Main Body

IX. “She is Not Dead To Me”: The Fatal Passion of Charlie McGill (1877)

Charlie McGill’s path to the gallows, perhaps befitting Cleveland’s 1879 maturity as a city, led through a whorehouse. Laura Lane’s brothel on Cross St. (East 9th just south of Carnegie Ave.) to be exact — although he wasn’t there for what you might think on December 2, 1877. He had come there for that the previous evening, spending the night in his sweetheart Mary Kelly’s bed and — according to her fellow prostitute, Mary Campbell — he spent some of those hours weeping. Well he might have, for Charlie McGill was an unhappy bachelor that late autumn of the Gilded Age. At least part of his purpose in coming to see Mary was to persuade her to give up her lucrative life of shame and rejoin him in the life of poverty and privation she had once shared with him. Now it was the next day, Sunday noon to be exact, and Mary remained deaf to his importunate pleas. For now, though, the argument seemed exhausted and Mary turned her back on Charlie to doze off again on the bed on which they lay in her second-floor chamber.

The argument was over, but not in the way Mary anticipated. Several minutes passed, then suddenly, Charlie rose on the bed, put his knee on Mary’s chest and pulled out a seven-shot revolver from his pocket. Without a word, he pressed it against Mary’s head and pulled the trigger. He was blinded by the flash of the powder and momentarily deafened by the gun’s report, and the next thing he recalled was hearing Mary scream, “Go get a priest!” and, turning her blood-streaked face towards him, “Charlie forgive me!”

It is safe to say that Charlie did not. As he so pithily put it later, “I let her have the rest of ’em in the face and neck. I shot her and kept shootin’ and shootin’ and shootin’ until the revolver wouldn’t shoot anymore.” And he wasn’t indulging in airy hyperbole: Charlie blasted six more slugs into Mary’s face and neck. Then he calmly reloaded the empty revolver with four more bullets and fired those. The powder flash from the first round set her dress on fire and Charlie smothered it out. The second set the bedsheets aflame, but Charlie calmly extinguished the fire before carefully aiming the last two shots into her heart. He would always insist that he had meant to save the last bullet for himself but he seems to have forgotten the noble intention in the heat of the moment.

Charlie’s activities had not gone unremarked. Mary Campbell, who had generously loaned her bedroom to Charlie and Mary, was sitting in the parlor below with the house madam Laura Lane when ominous sounding noises from above prompted Lane to send Campbell to investigate. Opening the bedroom door, Campbell saw Charlie with his gun to Mary’s head, his knee on her chest and Mary crying and screaming. Campbell apparently didn’t take Charlie McGill’s antics very seriously, because she said, “For God’s sake, don’t make so much noise on a Sunday!” Then the first round smashed into Mary’s head and Mary Campbell departed for the police, screaming bloody murder all the way down the street.

Meanwhile, having finished his sanguinary labor upstairs, Charlie arose from the bed, came downstairs and carefully washed his bloody hands. Then he returned to the corpse and kissed Mary’s face tenderly, or at least what was left of it. By now Laura Lane’s house of ill-fame was thronged with excited neighbors who had heard the eleven shots, and to all of them Charlie made the same declarations: “I done it! Have I finished it well? I done it.” It was clear, even before the police arrived later and took Charlie away, that it would be difficult for anyone to save Charlie McGill from a Cleveland hangman’s noose.

The murder of Mary Kelly in a Cross St. bagnio sent shock waves through the moral and legal milieus of Gilded age Cleveland. For moralists it was an object lesson of the perils facing the hordes of rootless young men and women drawn to the burgeoning Forest City in the 1870’s. Those perils included drink, fast women and the unsupervised courtship of the sexes, precisely the dangerous components that saturated the Cross St. tragedy. To lawyers and law buffs it was a dramatic case study on the complex topic of insanity as a legal defense and how it should be proven or disproven in a criminal court. And for everyone else it provided raw, prolonged, very delicious scandal, as the seamy details of the sordid lives of two pathetic loving losers were paraded for months in the columns of Cleveland’s daily newspapers.

