Part 4: Indian Sub-Continent Origins

4.5 Sikhism

The Sikhs are a later development in the Dharmic traditions, and came about through one man, initially, Guru Nanak. Gurus are central to Sikh beliefs and values, and there are 10 that were followed in the beginning as this tradition developed.

Getting Started: a little history and background

An overview of the founding of the Sikh religion started by Guru Nanak.

We then use materials from a number of articles written by Eleanor Nesbitt [1], through the British Library Sacred Texts site:

” There are currently about 24 million Sikhs worldwide. The majority live in the Indian state of Punjab. They regard Guru Nanak (1469–1539 CE) as the founder of their faith and Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708 CE), the tenth Guru, as the Guru who formalized their religion. Religions and religious teachers do not exist in a vacuum: India, in the Gurus’ time, was ruled by Mughal emperors who were Muslim. Punjabi society was a mix of Muslims and Hindus.

The Sikh religion has evolved from the Gurus’ teachings, and from their followers’ devotion, into a world religion with its own scripture, code of discipline, gurdwaras (places of worship), festivals and life cycle rites and Sikhs share in a strong sense of identity and celebrate their distinctive history.

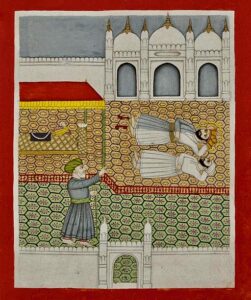

A central principle of the Gurus’ teaching is the importance of integrating spirituality with carrying out one’s responsibilities. Sikhs should perform seva (voluntary service of others) while at the same time practicing simaran (remembrance of God). The ideal is to be a sant sipahi (warrior saint) i.e. a person who combines spiritual qualities with a readiness for courageous action. Guru Nanak, the first Guru, and Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Guru, continue to feature prominently in Sikhs’ experience of their religion.

Who was Guru Nanak?

Guru Nanak was born in 1469 in Talvandi, a place now renamed Nankana Sahib, in the state of Punjab in present-day Pakistan. His parents were Hindus and they were Khatri by caste, which meant that they had a family tradition of account-keeping. The name ‘Nanak’, like Nanaki, his sister’s name, may indicate that they were born in their mother’s parents’ home, known in Punjabi as their nanake. Guru Nanak’s wife was called Sulakhani and she bore two sons. Until a life-changing religious experience, Nanak was employed as a store keeper for the local Muslim governor.

One day, when he was about thirty, he experienced being swept into God’s presence, while he was having his daily bath in the river. The result was that he gave away his possessions and began his life’s work of communicating his spiritual insights. This he did by composing poetic compositions which he sang to the accompaniment of a rabab, the stringed instrument that his Muslim travelling companion, Mardana, played. After travelling extensively Guru Nanak settled down, gathering a community of disciples (Sikhs) around him, in a place known as Kartarpur (‘Creator Town’).

Guru Nanak’s poems (or shabads) in the Guru Granth Sahib (scripture) give a clear sense of his awareness of there being one supreme reality (ik oankar) behind the world’s many phenomena. His shabads emphasize the need for integrity rather than outward displays of being religious, plus the importance of being mindful of God’s name (nam) and being generous to others through dan (pronounced like the English word ‘darn’) i.e. giving to others. His poems are rich in word-pictures of animals and birds and human activities such as farming and commerce.

Example of the central concept in Guru Nanak’s ideas

Watch this story by Jagjit Singh from the organization “Zero Hunger with Langar” about his meeting with a Muslim Imam in a village in Africa. Sharing Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s simple message of One God and Many paths, and respecting ALL. Be the best you Sikh, Muslim, Christian, Hindu, Jew you can be!

Guru Nanak’s importance results not just from his inspirational teaching but also from the practical basis he provided for a new religious movement: he established a community of his followers in Kartarpur and he appointed a successor, Guru Angad, on the basis of his devoted service. Guru Nanak is respected as ‘Baba Nanak’ by Punjabi Muslims as well as by Sikhs and Punjabi Hindus.

Each year Sikhs celebrate his birthday on the day of the full moon in November. Like other gurpurabs (festivals commemorating a Guru) it is marked by an akhand path (pronounced like ‘part’), a 48-hour, continuous, complete reading of the Guru Granth Sahib which ends on the festival morning. Commemorative events in 2019 celebrated the 550th anniversary of Guru Nanak’s birth.

