Part VI: Settlements and Settlers

Chapter 16: The Arab-American Parishes in Cleveland

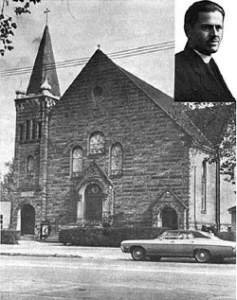

St. Elias Melkite Byzantine Catholic Church

The religious descendency of St. Elias Melkite Byzantine stems from conversion to Christianity by Jesus Christ and the Apostles. The origin of this Eastern rite Catholic sect dates back to the Church of Antioch.

Known in the dioceses of Jerusalem, Amman and Galilee as the Greek Catholiques, the Melkites trace their name to the Ecumenical Council of Calcedon in A.D. 451. Derided by the main Antiochian body they were identified with the “Melko” or emperor. Following the Emperor, they were the only Christians in the Middle East who upheld the doctrine of two natures in Christ.

The Melkite form of church government is identical with the autocephalous Orthodox Church, its bishops being elected by the Holy Synod which meets annually. This Synod compares to the Roman Curia and the College of Cardinals of the Latin Church. However, until the establishment of the Melkite Apostolic Exarchate of the United States in 1966, all Melkite parishes were under the jurisdiction of the local Latin rite Bishop. The Melkite rite is in communion with Rome. The Patriarch is the elected leader of the church. His full title is Patriarch of Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem and All the East. When elected, he requests the Pope of Rome to receive him into communion. In Lebanon, offices of the Permanent Synod are in Ain-Traz. In America, the diocesan offices for the United States are in Boston.

The Melkites in America, like members of other eastern rites, had for years, until the Second Vatican Council, endured attempts, within and outside the rite, to introduce Latinization into their liturgy. The decree of the Second Vatican Council that “All members of the Eastern Churches should know and preserve their legitimate liturgical rite and their established way of life” restored for many Melkite churches the earlier practices of the church. “First Holy Communion” and Funeral Masses have been abolished in numbers of churches. The three “Sacraments in Initiation,” Baptism, Confirmation and Holy Eucharist are administered by the priest to the infant in the same ceremony. While it was normal procedure in the Middle East to ordain married men into the priesthood, this practice is still prohibited in North America, as is the granting of divorce with permission to remarry.

The North American diocese now includes 26 parishes, seven missions, and four monasteries, with 20,000 members in organized parishes, and another 50,000 who do not live near a Melkite church. The first American Melkite parish was that of St. Joseph in Lawrence, Massachusetts which was founded in 1896. Five years later, in December of 1901, the Reverend Basil Marsha of Zahle, Lebanon, visited Cleveland and encouraged a number of the early Cleveland families to organize a Melkite parish in Cleveland.

The first Melkite Byzantine Liturgy in Cleveland was celebrated by Father Marsha on Christmas Day in the Chapel of St. Joseph’s Church on Woodland Avenue and East 23rd Street. This small group of Melkites continued to attend Mass celebrated by Father Marsha at St. Joseph’s until 1903 when a chapel at St. John’s Cathedral was made available to them. In 1903, they formed the St. George Society with the purpose of founding a parish of their own. Salim Caraboolad was elected its first president. In 1906, Joseph Jalylatie offered the use of a building at 2231 East 9th Street, which was converted into a church, and Bishop Ignatius Horstmann named Father Marsha the pastor of this Melkite community. This church was the first Melkite church west of New York and the third to be established in America. For a number of years it served the entire Lebanese-Syrian community, until each rite could establish churches of their own. As Father Marsha visited cities throughout the United States and Canada, Father Abraham Istaphan of Jennin, Syria, cared for the needs of the Cleveland parish. Plans continued for the purchase of a suitable church building and a number of families pooled their resources to bring to reality their hopes for an established church. The names of some of these founding families were: Abdou, Abraham, Aftoora, Anter, Caraboolad, Jaber, Jalylatie, George, Hashem, Karam, Kassouf, Macron, Maloof, Mansour, Nasrallah, Nyme, Otto, Tuma, Zarzour, Zegiob and Zlaket.

