Part III: Arab Contributions to the West

Chapter 7: Contributions in the Sciences and Mathematics

The years between the seventh and thirteenth centuries are the period in history when culture and learning flourished in North Africa, throughout Asia, on the western coastal area of Europe, (Spain, Portugal, Italy and France), and on the island strongholds along the western and southeastern coasts of Europe (Gibralter, Rhodes, Sicily, Crete, and Cyprus).[1] When we set aside the vagaries of politics, intrigue, mistrust and suspicion which have plagued man’s history, we find that the Arab World continued to spin out the thread of earliest recorded civilization, enhance and develop the arts and sciences, and preserve the libraries of the early centuries of Greek, Roman and Byzantine culture. Indeed, during the Dark Ages of Europe, much learning was preserved for the world through the Arab libraries in the universities of Morocco, Nigeria, Egypt (Fez, Timbuktu, and Al-Azhar). From this period of Arab influence, new words such as orange, sugar, coffee, sofa, satin, and algebra filtered into the language of Europe and eventually into our own. New discoveries were made in the sciences and arts which improved the lives and condition of man.

Mathematics

In mathematics, the Arab cipher, or zero, made workable the solution of complicated mathematical problems. The Arab numeral, an improvement on the original Hindu invention, and the Arab decimal system made simpler and more flexible the course of science.[2]

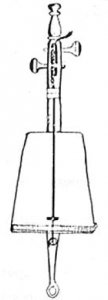

The Arabs invented and developed Algebra and made revolutionary strides in trigonometry. Al-Khwarizmi, credited with the invention of Algebra, was inspired by the need to find a more accurate and comprehensive method to assure the precise divisions of land so that the Koran could be specifically obeyed in the laws of inheritance. The Astrolabe, combining the use of mathematics, geography and astronomy was also devised with religion in view, and was used to chart exactly the time of sunrise and sunset, to determine the time for fasting during the month of Ramadan. The writings of Leonardo da Vinci, Leonardo Fibonacci of Pisa and Master Jacob of Florence show the Arab influence on mathematical studies in European universities.[3]

The reformation of the calendar, with a margin of error of only one day in five thousand years was also a contribution of the Arab intellect. Indeed, in our every day commerce, whether it is in yard goods, lumber, or ingots of gold and silver, we use the weights and measures by which the Arabs of the past conducted the business of their every day life.

Astronomy

Beside the improvement of the ancient Astrolabe, the Arab astronomers of the Middle Ages compiled astronomical charts and tables, in observatories such as those at Palmyra and Maragha. Gradually, they were able to deter-mine the length of a degree, to establish longitude and latitude, and to investigate the relative speeds of sound and light. Al-Biruni, considered one of the greatest scientists of all time discussed the possibility of the earth’s rotation on its own axis, a theory proven by Galileo six hundred years later. Arab astronomers such as Al Fezari, Al-Farghani, and Al-Zarqali added to the works of Ptolemy and the classic pioneers, in the development of the magnetic compass and the charting of the Zodiac.

At Maragha, in the thirteenth century, distinguished astronomers from many countries gathered to work. Christians and Jews were among them, and the Chinese who came took back to China Arab trigonometry for their own scientific experiments.[4]

Medicine

In the fields of medicine, the Arabs continued to improve on the healing arts of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Al-Razi, in the ninth century, a medical encyclopedist, was an authority on contagion. Of his many volumes of medical surveys perhaps the most famous is the Kitab al-Mansuri, which was used in Europe until the sixteenth century. Al-Razi was the first to diagnose small pox and measles, the first to associate these diseases and others with human contamination and contagion, the first to introduce such remedies as mercurial ointment, and the first to use animal gut for sutures.[5]

The great medical scholar known in the west as Avicenna was the Arab, Abu-Sina who was both a philospher and a scientist. He was the greatest writer of medicine in the Middle Ages and his Canon was required reading throughout Europe until the seventeenth century.[6] Avicenna did pioneer work in mental health, and was a forerunner of modern western psychotherapists. It was his belief that some illnesses were psychosomatic and he would sometimes lead a patient back to a recollection of an incident buried in the subconscious which caused the present ailment.