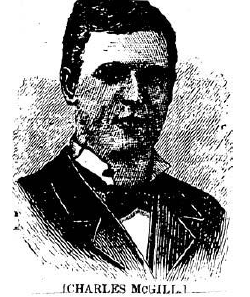

Charlie McGill was perfectly cast for the role he played at 100 Cross St. Coming from a solid middle-class Athens County family of nine children, the 27-year-old Charlie turned onto the path of sin quite early in his misspent life. Possessed of a hair-trigger temper and chronically restless, Charlie was a sickly, bellicose child, subject to bouts of sleep walking and ill-health which kept him frequently bedridden. After an unsuccessful attempt to train him in his father’s craft of cabinet making, Charlie was sent off to Ohio University in 1864 to acquire a gentleman’s education. The only education he acquired in his two-year stint there, however, was a precocious mastery in the consumption of alcohol and the pursuit of venery. Returning to the family bosom in 1866, Charlie sponged off his long-suffering relatives until his father’s death in 1868. After that, Charlie abandoned all restraint, plunging into a career of “riotous living” much like that enjoyed by the late Dr. John Hughes, if lacking the latter rogue’s gentrified pretensions.

Like many a weak man, Charlie sought his salvation in a good woman — and like most such men, succeeded only in ruining her life, too. Meeting and marrying Miss Louisa Steelman of Columbus, Ohio shortly after his father died, Charlie tried to settle down into habits of bourgeois domesticity. Within a couple of tempestuous years, however, the McGill marriage had settled into a predictable routine of drunken fights (Charlie drunk, Louisa sober), physical abuse (Charlie giving, Louisa taking), periodic separations and brief reconcilations. Although he sometimes worked at casual jobs on the local railroads and as a hardwood finisher, it was an open scandal that Charlie provided little financial support for his wife and two children.

By the early 1870’s dissolute Charlie McGill was also well-known to the Columbus police. Charming during his increasingly infrequent periods of sobriety, Charlie was a demonic brute when in his cups and was notorious for the destructive mayhem he caused in local saloons. Renowned for his willingness to take on multiple antagonists in barroom brawls, Charlie was especially celebrated by fellow barroom pugilists for an incident in which he pistol-whipped a drunken soldier with his own revolver. Known to Columbus lawmen as a “low sort of gambler, a beat of the worst sort and a rowdy who never missed a fight,” Charlie was further identified in police blotters as a shill employed to lure “greenies” into the clutches of cardsharps and as a despoiler of very young females.

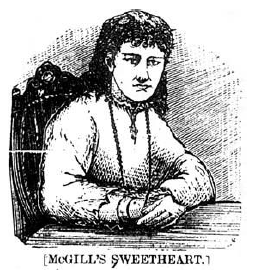

How a girl like Mary Kelly became fatally intertwined with a man like McGill is one of those mysteries of biology and fate that makes stories like this possible. Raven-haired, provocatively sexy and 19 years old when she met Charlie in 1872, Mary was the daughter of a reputedly respectable Columbus family. But something decisive, if unknown, occurred during her adolescence to cloud both her reputation and prospects. One story was that she was seduced and abandoned at 14 by a career criminal named David Lawson; another rumor had it that Mary had been more or less sold to the same villain in a callous effort to recoup the family fortunes. Whatever the truth, Mary was living in Columbus in 1872, working as a seamstress, servant and sometime streetwalking prostitute.

Charlie fell quick and hard for Mary, from the moment that he first saw her showcasing her attractions on a Columbus street. Soon after they met, Charlie completely abandoned Louisa and his children and set up light housekeeping with Mary. There were some minor setbacks: Charlie wanted Mary to cease her commercial sex activities and she failed to prevent at least one, brief reconciliation with the long-suffering Louisa. But by the mid-1870’s Charlie and Mary had settled into more or less common-law conjugal regularity, if not quite felicity.