What is the concept of Guru in Sikhism?

At first Nanak was called ‘Baba Nanak’, with ‘Baba’ being an affectionate term, like ‘grandfather’, for an older man. These days he is better known as Guru Nanak. Just as the word ‘Sikh’ means learner, so ‘Guru’ means teacher.

Key Takeaway

“Just as the word ‘Sikh’ means learner, so ‘Guru’ means teacher. ”

Sikhs explain ‘Guru’ as meaning ‘remover of darkness’. There have been just ten human Gurus. Their lives spanned the period from Nanak’s birth in 1469 to the passing away of Guru Gobind Singh in 1708. Since then the Sikhs’ living Guru has been the Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred volume of scripture. The Guru Granth Sahib is much more than a book: it is believed to embody the Guru as well as containing compositions by six of the ten Gurus. The preeminent Guru (Nanak’s Guru) is God, whose many names include ‘Satguru’ (the true Guru) and ‘Waheguru’ (a name which began as an exclamation of praise).

Centrality of the Guru Granth Sahib

The Guru Granth Sahib is the sacred text of the Sikh community and the embodiment of the Guru. It is central to the lives of devout Sikhs, both in the sense of being physically present in the gurdwara (place of worship) and as Sikhs’ ultimate spiritual authority. Moreover, each day devout Sikhs hear or recite the scriptural passages that constitute their daily prayers and the Guru Granth Sahib also plays an integral part in life cycle rites and festivals.

As the Granth Sahib is Sikhs’ spiritual teacher, their Guru, it is honored as a sovereign used to be, centuries ago in India. The 1430-page volume is enthroned under a canopy and it reposes on cushions on the palki (literally palanquin i.e. the special stand). An attendant waves a chauri above it when it is open and being read: the chauri is a fan consisting of yak tail hair set in a wooden handle. When not being read, the volume is covered by red and gold cloths known as rumalas, and in many gurdwaras, after the late evening prayer, it is ceremonially carried to a special bedroom where it is laid to rest.

Those Sikhs who keep the Guru Granth Sahib at home honor it in a room of its own. If a copy is temporarily housed in a Sikh’s home for the duration of a path (reading of the entire volume) strict rules are observed – for example no non-vegetarian food is kept or cooked. In other words, the house is temporarily a gurdwara.

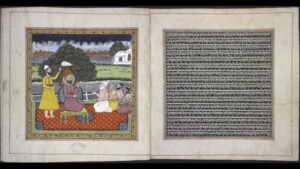

Example of the Guru Granth Sahib

The sheer size of the Gurū Granth Sāhib and the rituals that are observed when it is enthroned and opened for recitation, make for difficulties in its use as a book of private devotion. From quite early on it therefore became common to compile gutke or short anthologies of the principal hymns, the best-known being those called pañj-granthī, containing five major hymns. Over time other hymns were also added.

This gutkā (anthology) was prepared between 1828–1830 for Mahārānī Jind Kaur, popularly known as Rānī Jindān (1817–1863). It consists of three compositions from the Gurū Granth Sāhib, beginning with Gurū Nānak’s Sidh Gosṭi, followed by Bāvan Akharī and Sukhmanī, two compositions by the fifth spiritual master of the Sikhs, Gurū Arjan.

Sikhs believe that all ten human Gurus embodied the same spirit of Guruship and that their different styles were appropriate to the differing circumstances in which they lived. Guru Nanak’s first four successors, Guru Angad Dev, Guru Amar Das, Guru Ram Das and Guru Arjan Dev, were also poets. Their compositions, together with Guru Nanak’s, became the basis of the Guru Granth Sahib. While their spiritual emphasis seamlessly continued Guru Nanak’s, each made a distinctive contribution to Sikh community life. Guru Angad formalized the Gurmukhi script in which the scripture is written. It was almost certainly developed from the shorthand that accountants used for keeping their accounts, as a simpler version of the script that is still used for the older language of Sanskrit.

Sikhs turn to the Guru Granth Sahib for guidance when they face a dilemma. The time-honored method is for the volume to be opened at random and for the words of the hymn at the top of the left-hand page to be taken as the Guru’s response. This guidance is called a vak. A vak is taken each day in all gurdwaras and the words are displayed for everyone to read.

