Main Body

II. “I Die an Innocent Man”: The Gruesome Death of William Beatson (1853)

James Parks traveled a long way and took considerable pains to commit the crime that led him to a Cleveland scaffold in 1855. Born James Dickinson in Bolton in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England, in 1814, he lived mostly at Clitheroe, Lancashire until his early twenties. Brought up as a farmer, he learned the craft of a weaver and eventually became caught up in the Chartist agitation which swept England in the 1830’s. He would later claim that he was involved in the printing and distribution of radical newspapers outlawed by the British government. But whatever his larger hopes for the future of England, he found himself unable to better his own condition and grew weary of working twelve hours a day in the heat of the harvest sun. He probably didn’t care, either, for the insides of English jails, where he apparently spent a few spells for some episodes of poaching in the late 1830’s. For whatever reasons, he left Lancashire in 1840 for a better life in the United States. The latter part of that year found him working as an overseer in charge of 40 girls in a weaving room at Bristol, Rhode Island.

Whatever wages Dickinson made at his new job were apparently not enough to satisfy his striving spirit. Sometime after quarreling with a man named Jim DeWolf, he learned that the tomb of DeWolf’s father contained a silver coffin and other valuables. Conspiring with a man named Gardiner, Dickinson contrived an audacious scheme. Rowing across an ocean bay through a driving thunderstorm in a skiff, Parks and Gardiner entered the cemetery grounds, scaled the high mausoleum walls and broke into the DeWolf family vault. Blowing off the coffin lock with gunpowder, they tore off the shroud and frisked the corpse for jewels, “an outrage hellish in conception and revolting to humanity in its execution,” as a Cleveland Herald chronicler aptly put it. Alas — the only valuable found was the silver coffin plate and the only further remuneration Dickinson received for a ghoulish night’s work was a six year term in the Rhode Island penitentiary for grave robbing and jail.

Dickinson subsequently claimed that he educated himself in the prison library but he doesn’t seem to have learned much. He soon returned to a life of crime, although he would always insist that he was unwillingly driven to it by the ineradicable reputation he carried as a jailbird. There may be some truth in this, as evidenced by the rueful regrets Parks expressed on the scaffold just minutes before his death:

Ah, there is where the circumstances that environed me, my eleven years in prison, my blackened character, flashed across my mind, and determined me in what I did. I had swerved from the path of duty and had lost what Solomon speaks of, in that good proverb, “a good name.” “A good name is better than riches.” Ah, how true! So long as your good name is yours, it will be a rock of defence against a thousand assailants, and without it, a single man shall put you to flight.

So it was probably only natural that Parks, falling in with some other ex-convicts in New Jersey, led a burglary gang into the house of a Mr. Kempton of Manyunk, near Philadelphia. Dickinson’s disguise as an Indian on that occasion did not deceive Mr. Kempton, however, and Dickinson soon found himself doing another stretch, this time in Pennsylvania’s Eastern Penitentiary. By the early 1850’s he was out of jail and living in Cleveland under the name of James Parks.

Parks’ activities in Cleveland before committing the murder that brought him notoriety are murky. It is alleged that he brought a female named Ann Carpenter here with him, that they lived together as man and wife — and that he murdered her when her presence became inconvenient to him. It was also rumored that he murdered a man and that he was arrested on a charge of adultery. It is known that he ran the Jenny Lind saloon on Pittsburgh St. for awhile and that he ran a rooming house for railroad hands in Berea. Late in 1852, however, he returned to England. There he married a cousin, Bessie Dickinson, said by one chronicler to be of “humble birth but unstained reputation.”

The path that led to a hangman’s noose opened up on February 13, 1852, when Parks and his new bride left Liverpool for the United States on the ship Constitution. Also on the vessel was a dissolute thief/confidence man from Yorkshire named William Beatson. What exactly happened during that fateful voyage was never documented in court or elsewhere. But it is known that a number of robberies of passengers occurred during the voyage — amounting to a value of several hundred pounds — and that James Parks probably knew that Beatson was the guilty thief. An even more likely explanation is that the two men were working together as a criminal team.