It couldn’t last. Charlie sincerely loved Mary, at least according to his own rather dim lights. But his downward mobility had not ceased its acceleration even after she came along and she eventually found she couldn’t live with a chronic, mainly unemployed alcoholic. Mary, too, genuinely loved Charlie — but she didn’t like nearly starving to death in Columbus with him. She didn’t like it any better in Toledo in 1876, where she gave birth to a child, whose arrival could only have aggravated the precarious family finances. The child was soon shipped off to someone else’s care and Mary and Charlie struggled on: Mary working as best she could in domestic service jobs and Charlie drinking away her wages as fast as she brought them in. In the spring of 1877, they decided to try their luck in Cleveland.

Bustling, growing, big-city Cleveland must have seemed like a better opportunity for the hard-pressed couple. And it was — for Mary. Soon finding work as a valued servant and seamstress in several respectable Cleveland homes, Mary was now exposed to more luxuries and more comfortable modes of living than she had ever known before. But at the very time her horizons were expanding, Charlie’s were contracting. His undisciplined drinking had only gotten worse over the years since he had met Mary, and his failure to find lucrative employment in Cleveland seems to have silenced forever what was left of the better angels of his nature after more than a decade of intense dissipation. As spring turned into summer, his behavior to Mary, aggravated no doubt by his resentment of her relative economic success, worsened. He began physically abusing her in public and trying to get her fired from her domestic situations in Lake Ave. mansions.

The inevitable smash came on October 13, 1877, when Charlie beat Mary severely and tore her clothes off in a drunken rage while they were in a bedroom at 18 Johnson St., where the couple often met to have sex. Telling him that she was leaving him forever, Mary departed, quit her remaining legitimate jobs and disappeared — she hoped — into the anonymity of ever-expanding metropolitan Cleveland.

Charlie McGill was not used to taking the word “no” from women and Mary’s rejection stimulated him to the last act of cleverness in his life. Over the next six weeks, he spent much time attempting to track down her whereabouts; he would later boast that he had spent $18,000 in the quest, but that is no doubt a typically ludicrous piece of McGill prevarication. His sleuthing finally paid off on December 2, when, in answer to a series of faked letters (purporting to be from one of Mary’s friends) sent to General Delivery in numerous Ohio cities, Mary picked up one of the epistles from a downtown Cleveland post office. Charlie had Mary tailed for the next few hours and thus it was that he showed up that afternoon at Jack Willis’ Broadway Ave. saloon in time to catch Mary drinking at a table there with one of her friends.

Maybe it was loneliness, maybe it was the drink. Maybe she was just paralyzed with fear. But it’s a fact that Mary might have saved her life if she had immediately fled from McGill in that saloon. But she didn’t, and, soon, thawing under the influence of alcohol and perhaps McGill’s residual charm, she gave him her address: 100 Cross St., just a couple of blocks away. She also gave him permission to call upon her there. She then left the bar, perhaps encouraged that Charlie did not attempt to stop her. She might have thought differently if she had seen Charlie, as Jack Willis did, shake his fist after her and mutter, “I’ll fix you yet!”

Charlie McGill would later claim that he had no idea that 100 Cross St. was a brothel or any suspicion that Mary had returned to her former avocation until he arrived at the door of Laura Lane’s house of joy that Saturday night, December 1. To say the least, this seems unlikely: Charlie McGill was an hardened habitué of such places and he must have also been aware that he himself had worked very hard to ruin Mary’s opportunities for legitimate employment in respectable places. Be that as it may, Charlie was in a good mood when he showed up at Laura Lane’s establishment that night. Accompanied by a male friend with the improbable name of Elliot Hymrod, Charlie was the life of the party, generously lavishing bottles of alcohol, cigars and good cheer on the inhabitants of the house, including proprietor Laura Lane and Mary’s special friend, Mary Campbell. Apparently his cheer did not last, as Campbell’s recollection of his nocturnal weeping attests, but he and Mary seem to have passed the night otherwise peacefully in her bed at 100 Cross St.

