Main Body

Chapter 7

The alarm clock jarred me awake. It was already 9 A.M., broad daylight, and the sun was beating on the deck and cabin roof. Soon the interior of the boat would be an oven. It was time to get moving.

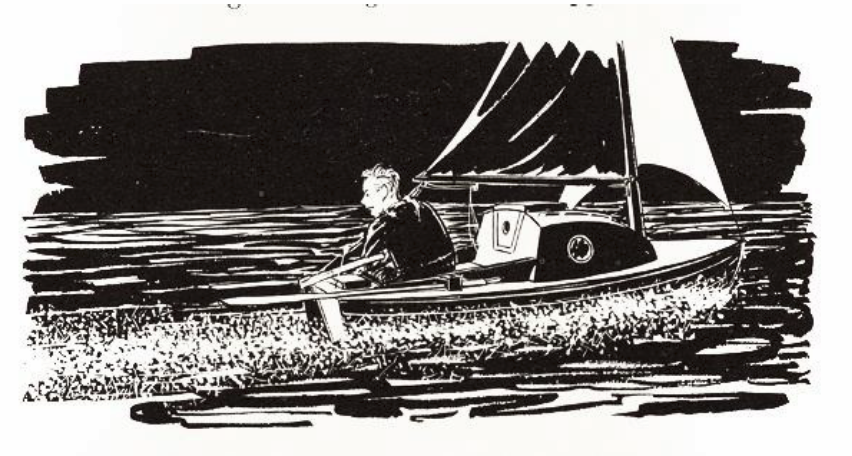

I washed, had breakfast, attended to a few last–minute chores and said a quiet goodbye to Bill Litzkow at the marina. Then, at about ten–thirty, I hoisted Tinkerbelle‘s red mains’l and white genoa and she and I set forth on our great sea adventure.

It was a beautiful day. The sky was dark blue overhead, shading to lighter blue near the earth and sea; it was pleasantly warm, and a gentle breeze caressed Tinkerbelle‘s sails. There was just one little flaw in the otherwise perfect picture: the breeze was from the southwest, which meant we had to tack out of the harbor. But that was a small price to pay for a blue sky and warm sunshine. Fortune was smiling on us.

We skimmed from one side of the harbor to the other, dodging between handsome moored craft, and with each jog we drew closer to the exit into Vineyard Sound, about half a mile away. As we moved along, I saw on our portside a sleek boat owned by Joseph P. Kennedy, former United States ambassador to the country to which we were headed, and off to starboard the fine restaurant where Virginia, her brother and I had had our farewell dinner a few nights before. In a few more minutes we slipped through the rock–lined channel into the sound.

From here it would have been possible to follow the course Crapo had taken in the New Bedford exactly eighty–eight years and one day before and sail directly eastward to Chatham, and then on out into the open ocean. But Crapo’s account of the voyage mentioned his having run aground several times near Chatham, and the United States Coast Pilot for the area contained frightening notations such as: “The channel is used only by small local craft with a smooth sea; strangers should not attempt it. The wreck of the steamer Port Hunter is on the southwestern side of Hedge Fence. Because of the numerous shoals, strong tidal currents, thick fog at certain seasons… the navigator must use more than ordinary care when in these waters.” Consequently, I decided not to follow Crapo’s example.

Another possibility was to sail more or less southward and pass through Muskeget Channel, between Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard islands, to the sea. Here again the Coast Pilot dissuaded me. One ominous sentence said, “Although this channel is partly buoyed, strangers should never attempt it, as tidal currents with velocities of two to five knots at strength make navigation dangerous.”

We couldn’t sail directly east or south, safely. There was just one other possibility and, fortunately, the Coast Pilot had no scary remarks about that. We could continue tacking and go southwestward around the western coast of Martha’s Vineyard and thus reach the open ocean approximately at the point where the meridian of 71° W longitude intersected with the parallel of 41° 22′ N latitude. So that’s what we did.

We beat down Vineyard Sound, passing Nobska Point and, beyond it, Woods Hole, in the early afternoon. I was intrigued by a peninsula on the chart called Penzance, which bore about the same geographical relationship to Falmouth, Massachusetts, that Penzance, England, bore to Falmouth, England.

We had the sound to ourselves all afternoon except for one small trawler that hurried by in the opposite direction as we approached the Elizabeth Islands hilly and partly wooded mounds of sand rising from low shoreside bluffs off to starboard. These islands have fascinating names: Nonamesset, Uncatena, Naushon, Pasque, Weepecket, Nashawena, Penikese and Cuttyhunk, most of them Indian.

