Main Body

Chapter 5

We arose early the next morning, Sunday, May 23rd, and, after a hurried breakfast, started loading my supplies into our little station wagon. This job took much longer than expected, so we weren’t ready to leave until after 3 P.M.

The goodbyes were relatively painless, for no tears were shed. We kissed and hugged with assurance that we weren’t doing it for the last time. My mother and the two children understood what I aimed to do and were confident I would survive, although they may have had some doubts about whether I would get all the way across the ocean. It may seem odd, but the goodbye I was most concerned about at this time was my goodbye to Chrissy, our five–year–old German shepherd. After all, I was able to explain to my mother and the children why I was leaving and how long I’d be away, but to Chrissy it would almost certainly seem as though she had been deserted. I couldn’t possibly explain to her that I’d be back in three months. Nevertheless, I tried to be reassuring by speaking affectionately and rubbing noses with her and scratching her neck, the way she loved me to. And anyway, maybe she wouldn’t miss me much at that, for now, instead of having to sleep at the foot of my bed, she’d get the whole bed to herself. Come to think of it, after three months of such indulgence she might be sorry to see me return. No matter; she was my special girl and I loved her.

Then I bade a fond farewell to Fred, our cat, and to Puff, Douglas’s iguana, and climbed into the driver’s seat beside Virginia and her brother. The car’s springs sagged with the weight of the provisions and of Tinkerbelle hitched on behind, but all we could do was hope the strain wouldn’t be too much for them. We had to get moving. So, with waves to mother, the children and the gathering neighbors, we struggled off, the engine laboring mightily.

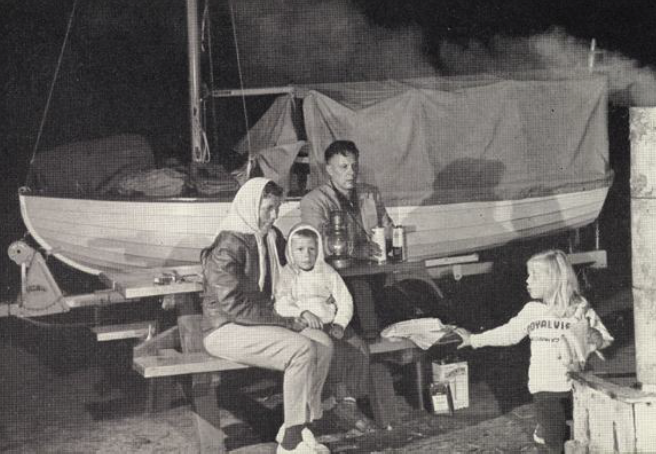

We were blessed with good fortune, for the next day at about 7:30 P.M. we arrived in Falmouth, after an overnight stay at a motel near Batavia, New York, without the car’s having suffered any sort of breakdown. We put up at a very comfortable motel about a quarter-mile from Vineyard Sound, and before we went to bed that night, we drove down to the shore and looked out over the water which, in a few more days, Tinkerbelle and I would traverse. I’m not sure what the others felt, but I tingled with an intense sensation of awe.

The next day we devoted to sightseeing, as if we were a group of tourists. We had breakfast at a charming little place in Woods Hole and, afterward, looked over the buildings of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution where my brother had once been employed. Then we drove to Chatham, at the southeast corner of the Cape, and browsed through some souvenir shops, in one of which I bought Virginia a little silver dolphin for her charm bracelet. “A lucky dolphin,” I called it.

What made Chatham especially interesting to me was the fact that in 1877, Thomas Crapo and his wife had sailed from there in the 19 ½–foot New Bedford, bound for England. They arrived at Newlyn, near Penzance, Cornwall, fifty–one days later, after a truly remarkable voyage.

We went on, next, to a lovely sandy beach where we ate a fine picnic lunch as we looked out over the blue Atlantic, which, that day, was in a warm, contented mood. And then we visited Provincetown and saw some of the fascinating characters of that famous art colony. We also fed a huge flock of sea gulls from the end of a long pier where the fishing boats docked.