Leaving at 9 the next morning, the still-affable Charlie promised to return. And for once, he was a man of his word. Going to Charlie Stein’s pawnshop on Ontario St., Charlie pawned a coat he had borrowed from his friend Elliot for $5. He then used the $5 to purchase a seven shot revolver and a box of suitable cartridges from Stein. Just to make sure, though, he got permission to test-fire three shots down into Stein’s basement. Satisfied with the revolver’s performance, he put the gun in his pocket and left for Cross St.

Charlie returned to Laura Lane’s house about noon and asked Mary Campbell if he and Mary could use Campbell’s room for a “private purpose.” The purpose, as Mary soon found out, was for Charlie to persuade her to give up her life of sin and come back and live with him. We have only Charlie’s version of the ensuing conversation but his recollection of their last colloquy is consistent with the self-righteous, egotistical selfishness he had ever displayed in the known episodes of his life. Assuring Mary that things would be different, he promised to support her in palatial style and appealed to her finer instincts, pleading, “For God’s sake, Mary, leave this house! What would your grandma and auntie say, if they knew how you are going down?” Charlie was particularly upset to hear just how financially well Mary was doing in her current occupation, and he begged her desperately for the next hour to come back to him. But Mary was adamant. She had heard it all before and the memory of the continual privations she had suffered during her years with Charlie were an aching, stark contrast to her present comfort and independence. Tiring of his pleas and promises, she turned her back on Charlie and the room subsided into silence.

Several minutes later, as previously chronicled, Charlie shot Mary to death. Having bragged openly to everyone who responded to the undue commotion in the house, he boasted further to Dr. Norman Sackrider, the physician who came to examine the corpse, carefully explaining the exact sequence of his shots and the wounds they had inflicted. Sackrider cautioned McGill not to say anything self-incriminating but nothing could stop the verbose Charlie, who insisted on recounting the details of Mary’s murder to anyone who would listen. Patrolman William Schnearline eventually carted him off to jail, where Charlie continued his repetitive narrative to interested lawmen and reporters. Like William Adin, he had no qualms about admitting his premeditation and malicious motive. His recorded comments included:

I shot the [eleven] shots and would have shot ten more if necessary . . . I was determined to make a sure thing of it . . . I’d do it again if things were in the same shape.

Curiously proud of his afternoon’s work, Charlie refused to change his bloody shirt, telling Elliot Hymrod, who visited him in cell, “I would rather not. This is her blood and I love it.” And to the day he died, more than a year later, Charlie McGill would wear a piece of cloth encrimsoned with Mary’s blood next to his heart.

Once Charlie’s initial enthusiasm calmed down — perhaps intensified by smoking 27 cigars during his first day in his jail cell — it became clear to most observers that Charlie and his lawyers were carefully laying the groundwork for an insanity defense. The verbose boasting about the details of the murder continued but they were now supplemented by an almost constant twitching of his head, lolling of his tongue and like physical oddities.

Charlie insisted that the turnkeys set a place for Mary every time he dined in his cell and daily talked a gothic blue-streak concerning his alleged nightmares about Mary. As he told a Plain Dealer correspondent:

He dreamed that he was in a house on Johnson Street where he used to meet [Mary], that she came in, sat on his lap threw her arms around his neck and kissed him. Then she pointed to spots on her face (where the bullet marks are) and told them they must be sores which broke out during the night.

Indeed, within a week of his arrest, it is safe to say that Charlie had developed a sort of baroque gift for his mummery of mental illness, telling another correspondent:

I am so glad to see you always. When you come, do so in the daytime, as you have today. I am busy, very busy at night. Write letters early in the evening, then go out. Last night was up at the Post Office. The letter-carriers had a big dance there. Jennie and Kittie Elliot and Mary and I were there and had good time.

