface, bright and brilliant (“View of Belgrade,” “Gracanica,” “Hilandari,” “Skopje,” “Dusan’s Bridge,” etc.). The most pure in colors are the works from Capri (“Terrace,” “Landscape,” “Blue Door”). His last cycle consists entirely of landscapes and scenes from the southern part of the Adriatic (“Dubrbvnik,” “Red Terrace,” “Lapad,” “Gruz” and others).

Creativity ended when his pedagogical work was begun. The scholars have classified his creative years into fiVe periods, and it is believed that he created about two hundred and fifty canvases of which a relatively small number have survived. Although predominantly an Impressionist, who paints pink and blue or green luminosities, his light never dissolving the structure of his painting, he also oscillated between the Fauvism and the neo-Impressionism, thus not only developing in breadth of vision, but moving forward as well.

The most eulogized artist and powerful personality of her generation was a woman – Nadezda Petrovic (1873-1915). Coming from an artistically talented family, she devoted some of her time to the artistic organizations, to exhibits in the country and abroad, to art critiques, and social involvement (in the line of duty as a nurse during World War I she died of typhoid fever). Her studies took her to Belgrade, and then to Munich, where she became tightly connected with the Slovenian art circle (R. Jakopic, I. Grohar, M. Jama in the studio of A. Azbe). Her early works, already powerful in color and frequently executed in tempera, record her travels in Germany, France, and Italy. In a brief fifteen year period she passed from plein-air to Impressionism, and into Expressionism (Fauvism), modifying each, and so joining Serbian art with the most contemporary movement in Europe. Although many of her works were destroyed, about 200 survived. These works characterize her vision of France (“Notre Dame,” “Bois de Boulogne”), and, above all, Serbia, its people, and landscapes (“Self-Portrait,” “Gypsy Woman,” “Woman in an Interior,” “Resnik” and many others).

Among her contemporaries, she alone emerges as an artist of monumental quality, standing firmly on her beliefs against a conservative environment. In paying tribute to an older art in monochromatic works and those negating color, she developed her most powerful means of expression (“Prizren”). This phase was characterized by the achievement of personal freedom of expression, reached not through subtle aesthetic analysis, but through broad, free strokes, almost relief-like in the foreground plan of many paintings. The effects are striking: directness in rendering the depth of vision, of passion, movement, and drama. Her honest observations radiate with power and life and truth, enshrined in the blues and purples, reds, greens and golds – so forcefully expressed that she stands above her contemporaries.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Serbian art oscillates between Munich and Paris, between old Academism and new Fauvism. As always, indications were that the new ways were winning over the conventional ones.

The second phase of the modern art in Serbia took place within Yugoslavia, and it, too, barely lasted a generation. Marked by the search for the avant-garde, the effort was full of conflicts and contradictions. The Parisian influence was pre-eminent among artists of the early 20th century who regarded color as the mode of expression, among those who for a decade between 1920-1930 went in search of abstract form under the influence of Matisse, and Cubism.

During the decade immediately preceding World War It, Serbian artists had some difficult moments adjusting to the pace with which, in the art world, movement succeeded movement. It is also characteristic of that period for trends to overlap, and for artists to pass through more than one phase or style.

The Sezannesque vision of the world was shared by the following three artists: Petar Dobrovic, Jovan Bijelic, and Milo Milunovic – but not exclusively. Sava Sumanovic, Zora Petrovic, and Petar Konjovic were influenced more by the rationalistic trend in art of A. Lhote.

Though impressed by that which was Parisian and novel, some Serbian painters of this generation nevertheless took a retrospective glance at Cubism and found it attractive; and especially so in the dominance it exercised over color (emotional expression) through volume and space (rational expression). Cubism, though felt, was never fully and exhaustively explored during this phase of Serbian art (S. Sumanovic).

Toward the concluding years of the fourth decade of the 20th century, Serbian painters continued their exploration in several directions, although the approach in the majority of cases called for emotional involvement of the artist on personal and social levels. Scholars refer to that and similar tendencies as Coloristic Expressionism, Surrealism, and, finally, Intimism.

It is possibly an exaggeration to conclude that Serbian painters found in color the means by which they achieved the fulfillment of artistic vision. Nevertheless, it seems to be so. Serbian Expressionists literally rejoiced in the experience – freedom to explore all the elements of nature and life through pure color contained within a firm and formal equilibrium. One can almost sense their affinity with the old fresco masters of the Middle Ages. No differences were too irreconcilable, no distances too great to bridge. The vision is often localized, focused, and slowly removed from the nature of the subject, which then entered the domain of the symbol. Compositional order and drawing were subordinated to the exalted brilliancy of colors. This trend is best manifested in the works of J. Bijelic, P. Dobrovic, I. Job, M. Konjovic, and Zora Petrovic.

Frequently in history, artists have reacted to the external world very much like sensitive instruments. Social, political, and economic conditions affecting the world of the late 1920’s were held up and methodically examined by artists as well as social and political scientists. In Serbian arts, Surrealism, which first manifested itself among writers, does appear among the painters (Radojica Zivanovic – Noe, Milena Pavlovic – Barilli), while other painters expressed their comments on the state of the world through the visual language of Social Realism (the group “Life” with Djordje Andrejevit – Kun and others).

