Main Body

Chapter 11

All through the night of June 13th and into the next day Tinkerbelle raced along before the strongest wind we had yet encountered. It was exhilarating, and it was exhausting, for the sea grew heavier every hour. Waves slammed into our starboard side without warning, and it was all I could do to handle the sheet and the tiller and stay on course. But I was determined to hang on, tired, sore and scared though I was, in order to make up for lost time; and so we kept driving on through the day and into the cold night.

It was no time for exuberance; we were perched too precariously on the thin line between maximum speed and minimum safety. To remain on that perch demanded senses tuned to their greatest receptivity. It called for unwavering alertness; instant detection of the slightest change in conditions and swift, appropriate responses. A moment’s inattention could be disastrous.

I knew all this well, but it didn’t help. The wind pulled a diabolical trick. It increased in force so stealthily I failed to perceive it until whammo! a puff caught the mains’l at the same time a wave struck the stern and Tinkerbelle spun around a full eighty degrees, paying no attention whatever to my frantic yank on her tiller. She wound up stopped dead in her tracks, facing into the wind, her sails flogging ineffectually with snapping sounds like firecrackers going off that meant the fabric might soon be ripped to shreds.

Fortunately, she started drifting backward almost at once and the rudder drew her stern around so that she went over onto the port tack and the flogging stopped. The sails were saved. I kept the genoa jib sheeted to the weather side and fastened the tiller and mainsheet on the lee or starboard side to heave her to. A reduction of the sail area was overdue.

A few minutes later the big red mains’l was down and lashed at the boom and we were continuing on our way under the genny alone. Even so, we sped along almost as fast as before, for the wind in those few minutes had increased markedly. It also had veered toward the west.

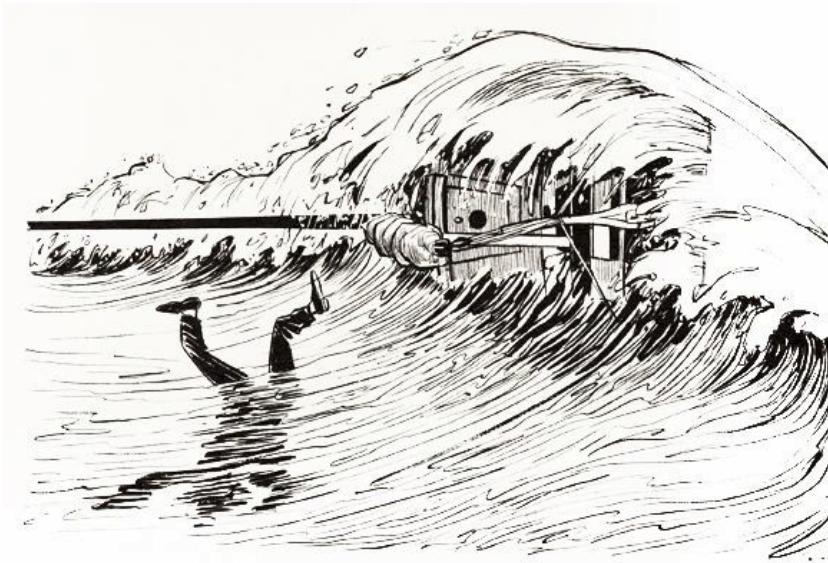

By the time the first lightening of the eastern horizon signaled the approach of daybreak and the longed–for blessing of the sun’s warmth, the wind had moved all the way around to the west and now blew from directly astern. For a while the sea was confused. Then the waves, by degrees, adjusted to the changed direction of the wind. They grew higher and steeper as they bore in from behind, rank on rank, flinging us forward in spasms of breakneck speed. Clutched in a welter of sizzling foam, we surfed giddily down the forward slope of a breaking wave, paused for a moment in the trough as the wave raced ahead and then, when the next one grabbed us; repeated the maneuver. And so it went, on and on. It was exciting. It was also dangerous.