At the close of the dance we got to writing letters to each other and dropping them into our boxes . . . The night before Mary and I went over the high bridge, and there somewhere we found a great high place where there were about a thousand stars leading up so very high, and we went up them, and there we found a million people, all dressed in white, and all were happy. But Mary fell down and cut her face, and it was all bloody. They say that is a bad sign but I hope it is not.

And to all his visitors, Charlie flourished a bloody handkerchief, saying it was stained with Mary’s blood and that he would not part with it for $1,000.

Worse yet, perhaps, Charlie, like Dr. Hughes before him, found his poetic muse stimulated by his sojourn in a Cleveland jail. Not content with daily singing his verses aloud in his cell, McGill was gratified to see his literary effusions on his late lover blazoned forth to the Cleveland public in several of its major newspapers:

“To Mary K.”

Tho’ lost to sight, to memory dear

Thou ever will remain,

One only hope my heart can cheer,

The hope to meet again.

Oh, fondly, on the past I dwell,

And oft recall those hours,

Where wandering down the shady dell

We gathered the wild flowers.

Yes, life then seemed one pure delight

Tho’ now each spot looks drear;

Yet though thy smile be lost to sight,

To memory thou art dear

Charlie McGill’s much-anticipated trial didn’t disappoint connoisseurs of legal forensics. Held before Judge Jesse H. McMath, McGill’s stellar defense was fought by Samuel E. Adams, who was opposed by Prosecutor John Hutchins. Characterizing the histrionically twitching McGill as a congenital madman, Adams paraded Charlie’s mother, several brothers and about a dozen shirttail relations to depone that Charlie had been crazy from birth. Citing his childhood somnambulism and his chronically ungovernable temper, Adams and his witnesses tried to paint a picture of a permanently deranged defective, his physiological development perhaps ruined by medicinal arsenic passed to the developing Charlie through his mother’s breast milk. Adams also cited the potential brain damage McGill may have suffered in August, 1877 when he drunkenly provoked a squad of Cleveland cops into beating him senseless with their nightsticks at a Cleveland beer garden.

But such testimony was undercut by prosecution witnesses, who testified that they had never noticed any changes in Charlie’s behavior that couldn’t be explained by the effects of chronic alcoholism. Dr. Proctor Thayer made his usual appearance as a State witness and startled the prosecution by opining that Charlie’s courtroom symptoms of mental aberration could not be faked. But Judge McMath himself threw cold water on that charade, pointedly warning the jurors in his instructions that they were to “receive with great caution that class of testimony tending to show what has been said or done or written by the prisoner since the commission of the act.” The important thing, McMath stressed, was not Charlie’s alleged eccentricities but the material facts of the case: “Does the evidence satisfy you that the shots were fired with a design to kill the deceased?” And Charlie himself probably laid it on too thick: his twitching noticeably intensified with every day of the trial and he could sometimes be heard asking his aged mother when Mary Kelly was going to appear in the witness box.

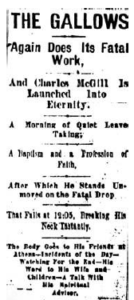

Whatever their estimation of Charlie’s motives and methods, his jury didn’t buy his insanity defense. After going out in the early afternoon of February 28, 1878, they returned at 9 am, March 1 with a verdict of Guilty of Murder in the First Degree. That same day Judge McMath sentenced Charlie to hang on June 26.

As it happened, Charlie McGill’s justice was delayed, if not ultimately denied. There had been great difficulty in seating Charlie’s jury and, after exhausting several venires, Judge McMath had allowed Eli Stephenson of Parma to be seated, instead of his son of the same name who had actually received the summons. Sure enough, this defect resulted in McGill’s conviction being overturned on appeal, causing a Cleveland Press writer to complain:

If Mary Kelly had been one of Euclid’s aristocrats or an officer of the state or county, how quickly McGill would hang, and what little pains would be taken to save him. But she was a poor, unfortunate, weak Irish girl, hence the fuss made in favor of her seducer and murderer.