In the fourteenth century, when the Great Plague ravaged the world from India and Russia across Europe, Ibn-Khatib and Ibn-Khatima of Granada recognized that it was spread by contagion.[7] Ibn-Khatib’s most important medical work is called “On the Plague.” Al-Maglusi, in the book, Kitabu’l Maliki showed a rudimentary conception of the capillary system,[8] and an Arab from Syria, Ibn al Nafis, discovered the fundamental principles of pulmonary circulation.[9]

Camphor, cloves, myrrh, syrups, juleps, and rose water were stocked in Arab “sydaliyahs” (pharmacies) both in the East and in Europe centuries ago. Herbal medicine was widely practiced, and basil, oregano, thyme, fennel, anise, licorice, coriander, rosemary, nutmeg, and cinnamon found their way through Arab pharmacies to western tables.

Architecture

As in astronomy and mathematics, the great purpose in Islamic architecture was to glorify the Faith, and Muslim builders devoted their skills to the building of mosques and mausoleums. They took over the horseshoe arch from the Romans, developed it to their own unique style, and made it an example for the architecture of the West. The Great Mosque of Damascus, built in the early eighth century, was a beautiful demonstration of the use of the horseshoe arch, and the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, with its pointed arches, was the inspiration to medieval French, German and Italian architects in the building of the magnificent Cathedrals of Europe.

Cusped, trefoil and ogee arches provided the models for the Tudor arch such as those used in the cathedrals of Wells in England and Chartres in France.[10] The Muslim minaret, itself inspired by the Greek light-house, became the campanile in Europe, one of the most famous examples being seen in the San Marcus Square in Venice.[11]

Designs from the Islamic Mosques of Jerusalem, Mecca, Tripoli, Cairo, Damascus and Constantinople were borrowed in the building of ribbed vaults, and the construction of domes on a cube by the creation of transitional structural supports was incorporated into the cathedrals and palaces of eleventh and twelfth century Palermo.

To these great structures the Arabs applied magnificent coverings. Their styles were elegant and daring. Arabesque, caligraphy, explosions of color and pattern are to be seen today in such structures as the Lion Court of the Alhambra Palace in Granada, the Great Mosque of Cordoba, and in many of the great medieval religious and civic buildings of much of Europe.

While we are more familiar with the influence of Arab architecture in the Romance countries of Spain, Italy and France, we do not often remember that the Arab invasions reached into central and Eastern Europe as well, and here, particularly in Russia, are startling remnants of a once power-ful conquest. The brilliant blue tiled dome of the Mosque of Bibi Khanum, Timur’s (Tamerlane) favorite wife, catches the visitor’s eye as he turns a corner of the road in Samarkand. Here as well as in the complex of tombs called Shah-i-Zinda (The Living Prince), restoration is taking place and much of the old beauty is being returned to its former elegance.[12]

Navigation and Geography

The world’s earliest navigation and geography were developed by Canaanites who, probably simultaneously with the Egyptians, discovered the Atlantic Ocean. The medieval Arabs improved on ancient navigational practices by the development of the magnetic needle in about the ninth century.

One of the most brilliant geographers of the medieval world was Al-Idrisi, a twelfth century scientist living in Sicily. He was commissioned by the Norman King, Roger II, to compile a world atlas which contained seventy maps, some of the areas heretofore uncharted. Called Kitab al Rujari (Roger’s Book), Idrisi’s work was considered the best geography of its time.[13]

Then there was Ibn Battuta, who must have been the hardiest traveller of his time. He was not a professional geographer, but in his travels by horse, camel and sailing boat it is estimated that he must have covered seventy-five thousand miles. His wanderings, over a period of decades at a time, took him to Turkey, Bulgaria, Russia, Persia, and central Asia. He spent several years in India, and from there was appointed ambassador to the Emperor of China. Going from China he visited all of North Africa, and then went to many places in western Africa, stopping in Mali, Timbuctu and the Niger region.

Ibn Battuta’s book, Rihla (Journey), was filled with information on the politics, social conditions, and economics of the places he visited, as well as their geographical facts. Like Marco Polo, he faced incredulity, but eventually was proven a truth teller.[14]

However, it was a twenty-five year old Arab, captured by Italian pirates in 1520 who has received much attention from the West. He was Hassan al Wazzan, who became a protege of Pope Leo X. Leo persuaded the young man to become a Christian, gave him his own name, and later con-vinced him to write an account of his travels on the then almost unknown “black” continent. Hassan became Leo Africanus, and his book was translated into several European languages. For nearly two hundred years, Leo Africanus was read as the most authoratative source on Africa.[15] It will be remembered too that in the fifteenth century Vasco de Gama, exploring the east coast of Africa near Malindi, was guided by an Arab pilot who used maps never before known to Europeans. The pilot’s name was Ahmed ibn Majid.[16]

Horticulture

The Arabs loved the land, for in the earth and the water they saw the source of life and the greatest of God’s gifts. They were guided by the words attributed to the Prophet: “Whoever bringeth the dead land to life . . . for him is reward therein.”