The phenomenon of the Intimist originates as a withdrawal from an outward manifestation of commitment to ideas (Marxism and Marxist painters) or Baroque restlessness of Expressionism. Inspired by Paris masters (P. Bonnard, E. Vuillard) the Intimists are easy to like visually, since they returned to the more gentle realities of their surroundings, made poetic through refined means, inner light, and tranquility. Gentle sensitivities underlie renderings of nudes, landscapes, and interiors. The warmth of general tonality is stressed, and the feeling of space is considered more important than stormy and emotional surfaces.

Each of the artists of this group contributed a personal and individual expression to the style. Marko Celebonovic, Predrag-Pedja Milosavljevic, Stojan Aralica, Ivan Radovic, Nedeljko Gvozdenovic, Ivan Tabakovic are among its most talented exponents.

The advent of any war inevitably makes cleavages in the continuum of a civilization. Human energies are then diverted from various aspects of creativity and turned toward finding monstrous ways of destruction or ingenious ways of survival. World War II did not prove to be an exception to this rule in regard to the whole world in general, and in regard to a very small part of that world – Serbia – in particular. There, the war brought terrible destruction and devastation which far outweigh attempts at creativity (Dusan Vlajic, Djordje Andrejevit – Kun and a few others).

The period after 1945 continued with the old, inherited complexities in addition to the new tendencies. These were imposed on the one hand by the new system and philosophy (Marxism – Communism), and on the other hand, the continuous call of the progressive art emanating from Paris. Still active are veteran painters who, from the second decade of the century, continued to oscillate between the outdated Academism and the much explored Impressionism. The artists formed on the basis of Paris avant-garde movements of the 1920’s and 1930’s were reaching another plane of maturity. In their works they searched for yet another, more refined sentiment. In the Intimist style, others rise from the bounds of Expressionism into the total artistic liberation of the Abstract Expressionism. Besides these, there are artists still painting coloristically sonorous canvases as the last and distant reflections of the Neo-Impressionism.

Parallel to the generation dedicated to the Social Realism and its ideology, there were artists of the early 1950’s which, once again, brought Serbian painting abreast of happenings in the great art centers. Their thrust was upon the subject which was made free from itself, and raised to the elevated height of a symbol – not unlike that of the religious painting of the Middle Ages. Their expressions are individual, and they are able to carry their art to the boundaries of the abstract and of the non-figurative, thus reaching into the aesthetics and the theory of the artists of the 1960’s.

The search was feverish, the changes fast – barely half a generation separates the work of Social Realism, all dedicated to express a strict utilitarianism both social and aesthetic (Djordje Andrejevic-Kun; Boza Ilic) – from the works so diametrically opposed to it, and responsible only to the abstract and personal vision. The generations of Serbian artists working from the 1950’s are as numerous as they are diversified. They are our contemporaries, and they are better when experienced directly, rather than when explained, classified or described. As the artists emerge with their works, these works are discussed by critics, and they are yet awaiting to be judged by time. Strong are the artistic forces of powerful Expressionism (Bata Mihajlovic, Petar Omcikus, Lazar Vozarevic, Olivera Galovic, Petar Lubarda, together with some already mentioned painters such as Pedrag Milosavljevit).

Artistic groups are formed and reformed. New centers and epicenters are felt, departures taken, and gaps filled by the younger talents (Mladen Srbinovic, Stojan Celie, Miodrag Protic, Aleksandar Tomasevic). They are not afraid to experiment with the world of vision, touched with Surrealism, or with pure forms and shapes, colors and tonalities, or atonalities as well (Milos Bajic, Zoran Petrovic, Mica Popovic, Ksenija Divjak).

Those elements which bind the youngest generation of Serbian painters together, such as variations on Realism, including the ever strong Surrealism (Milic Stankovic, Dado Djuric, Ljubo Popovic) and every manifestation of abstract art, including Optic and Cynetic, bring these artists closer to their fellow creators the world over.

The years subsequent to World War II brought inevitable changes to the universe. New technologies made the world smaller and nations closer, if not friendlier. The creative energies were revived worldwide. Artistic sensitivities once again registered the changes, with optimism or pessimism, with the enticement to beauty or with the conscious discords which jarred the senses. The artists formed a rather unique brotherhood, be they architects, sculptors or painters. Their sharing in the new universalistic . spirit made them transcend the nationalistic, regionalistic and political boundaries. They became elevated above the provincialism and sectarianism of diverse schools and continents. The younger generation of Serbian artists creating during the third quarter of the 20th century – whether in Belgrade, Paris, New York or Los Angeles – seems to share, as much as possible with the other artists of the world, in this universal spirit and style, which seems, at least Tor the time being, to have conquered all the boundaries created by nature or imposed by man. It is upon the future generations to decipher how much of their Serbian ethnic spirit and artistic heritage was transmitted to the universalistic trends of today.