The Press editorial probably accurately reflected outraged middle-class opinion, which had been shocked by Samuel Adams’s seamy, if predictable indictment of Mary Kelly’s moral character by way of mitigating his client’s crime. Repeatedly characterizing her as a “brazen-faced Cyprian” (a period term for prostitute), Adams had throughout the trial characterized McGill as her victim, the brassy homewrecker who had spurned Charlie’s belated attempts to make her an honest woman of her. Of course, given the times, even Adams had to be careful about not rubbing the public’s nose too much in matters polite society tried to pretend did not exist. The prudish constraints imposed on his attempt to blacken Mary Kelly’s memory were hilariously highlighted by his awkward cross-examination of Mary Campbell:

Adams: What is your business?

Campbell: I don’t know what you mean by that.

Adams: Will the Court explain it to her?

Campbell: I do everything.

Judge McMath: This coming from a female, I suppose, Mr. Adams, you understand what that means?

McGill’s second trial, like James Parks’ repeat performance, seemed a gratuitous formality. Although it took a pool of 500 jurors to yield the twelve men required, they were eventually secured, and they efficiently found McGill again Guilty of Murder in the First Degree on October 26, 1878. One noticeable change this time around was that Charlie dropped all pretense of mental illness, watching quietly and twitchless as the same witnesses and experts repeated their damning testimony before Judge Darius Caldwell. By this time, perhaps reflecting his growing pessimism about his legal prospects, Charlie had embraced the comforts of religion and was fulsomely spouting words of pious resignation right and left.

As verbose in his supposed repentance as he had formerly been in his maniacally murderous boastfulness, McGill told his many death cell visitors that he was “the happiest man in town” and that he looked forward to soon seeing Mary in a better world. It may be assumed, therefore, that Charlie McGill enjoyed heightened transports of delight when word came down on February 11, 1879 that Governor Bishop had refused to commute his death sentence.

Fifty lucky Cleveland residents traipsed into the Cuyahoga County jail on February 13 to see McGill expiate his awful crime. Having dined “heartily” on a last meal of fried oysters, ham, eggs, assorted vegetables and coffee, McGill was said to be the calmest person present as he strode through the courtyard and mounted the gallows. Submitting docilely while his limbs were pinioned and the black cap put over his head, the mechanically-inclined Charlie pronounced Albert Hartzell’s brand-new gallows “very nice” and tried to keep up the flagging spirits of his spiritual counselor, the inevitable Rev. Lathrop Cooley. His last words, as he stepped to the drop, were to Sheriff John Wilcox, a cautionary, “Now, don’t you make any mistake about that rope.” Wilcox didn’t: when the drop opened a few seconds after 12:04 pm McGill’s neck was broken instantly as he flew through the nine-foot drop. Fifteen minutes later, his body was taken down, autopsied and put into a coffin for shipment to Columbus. The verdict of the attending New York Times correspondent was that McGill’s hanging was “undoubtedly the most humane, orderly and systematic of any ever conducted in Ohio.”

McGill’s grave lies far from Mary Kelly’s resting place in Woodland Cemetery but Charlie left behind a few noble sentiments as a kind of memorial to the woman that he loved neither wisely nor too well. One was a posthumous statement, expressing the wish that his example might be a profitable one to men embarked on a similar moral path. Not that he was too confident about its moral suasiveness: “But I know they won’t. They will keep on and say there will always be plenty of time to repent. Then they’ll die for their sins.” McGill’s other tribute to Mary was a more personal gift, a last poetic effusion from his inimitable muse:

“She Is Not Dead”

Although she sleeps beneath the sod,

No headstone there to show,

Above her quiet resting place

The gentle zephyrs blow; Although the bitter, burned tears

From ‘neath my eyelids start,

Still, still, she is not dead to me,

She lives within my heart.