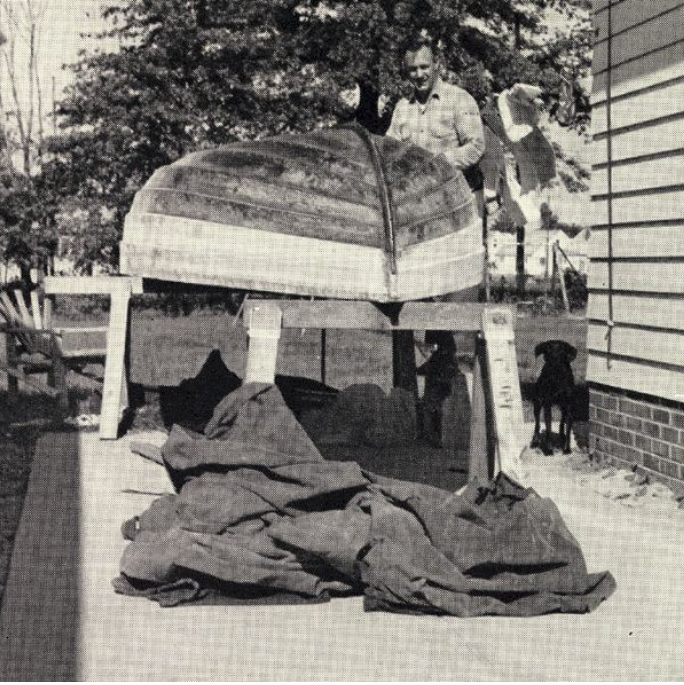

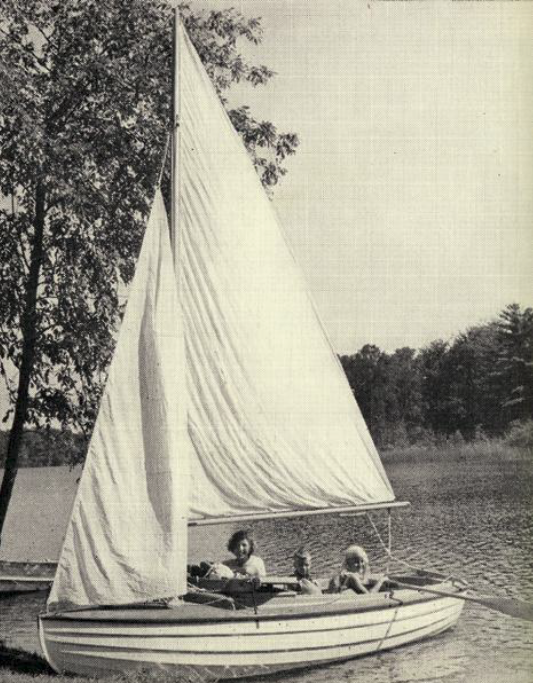

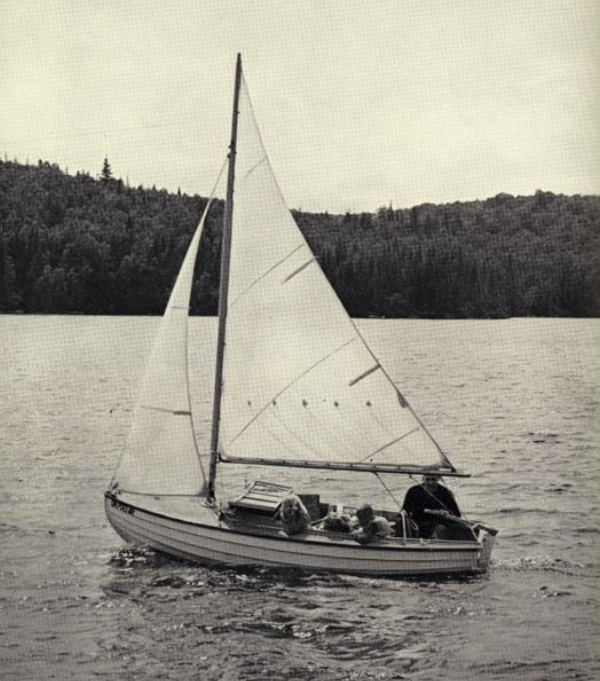

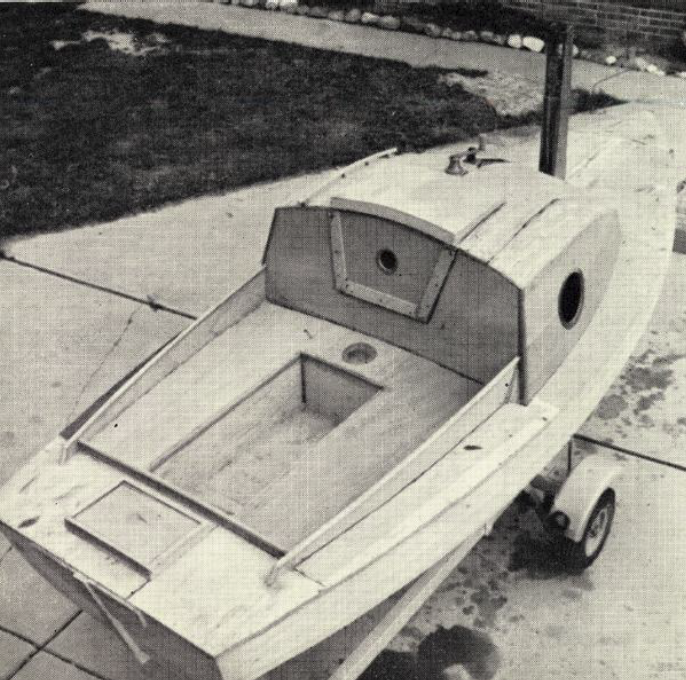

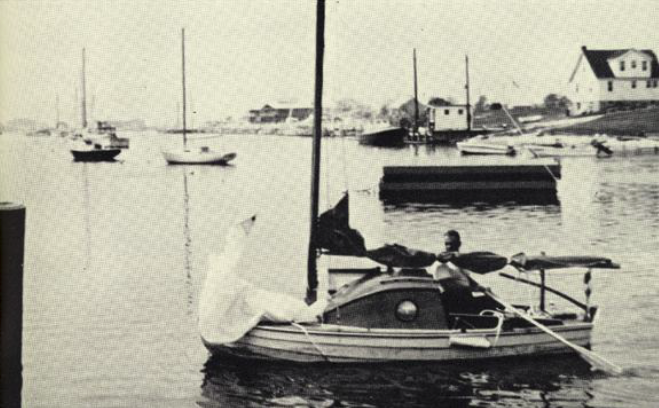

The following day, Wednesday, May 26th, we trailed Tinkerbelle over to Falmouth’s Inner Harbor and, at a marina operated by F. W. (Bill) Litzkow, a big, friendly man, Tinkerbelle was hoisted from her trailer and lowered into the salt water. It was her first taste of the sea and she took to it as though she’d been tasting it all her life.

