Part I: The Arabs: Their History and Heritage

Chapter 1: Phoenician Trade and Travel

Who are the Arabs? The Arabs and the Arab Americans are those people whose ancestors were the Canaanites, the Phoenicians (the western branch of the Canaanites) the Hittites, Amorites, Ammonites, Moabites, Semites; the Sumerians, Arameans, Chaldeans, Hurrians, Horites and Hyksos; the Philistines, for whom Palestine was named, and the Habiru (Hebrews). These were the tribes who came and went in the earliest days of recorded civilization, established thriving kingdoms and advanced cultures, and built cities in the lands of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Assyria, Palestine, Phoenicia and Syria.

As the peoples of the world today cannot realistically trace their lineage or race to a single source, neither could the ancients of those lands, whose geneology had already become well homogenized by the time the world’s oldest city was built, about seven thousand years ago, in that Canaanite land known today as Lebanon. The Egyptians called this city Kupna, the Hebrews said “Gebal” (mountain), and the Greeks came to know it as Byblos, the name it bears to this day.

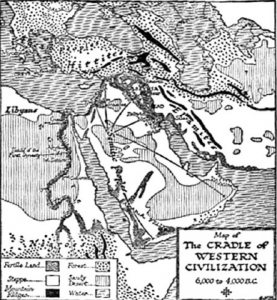

If we trace modern man’s history back to about 5000 B.C., we find that the world was already in a ferment of motion. Shepherds grazed their flocks over as much of the land as they could travel and whole tribes would set forth periodically with their belongings and animals, carts and watering vessels, and their young and their old. Sometimes, finding brides along the way, they travelled to where the land was greener and set up new tents. Men looked longingly and courageously at the blue seas and wild rivers and set their strength to the building of great ships of cedar, eighty to one hundred feet long, weighing tons; or they made small boats of papyrus and sailed out to conquer an uncharted world.

Merchant caravans plied trade routes, crossing deserts, mountains and plains, carried their art and science to the lands they visited, and brought back to their own people the cultures of other lands. Kings and chieftains crossed swords, signed treaties, exchanged properties, and sent their daughters to each others countries, establishing stronger ties and territorial security through new family relationships.

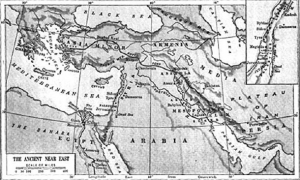

In the region of Western Asia called the Arab East lay the land of Canaan, that land of milk and honey where the Canaanites dwelt about five thousand years before Christ. Here they built the city of Jericho, and later the city of Damascus. It was in Canaan that the Jebbusites built Al-Salem, the “City of Peace,” which was later known as Jerusalem. Tyre and Sidon flourished along the coastal plain of The Lebanon, the “white mountain” of the Phoenicians.

Tyre, which the Phoenicians called Al-Sur, is a symbol of resistance to conquest and oppression. Nebachudnezzer besieged the city for thirteen years and Alexander the Great, unable to defeat it after seven months of constant battle, finally built a great dike over which his armies could pass in order to enter the city. Over the centuries an isthmus has formed where this dike once stood.[1]

Other Phoenician cities established centuries before the birth of Christ were Acco, Beirut, Smyrna, Arwad and Ugarit. In Ugarit, the present day Ras Shamra, the Phoenicians devised a cuneiform alphabet of twenty-nine letters. This invention, giving the world a simple form of communication which advanced the progress of commerce and promoted an international exchange of cultures, was perhaps the Phoenicians’ greatest contribution to man’s history. It was in Ugarit also, during the Assyro-Babylonian civilization of the second millenium, B.C., that a ballad, believed by scholars to be “the oldest song in the world,” was first played on a Sumerian lyre, establishing the tonal pattern for western music.[2]

The Canaanite Phoenicians, particularly those inhabitants of Aradus, Sidon, Tyre and Byblos were mariners. They literally sailed the world, charting the uncharted waters, discovering the Atlantic, circling the African continent about 500 B.C. They set course by the stars, developing and refining the sciences of astronormy and navigation.

The Phoenicians were merchants and traders, selling pottery, glass, woven products, paints, varnishes, cedar and wine. From Mediterranean waters they netted a shell fish, the murex, and extracted its essence to make their purple dyes.

During their centuries of travel, they colonized new cities and fathered descendants to populate them. (Legend says that Elissa, sister of the king of Tyre, angered by male domination during the 8th century B.C., crossed to Africa with a party of her supporters and founded Carthage – New City, and a new kingdom). Gaza, Tripoli, Joppa, Ascolon, and Ashdod, Tarsus, Hebron and Samaria were once Phoenician cities.

Following the European coastlines on the Mediterranean, the Phoenicians’ “Ships of Tarshish” named for an ore smelting colony in southern Spain, sailed into the harbors of Greece, Italy, Britain and France. The fishing boats which drift through the locks of Lisbon today, their red sails swooping back from bold broad prows are built in the unchanged style of the Phoenician craft of those ancient centuries. These small but sturdy boats sailed the Baltic, the Red Sea and the Aegean, and found their way to Hippo and Tangiers in Africa, and to the islands of Malta, Rhodes, Cyprus, Minorca and the Canaries.