Several weeks went by after Parks and his wife arrived in Cleveland and established their bridal bower at Riley’s on River St. in the Flats. There were later suspicions that Parks was mixed up in the armed robbery of Joel Scranton’s house on the West Side in March, 1853 but his involvement, though probable, was never proven. Then, one day in early April, William Beatson showed up, flush with cash and anxious to see his old friend. Beatson claimed his impressive bankroll came from the sale of a farm; more uncharitable rumor had it that it was the illicit haul from yet another confidence game, this one practiced on an unsuspecting citizen of Buffalo. The truth probably didn’t matter to Parks: Beatson was buying drinks without limit and seemed happy to see him. And so, on the morning of Wednesday, April 13, the two men embarked on the bender that would culminate in brutal death for both of them.

Parks and Beatson were seen in a number of Cleveland saloons that day, throwing down drinks and carousing noisily. John W. Richardson, the keeper of the U. S. Hotel on River St. served them drinks about noon that day and would later recall at Parks’ murder trial that Beatson was already tipsy, although Parks remained relatively sober. Two hours later, Beatson aroused the ire of barkeep James Burton at his Pittsburgh St. saloon. Beatson, who was drinking brandy, began bragging about how much money he had and started flashing $50 and $20 gold pieces. Barton, who was afraid his inebriated customer might be robbed, told him to stash his money or get out of his saloon. As barkeep Richardson had previously noted, Beatson was thirstily swilling down brandy, while his careful companion continued to nurse modest glasses of beer. Sometime in mid-afternoon, Parks and Beatson departed, looking for further liquid refreshment and telling everyone they met that they were going to Pittsburgh.

They never got there. Embarking on “the cars” (as the new-fangled railroad was called at the time) with bottles in hand, the still-imbibing twosome got off the train at Hudson. Parks would later claim they disembarked by accident but train conductor C. C. Cobb later recalled that while Beatson was so drunk he could barely proffer his ticket, Parks seemed relatively sober. The two men then took another train to Cuyahoga Falls, where they walked to the American Hotel run by A. W. Hall near the falls.

Parks and Beatson stayed in Hall’s tavern room about an hour, drinking ale and smoking, while Parks bragged about the considerable cash his “brother-in-law” was carrying on his person. Parks spent the time trying to persuade Beatson to walk with him back to Hudson to catch yet another train, meanwhile making “many witty and jocose remarks” and maintaining enough sobriety to make Hall suspect that Parks intended to rob his companion on the darkened road. The decisive moment arrived at 11:02 pm, when Hall refused to furnish the two men any more alcohol and they departed, walking slowly down the road towards Hudson. Beatson was so drunk that he forgot his overcoat.

Neither of them ever got to Hudson. Perhaps the last person to hear, if not see them, was Mrs. Eunice Gaylord of Cuyahoga Falls. Sometime after 11 pm that April 13th, she heard two men outside her door arguing about directions. They were walking in single file about 15 feet from her house and the last words she heard was one of them saying, “No,” to which his companion replied, “We will go up and around.”

About 7 o’clock the next morning, two boys named Alley and Waters discovered large pools of blood about half a mile from the American Hotel and near where the railroad crossed both the road and the Cuyahoga River. Other searchers soon arrived on the scene to find, under the abutments of the bridge, a vest button, a cane, human brains and a great deal of blood splashed head-high on the abutments. There were two sets of muddy footprints leading under the bridge — and only one set leading out towards the river, towards which something heavy and bloody had been dragged. In a nearby canal they found a suit of men’s clothing cut to pieces and a man’s cap on a stump in an adjoining field. The clothing was soon identified as belonging to the man who had been so drunk at the American Hotel the previous night and the hue and cry was out for James Parks even before William Beatson’s headless, naked corpse was found the following morning, floating in the Cuyahoga River.

Meanwhile, where had his erstwhile drinking companion gone? Parks’ trail was first marked by a canal boat driver, who saw him walking by the towpath about midnight. Another driver saw him three hours later and at 8:30 on the morning of April 14, at a stable two miles from Akron, he hired a rig from Hiram Corey to take him to Ohio City. That was about nine hours after Beatson was last seen alive. Parks explained his blood-covered clothing to Corey with the story that he had fallen off a canal boat coming from Pittsburgh and bloodied his nose. Later that afternoon, Parks was seen in Ohio City, inquiring for an Englishman named Clark and he spent the following two days in Cleveland before departing for Buffalo, followed two days later by his wife and brother. There he was arrested by Joseph Tyler at an English grocery on Monday, April 18 and brought back to Cleveland. The canny Tyler, who had traced Parks by shadowing the eastward flight of his wife and brother-in-law, had also brought along a handbill featuring Parks’ description, which he triumphantly flourished when Parks denied his identity. Surely, Parks’ appearance on this dramatic occasion must have been the last word in Victorian melodrama:

[He] is an Englishman, thick set, about 5 feet, 6 inches high, had on a low plush black cap, black sack coat, black pants, black satin vest, had lost one or more of his upper front teeth and is apparently 35 years of age.