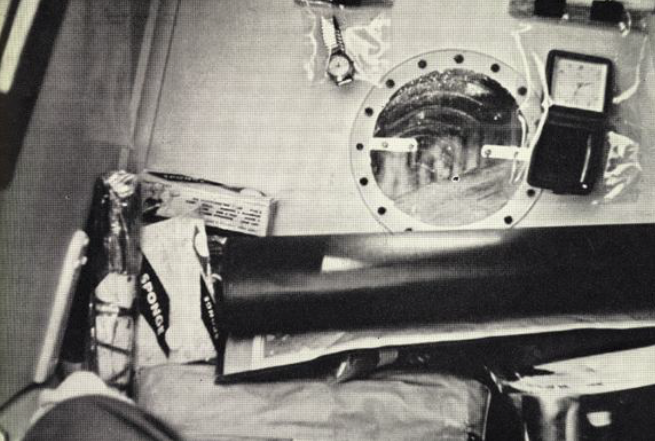

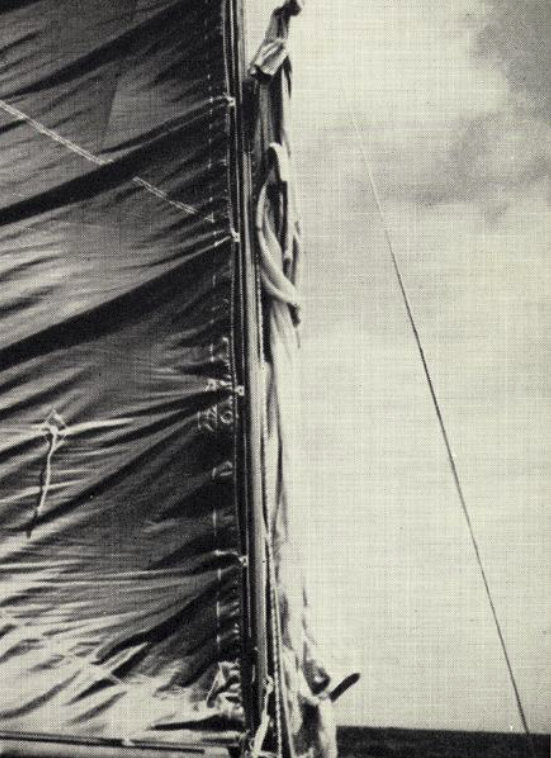

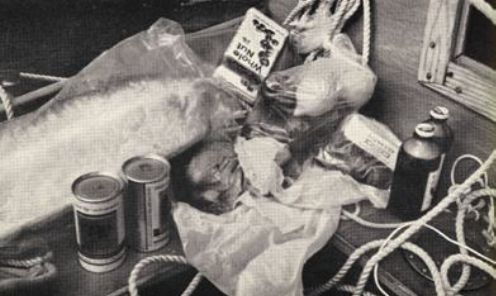

But I couldn’t stand around just admiring her; there was a lot to be done. We had to load her. I paddled her over to a nearby dock and went to work raising her mast and bending on her sails while Virginia and John filled all the plastic containers with water and brought them over to be stowed away under her cockpit. Then I packed in the eight big bags of food and the Victory Girl, sextant, radio, blankets, charts, spare batteries, flotation planks and all the rest of my equipment. There were an awful lot of things to get into that little boat, but somehow I found a spot for everything. When the loading was completed, Tinkerbelle was sitting lower in the water than she’d ever done before. I guess she had only eight or nine inches of freeboard although, empty, she had more than twelve inches.

The lack of freeboard didn’t worry me. I believed the weight would give her increased stability. And I kept thinking of something Ben Carlin had written in Half Safe. He had said freeboard was like a chin stuck out to be hit. To me, that made a lot of sense.

While the loading was under way, Bill Litzkow’s eyes must have bulged at the sight of all the material we were putting aboard.

“Where’s he going?” he asked Virginia and John in a confidential tone. “England?”

My two fellow conspirators were taken aback, for no one else had suspected our secret.

“How’d you guess?” said John, with a mysterious grin.

Then he and Virginia swore Bill to silence, and Bill promised he wouldn’t breathe a word to anyone. He kept his word, too. He didn’t even mention it to me in the five days I remained at his dock preparing for departure. I found out later that after I’d gone he telephoned Virginia and finally got her permission to break his silence. Bill was a man you could trust.

Another man you could trust was Virginia’s brother, John Place, a rewrite expert on the Pittsburgh Press. He was using a week of his vacation to help Virginia and me, and, although he considered my voyage extremely newsworthy, he didn’t even tip off his own newspaper until I was safely out of reach at sea. That was rare trustworthiness.

Late that afternoon we did some more shopping. Virginia bought me a fine sweater and a book about sea birds to help me identify the birds I saw on the Atlantic (I already had two other books I hoped to read along the way: Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind and John Le Carre’s The Spy Who Came In from the Cold), and John got me a harmonica and some books of music to help pass the time if and when I was be calmed. And in the evening we had a delicious farewell dinner at a restaurant overlooking the harbor. I think we all felt a little self–conscious, not knowing quite what to say, but we enjoyed ourselves, anyway.

The next morning John and Virginia began their journey back to Willowick with Tinkerbelle’s trailer.

There is an old superstition of the sea that if you wave a ship out of sight you’ll never see it again. John and Virginia wouldn’t be there to wave me out of sight when I set sail, but I was there to wave them out of sight as they set off for Willowick; and I brought them a heap of misfortune. Not even the lucky dolphin I’d given Virginia could forestall it. On the New York Thruway, near Oneida, right at a tollgate, the car gave up the ghost and refused to budge. Virginia told me later over the telephone.

They’d had the car towed to a garage, where it was learned that the engine was beyond repair; they’d need a new one. So Virginia wired our bank for some money and they got the new engine and finally, after dark on May 29th, a day late, they arrived back in Willowick.