Two houses on Webster Avenue, at 1225 and 1227, were purchased on November 5, 1907, and remodeled into a church and a priests’ residence. Bishop John Farrelly dedicated the church in April of 1908. In the earlier years, the parish was known as the “Church of the Syrian Catholics” and was at times called “The Church of the Savior for the Syrian Catholics.” When the parishioners worshipped at the little building on East 9th Street, they called their church the “Church of St. Basil for the Syrian Catholics.”

Since many of these parishioners were originally from the Lebanese towns of Zahle and Khirbet Kanafar where the churches were dedicated to St. Ellas, the Prophet, it was decided to call the new church on Webster St. Elias Church, the name it has borne since 1908.

The first wedding in St. Elias on Webster was that of Saide Moshe Anter and Sa’aman (Sam) Heikell Macron in May of 1908. The first child to be baptized in the new church was Fuad Elias Boutros Nyme.

Upon the return of Father Marsha to his homeland in 1921, Bishop Joseph Schrembs of the Diocese of Cleveland appointed Rev. Malatios Mufleh pastor, a post he held until 1955, except for a one-year temporary assignment in Connecticut. Father Mufleh was convivial and outgoing, a good mixer who enjoyed a one-to-one relationship with his parishioners. He had a voice that rang pure and clear in the chanting of the liturgy in the little white church on Webster Avenue, a hand that was quick to cuff a restless schoolboy, or pull the curl of a dark-eyed, shy, little girl. A cigar was always clamped firmly in a mouth nearly hidden by a heavy black beard, which he refused to shave for years, much to the fury of some of his westernized parishioners. In the difficult years of transition with the church still accountable to the Latin Diocese, and parishioners demanding western innovations. Father Mufleh led the parish with a spirit of compromise, good humor and patience. He encouraged students in the Catholic high schools to conduct Catechism classes for young first communicants, nonchalantly accepting the preparation for the ceremony. He alone recognized that this was really a Second Communion, having, himself performed the first when he baptized these children. “Well, it’s all right,” he would reason, “their mothers want them to wear a white dress and veil and new white suits — they want to have something special here in the church, so what harm.” On confirmations he was equally amenable. “Well, if this child was confirmed at baptism, can it harm him to renew this dedication to the Holy Ghost? And is it not better to include him with all his American classmates when the bishop slaps their faces?”

In the earliest years of his pastorate, he encouraged the formation of clubs and organizations, one of the first being the St. Elias Ladies’ Guild in 1923. This group was a re-organization of one which had been started in 1915. A bazaar held in 1924 netted over $2,200.00, no mean sum for a small group of beginners in club work. Father Mufleh early recognized the effectiveness of a committed women’s organization and as the group broadened their activities, he encouraged them to continue in community and civic involvement. One of the highlights of their long record was the participation as a unit in the International Eucharistic Congress which was held in Cleveland in 1935. Asked to attend the nationality procession in native dress, the women decided that gowns representative of their early Christian rite would be most suitable. One of their members, Jennie Bowab Haddad, designed a long “thob” reminiscent of that worn by Mary the mother of Jesus, whom these women claimed as a daughter of Syria. The gown was of white silk crepe, its long wide sleeves lined with a deep cuff of blue and its flowing fullness girdled with a gold silk cord. A long veil, a mantille, of white chiffon completed the costume.

On the day of the procession, more than a hundred women — mothers with their teenage and married daughters, and old grandmothers taking slow and painful steps, marched in procession at the Cleveland Stadium, thousands of eyes upon their Holy Land dress.

The years of the Depression brought progress for the parish nearly to a standstill. Parishioners were forced to dedicate their energies toward economic survival for themselves and their families.

