Part V: The Immigration

Chapter 10: Early Visitors

THE NEW COLOSSUS

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land,

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon hand

Glows world wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest tossed to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”Emma Lazarus – 1883

History is not a chronological series of dates. It is, rather, a set of human experiences, some paralleling the general history of an era, others providing a counterpoint.

The Arabs, like all peoples, moved in and out of the accepted and routine patterns, becoming a part of their own history as well as part of the history of Europe and America. Coming out of an Arab dominated Spain, the navigators, geographers, and sailors upon whom Columbus depended to chart his course and man his ships, may have included Arabs who sailed to the new lands with the “Great Admiral of the Ocean Sea”[1] Some conjecture that the Pinzon brothers who piloted the Nina and the Pinta had Arabic heritage. It is recorded fact that Columbus, thinking he would meet the Grand Khan in his search for a new route to India, took along as his interpreter an Arab Jew who had converted to Christianity, Luis de Torres.

Arab navigators joined the Western adventurers in their discoveries and explorations. In addition to the Arab pilot who accompanied Vasco da Gama as he rounded Africa, Balboa gazed at the blue Pacific with an Arab Moor at his side. In 1528, a Moor, Estavan, arrived in what is now Florida and spent eleven years in the New World. In 1539, he served as a scout for Coronado in the Sothwest, being among the first to enter the present states of New Mexico and Arizona. He lived adventurously until his death in that year at the hands of Zuni Indians.

Early in the seventeenth century, Mohammed Ibn Ghanem al Navalishi came to America as an artilleryman and later served in Spain as Librarian for the Academy of the Artillery. He went to Tunisia in 1613 to become head of the artillery school in La Goulette.

In 1668, an adventuring Chaldean priest. Father Elias, or Ilyas El Mousili, from Mosul in northern Iraq, began a fifteen-year sojourn in the American Southwest among the Spanish settlements and missions, documenting the life and activities of the people of his time. He travelled north into the interior, was welcomed warmly, and received invitations to remain among the settlements. When he returned to his home in the Near East, his stories inspired dreams of the new world among his listeners.

Ten years before the visit of Father Elias, the English colony of Newport, Rhode Island, unique in its expression of religious freedom had already attracted Sephardic (Arab) Jews from Spain. A century later, rabbis from Jerusalem settled there. Among them was Hayim Isaac Karigal, who became a close friend of Ezra Stiles, later president of Yale.

Among the earliest of those who contributed to the building of America were Arabic speaking slaves, arriving in chains in 1733. These people were Muslims, identified by their refusal to eat pork, and by their language, which was interspersed with the names of Allah and Mohammed. While some were eventually freed and allowed to return to their homes, others spent their lifetimes on the plantations of Georgia and the Carolinas. One of the best known among these African slaves was Job Ben Solomon who was freed, spent some time in England among royalty and Arabic scholars, and then returned to Africa. There were other Muslim slaves in America. Prince Omar Ibn Said, a slave who died in 1859 at the age of eighty-nine, left a valuable diary of his philosophies and experiences. Paul Lahman Kibby spent forty years on a plantation, communicating to his American friends a philosophy of human relations that would banish ignorance and intolerance. Others lived and died in slavery, clinging to their traditions and religion, and adding their experience and heritage to the making of the new country.

The American Revolution was aided by supplies coming from Algeria, and along with the French, Hungarians, Prussians and Poles who were inspired by the ideals of the Revolution to volunteer their services, was a North African, Yusef Ben Ali, who, accompanied by a friend, joined the Americans. They served with General Thomas Sumter, who like Francis Marion and Andrew Pickens, had formed a guerilla band to fight an unorthodox kind of warfare in the forests and swamps of the South against Cornwallis. Coming from North Africa where this type of warfare was common, Yusef Ben Ali acquitted himself well. Indeed, in later years it was General Sumter’s support that won him the right to serve on a jury although he was “dark of skin.”

The American Revolution stirred a strong sense of admiration in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa, and in 1783, while other nations were still disputing America’s right to exist as a sovereign state, Morocco recognized the New Republic, the first nation in the world to do so. Later, as difficulties over trade arose between the United States and North Africa resulting in the Tripolitan War, Tunisia sent an Ambassador to the United States to try to reach agreements. He lived here a year, then returned to North Africa with a compromise that failed.

After the Barbary Wars, small numbers of Arabs from Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Algeria and Morocco again began to come into the United States.

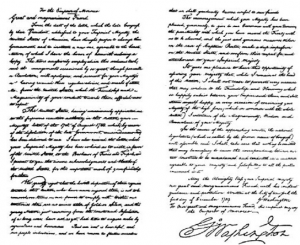

This is a facsimile of a letter in George Washington’s own handwriting. It is addressed to the ninth ruler of the Moroccan Alaouite Dynasty. The treaty mentioned is The Treaty of Peace and Friendship signed in 1787 which is considered to be the longest unbroken treaty relationship in United States history.

One of the most dramatic of visits was that of the special envoy of the Sultan Sayyid Said of Muscat and Zanzibar in 1840. Arriving on April 30th, after an eighty-seven day voyage, the Al-Sultana docked at New York, her crew of fifty-six Arab sailors causing a flurry of excitement among the three hundred thousand residents of that thriving metropolis.

The emissary, Ahmed Bin Na’Aman, was an Arab born in Basra, who had early developed a keen interest in the import-export trade. He had established an association with merchant ships from Salem, Massachusetts, and became known as “The Friend of the Salem Merchants.” A portrait of Bin Na’Aman, elegant in gold brocaded coat and silk turban, painted by Edward Mooney in 1840, hangs in the Peabody Museum of Salem, while another was displayed in the offices of the Art Commission of New York City.