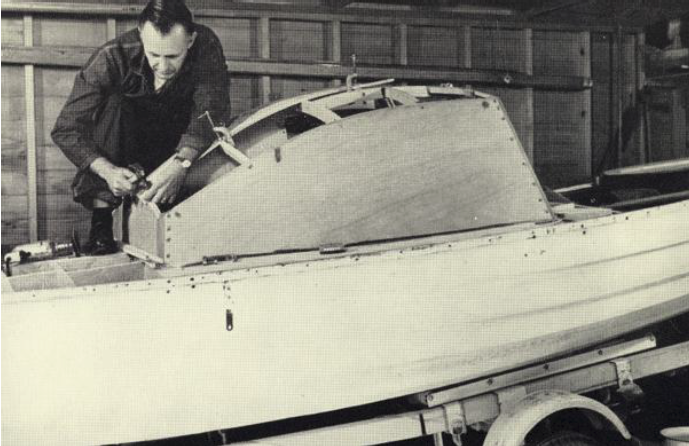

For the next two days I occupied myself aboard Tinkerbelle with moving my stores into what I hoped would be the most convenient arrangement and in lashing them down so firmly that they wouldn’t shift even if the boat was turned over. I also did some last–minute varnishing and worked out a way to carry the oars on either side of the cockpit with their blades extending out beyond the stern of the boat. I wanted them where I could get at them easily, for I might have to put them to use at a moment’s notice.

Once all my gear was packed away as I wanted it, I swung the boat to check the compass. It’s a good thing I did, for I found a substantial error on the east–west heading. However, once it was discovered, it was easily corrected and I gained the satisfaction of knowing that I could then rely on the instrument.

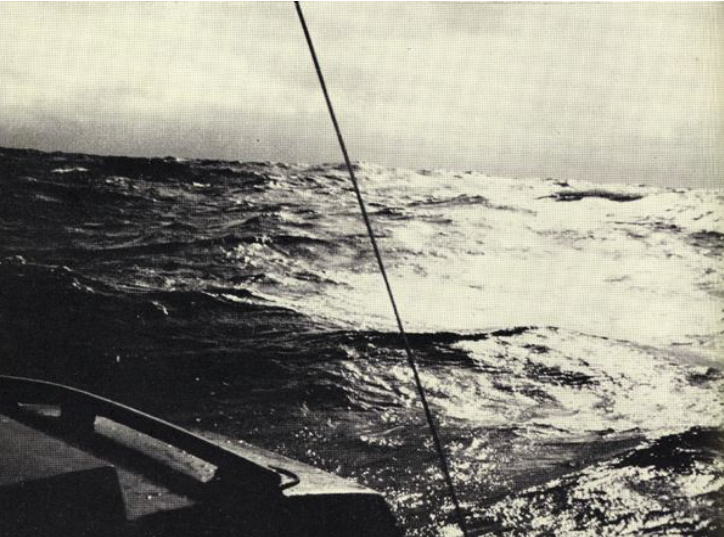

The night of Monday, May 31st, my last night ashore for some time, I had supper at a little restaurant on the city’s main street and, while I was eating, reviewed the circumstances that had led me to select Falmouth as my port of departure. Actually, the first thing I’d done was to choose the port I wanted to arrive at in England and, in the beginning, I’d thought the best one would be Penzance, for it was near a tip of England that stretched out toward the United States like a hand offered to a friend. But the Sailing Directions mentioned various difficulties and dangers connected with entering Penzance, or Newlyn, the adjacent harbor where the Crapos had landed, so I decided to go on to Falmouth, which seemed to have an excellent harbor that could be entered without danger, although there was one sentence in the Sailing Directions that made me a bit nervous “Falmouth experiences a remarkably high number of strong winds and gales.”

I’d just have to hope no gale was blowing when I arrived on the scene. Anyway, I decided to end my voyage at Falmouth, in Cornwall, and it remained only to decide where to start it.