I wondered if Cuttyhunk had been named by Bartholomew Gosnold, the English adventurer and explorer who landed there in 1602.

t was he who had named Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, the latter for his daughter and the grapevines he found, so it seemed possible that Cuttyhunk was his idea, too.

It was a pleasant, easy sailing, with a breeze of ten or twelve knots, just enough to keep Tinkerbelle moving along contentedly without any fretting or straining. After a long starboard tack across the sound we came about off Martha’s Vineyard’s Cape Higgon in the late afternoon and headed toward Nashawena. Along the way Tinkerbelle rose and fell to the first big swells coming in from the open sea, and showers of spray shot up from her bow, drenching her foredeck.

“Here we go,” I said.

I don’t believe I had any strong feelings of trepidation. It just seemed that we were out for an enjoyable sail. I knew that probably many rough, uncomfortable days lay ahead, but I felt sure my preparations had been adequate and, more important, I had tremendous faith in my companion, my friend, Tinkerbelle. She was the main reason for my serenity.

A voyage made by a solitary person is sometimes called a singlehanded voyage or a solo voyage, but neither of these terms gives credit to the important factor in any voyage, the boat. Far from being solo, a one–man voyage is a kind of maritime duet in which the boat plays the melody and its skipper plays the harmonic counterpoint. The performances of the boat and the skipper are both important, undeniably, but if it comes to making a choice between the two the decision must be in favor of the boat. For there have been a few honest–to–goodness solo voyages, and these have been made by boats, not men.

I had read about dories from fishing vessels on the Grand Banks occasionally breaking loose with no one aboard, drifting all the way across the Atlantic and being found weeks later on the coast of Ireland or England. But I had never heard of a man accomplishing that feat without a boat.

And there was the famous case of the Columbine, a 50–foot sailing vessel used in the Shetland Islands toward the end of the nineteenth century for trade between the port of Grutness and Lerwick, about twenty miles away. One January day this ship, carrying its skipper, crew of two and a partly paralyzed woman passenger, was bound for Lerwick when the mainsheet broke and the heavy boom began swinging back and forth dangerously as the vessel rolled from side to side. The skipper and the mate tried to retrieve the end of the parted line but a violent lurch threw them into the sea. The mate managed to get back on board, however, and he and the other crewmen, without pausing to consider the consequences, put out in the ship’s dinghy to rescue the skipper. They never found him. And they never got back to the Columbine. They did manage to get ashore, however, and sound the alarm.

The invalid passenger, Betty Mouat, had expected a voyage of less than three hours; instead she got one that lasted more than eight days. And all that time she remained below, unable, because of her paralyzed condition, to get on deck. The Columbine sailed herself all the way across the treacherous North Sea, finally running aground on the island of Lepsoe, north of Alesund, Norway. Betty Mouat was rescued.

So, remembering the incredible voyage of the Columbine, I had no illusions about the relative contributions of Tinkerbelle and myself toward making our cruise a success. Tinkerbelle‘s part would be the greater, by far. I was just there more or less for the ride and to keep her pointed in the right direction.

Near Nashawena we went over onto the starboard tack again and soon we were due west of Gay Head, the westernmost point of Martha’s Vineyard. I could clearly see the headland’s cliffs, topped by a lighthouse, reddened by rays of the magnified sun that was now setting far astern beyond the Elizabeth Islands. “Red sky at night, sailor’s delight.” If that old jingle was right, we’d have good weather the next day. We could use it. We needed it in order to get as far away from shore as possible, as quickly as possible, because, contrary to what many non–seafarers believed, the most dangerous thing about the sea was not the sea but the land. As long as a vessel was in the open sea, with plenty of room around her, she could manage quite well. But if she was unfortunate enough to be blown against the land, perhaps on a rocky coast, she would be smashed like an eggshell. We had to get far enough from land to prevent that from happening to us.

The day was dying in a blaze of glory in the west as we slipped gently out of the womb of Vineyard Sound into the open ocean. Our voyage was born. It was a singularly thrilling moment for me, as moments when dreams are coming true are bound to be. How long had it been since I’d heard that German adventurer speak at Woodstock, creating my vision of an ocean voyage? Twenty–nine years and eleven months, to be exact. That was a long time to cherish an ambition. But think how few of the ambitions of youth are achieved by anyone. One of the tragedies of life is the way teen–age boys and girls have to abandon their bright, happy dreams, one by one, as they grow to adulthood and are forced to cope with the harsh realities of existence. I was fortunate beyond measure.