They were pioneers in botany, and in the twelfth century an outstanding reference work, Al-Filahat by ibn-Al-Awam, described more than five hundred different plants and methods of grafting, soil conditioning and curing of diseased vines and trees.[17]

The Arab contributions to food production are legion. They were able to graft a single vine so that it would bear grapes in different colors, and their vineyards produced the future wine industries of Europe.[18] Peach, apricot and loquat trees were re-planted in southern Europe by Arab soldiers. The hardy olive was encouraged to grow in the sandy soil of Greece, Spain and Sicily to begin the olive and oil industries. From India they introduced the cultivation of sugar, and from Egypt they brought cotton to European markets. “May there always be coffee at your house,” was their expression wishing prosperity and the joy of hospitality for their friends. Coffee was “Qahwah.” that which gives strength, and derivatives of that name are used today in almost every country of the world. They also perfected the storage of soft fruits to be eaten fresh throughout the year.[19]

Arab horticulture gave the world the fragrant flowers and herbs from which perfumes were extracted. Their walled gardens were for the pleasure of the senses — a pine tree standing green and aromatic in the heart of a garden scented with jasmine; a fountain or artificial pool to delight the eye admidst lavender and laurel; a special rose garden blooming in riotous color, the roots injected with saffron to produce yellow, and indigo to produce blue flowers; vines and trees injected with perfumes in the autumn flooding the air with fragrance in the spring; a weeping willow dipping gracefully into the middle of a clear lake; arbours and pergolas constructed where streams of water could bubble through them, cooling the air and giving relief from the heat of the desert.

Mimosa and wild cherry lavished color against stone walls, and cypress grew tall, close, and straight, bordering alleyways to obliterate from view all that was not pleasing to the sight.

They were not quick to cut down barren trees. “Don’t do that,” one would say to the other, loudly, within earshot of the ailing tree.

“Why not? It is not bearing fruit.”

“Yes, but it might bear next year. Leave it, let us see,” and the tree, as though realizing it had been given a second chance, might bear an overabundance of fruit the following spring.

Bulb flowers were already in a highly hydridized, cultivated state when the Crusaders carried them home from Palestine to western Europe toward the end of the centuries of Arab power. Rice, sesame, melons and shallots, as well as dates, figs, orange, lemon, and other citrus fruits, pepper, ginger, and cloves were introduced into the European cuisine via the Crusades and the trade caravans of Eastern merchants.

The women of the west borrowed from the cosmetics first prepared by the Egyptians, Syrians and Phoenicians — lipsticks, nail polish, eye shadows, eye liners (kohl) perfumes and powders, hair dyes (henna), body lotions and oils, even wigs.

A symbol of the vanity of the medieval ladies of European courts, was the high peaked pointed cap with its trailing veil of silk. This fashion of Jerusalem was called the tontour, and noble ladies of both the East and the West vied with each other on the height of the tontour and the elegance of the fabrics used in the design of this face-framing millinery.

Much of our contemporary jewelry takes its inspiration from the adornments of the ancient and medieval Arabs, and the highly prized squash blossom design was once on the uniform button worn by Spanish conquistadors.

Other Sciences

In Arab engineering we can look to the water wheel, the cistern, irrigation, water wells at fixed levels, and the water clock.

In 860, the three sons of Musa ibn Shakir published the Book on Artifices which described a hundred technical constructions, and one of the earliest philosophers, al-Kindi, wrote on specific weight, tides, light reflection and optics.[20]

Al-Haytham, born in the tenth century, wrote a book on Optics, Kitab-al-Manazir. He explored optical illusions, the rainbow, and the camera obscura, which was the beginning of photographic instruments. He also made discoveries in atmospheric refractions — mirages and comets — studied the eclipse, and laid the foundation for the later development of the microscope and the telescope. Al-Haytham did not limit himself to one branch of the sciences, but, like many of the Arab scientists and thinkers, explored and made contributions in the fields of physics, anatomy, and mathematics. In Europe, he was known as Alhazen.[21]

The Crafts

Because the Arabs believed that the arts served the Faith, they raised small scale artistries to new levels of perfection. Glass making, ceramics, and textile weaving attested to their imagination and special skills.