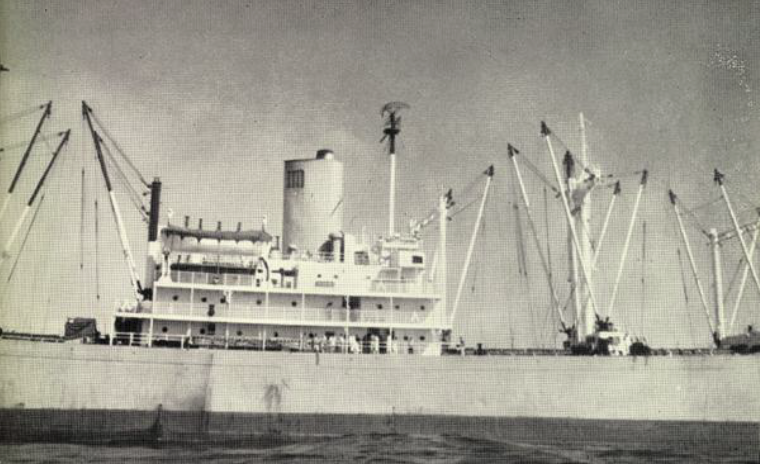

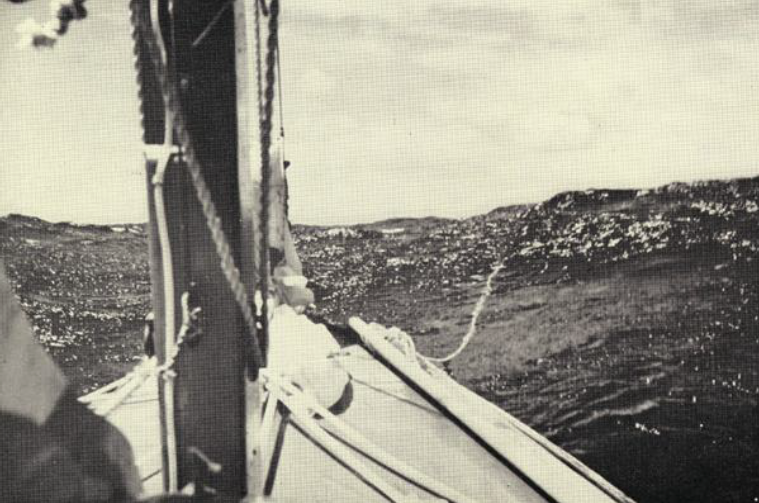

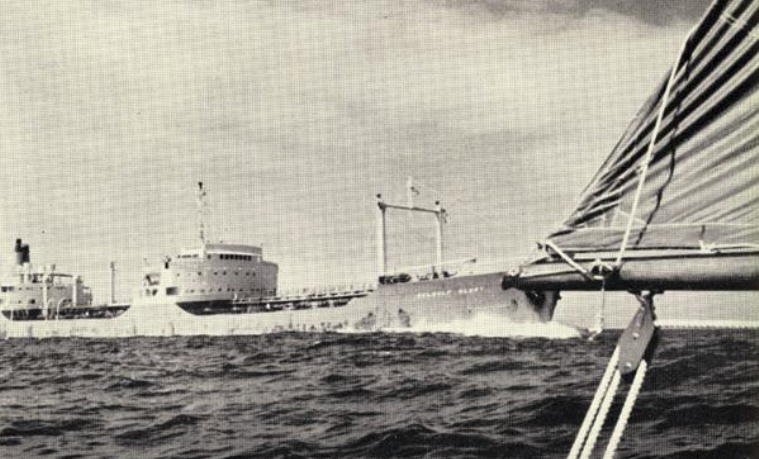

I’d thought I’d best embark at a port from which I could sail southeastward handily to get across the shipping lanes out of New York City as soon as possible. Next to the approach to England, I expected this first part of the voyage to be the most dangerous because of the heavy ship traffic. On studying the map I decided that some harbor on the southern shore of Cape Cod would do very nicely as a starting point and then I discovered a Falmouth there, too. So that settled it. I’d sail from Falmouth, U.S.A., a former shipbuilding center and whaling port, to Falmouth, England, a famous maritime town and resort.

About 9 P.M. I telephoned Willowick and said goodbye to mother, Robin, Douglas and Virginia, all of whom were still confident of my success. As I left the telephone booth and walked slowly back to Tinkerbelle, I was seized by an intense realization of my great good fortune in having a mother and family like mine. How many mothers, sons, daughters and wives were there in the United States or the world who would let their son, father or husband do what I was doing? It struck me that probably there were very few. I’d seen too many men whose lives were hemmed in by strict adherence to the conventional demands of a business or profession or marriage; too many whose lives were pallid by the fear of being different, of being criticized, of failing to meet all their responsibilities (as others saw them). I knew these fears well indeed because I had cringed before them myself. The pressure to conform that pervades our society has a basically useful function, I suppose, but I wonder if it isn’t too intense, too rigid, or perhaps misdirected, so that it stifles the freedom of living that leads to happiness and, incidentally, to an intellectually richer environment for everyone.