Life Style Features of Sikh Life

Guru Amar Das made the langar a key feature of Sikh life: a shared vegetarian meal eaten by people of all ranks sitting together regardless of their social status. His other innovations included setting up a Sikh place of pilgrimage and appointing preachers to lead local Sikh congregations. His son-in-law and successor, Guru Ram Das appointed stewards-cum-missionaries to organize worship and collect offerings and he started the settlement which in due course was renamed Amritsar.

In observant Sikh families a child’s name is chosen on the basis of a vak, as the first word of the hymn on the left-hand page provides the initial for the infant’s given name. So, if the first word began with ‘s’, names such as Sukhvinder, Satnam and Simran might be considered. Most Sikh forenames are unisex: in a boy’s case his name will be announced as, for example, ‘Satnam Singh’ while a girl would be ‘Satnam Kaur’.

The Guru Granth Sahib is literally at the heart of the rite of anand karaj (marriage), as – linked by a scarf that hangs over the groom’s

right shoulder – the couple walk around it clockwise four times, with the groom leading the way and the bride following close behind him. She is helped on her way by her close male relatives. Before each round, the officiant reads one stanza of Guru Ram Das’s hymn entitled Lavan (Guru Granth Sahib, page 773) and the ragis (musicians) sing this again as the bridegroom precedes the bride around the palki. The stanzas of the Lavan evoke the progress of the human soul and the enthroned scripture is witness to the marriage. The service concludes with six verses of Anand Sahib (Guru Amar Das’s composition on pages 917-922 of Guru Granth Sahib), followed by the Ardas (congregational prayer) and a distribution of karah prasad (made from ghee, sugar, wheat flour and water).

At a Sikh’s funeral, the late evening prayers (kirtan sohilla) are recited and, following someone’s death, the entire Guru Granth Sahib is read over a period of up to ten days (this is known as a sahaj path or sadharan path). The ashes of the deceased person are immersed in a river – in many cases the river Satluj at the town of Kiratpur in north India.

Sikh Worship

Sikhs worship in Gurdwaras.

A gurdwara is a building in which Sikhs gather for congregational worship. However, wherever the Guru Granth Sahib is installed is a sacred place for Sikhs, whether this is a room in a private house or a gurdwara. The word is often translated as ‘doorway to the Guru’ and it means the place in which the Guru, embodied in the Guru Granth Sahib, is resident and honoured. In the 18th and 19th centuries the word gurdwara gradually replaced the earlier term ‘dharamsala’ for rooms used for religious purposes during the Gurus’ lifetimes.

There are gurdwaras in every country where Sikh communities have settled. In the UK alone there are probably about 300 gurdwaras. In the early years of Sikh settlement in the UK, rented premises served as gurdwaras. The next stage was to purchase a building and modify it for Sikh worship. An increasing number of gurdwaras are purpose-built, with architectural features inspired by historic gurdwaras in India.

In a gurdwara both men and women must wear a head covering to show their respect for the Guru Granth Sahib and footwear must be removed on entering the building. No tobacco or non-vegetarian food is allowed inside and no-one may enter under the influence of alcohol. In the worship hall it is respectful to bow before the enthroned Guru Granth Sahib and then sit on the floor, cross-legged and facing the Guru Granth Sahib.

Most of the Sikh historic gurdwaras are in north India though some are in Pakistan. (In the Gurus’ time, and until 1947, the Punjab region was not bisected by a national frontier, as Pakistan had not been created.) The architecture of major historic gurdwaras, involving fluted cupolas (gumbads), is influenced by Mughal style. Famous gurdwaras in Pakistan commemorate Guru Nanak’s life: in Nankana Sahib a gurdwara marks the place where he was born and at Kartarpur Sahib a gurdwara stands where he founded a settlement and (in 1539) passed away. Equally well-known is Panja Sahib gurdwara in Hasan Abdal (about 40 kilometres north-west of Islamabad), where a rock bears what is believed to be the imprint of Guru Nanak’s hand.

The title ‘sahib’ in the names of cities (e.g. Anandpur Sahib) and major gurdwaras expresses Sikhs’ reverence for locations associated with their Gurus’ lives.

Five notable gurdwaras in India are known as takhts: takht means throne or seat of authority.