As we sloshed and splashed out into the dark of the night and the immense space of the ocean, I was swept by a feeling of elation derived partly from the satisfaction of crossing the threshold of a longed–for adventure and partly from an eerie sensation that I was sailing along in the afterglow of history, in the wake of splendid, momentous, exciting events.

These same Cape Cod waters, it was said, had been plied by Vikings about the year 1000, and by French and Spanish fishermen in the fourteen–hundreds. Historians believed John Cabot, an Italian sea captain employed by England, probably sailed along the Massachusetts coast in 1498 and, after him, Giovanni da Verrazano, an Italian navigator and pirate, who entered what is now New York Harbor and discovered the Hudson River in 1524. Then came Gosnold, and then another Englishman, Henry Hudson, who was employed by the Dutch and who, in 1609, sailed his ship, the Half Moon, up the river that bears his name.

Still another Englishman, Captain John Smith, arrived on the scene in 1614, explored the Massachusetts coast and drew maps of it that seamen used for many years thereafter.

The waters we were passing through had been alive with whalers, packets, down–easters, schooners, and those beautiful, trim greyhounds of the sea, the clippers, in the eighteen–hundreds. But then came steam power to drive these lovely sailing craft out of commerce. Praise be the Lord, though, sails had not been banished altogether from twentieth–century America. They lived on, mostly in pleasure boats of varying types and sizes, and I hoped they would continue to do so. I tried to picture a world without tall masts raking the sky, without gracefully curving, wind–filled sails, and what I saw was dismal.

Behind us now, on the other side of the Elizabeth Islands, was Buzzards Bay, where the doughty Joshua Slocum had taken his first trial run in the Spray before proceeding to Boston to begin his historic globe–girdling voyage. The waves of Buzzards Bay also had been parted by the 20–foot Nova Esperoas Stanley Smith and Charles Violet neared the end of their voyage from London to New York, and by the famous 96–foot Yankee in which Irving and Electa Johnson had cruised the world with amateur crews. And New York, a short sail to the southwest, had been the terminus of one of the most nearly flawless small–boat voyages on record, the classic cruise from England of Patrick Ellam and Colin Mudie in the 19 ½ foot Sopranino. There, too, had ended fine voyages of the Frenchman Alain Gerbault in the 39–foot Firecrest and the Englishman Edward Allcard in the 34–foot Temptress. In fact, that part of the ocean had been crisscrossed by the tracks of innumerable small sailboats, some of them participants in recent singlehanded trans–atlantic races.

In the midst of these musings I felt a pang of hunger and realized I hadn’t eaten anything since breakfast. I reached into the cabin, got myself a meat bar and munched on it as we continued on our way. I didn’t want to stop to warm up some food because we had to keep moving offshore as quickly as we could and also across the shipping lanes leading eastward out of New York. I knew I wouldn’t be able to sleep safely until we were well south of these lanes.

As we sailed southeastward on a course of 157°, we had the wind just a few degrees forward of the starboard beam, so we were able to make good time. Tinkerbelle frisked along like an energetic colt and gave me my first clear view of the pyrotechnic display put on at night by phosphorescent plankton and other minute oceanic creatures. I watched bewitched, for it was a spectacular show. The water ruffled by the boat’s passage glittered and shone with a starry fire. Tinkerbelle appeared to be floating on a magic carpet of Fourth of July sparklers more brilliant than any I’d ever seen, and trailing behind her was a luminescent wake resembling the burning tail of a comet.

Spray at the bow occasionally tossed onto the foredeck tiny jewels of light that winked for a few seconds and then went out, only to be replaced by other blinking gleams. An examination by flashlight of the spot where a kernel of radiance was last seen sometimes revealed a microscopic blob resembling a fish and sometimes a fibrous mass that looked like a tuft of matted wool from someone’s sweater. How such unlikely organisms could produce bright glints of light was, no doubt, a mystery that someday would be unraveled. Perhaps the phenomenon had already been explained without my having learned of it. That didn’t make it any less wondrous.

It was a dark night and it rapidly grew darker as a curtain of clouds moved across the sky, screening off the stars’ light; but I didn’t mind, for the darkness made the phosphorescent sorcery of the sea appear even brighter, more enchanting. Although I couldn’t see it, I knew from the chart that we were passing, off to port, the small island of No Mans Land. The breeze was holding up well and we were stepping along smartly. Soon the last lighted navigation aids disappeared from view and we were alone in darkness relieved only by the warm glow of the compass light and the fireworks in the water. It was eerie. And it was beautiful.