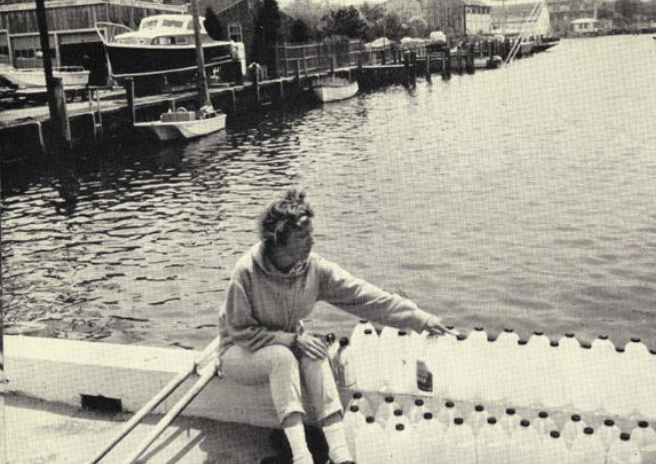

I was positive no one in the world had as wonderful a wife as mine. Virginia’s quiet faith was an extraordinary compliment and a priceless gift such as few men received in their lives from anyone. She could have insisted that I behave as other “rational” men did and give up any notion of taking this “crazy” voyage. But she didn’t. She knew I was stepping to the music of a different drummer and she granted me the invaluable boon of self–realization by allowing me to keep pace with the music I heard. I was poor in dollars and cents, but rich in love. I hoped I would prove worthy.

On the way back to the boat I mailed some letters. One was to the Plain Dealer‘s executive editor and others were to friends on the copy desk, and they all revealed the truth about my voyage: that instead of going with someone else in his 25–foot boat, as I had originally expected to, I was going alone in my own Tinkerbelle. I hoped that no one at the P.D. would think too harshly of me for my deception.

There were also letters for Virginia and close relatives who already knew the facts.

When I got to the dock, Tinkerbelle somehow seemed to be in an expectant mood, as though she knew what was ahead. She was certainly as ready, as prepared, as any boat her size could be. There was just one thing missing. I hadn’t been able to find the chemical shark repellant anywhere and, earlier, on the phone, when I’d mentioned it to Virginia, she had informed me the repellant had accidentally been left at home. It was there now.

“You’ll have to make friends with a dolphin and have him keep the sharks away,” Virginia had said.

I said, yes, I guessed that was what I’d have to do.

It didn’t worry me because I understood the repellant wasn’t especially effective. I’d read a report by a “shark research panel” of Navy and civilian scientists that said the trouble with most shark repellants was that those that worked at all were as likely to attract sharks as to shoo them off. So maybe I was better off without the chemical shark chasers.

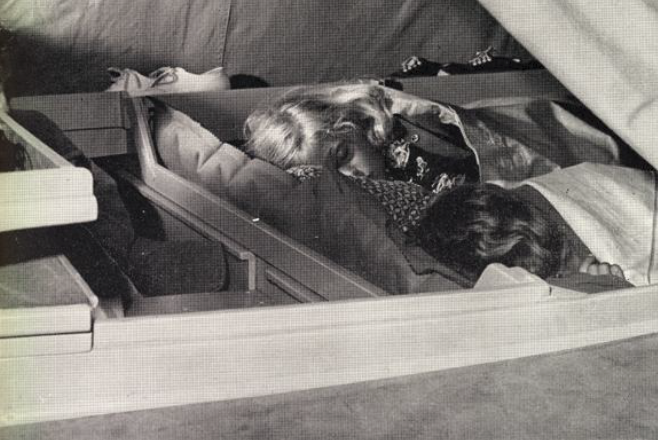

Soon I was in Tinkerbelle‘s cabin, curled up under a blanket. Tomorrow would be a long, hard day of sailing; in fact, I might have to continue sailing for two or three days and nights without sleep to get safely across the shipping lanes. I told myself I’d better get all the rest I could that night, for it was the last one I’d spend in the safety of a harbor for many days to come.