In those years Father Mufleh often strained the patience of some of his more affluent parishioners to the breaking point. Many a grocer or confectioner resorted to a string of profanities following the good priest’s visit to the store. “Ah ha,” Father would exclaim, shaking open a brown grocery bag, and sauntering around the store, “what beautiful oranges,” and into the bag he would drop a half dozen hand-picked oranges. A few firm, rosy apples would follow, and a can of coffee or a box of tea.

A visit to the ice cream parlor or confectionery resulted in a few Hershey bars and a pack of cigarettes finding their way into the brown bag.

While the grocers were having a hard time making ends meet, there were others in the Webster Avenue, Woodland and Central neighborhoods who had already sunk into the depths of poverty and despair.

For Father Mufleh the solution for balancing the economy was clear and simple. The grocers had a little extra — well, he would take some for those who had none at all. This way he could join the giver with the recipient in an anonymous act of charity in which all would benefit. Best of all, the cloak of secrecy preserved the undamaged dignity of the poor. If others wanted to think the priest was greedy, well, so be it — he was the priest. He blew his smoke rings and smiled.

As the parish outgrew the small church on Webster, a search was begun for a larger building and more parking space. In 1937, the South Presbyterian Church on Scranton Road and Prame Avenue was purchased for $20,000. The building was remodeled to suit the special needs of the Eastern rite and was dedicated by Bishop Joseph Schrembs of the Cleveland Diocese in 1938.

Added to the names of the earliest founders were names of families who worked to further the progress of the church on Scranton. Some of these were: Abood, Bader, Bird, Boukhair, Bou-Sliman, Elias, Essie, George, Haddad, Hakaim, Hallal, Hankish, Hanna, Hatton, Heikell, Holloway, Jacobs, Joseph, Kaim, Khoury, Kotoch, Morad, Nasser, Obde, Owen, Rassie, Razek, Rizk, Ryai, Sabath, Salim, Shaker, Tackla, Unis, Zambie and Zkaib.

The president of the Church Committee at that time was Dr. H. B. Khuri. During these years, a Junior Guild had been organized to involve the young people in church work. A Sodality for the younger matrons was named “Our Lady of Mt. Carmel” Sodality to commemorate the mountain of Elias, the Prophet.

By 1952, the responsibilities of the parish had increased enough to warrant the appointment of an assistant to Father Mufleh. Rev. Ignatius Ghattas, a native of Nazareth, Palestine, arrived in December to take up his duties at St. Elias.

In January of 1953, Father Mufleh was elevated to the rank of Archmandrite. One of the first responsibilities of the new assistant was to organize a Holy Name Society and to begin language and cultural classes for the parish children. A parish newspaper was also developed. A choir was trained which became noted for the excellence of its performances.

The choir often sang in other cities. Much of its music was recorded and sold well.

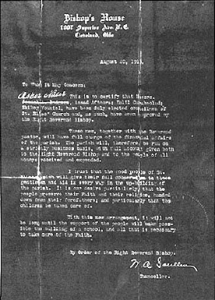

When the burdens of age and illness became too heavy for the pastor, Archbishop Edward F. Hoban named Rev. Ghattas “vicarius Adjutor” with full responsibility for the administration of the parish.

Under the guidance of Msgr. Ghattas, the parish continued to grow and plans were initiated in 1961 for the building of a new church. Funds were raised by solicitations, pledges and through such group efforts as bazaars, dances, teen and young peoples’ activities, banquets and anniversary dinners.

In 1964, the new St. Elias Church on Memphis Road, one of the finest examples of Byzantine architecture in the United States, was dedicated.

Today this church serves about 600 families, a number of them non-Arabs who have been attracted to the church by the cultural and educational programs developed by the pastor.

St. Maron’s Maronite Catholic Church

Ascribed to St. James the Less, Bishop of Jerusalem, the Maronite Rite is one of the oldest in the Church. Its liturgy is recited in Syro-Chaldiac or Aramaic, which was the language of Christ.