They covered walls and objects with intricately detailed mosaics, tile, carving and painting. Syrian beakers and rock crystal were highly sought after in Renaissance Europe, and the Azulejos, the irredescent lustre pottery from the Moorish kilns in Valencia also enjoyed great popularity.

New glazing techniques were developed, and the brilliant blues took on many names. The Chinese called them Muhammedan blues, Dutch traders called them Chinese blue[22] — an interesting reflection of the cultural exchanges between countries and their artisans.

They were masters of silk weaving and the Arab cape worn by Sicily’s King Robert II on his coronation is one of the examples of this delicate art.[23] Cotton muslin. Damask linen and Shiraz wool became watchwords of quality in textiles in Europe.

Today, we speak of Morocco leather as of especially fine quality. The Moroccan tanners of the Middle Ages developed methods for tanning hides almost to the softness of silk and used vegetable dyes that retained color indefinitely. These leathers were used for book binding, and the gold tooling and colored panels of the Arab style are still being produced, particularly in Venice and Florence, to the present day.

From India the Arabs drew the art of crucible steel forging, developed the process, hardened the steel, polished it and decorated it by etching, and produced tempered, flexible Damascene swords. Other works in metal were intricately cut brass chandeliers, ewers, salvers, and jewel cases inlaid in gold and silver, and, of course, the beautifully decorated Astrolabe prized by the sea captains.

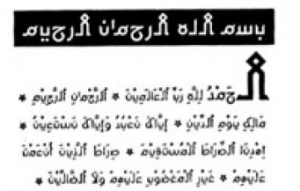

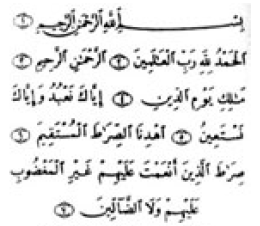

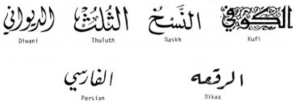

Language and Caligraphy

Because God spoke to Muhamed in Arabic, Arabs venerate their language, and calligraphy became yet another art form. It was the chief form of embellishment on all the mosques of the Arab world, and the religious and public buildings of Palermo, Corboda, Lisbon and Malaga are resplendent with it.

The language is rich and pliant, and poetry, literature, and drama have left their mark on both East and West.

Among the earliest publications of the Arabs were the translations into their own language of the Greek and Roman classics — the works of Aristotle, Plato, Hippocrates, Ptolemy, Dioscorides and Galen. They translated, too, the Old Testament, since their own religion was based in great part on it, and later, the New Testament for the inclusion of certain verses in the Koran.

It is believed by some that the poet Nizami’s twelfth century romance, Layla and Majnun, one of the most popular Persian love stories, may have been an inspiration for Romeo and Juliet.

Hayy ibn Yaqzan (Alive, Son of Awake) by the twelfth century philosopher, Ibn Tufail, considered by many to be the first real novel, was translated by Pocock into Latin in 1671 and by Simon Ockley into English in 1708. It bears close similarities to Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.[24]

The Thousand and One Nights and Omar Khayam’s Rubaiyat were among the best loved and most widely read of Islamic literature.

The fascination with Arabism, following the Hellenistic period of Louis XIV, is evident particularly in Shakespeare’s characterizations of the Moors, Othello and the Prince of Morocco, in Christopher Marlow’s Tamburlaine the Great, and George Peel’s The Battle of Alcazar.[25]

Besides influencing “belles lettres,” the Arabs developed a system of historiography called “isnad,” documenting all reliable sources and providing the modern historian with accurate and comprehensive materials. Foremost among these historiographers was Ibn Khaldun, of whose Book of Examples Arthur Toynbee writes: “Ibn Khaldun has conceived and formulated a philosophy of history which is undoubtedly the greatest work of its kind that has ever yet been created by any mind in any time.”[26]

Music

The harp, lyre, zither, drums, tambourine; the flute, oboe and reed instruments are, today, either exactly as they were used from earliest Arab civilization, or variations of the early musical instruments of the Arab world. The guitar and mandolin are sisters to that wonderfully plaintive, pear-shaped stringed instrument, the oud, played at Arab American parties today.