We must have been well to the southeast of No Mans Land when I looked at my watch. It was 2 A.M. The new day, the second of our voyage, was already two hours old. It was Wednesday, June 2nd, my birthday, and I was forty–seven, ten years older than Tinkerbelle, who was no spring chicken. According to the statistics, I was headed down the sunset trail, past the milestones of middle age, but somehow I didn’t feel ancient enough to be on that particular trail just yet. Life was supposed to begin at forty. If that was true, Tinkerbelle was beginning her life early and I was seven years late getting across the starting line. No matter. Better late than never.

We kept moving all night and through the morning of what turned out to be a cloudy day. No land was in sight. I ate a cold breakfast so I wouldn’t have to stop to prepare anything, but shortly after noon the wind died and we came to a halt anyway. The ocean was a gray sheet of glass.

I’d never seen it so placid, so flat, so motionless. It had an otherworldly quality.

Since we couldn’t move, having no wind, and since I was tired, having had no sleep for more than twenty–four hours, it seemed an appropriate time to get some rest. So, leaving the red mains’l up to render Tinkerbelle highly visible to any ships that might approach, I stretched out in the cockpit as best I could for forty winks. It wasn’t a particularly comfortable place for a nap, but I was fearful of sleeping in the cabin. I thought I might sleep too soundly there and fail to awake promptly if a breeze sprang up suddenly.

I slept longer and more soundly than I wished. It was about 2:30 P.M. when I awoke and found, to my dismay, that we still had no breeze and, worse, that we were surrounded by dense fog. We couldn’t move, and I couldn’t see beyond a few feet. Nor could the red mains’l now warn passing ships of our presence. A ship could run us down without even knowing it. I hoisted the radar reflector to warn at least radar–equipped vessels of our presence, and I got out the oars to be ready to row for my life if a vessel should slice out of the fog directly toward us. I also got out the compressed–gas foghorn and sounded it from time to time. There were no answers. In fact, there were no sounds at all, except those we made ourselves. And the fog seemed to intensify these, reflecting them back to us. It was spooky.

In an hour or two a very light breeze came along and I put away the oars. We had just enough wind power to maintain steerageway. That was a slight improvement. And every now and then it rained for a few minutes, clearing the fog a little. That helped, too. But as soon as it stopped raining, the fog returned, becoming as thick as before. It gave me a closed–in feeling that must have been related to claustrophobia. I was decidedly uneasy, for we were obviously in a rather ticklish situation. And when I began to hear ships passing by it didn’t help to calm my nerves.

I was surprised at the intensity and variety of the sounds produced by these passing ships, and by the speed at which they traveled invisibly through the fog. And most surprising of all, few of them blew their foghorns–at least, not regularly. Some of them throbbed by so close I could hear their bow waves breaking and, if they were traveling light, their propellers chopping the water. Several times I expected to see one come charging out of the fog on top of me, but I never even saw the dim outline of one; not just then, anyway. I’ll never forget one of those ships, however. It passed by with music from a radio or phonograph, amplified through a loudspeaker, blaring out across the sea. That music was as effective as a foghorn. It was so loud it seemed entirely possible that even the people ashore on Martha’s Vineyard, thirty-five or forty miles away, could hear it.

According to my dead reckoning, we were down approximately to the latitude of the Nantucket Shoals Lightship and about thirty miles west of it. This put us very close to the shipping lanes between New York and Europe, which was undoubtedly why I heard so many vessels going by. We were in an area where numerous shipping disasters had occurred and I hoped that we wouldn’t be added to the list of casualties.

Somewhere in these waters, in January, 1909, the White Star liner Republic had been rammed and sunk by the Italian ship Florida. However, all but six of the Republic‘s passengers had been saved by a CQD (this was before SOS came into use) sent out by the doomed vessel’s wireless operator, Jack Binns. It was the first time radio had ever been used in a sea rescue.

Also nearby was the final resting place of the Italian luxury liner Andrea Doria, which, on July 15, 1956, had sunk with the loss of fifty–one lives after colliding with the Swedish ship Stockholm. I wondered if the ghost of the Genoese admiral after whom the Andrea Doria had been named was keeping watch over his sunken namesake. He had been a great sea captain; as great as the other son of Genoa, Columbus, some said. He was credited with making it safe for seamen to sail against the wind. In the early sixteen–hundreds hardly anyone dared to do so because whoever did risked being burnt alive as a wizard. Seafarers almost always waited for a favorable wind from astern before leaving port, but Admiral Andrea Doria flouted this prejudice. He tacked against the wind whenever he chose and his enormous prestige preserved him from the wrath of the superstitious.