The conclusive detail was the missing teeth, which Tyler shrewdly verified by sticking his hand in Parks’ mouth. Tyler’s lack of delicacy would pay off later when he collected the $500 reward by the Summit County Commissioners for Parks’ capture. The next day, Parks’ wife and brother were captured in Rochester with more than a thousand dollars in gold and bills on their persons.

Indicted for first-degree murder in July, Parks’ trial on a charge of first-degree murder commenced at the Akron County Courthouse in late December, 1853. Ably defended by lawyers George Bliss, Christopher P. Wolcott and W. S. C. Otis., Parks was prosecuted by William H. Upson, Lucius V. and Sidney Edgerton, with the Honorable Judge Humpresville presiding. Parks’ defence, as a Plain Dealer scribe later put it, was “most remarkable, almost unprecedented.” Claiming that he and Beatson had decided to veer off the Hudson road and take the more direct route of the railroad tracks, Parks swore that Beatson had met an accidental and unexpected death when the two of them fell twelve feet in the dark through the widely-spaced wooden planks of a railroad bridge spanning the road. (In fact the planks were no more than 12 inches apart.)

Although injured himself by the fall and entirely innocent of Beatson’s death, Parks, still haunted by his jailbird past, was convinced that no one would ever believe that he had not plotted and executed his companion’s demise. So there, in the darkened, rainy gloom of that April night, Beatson stripped off Beatson’s clothes and cut off his head to make identification as difficult as possible. He then took to his heels, hoping for the best and fearing the worst.

There were no eyewitnesses to back up Parks’ lurid story and it is probable that his past irreverence in the matter of corpses — the DeWolf affair — may have told against him. So, too, did the testimony of expert medical witnesses, who found the injuries to Beatson’s ill-used corpse incompatible with a single fall of twelve feet: a total of four wounds made with a knife, a pistol, a stone and one unknown weapon. It was further established in court that some of the injuries were inflicted while Beatson was still alive. Nor could the grisly fact that the victim’s missing head was never found have favorably prejudiced the jury of twelve men in Parks’ favor. They must have also, doubtless, taken a malign view of the considerable amount of cash found in the possession of Parks’ wife and brother-in-law when they were apprehended in Buffalo, a golden windfall whose provenance neither Parks nor his wife were able to explain. Ultimately, the jury accepted the prosecution’s assertion that Parks had deliberated lured Beatson to a lonely locale to murder and rob him.

Swiftly convicted and sentenced to hang, Parks won an unexpected, indeed freakish, reprieve when his verdict was overturned by the Ohio Supreme Court. Noting fussily that his jury’s announcement of its verdict had only been “Guilty” — instead of the prescribed “Guilty of Murder in the First Degree” — the Court granted Parks a new trial. With a change of venue to Cuyahoga County to avoid severely aroused local prejudice, the same evidence was presented to another twelve good men and true in March, 1855 with the same result. With Judge Samuel Starkweather presiding and lawyers Hiram Griswold and Amos Coe defending him, Parks’ second trial was highlighted by the rhetorical forensics of County Prosecutor A. G. Riddle, whose closing speech against the accused drew the admiration of a worshipful Cleveland Leader reporter:

His argument was logical, his diction gorgeous, and his eloquence splendid. His reasoning was close and convincing, like that of Choate; his eloquence sublime, subduing, like that of Prentice. He possesses the powers to charm with eloquence and to ensnare the mind with his reasoning.

Perhaps due to Riddle’s persuasiveness, the jury only took five hours to convict Parks on the first of the four capital counts against him, that he had murdered William Beatson by a stab in the neck with a knife. It couldn’t have been much consolation to Parks that the jury cleared him of the remaining capital charges.