The Al-Sultana carried ivory, Persian rugs, spices, coffee and dates, as well as lavish gifts for President Martin Van Buren. The visit of Bin Na’Aman and the Al-Sultana lasted nearly four months, in which time the “Friend of the Salem Merchants,”[2] and his officers were entertained by state and city dignitaries. They received resolutions passed by official bodies, were given tours of New York City, and saw sections which would, a few decades later, become colonies of Arabic speaking immigrants. Among Bin Na’Aman’s hosts was Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt in whose home he met Governor William Seward and Vice President Richard Johnson. The visit of Ahmed Bin Na’Aman to America was a happy one, and when he prepared to leave, the United States completely repaired the Al-Sultana, and presented Bin Na’Aman with gifts for his Sultan and himself.

Not all trips to America ended on such a happy note, however, and we find, among the early arrivals, experiences of disappointment, heartache and tragedy.

In 1849, a Melchite Bishop, Father Flavianus Kfoury, the Superior General of St. John’s Monastery in Khonchara, Lebanon, arrived in New York with a heart full of hope, and a companion, a Mr. Shedudy, who would serve as an interpreter to convey the good bishop’s appeal to the generous people of America. The civil insurrections of that decade between the Druze and the Christians had brought about the destruction of St. John’s Monastery, and Bishop Kfoury was looking for contributions to rebuild it.

Finding a good friend in the Bishop of New York, John Hughes, who armed him with two letters of introduction, and recommendations to the Irish Catholic parishes in the United States, the Lebanese Bishop set out on a two-year tour of the United States and Canada.

The Irish, themselves refugees in America because of failing potato crops in Ireland, met him with sympathy and helped him with what little money their parishes could spare. Ironically, the priest’s visit coincided with the growing nativist movement in America and, while Flavianus returned with some help for his church, he experienced moments of prejudice and animosity on his travels as well.

Strongly influenced by American tourists and Protestant missionaries, Antonio Bishall any, a young man from Selema in the Lebanon, served as a guide and cook on camping trips from Beirut to America and made lasting friendships with some of the American travellers. One in particular was the Reverend Charles Whitehead who later became his biographer.

In 1854, Antonio set out from Beirut to find his American friend. Antonio, dressed in a tassled fez and handsome Eastern clothing, and armed with addresses and an Arabic-English dictionary, walked the streets of New York, drinking in the sights and sounds. He had found at last the answer to his two-year dream to set foot upon the soil of America. He wanted neither fame nor a fortune, but only to study and to return to his people in order to teach them. Antonio’s desire to become a scholar and teacher was not fulfilled, unfortunately, but he did acquire the love of American friends. It was they who held his hand as he died from tuberculosis, two years after the date of his arrival in America.

The history of the American frontier is colored by an episode having Arab overtones. Following the Mexican wars and the acquisition of vast desert areas in the Southwest, Senator Jefferson Davis sought to discover a means of transportation that might prove superior to the wagon trains pulled by horses, mules and burros, who suffered a prodigious thirst crossing the long stretches of sand and salt. The mechanization of American transportation had not yet provided sufficient routes into the “Great American Desert,” and the conquest of the natural frontier still depended on the brawn, the cunning and the sheer primeval endurance of man and beast. What beast, then, might aid the American pioneer in building his future in the southwest? Why the Arabian camel, of course, said Mr. Davis, and other enterprising pioneers and politicians. That beast of all the beasts on earth could withstand days, even weeks, without food and water, and still plod, complaining and grudging to his destination. Two observers were sent to the Middle East to do one of the American government’s earliest feasibility studies. They concluded that camels could indeed be used to travel American deserts, and on May 14, 1856, the ship, Supply, arrived in Indianola, Texas, with its cargo of thirty-three hand-picked camels, and two Turks and three Arabs to handle them. The following year, forty-four more camels arrived, and it was not until the 1870’s, when the intercontinental railway linked the East to the Far West, that the work of the camel transportation corps was finished.

With the Near Easterners who accompanied the camel fleet to the south-west of America was a native of the Lebanon Mountains, Philip Tedro, who was also known as Hadji Ali. When some of the others returned home after their term of service, Hadji Ali and his brother remained in America to spend the rest of their lives in the booming West.

Hadji not only cared for the camels, but, becoming infected with gold fever, also prospected in the territories, tracking down the elusive gold where rumor and chance would take him. During those roaring, brawling, adventuresome years of the late nineteenth century, Hadji, who was affectionately known as “Hi Jolly,” served in the Arizona territory as a scout for the United States government.

He lived forty-six years in America’s southwest, comfortable with the new desert and the old familiar camels. He died in the desert in December of 1902, his arms flung around a dead camel. A camel tops the pyramid memorial marking his last resting place. He is eulogized as a faithful aide to the United States Government. By the time Hadji’s brother died five years later, in 1907, the heaviest of the waves of immigration were bringing thousands of his landsmen to America’s streets of gold.

- Letter from Isabella and Ferdinand. Washington Irving, Life of Columbus, Published by J. B. Miller and Co., New York, N.Y., 1895. p. 184. ↵

- Younis, Dr. Adele L. Thesis. "The Coming of theArabic Speaking People to the United States." Ph.D. Dissertation, Boston University. Graduate School of History, 1961. ↵