For centuries the goods from all countries of the known world had floated on the waters of the Mediterranean, the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea and trade served as a bridge for the exchange of arts between east and west. The Phoenician King, Hiram of Tyre, sent cedars and mountain stone from The Lebanon to his friend, the Hebrew King, Solomon of Jerusalem, to build the Temple. In addition, he sent artisans skilled in the crafting of bronze and gold to create the magnificent designs for this wonder that Solomon was raising to the Lord. Solomon, in turn, sent Hiram twenty thousand kors of wheat and twenty thousand measures of pure oil each year for his household. The two kings enjoyed a close friendship, exchanging tests of wisdom and placing bets against each other.

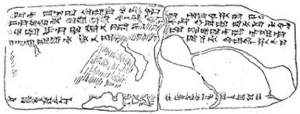

The Phoenicians travelled as far as Cornwall for tin. The record shows that Phoenicians travelled, in the years before the birth of Christ, even to the New World. A stone, marking the year 531 B.C., was discovered several years ago on the banks of the Paraiba River along the coast of Brazil, at a point about a hundred miles north of Rio De Janeiro.

Translated in 1967 by Cyrus Gordon, head of the Department of Mediterranean Studies at Brandeis University, the stone indicates that a band of Phoenicians found their way to the mouth of the river while seeking the rich iron reserves in the province of Minas Gerais.

“We are Sidonian Canaanites,” the tablet read, “from the city of the Merchant King. We were cast up on this distant island, a land of mountains. We sacrificed a youth to the celestial gods and goddesses in the nineteenth year of the mighty King Hiram and embarked from Ezion-Geber into the Red Sea. We voyaged with ten ships and were at sea together for two years around Africa. Then we were separated by the Hand of Baal and were no longer with our companions. So we have come here, twelve men and three women, into the ‘Island of Iron.'”[3]

Did these ancient Phoenicians reach the new world two thousand years before Columbus? Cyrus Gordon describes the “Hand of Baal” as a Semitic phrase meaning fate or divine will. A similar inscription has been found on Cyprus. Evidence, particularly in recent studies by Barry Fell of Harvard, points substantially to the existence of an active sea traffic between the old world and the new very early in the records of history.

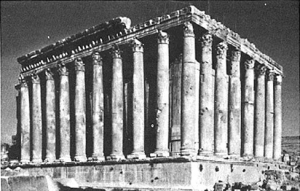

History shows us, however, that the exchange of culture and the inter-relationships of the world’s peoples have developed not only through commerce and trade, but through invasion, war and conquest as well. In the fourth century B.C., Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, Babylonia, Phoenicia, and Syria. A Macedonian, who ruled over Greece added new racial and cultural relationships to these lands. Following the Greek conquests came the Roman invasions and an Empire that flourished half way around the world. The Romans left temples behind in the Arab world, and the ruins at Baalbek in the Lebanon valley of the Bekaa serve today as a background for an annual international festival of music, dancing and theater. A French writer once said that “if the columns of Baalbek disappeared, there would be less beauty in the world, and less poetry in the skies of Lebanon.”[4] In Jordan, the Roman city unearthed at Jerash is among the most complete of the world’s archeological discoveries. Called “the town of the lazy generals,”[5] it was the Emperor Hadrian’s winter resort. Reliving the glory of Rome in Jerash one sees baths, fountains, statuary, a circular forum, three theaters, and the Temple of Artemis, the town’s patron goddess.

While the Romans made Jerash their own town, Petra, the rose-red city of the Nabatean Arabs, provides an archeological record of the peoples who conquered it. The Nabatean Arabs built inward into the mountain rock. The beautiful facades of their Temple, El Deir, and the Treasury, glowing pink in the desert sun, lie on the face of the mountains, the rooms themselves penetrating deep into the mountains. When the Romans conquered Petra, they built an Amphitheater which stands out bold and free, surrounded by the cliff side houses and tombs of the Arabs, the building styles of each culture so markedly different, yet each attesting to the creative genius of the men who built them.

Baalbeck — City of the Children of the Sun

The Acropolis of Baalbeck is the largest and best-preserved corpus of Roman architecture left to us. Its temples, dedicated to Jupiter, Venus and Bacchus, were built in the second and third centuries of the Christian era. The ruins present a majestic ensemble:

- Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Lebanon, Published by Neopublicite, Paris, undated. ↵

- Cleveland Plain Dealer -- March 6, 1974. ↵

- Fleming, Thomas. "Who Really Discovered America," Reader's Digest, March, 1973. ↵

- Brochure, National Council on Tourism, Republic of Lebanon, undated. ↵

- Brochure, Ministry of Tourism, Government of Jordan, 1969. ↵