The admiral, who lived to be ninety–four, must have been a grand old sea dog. If his spirit was in the vicinity, I hoped some of his strong character would brush off onto me. I wouldn’t need much of his talent for going against the wind, though, because, on a course for England the prevailing winds were westerlies. We wouldn’t have to do much tacking.

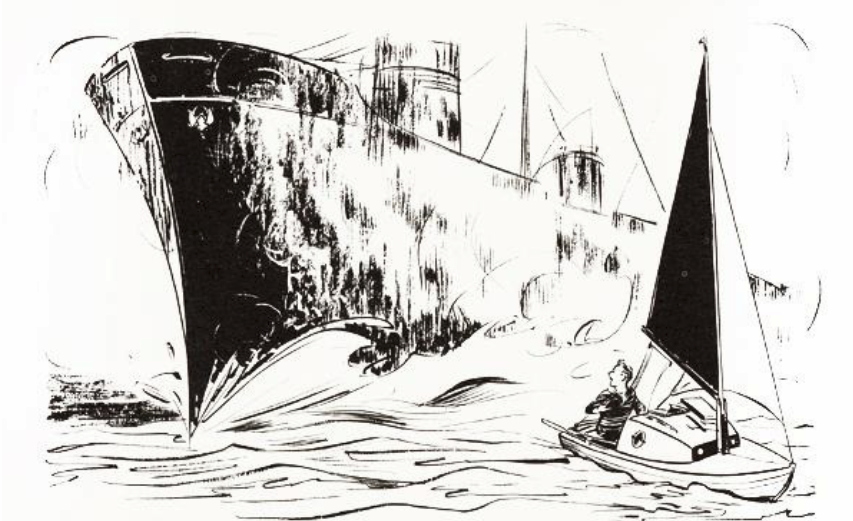

Just then a mammoth black apparition with steel masts, funnel and hull slid out of the fog off our port quarter and, apparently seeing Tinkerbelle‘s red mains’l, let go with a tooth–rattling blast on its steam horn that made me jump with such an involuntary vigor I nearly fell overboard. What did a single blast on a ship’s horn mean? And what was the appropriate reply? I wasn’t sure and there was not time to look it up in my book. I thought I recalled, though, that the signal for a sailing vessel becalmed in fog was three blasts on the horn, so that’s what I sounded. We weren’t totally becalmed, of course, but we were so close to it that I thought we might as well ignore the difference and, anyway, at that particular moment I couldn’t think of any other signal more suited to our circumstances. Luckily, it worked out all right; at least the ship, on a course to pass a comfortable distance astern of us, stayed on that course and didn’t change to a course leading straight for us. A minute or two later, when it had disappeared back into the mist and my heartbeats had slowed to their normal pace, I got out my book and found that the signal I’d given was for “wind abaft the beam.” I really hadn’t made a liar out of myself, though, because the wind (what little we had) was abaft the beam. However, it was plain to see that I needed to review the rules for horn signaling in fog.

The skipper of that freighter, the only ship I saw all that day, probably shook his head and said, “Why the heck do amateurs have to clutter up the ocean?”

Shortly after nightfall the breeze picked up and we began moving again at a more satisfying pace. At about 2 A.M. it rained very hard, dispersing the fog. Off to port I saw bright lights which I took to be ships, and one especially bright point of illumination, which, since it was stationary, I decided must be a large buoy serving to guide ships toward New York. Tinkerbelle and I passed several miles to the south of it and, soon afterward, were overtaken by a violent thunderstorm. The flashes of lightning and crashes of thunder made me thankful for the lightning rod at the masthead, although I earnestly hoped it wouldn’t be put to use.

The noisy commotion in the sky passed quickly, fortunately, but then the wind freshened and, almost before I could get the sails down, it was blowing at what seemed to me to be gale force, forty or forty–five miles an hour, and, again, raining very hard.

We were in for it. I crawled to the foredeck, holding firmly onto the bounding boat while I put out the sea anchor as speedily as I could.

Our sea anchor was an army–type canvas bucket. It was streamed from the bow on a hundred and fifty feet of half–inch nylon line, with a polyethylene float attached to it by another, much lighter line to keep it from sinking farther than fifteen feet below the surface. Its function was to act as a brake, and to hold the bow facing into the wind and the waves as the boat, its sails doused, drifted slowly sternward. This was the safest way for a small boat, especially a boat with Tinkerbelle‘s underwater shape, to weather a storm.