The chief hazard was that we might broach; that is, slew around broadside to the waves. A breaker striking Tinkerbelle in that position could knock her down, even roll her over and over. It might dismast her or inflict other dire injuries. It was a catastrophe to be resolutely avoided.

So, favoring discretion over sailing valor, I decided the time had come to put out the sea anchor again. I hated to end our eastward gallop, but consoled myself with the knowledge that even while riding to the sea anchor we would continue moving eastward, drifting toward the west or even the north or south.

As soon as I got the bucket anchor out, the rudder off and the genny down, the strain on my nerves eased up and I could almost relax. Tinkerbelle seemed to appreciate the change, too. For a little while her motion was less violent; water sluiced across her deck less often. But the waves continued to grow. I could see them clearly in the brightening daylight. They were huge. They resembled rows of snow–capped mountains marching toward us. The mountains themselves weren’t especially terrifying, or even their snow–capped tops. What really made my hair stand on end was the sight of one of those snowy tops curving forward and falling, carumpf! into the valley. What if one of those avalanches rammed into Tinkerbelle broadside? Oh, brother!

I was tired. So far I’d gone more than twenty–three hours without sleep and goodness only knew how much longer I’d have to go. The skin of my face felt stretched taut. It burned from the protracted buffeting of wind and spray. I was shocked to discover my eyelids were beginning to droop and my head to nod. I even had some trouble focusing my eyes.

This is no good, I said to myself. I’ve got to snap out of it.

Quickly, I opened the cabin hatch, leaned inside, rummaged in my medical kit until I found a stay–awake pill, downed it with a swallow or two of fresh water and closed the hatch again. I moved fast, for I didn’t relish the prospect of maybe having Tinkerbelle flipped over while the hatch was open.

The pill took effect swiftly. In a minute or two I was bright–eyed and bushy–tailed, the need for sleep seemingly banished. That was better, much better.

I thought how wonderful it would be to crawl into the cabin and at least get out of reach of the wind, but I didn’t have the courage or the faith in Tinkerbelle to do it. I feared she might be capsized, trapping me inside her, and I imagined that that wouldn’t be much fun. So I remained outside in the pitching, bounding, rolling, yawing, dipping, swaying, reeling, swiveling, gyrating cockpit, exposed to the merciless clawing of what by then was either a full gale or the next thing to it.

Hanging on to avoid being tossed overboard by my little craft’s furious bucking, I offered up prayers to God, and Neptune, and Poseidon, and all the sprites who might be induced to lend a hand in my hour of need. And then, just to be sure I hadn’t overlooked a bet, I prayed “To whom it may concern.”

I hunched down behind the cabin to escape the worst of the wind and flying spindrift, but every ten minutes or so I popped up to take a quick look around the horizon to see if there were any ships about. It would have been a splendid time, while we were riding to the sea anchor, helpless, unable to maneuver, for a big freighter to come along and run us down. We made a dandy target with that hundred and fifty feet of line stretched out from the bow. A picture flitted into my mind of Tinkerbelle and me being chopped into little pieces by the slashing, cleaver-like propellers of an Atlantic juggernaut.

From the tops of the waves I could see four or five miles, maybe farther. A reddish glow in the east foretold the imminent appearance of the sun. How I yearned for its heat! It would make life worth living again. Banks of orange–looking clouds hugged the northwest quadrant of the horizon, making it seem as if there must be land there, although, of course, there wasn’t. The sky had already turned from black to gray to white and now was turning from white to pale blue. Except for the northwest sector, close to the sea, it was almost clear. Only a few small billowy clouds dotted its vastness.

With the arm I didn’t need for holding on, I beat my chest and rubbed my legs in a frantic effort to generate warmth. I wriggled my toes and, as well as I could under the circumstances, made my legs pedal an imaginary bicycle. The exercise and the friction helped. It produced a mild internal glow that dulled the icy sting of the wind. It also gave me something to do, which, for the moment at least, relieved the mounting apprehension aroused by the incessant crashing of breaking waves and raving of the wind.