The Maronites are followers of a saintly hermit, Maron, (Mar Maroon) who lived in Antioch in the fifth century, but later took his followers from the Syrian Valley of the Orontes River into the Lebanon, the mountainous range of Greater Syria. Here the sect grew until it became the largest Christian community in Lebanon.

While the Maronites have been in communion with Rome since the 12th century, they are still governed autonomously by the Patriarch of Antioch, whose offices are in Lebanon.

The Maronite Rite is the only one of the Catholic Eastern Rites which does not belong to a Byzantine branch, its liturgy celebrating the Eucharist in expectation of the coming of the Lord, rather than as in the Byzantine liturgy, the risen Christ in His Glory.

The Maronite liturgy therefore, emphasizes the necessity of purification before the second coming of Christ, reciting after the Words of Consecration, “Do this in memory of Me . . . until I come again.”

The Canons of the Mass share their heritage with the Chaldean Rite, the Syrian Catholic Rite, the Old Syrian Rite, the Malabar Rite and the Malankar Rite of India.

Some of the liturgy has absorbed innovations from the Roman Church, notably marking changes during the Crusades, and following the printing of the Maronite Missal in Rome in 1592 and 1716, and the convening of the Lebanese Maronite Synod of 1736.

The Maronite Rite has spread to Cyprus, Egypt, Palestine, Iraq and Rhodes, and has emigrated from the east throughout North and South Africa, Australia, Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America and Europe. In the United States, the status of Exarchate has been elevated to that of a Diocese which consists of 45 parishes, and two institutions. Fifty-eight priests and twelve seminarians serve parishes in all 50 states. The Diocesan Seminary is located in Washington, D.C., and the See is in Detroit, Michigan.

Maronites were among the first of the early immigrants coming to Cleveland before the turn of the century. Some Cleveland Maronite families were instrumental in founding St. Elias Church. They attended not only St. Elias Church, but also St. Joseph’s and St. Anthony’s.

By 1914, there were at least a hundred families of the rite living in Cleveland. It was these people who formed the St. John Maron Society to collect funds and establish a parish of their own.

They acquired an old red brick residence on East 21st, furnishing the lower story as a chapel and designating the upper floor for a rectory. In 1915, Bishop John P. Farrelly blessed this building and the parish of St. Maron became a reality in Cleveland.

This site served the growing number of families until 1939 when it could no longer accommodate the increased population of the parish. The Italian-American church of St. Anthony on Carnegie Avenue was purchased, when that parish merged with St. Bridget.

The Maronite church in the former St. Anthony’s building at 1245 Carnegie was dedicated in 1940.

The first pastor of the Maronite parish was the Rev. Peter Chelala who served from 1915 to 1921 until he returned to Lebanon because of failing health.

St. Maron’s was then served in turn by Msgr. Louis Zouain, the Rev. Anthony Yezbek and the Rt. Rev. Msgr. N. S. Beggianni. In 1927, Archbishop Joseph Schrembs invited Father Joseph Komaid to become pastor of the parish, a responsibility which he held for twenty-five years.

Father Komaid was cast in the mold of the classic “pauvre abbe” of the flock. His church and its people were foremost in his priorities and he guided the parish through the early years of tribulation and trial with a gentle firmness and quiet strength that led a semi-educated community into the modern day participation in parish life.

His black cassocked slight figure became a familiar one as he walked from home to home in his parish around East 21st Street, or shopped for his meager needs in the grocery stores on Central, Woodland or Cedar Avenues.

His life was simple and uncluttered, centering around the small sparse study above the little chapel, from where he conducted the business of the parish.

The old-country priest was a realist however, and his quizzical penetrating gaze above his spectacles put all that he saw into a proper perspective. His life was one of celebrating the Mass, and taking care of the spiritual needs of the parish. The work of the parish leaders was to give support and raise funds.

The most dramatic and significant occasion of Father Komaid’s life was the ending of it. Certainly, it was a fitting climax to a discipline of acceptance and submission which had dominated the years of his priesthood.