Although I’m ashamed to admit it, I must state that this was the first time I’d ever had Tinkerbelle tethered to a sea anchor, so I was afraid she wouldn’t respond as I hoped she would, by facing into the wind and waves. In less than a minute it became apparent that my fears were well founded; she didn’t face the waves, she turned her side to them. That posture meant calamity, for she could be bowled over by a breaker. What should I do? I didn’t know for sure; all I knew was that, whatever it was, it had to be done soon.

The rudder! It extended deep into the water; it must be the cause of the trouble, I thought. So I took it off and stowed it securely in the daggerboard–keel slot. That was the right thing to do, for Tinkerbelle immediately swung around and faced the waves. Her motion became less frantic, easier, smoother. She began to look after herself, enabling me to think about something besides the basic necessity of keeping her upright.

Since the wind was blowing from the northwest, we were drifting slowly toward the southeast, the same direction in which we had been sailing. That was providential, for we were moving farther into the open sea, away from the land and its terrible dangers.

Lights appeared astern and drew closer and closer as Tinkerbelle drifted. Were they buoys, or were they ships, or were they something else? I couldn’t be sure because the pelting rain obscured my vision, but I thought most probably they were small ships. In any case, one fact was clear; it would be wise to avoid contact with them. So I got out an oar, put it into the oarlock I’d fixed at the stern for just such an occasion as this and, by rowing one way or the other, controlled the direction of our drift sufficiently to prevent collision with the lighted objects. I never did find out what they were, but in an hour or so we were safely through them with nothing but blessedly black ocean beyond. And to make the situation even better, the rain stopped. Glory be! Now I really could relax a little.

Sitting toward the rear of the cockpit and looking forward into the wind, I saw staggered ribbons of phosphorescent wave crests bearing down on us. The entire sea, from the port beam all the way around to the starboard beam, was filled with graceful, undulating, luminous forms. It was a spectacularly beautiful sight. It would have been a most enjoyable one, too, if it hadn’t been for the danger; for as I assessed our predicament that night, as Tinkerbelle and I rode out our first full-fledged storm, any one of those waves could have been lethal if it had broken at exactly the wrong moment and had caught Tinkerbelle in exactly the wrong position.

Yes, every wave was a potential disaster, but I was relieved to discover that, in the midst of those acres and acres of crashing thundering breakers, very, very few waves broke at precisely the moment when we were in their path. The great majority broke either before or after they reached us. And they came in cycles. We would ride up and down average–sized waves for several minutes and then along would come a group of four or six much larger waves. Then we’d have another few minutes of average–sized fellows, and then another batch of whoppers. It continued like that, on and on.

And Tinkerbelle always seemed to be ready for those few waves (maybe one every ten minutes or so) that broke at the wrong moment and slapped against her. She met them like a trouper, head–on, and rode over them with a jounce that gave me the impression of being in the saddle of a bronco.

Measuring the waves as well as I could against Tinkerbelle‘s eighteen–foot mast, I estimated the biggest ones we met were ten or twelve feet high, from trough to crest. These were not monsters, as waves go, but they were definitely bigger than any waves either of us had experienced before at such close quarters. At the beginning of the storm they were especially ominous because they seemed to be steeper then than they were later on. As the wind continued, it seemed as though the waves grew bigger and, at the time, more rounded, somewhat as if new, sharply pointed mountain peaks were, in an hour or two, ground down by the erosive forces of geological ages and at the same time elevated to new heights by diastrophic movement on the earth’s crust.

At long last the sky began to fill with light and, at about the same time, the sea grew less tempestuous. It appeared that Tinkerbelle and I were going to get through our first big oceanic crisis without mishap. Well, not exactly without mishap because when I looked up I found that sometime during the night the radar reflector had shaken loose from the masthead and was gone forever. I could have kicked myself for not securing it more firmly, and for not bringing along a spare. All right, so it was gone. We’d just have to do the best we could without it.

During the half–light between night and day I had a moment of fright when a small vessel, probably a trawler, passed too closely astern for comfort, apparently without any knowledge of our presence. No one appeared on the deck of the ship, which remained on an unswerving southwestward course and soon was out of sight over the horizon. Tinkerbelle and I once more had the ocean to ourselves.

My little boat rode the waves as gracefully as a gull: up, over and down, up, over and down, up, over and down. I was pleased beyond words, as proud of her as I could be. I patted her cockpit and told her, “Good going!”