In another twenty minutes or so, at about 4:30 A.M., the sun bobbed up and so did my spirits. The red–gold rays burnished the varnished mahogany of Tinkerbelle‘s cabin and sent waves of radiant relief deep into my chilled hide. The sight of my own shadow made life appear ever so much brighter and, somehow, this deep blue ocean of the day didn’t seem nearly as threatening as the inky black one of the night had seemed.

What happened soon afterward happened so fast and, believe it or not, so unexpectedly, that I still don’t have a clear picture of it in my mind. I remember I was reveling in the growing warmth of the sun and in the improved prospects for the day when a wall of hissing, foaming water fell on Tinkerbelle from abeam, inundating her, knocking her down flat and battering me into the ocean with a backward somersault. One moment I was sitting upright in the cockpit, relatively high and dry, and the next I was upside down in the water, headed in the direction of Davy Jones’s locker.

I flailed my arms and legs, fighting to gain the surface. I wasn’t exactly frightened; it had all taken place too fast for that. But the horrible thought of sharks passed through my mind and I was gripped by the awesome feeling of being suspended over an abyss as I recalled that not long before I had figured out from the chart that the sea was about three miles deep at that spot. No use trying to touch bottom and push myself up to the surface.

I struggled harder as pressure began to build up in my lungs and behind my eyeballs. I hoped I could get my head above water in time to avoid taking that first fatal underwater breath that would fill my lungs and, no doubt, finish me off.

My lungs were at the bursting point when, at last, my head broke out of the water and I gasped for air. I expected to find Tinkerbelle floating bottom up, her mast submerged and pointed straight at the ocean floor, but she had righted herself and was riding the waves again like a gull. We were no more than eight or ten feet apart.

I reached down, caught hold of the lifeline around my waist and hauled myself back to my loyal friend. Then, gripping the grab rail on her cabin top, I tried to pull myself on board.

I couldn’t do it; the weight of my wet clothes made the task too great for my limited strength. Nevertheless, I tried again. Still no go, so I rested a moment.

There must be an easier way, I thought as the boat and I rose and fell to the waves in unison. Of course, I could have taken off my clothes, put them on board and then climbed aboard after them, but I hoped there was a quicker way. And then it came to me: hold the grab rail with one hand while floating close to the surface, get a leg hooked over the rub rail and onto the deck, and then pull up. I was given extra impetus by the mental image of vicious, snaggle–toothed shark possibly lurking nearby and preparing to take pounds of flesh out of my quivering body, so, on the next try, I made it.

Puffing heavily, I flopped into the cockpit and lay there clutching the handhold above the compass as my breathing slowly returned to normal. The situation, to state the case mildly, could have been a lot worse. I had been given a bad scare and was soaked through, but nothing really calamitous had happened. Tinkerbelle was still right side up and clear of water, and neither she nor I had suffered so much as a scratch. And, best of all, I now had evidence of exactly how stable she was. That one piece of empirically gained knowledge transformed the whole harrowing experience into a blessing in disguise. There would be no more torturous nights in the cockpit; from now on I would sleep in comfort in the cabin, even in the foulest weather, with the assurance that my boat would remain upright. No longer did I need to fear being trapped there by a capsize. This discovery made the remainder of the voyage immensely more enjoyable than it would otherwise have been.

The steepness and dangerous size of the breaking waves remained undiminished, however, so I had to remain alert. There was no telling when we might be bowled over a second time. Although sopping wet, I was reasonably comfortable because my rubberized suit kept out the wind and the rising sun was beginning to produce the warmth I had longed for all night. It was a beautiful day, in fact, with white, cottony clouds flecking the inverted blue bowl of the sky, and white, foaming wave crests flecking the undulating, deeper indigo platter of the sea. If it hadn’t been for the force of the wind and the size of those waves, it would have been a perfect day for sailing.