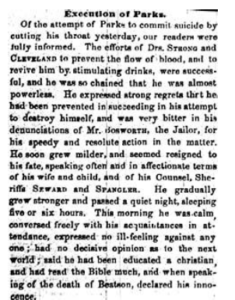

Bitterly proclaiming his innocence, Parks schemed to the end to avoid his fate. A week before his scheduled execution, the head of a broken key was discovered in an inner door of the Cuyahoga County jail cells. Interrogation of the prisoners disclosed that Parks had tried to bribe a fellow prisoner to obtain a key and effect his escape. When pecuniary inducements failed, Parks threatened to kill the man unless he aided him and only the unexpected breaking of the key in the lock aborted the desperate plan. Then, just the day before his scheduled execution, Parks tried once more to cheat the hangman. Suddenly shouting, “This mortal man must die; you can’t save me now!” Parks slashed his throat with a three-inch knife, probably smuggled into his cell by his still-smitten wife. Although he succeeded in gashing his jugular vein badly enough to spew “great jets of blood” about his cell, jail physician Dr. Robert Strong managed to stop the bleeding and preserve his patient for judicial death. Not that his patient was grateful for the assistance: “God damn your miserable soul; let me alone!” is what Parks is reputed to have said as Strong and jail turnkeys struggled to subdue and pinion the suicidal prisoner.

Parks conducted himself better on his last day, June 1, 1855. Insisting on his complete innocence to the last, he finished a final cigar and walked calmly from his cell to the scaffold at 11:54 am, accompanied by Sheriff Miller S. Spangler, Deputy Bosworth and United States Marshall Jabez Fitch. The scaffold, built by J. M. Blackburn and placed in the jail hall facing Public Square, was a platform eight by five feet, about eight feet high and surmounted by an eight-foot frame for the gallows proper. It would be used to hang six more men in Cuyahoga County over the next 24 years, not to mention several from other counties. There, after a restorative glass of wine, Parks sat in a chair with a rope around his waist while he was permitted to speak to the crowd of forty persons assembled in the jail yard, the fortunate few culled from the crowd of several thousand disappointed spectators gathered outside the jail gates.

Parks’ oration was described by commentators as short — but that must have been only by the heroic standards of the age, as it seems to have lasted for over an hour. Swearing that he had been misrepresented by the press, he insisted that his version of Beatson’s death was accurate in very detail and that “as I stand before my God, I speak the truth.” Speaking of his aged parents in England, he begged that they not be informed of his disgraceful end and spoke with feeling of his infant child and dear wife: “I had never known her virtues had it not been for my sad misfortunes.” At this juncture, so moved was his crowd of witnesses, that the proceedings were interrupted so a collection could be taken up for the impending widow Parks. It yielding $49.66, Parks continued in his understandably lachrymose vein:

I assure you that I do not deserve this fate. No man has a kinder disposition, no one whose life is freer from cruel acts . . . I leave the world at peace with all mankind, without censure upon any one.

Concluding his remarks about 1:00 pm, Parks sipped another glass of wine while his hands and feet were fastened and the rope secured around his neck. Granted permission to give the death signal, he waited patiently while the black cap was put over his head and then, at 1:04 pm, he dropped his handkerchief, crying, “I die an innocent man!” A second later, the drop opened and he fell six feet down through it like a stone. There was no evidence of struggle or pain and when the corpse was cut down at 1:40 pm Drs. Strong and Cleveland found that the neck had been cleanly broken by the drop. Following his last wishes, Parks’ body was removed from the view of the gawking crowd, given a fresh shave, prepared for burial and turned over to his grieving widow.

Only two more comments need be appended to afford a balanced measure of the pathetic James Dickinson Parks. One is his own self-serving lament, a final apologia written just before his execution and intended as his manifesto to a misunderstanding and murderous world:

When I meet Christ in the Kingdom of Heaven, he will congratulate me, for my case is parallel with his, with only a little exception. There were only two false witnesses against him; and there were some twenty that were false witnesses against me: but I attribute that to the alteration of the statutes and the increase of population since Christ’s time; for when he was tried they hunted the whole kingdom and could find but two . . . They set up over Christ’s head his accusation written thus: “This is Jesus, the King of the Jews”; but they will set up over my head, I suppose, my accusation, written thus: “This is James Parks, the murderer.” But it may all be true of Christ; but it is a lie concerning me.

The other comment came from the editorialist of the Cleveland Herald on the day after his hanging. Noting Parks’ protestations of guilt in the face of overwhelming circumstantial evidence and his inability or unwillingness to explain his motives, the editorialist opined sourly on his behavior in the shadow of the gallows:

A desire for notoriety, an itching desire to have his name continually in the papers, has characterized him for the last two years. That his nature was brutal, every circumstance shows, while no action indicates the talent of the “accomplished villain,” or any sympathy for humanity.