On June 19, 1952, his parishioners, members of other Arab-American parishes and community leaders had gathered at a testimonial banquet to honor the priest on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his ordination and the 25th of his pastorate at St. Maron. Following a number of long speeches by the usual assortment of dignitaries, the old priest was called upon to receive the honors that would climax the evening. Rising to the rostrum, the good father was silent for a moment, gazing out over the audience of several hundred who had come to honor him. He took a faltering step, stretched out his arms, and whispering the words of the ancient prophet, “Receive Thy Servant, Oh, Lord,” slipped quietly to the floor, dying. The cries of his parishioners were the last earthly sounds to reach his ears. Chor-Bishop Joseph C. Feghali came to Cleveland in 1951 to serve as assistant to Father Komaid. Upon the death of the old pastor, Father Feghali assumed the responsibilities of the parish, receiving over the years the titles of Very Reverend Monsignor, and then Chor-Bishop. Msgr. Feghali left Cleveland in 1977.

Among the approximately six hundred families are some whose names have been prominent in the parish activities from the earliest days of its history. Members of the Abood, Kallil, Nahra, Amor, Shaheen, Ezzie, Hanna, Tadrous, Ganim, Thomas, Asher, Oakar, Shibley, Naffah, Shalala, Nakhle, Rumya, Sadd, Ferris, Boger, Shaia, Nemer, Khoury, Hitti, Illius, Ellis, Saba, Sadie, Shiban, Said, Nader, Abraham, Albainy, Hillow, Harouny, Asseff, Bouhassin, Elias, George, Hassey, Ina, Jacobs, Joseph, Lewis, Louis, Maroon, Najjar, Peters, Zarzour and Zlaket families are among the Lebanese and Syrians who have actively participated in parish projects throughout the years.

Such names as Blackman, Burton, Cosentino, Corbett, Fedor, Holt, McKee, Martovitz, Paradise, Root, Tucker and Weiss, evidence the increase of mixed marriages, as well as the conversion to the church of persons of non-eastern heritage. Parish organizations include: The Council of St. Maron’s, The Immaculate Conception Sodality, the Sacred Heart of Mary Guild, the Holy Name Society, the Maronite Adult Club, Maronteen Club and Altar Boys. The present pastor is Father Elias Abbi-Sarkis.

St. George Antiochian Orthodox Church

The Cleveland Grays, organized in 1837 as a parade and military unit were associated with early Cleveland history long before the immigration into Cleveland of the Syrian-Lebanese families who founded St. George Antiochian Orthodox Church.

In 1893, during the peak years of Arab immigration to Cleveland, the Grays built their Armory at Bolivar Road. It was an imposing stone and brick fortress, with turrets and towers reminiscent of Crusader castles built centuries before on the deserts and plains of the Middle East.

Here the Grays conducted their meetings, performed their drills, held band practice and shared convivial hours with fellow members in the club rooms of the Armory.

A haze of cigar smoke thickened the air on weekday evenings, as the voices of men at their sports echoed through the Billiards room.

The Armory was used for civic and cultural activities — dances, convention meetings, the Centennial celebrations of 1896. It was not yet a time when immigrants and the established “WASP” community were meeting generally on intimate social levels, yet someone in that early Arab community and someone among the “establishment” must have enjoyed the kind of friendship that linked the history of the Cleveland Grays with that of the Orthodox Syrian Lebanese community of Cleveland.

The names of those two individuals, the “American,” and the transplanted Syrian, who negotiated the arrangement are lost in history, but some time in those early years of Grays Armory and the Orthodox community the Billiards Room at the Armory was witness to another kind of gathering.

The haze of cigar smoke was replaced by the sweet pungency of incense, rising from an acolyte’s censor, and the happy sportsman voices, deferred on Sundays to the intonations of the cantor as the Liturgy of the Eastern rite Antiochian church was sung for the faithful.