Example of a Gurdwara: HARIMANDIR SAHIB(Golden_Temple)

Sikhs emphasize the fact that Harmandir Sahib has entrances on all four sides, reminding them that the gurdwara is open to every sort of person. This symbolises a Sikh commitment to equality regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. According to tradition, at Guru Arjan Dev’s invitation, a pir (Muslim spiritual master) laid the gurdwara’s foundation stone, so affirming inter-religious friendship.

The Akal Takht (‘throne of the Timeless One’) is in Amritsar (Punjab), facing the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple), and it is the highest seat of authority. The Akal Takht was first established by Guru Hargobind and the two nishan sahibs (pennants flying from flagpoles, honored and clad in orange cloth) are a reminder of his two swords that signified the principle of miri piri (a balance of worldly and spiritual authority).

What are the Sikh festivals?

The Sikh religious calendar consists of melas (literally ‘fairs’) and gurpurabs (anniversaries of Gurus). The Vaisakhi festival in April is the

most important mela, a commemoration of the founding of the Khalsa in 1699 at the first khande di pahul on what was already a spring harvest day in the calendar of Punjabi celebrations. Notable gurpurabs are the birthdays of Guru Nanak (celebrated on the day of the November full moon) and Guru Gobind Singh; the shahidi (martyrdom) days of Guru Arjan and Guru Teg Bahadar and the anniversary of the day when the Guru Granth Sahib was installed in the Harmandir Sahib.

Until recent years Sikh festivals were observed according to the north Indian Bikrami calendar. As most anniversaries were determined by the phase of the moon, the date would vary each year by the secular western calendar. In the 21st century many Sikhs instead follow the Nanakshahi calendar in which most festivals’ dates have a fixed date according to the secular calendar.

48 hours before the morning of the festival, an akhand path begins. On major festivals there is an extended kirtan in the gurdwara and, in some cities, Vaisakhi or the birthday of Guru Gobind Singh may be celebrated with a nagar kirtan. This means that the Guru Granth Sahib, duly enthroned and attended, is driven slowly through the streets. Panj piare, dressed in orange, blue or white, provide the vanguard and hundreds or thousands of Sikhs follow in joyful procession, while refreshments are offered to the walkers by volunteers along the route.

The evolution of a religion…from the Khan Academy

Listening to a modern Sikh woman talk about love.

Nesbitt, Eleanor. “Origins and Development of Sikh Faith: The Gurus.” The British Library:Discovering Sacred Texts, The British Library, 3 Dec. 2018, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/origins-and-development-of-sikh-faith-the-gurus.

Nesbitt, Eleanor. “Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction | Eleanor Nesbitt.” A Very Short Introduction: Oxford Press, Oxford Press, 23 June 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNPhLQmR5W0.

“Guru Nanak’s Universal Message in 60 Seconds!” Sikhnet.com, YouTube, 26 Nov. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=RfcBI_cXe74.

Nesbitt, Eleanor. “Sikh Prayer and Worship.” The British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts, The British Library, 3 Dec. 2018, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/sikh-prayer-and-worship.

Nesbitt, Eleanor. “Sikh Sacred Places.” The British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts, The British Library, 17 May 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/sikh-sacred-places.

“3 Lessons of Revolutionary Love in a Time of Rage | Valarie Kaur.” Ted Talks, 5 Mar. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ErKrSyUpEo.

“Sikhism Introduction.” Khan Academy: Sikhism Introduction, Khan Academy, 2021, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/world-history/renaissance-and-reformation/sikhism/v/sikhism-introduction-khan-academy-world-history.

“Continuity: Connections to Hinduism and Islam.” Khan Academy: Sikh Connections to Hinduism and Islam, Khan Academy, 2021, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/world-history/renaissance-and-reformation/sikhism/v/continuity-sikhism-connections-to-hinduism-and-islam.

- Written by Eleanor Nesbitt Eleanor Nesbitt is Professor Emerita (Religions and Education) at the University of Warwick. Her ethnographic studies have focused on Christian, Hindu, Sikh and 'mixed-faith' families in the UK. She has published extensively on Hindu and Sikh communities. Her recent publications include: Sikhism A Very Short Introduction (2nd edn 2016, Oxford University Press) and (with Kailash Puri) Pool of Life: The Autobiography of a Punjabi Agony Aunt (2013, Sussex Academic Press). She is co-editor of Brill's Encyclopedia of Sikhism and her forthcoming publication is Sikh: Two Centuries of Western Women's Art and Writing (2020, Kashi Books). ↵