Interestingly, the bagpipe was first introduced into Europe by Crusaders returning from the wars in Palestine, and became identified particularly with the British Isles. Once the entertainment of the lonely Arab shepherd, the bagpipe returned to Palestine with the British Army. Several years ago, the international bagpipe competition was won by the bagpipe players of the Jordan Arab Army. This lost musical art was relearned during the period of Sir John Glubb’s (Glubb Pasha) re-organization and command of Jordan’s colorful Bedouin Corps.[27]

Arab poetry was put to music in the subtle delicacy of minor key sequences and rhythm, which today influence our ballads and folk songs.

Extempore poetry was perfected into musical expression, and Arab weddings and other happy occasions are still celebrated with extempore versing and musical composition.

Philosophy

Arab philosophers made little distinction between Faith and scientific fact, letting one exist within the framework of the other. The Arab philosphers, after Byzantium, and beginning with Islamic culture, re-discovered the classic philosophy of Aristotle, Plotinus and Plato in looking for answers to the fundamental questions of God’s creation of the universe, the nature and destiny of the human soul, and the true existence of the seen and the unseen.

Among the well-known philosophers of the medieval world were Al-Kindi, who built upon Plato and Aristotle; Al-Farabi who made a model of Man’s community; Avicenna (ibn-Sina) who evolved theories on form and matter that were incorporated into medieval Christian scholasticism; and Averroes, (ibn-Rushd) who inquired into the meaning of existence, providing Europe with its greatest understanding of Aristotle, and who, more than any other, influenced Western philosophy.

Averroes was called the “soul and intelligence of Aristotle” by ibn-Maymun, the great Jewish philosopher better known as Maimonides, who was responsible for the establishment of an Averroist school.

Thomas Aquinas, leaning heavily on the philosophy of Averroes, became Christendom’s leading expert on Arab doctrines.[28]

In discussing the accomplishments of some of the medieval Arab scientists, artists, educators, philosophers, poets and musicians, and their gifts to western civilization, we should remember that their own thought was in turn, molded and shaped by many ancient cultures — by Canaanite and other Near Eastern groups, by Egyptian, Greek, Roman cultures; and also by Chinese, Indian, and into the first centuries A.D., by some concepts of early Byzantium. Arab cultures, from the ancient to the present have given us three great monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. In government and law, we refer to Hammurabi, the Babylonian, and Ulpian and Papinian, the Phoenicians. Nearly six hundred pieces of Papinian’s writings were incorporated into Justinian’s Digest of Law of the sixth century, A.D. The first four women to serve in the Roman Senate were Phoenicians (Lebanese) and all took the name of “Julia” to honor Caesar.

Probably the single greatest contribution of the Arabs to the Western world was the phonetic alphabet which determines the course of our daily communication. In all the exchanges of our daily lives, then, in our homes, offices and universities; in religion, philosophy, science and the arts; we are indebted to Arab creativity, insight and scientific perseverance.

- Landau, Rom. Arab Heritage of Western Civilization. Published by Arab Information Center, New York, N.Y. -- 1962. pp. 1-40. ↵

- Ibid. p. 28. ↵

- Ibid. pp. 14, 31, 64. ↵

- Ibid. p. 35. ↵

- Islamic Heritage. Published by Esso Standard, Libya, Inc. pp. 21, 22. Undated. ↵

- Ibid. p. 22. ↵

- Landau, Arab Heritage, p. 33. ↵

- Ibid. p. 55. ↵

- Ibid. p. 56. ↵

- Islamic Heritage, p. 5. ↵

- Landau, p. 83. ↵

- Monroe, Joan. "Islam in Russia," Aramco World Magazine, January-February, 1976. pp. 6-12. ↵

- Landau, Rom. Arab Heritage, p. 42. ↵

- Ibid. p. 39. ↵

- Ibid. pp. 3, 7, 38. ↵

- Ibid. p. 44. ↵

- Islamic Heritage, p. 25. ↵

- Ibid. p. 25. ↵

- Glubb, Sir John Bagot. The Lost Centuries. Prentice-Hall, N.J. 1967. p. 295. ↵

- Landau. Arab Heritage, pp. 60-61. ↵

- Ibid. pp. 61-63. ↵

- Ibid. p. 85. ↵

- Islamic Heritage, p. 28. ↵

- Landau. Arab Heritage. p. 68. ↵

- Ibid. p. 74. ↵

- Ibid. p. 75. ↵

- Aramco World Magazine, May-June, 1976. "The World of Islam, Its Music." ↵

- Landau. Arab Heritage. p. 16. ↵