With no church or priest of their own, the faithful Orthodox were thus able to retain their identity and preserve the rite of the mother church in Syria. Grays Armory as well as St. Elias Melchite Catholic Church, was always included with happy remembrance, in the recounting of the church history of Cleveland’s Orthodox community.

After years of Sunday services in these and other locations, members of the congregation in 1926, met with Archbisop Victor Abou Assaly, North America’s first Metropolitan, in the home of Abraham Sahley on West 14th Street. They had waited more than thirty years. Finally the moment of decision had arrived. They would have a church of their own in Cleveland. Two homes on West 14th and Buhrer Avenue were purchased with the intention of using their site as a future church building, but eventually this plan was changed.

In 1927, Father Elias M. Meena, who had come from Vicksburg, Mississippi to visit relatives, was invited by members of the early congregation to become their pastor and make Cleveland his home. Again a meeting was held in the home of Abraham Sahley. This resulted in the appointment of Father Meena as first pastor of St. George Church by the Metropolitan, Archbishop Assaly.

This Orthodox congregation and its foresighted new pastor from the beginning seemed to be early advocates of an ecumenism not experienced until years later by other congregations.

The Seventh Day Adventists had a church on West 14th and Buhrer and the new Pastor and his congregation made arrangements with Adventist Church leaders to hold Divine Liturgy on Sundays in the Adventist church.

Some months later, a small group of co-signers purchased a church at West 14th and Starkweather for $38,000. These early founders, Habeeb George, George Gantose, Joseph Hanna, George Hanna, Abraham Sahley and Nasef Salim presented the key to the “new” church to Father Meena in July of 1928.

The congregation of this new Orthodox church in Cleveland immediately threw their energies into the formation of a Ladies Society, a Choir, a Band, and a church council. They raised funds with card socials, bazaars, picnics, and Thanksgiving dinners. The band, a favorite project of the new pastor, became well known and performed, not only at church events but also at many civic functions.

Within five years, funds had been accumulated to decorate and ornament the church. Sadly, immediately after the celebration to mark this milestone on May of 1933, the most spectacular fire on Cleveland’s west side to that date totally destroyed the newly ornamented church, leaving only the skeletal four walls standing.

The initial grief was followed by renewed vigor and enthusiasm, and the same parishioners who had just seen their money and labor go up in smoke, threw themselves into the task of rebuilding.

Another mortgage was assumed. Finally, in 1935, the newly constructed church was consecrated by Archmandrite Antony Bashir.

In less than ten years, on November 14, 1943, at a testimonial dinner at the old Carter Hotel, the mortgage was burned. Father Elias Meena moved to California in 1951 after a service of twenty-five years to St. George.

It was a parting frought with emotion. This priest who had worked with hammer and saw, side by side with Kareem Courey, the carpenter, in the rebuilding after the fire, had endeared himself to his parishioners. His leadership qualities and driving force had brought the church through disaster and depression to enduring stability.

Other pastors to serve this parish in the years following Father Meena’s pastorate were Fathers George Simon, Paul Moses, Elias Nader, Thomas Skaff, Philip Saliba, Nicholas Van Such and Gibran Ramlaoui.

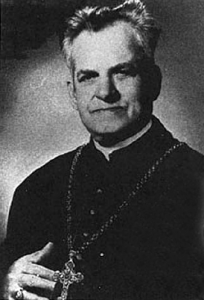

Philip Saliba was ordained in Cleveland in 1959, in St. George, to which he had come as an arch deacon. He became pastor soon after ordination. He was elevated to Archbishop seven years later and is at the present time the highest ranking Orthodox religious leader in the Northern Hemisphere, Metropolitan of North America and Canada. He holds jurisdiction over Australia as well.

Rev. Gibran Ramlaoui was transferred from Cleveland to become Bishop of Australia.

The first Sunday School at St. George was organized in 1940, and its first, superintendent was Lillian Sahley, (Mrs. Farris) the daughter of Abraham and Deebe Sahley, early founders. Following her death, her husband, Farris, provided an endowment toward construction of a Sunday School building in her memory.

The expansion program initiated in 1963 included a new Educational and Cultural center, of which the Sunday School was a part.

A third mortgage was burned in 1968 on the date of the 40th anniversary of St. George Church — that time for the Educational and Cultural Center, the first of its kind in the North American Archdiocese.

The ornamentation in the interior of the church is Byzantine in character, although two wall paintings are typically Latin. These depict the Last Supper and the Resurrection. Of them. Father James C. Meena, the present pastor and son of the first pastor, says: “There is no explanation for them except that my father always liked the originals and decided these would do very well for our interior. He had a sense of ecumenism before his time, and these are among the few, if any other, Roman and western religious paintings in an Orthodox Church in America.”

The icon wall, the “iconostasis” separating the sanctuary main part of the church, stands from 1935 when the newly reconstructed church was opened.

Its builder, David Deeb, an artisan born in Damascus, painstakingly carved by hand the heavy wooden wall, its richly cut pillars and recessed niches framing the brilliant glowing colors and exquisite gold leaf of the icons.

David Deeb at that time was sixty years old, and this was his gift of labor for the new church. In 1954, at the age of seventy-nine, this same artisan, his hands twisted and trembling with arthritis again set himself a labor of love for his church. “The church must have a Bishops’ Throne,” he said, noting the tradition of this fixture for the interior of an Orthodox church. “I will build this throne, my last work, as a legacy to my church, and I will do it myself.” David Deeb then proceeded, slowly and painfully, to design and then build, alone and unaided, a fourteen foot throne. Cupolaedand canopied, it was carved of dark walnut. Into the magnificent gleaming wood Mr. Deeb carefully set inlaid ebony, rosewood and ivory in an ornamentation of religious symbols. While it did indeed remain his last major work, Mr. Deeb lived an additional fifteen years, his eyes resting with satisfaction each Sunday upon that throne at the right of the icon wall. The tabernacle in the church was the core around which his social, cultural and religious life had revolved for nearly half a century.

Kareem Courey, the carpenter, built the first wooden casket which was carried in procession each Good Friday to commemorate the crucifixion and death of Christ.

“There have been others since, and now they have an aluminum one,” said his son, Naissef Courey, “But one of my father’s greatest joys is that the coffin he built was the first to be carried around the church and into West 14th Street during the Good Friday procession.”

Of the five hundred families in St. George Parish today, many bear the names of those early immigrants associated with the church from its early history. There are a number of George families, among them the children and grandchildren of Habeeb George, one of the co-signers and of his brother, Shaheen George.

Also included among the present parishioners are the families of other co-founders — the children of Abraham and Deebe Sahley; the Gantose families, the Hannas, the Salims. Other families carry the names of Abraham, Abdutlah, Assad, Aboid, Ameen, Betor, Bourjailly, Courey, Darwish, Deeb, Esber, Easa, Elias, Farage, Farris, Farah, Fadil, Haddad, Houry, Haikim, Harants, Khoury, Kaleal, Kaleel, Karam, Karim, Kerby, Isaacs, Jacob, Joseph, Lakis, Mady, Nader, Namy, Rahal, Sadallah, Sadie, Shiban, Simon, Shiekh, Saba, Shahady, Sarkis, Saah, Shawan, Shakour, Shaker, Thomas, Yunis and Zeen.

With changing social patterns and increasing mixed marriages, many families now carry names with European roots, as well as names identifying Mediterranean cultures other than the Arabic, such as Greek, and Italian. Such names as Daddoukh and Yahyah were long associated with St. George Antiochian Orthodox Church. Says one parishioner: “Mr. Abbas Daddoukh and Dr. Yahyah are Druze by religion, but the Druze had no temple or meeting place for a long time, and many of the Druze families participated in our services, and joined our organizations.”

Pastors of St. George have throughout the years encouraged group participation in religious and cultural activities and a number of organizations meeting at the church are involved in national Orthodox activities.

SOYO, (Syrian Orthodox Youth Organization) has a strong chapter in Cleveland. Many of the St. George young people are involved on the state and national level. Other groups include the St. George Choir, St. George Church School Guild, St. George Ladies Society, St. George Teen Club and St. George Altar Boys.

Social and cultural groups include the United Aramoon Society and the Kouba Club, which are named for the towns in Lebanon from which their early founders immigrated.

The present pastor of St. George Church is the Very Rev. James C. Meena, the second son of the church’s founding pastor. Father Elias Meena.

There was once another James Meena, the first son of Father Elias Meena.

An old program book for a St. George function contains a memorial which reads: 1st Lieutenant James Meena, born 1916, killed in action November 11, 1944. That James Meena was a graduate of the Cleveland Institute of Music and already singing in opera and studying for the priesthood when he was called into service during World War II where he lost his life. The baptismal name of the present Father Meena was Carnal. After serving with the army in North Africa and Italy, he came home to study for the priesthood in his brother’s place. Upon ordination, he assumed his brother’s name, and has been known since that date in 1950 as James C. Meena. His parishioners call him Father James. Father Meena at first served the North American Diocese in teaching capacities, and was several times director of Religious Education and Sacred Music for the American Archdiocese.

Before assuming the pastorate of St. George in 1970, Father Meena served in St. Nicholas Cathedral in Los Angeles, and St. George Church in Pittsburgh, and was once assigned to travel as a delegate in the Middle East to the Holy Synod in Damascus and Beirut.

While in St. George in Pittsburgh, he hosted a radio-TV show for two years on WIIC, and served on the Mayor’s Advisory Committee on Human Relations.

He is a graduate of Baldwin Wallace College in Berea, and has studied Musicology, Arabic, Music Composition and Theory at the University of Southern California, UCLA, and Duquesne. Father Meena is the author of three Hymnals for the Divine Liturgy, and has translated the Tschaikowsky Liturgy from Slavonic to English.

He is married to the former Ruth Farris and is the father of a daughter and three sons.

Under his direction, the church has expanded its activities into areas of community involvement, particularly in the Tremont poverty and welfare programs, and has offered its meeting rooms and facilities to programs developed by other organizations within the Greater Cleveland area.

St. Mark Coptic Orthodox Church

The word “Copts” is derived from the Greek word “Aegyptus” meaning Egypt. The Copts are the descentants of the ancient Egyptians who were converted to Christianity by St. Mark (a disciple of Jesus Christ) who was of African origin. St. Mark was the author of the earliest Gospel. In the year 42 A.D., he came to Egypt bringing the Christian faith to that old civilization. He preached in Alexandria where he founded the Church of Egypt. In 451, the Coptic church broke away from Rome because of some disputes about the nature of Christ.

The present head of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Egypt is H. H. Pope Shenouda III, of Alexandria and patriarch of the see of St. Mark. The church has some 1.5 million members in Egypt and 3.5 million in Ethiopia.

Pope Shenouda III appointed a six member committee to represent the Coptic Church in America. Two of these members live in Cleveland. One is Mr. Ahdy G. Mansour, Executive Director of the Lake County Society for Crippled Children and Adults, and the other is Father Mikhail E. Mikhail, Pastor of St. Mark Coptic Orthodox Church in Parma.

Father Mikhail came to America with his wife, Seham, in 1975 when he was appointed Pastor of St. Mark’s Church. The church was officially established on February 25, 1971 even though services were held every two months. Previous to that time, services were held every two months in the private residence for 10 Coptic families since 1968 by a visiting priest from Toronto, Canada.

Presently, St. Mark’s Coptic Church serves all Coptic faith living in Ohio, most of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Minnesota. The church has approximately 400 members in Cleveland, an additional 200 in other parts of Ohio, 120 in Pennsylvania, and 200 in Minnesota.