Main Body

III. Tamsen Parsons’ Long Fatal Love Chase: The Insufferable Dr. Hughes (1865)

Like James Parks, John Hughes came a long way to dangle on a gallows for a select Cleveland audience. And like Parks, Hughes’ bloody doings were much mixed up with the excessive use of alcohol. But the similarities end there. Parks came out of the Yorkshire peasantry; Hughes was a scion of moneyed aristocracy. The prelude to Parks’ slaughter was a bumbling life of largely unsuccessful petty larceny; Hughes misspent his life, throwing away every advantage birth and fortune can provide. Parks slew for money; Hughes killed for what he called “love.” And while Parks butchered a criminal hardly any better than himself on a dark and stormy night, Dr. Hughes stalked and slaughtered sweet 17-year old Tamsen Parsons within sight of her parents’ Bedford doorstep in broad daylight.

Born in 1833, Hughes was the spoiled, only child of rich gentry on the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. Sent off to boarding schools at four when his father died, John reached adulthood with well-practiced passions for drink and venery. After toying with several careers, the dilettantish Hughes joined Her Majesty’s 5th Dragoon Guards in time to fight bravely in the Crimea, where he was badly wounded at Balaklava. Returning home, he acquired an unsuitable wife after a girl of good character scorned him, and returned to his habits of dissipation. He did manage to acquire a medical degree in the late 1850’s but in 1860 he decided, after drinking and gambling away his ancestral estate, to try his luck in the United States.

Joining the considerable Manx community in Cleveland, Hughes quickly earned repute as a questionable physician and certified binge alcoholic. Often seen performing operations while under the influence of drink, he was once observed on his way to an amputation armed only with a butcher knife and a mechanic’s saw. After bringing his wife and infant son Bissel to Cleveland in 1862, Dr. Hughes joined the United States Navy. His sojourn there prospered not, and two subsequent stints as an oft-inebriated surgeon with the U. S. Army ended with his final discharge and return to Cleveland in the fall of 1864.

Hughes later claimed he returned to the Best Location in the Nation to find his wife a hopeless sot and his home a desolation. Whatever the truth of these assertions, the good doctor, typically, sought solace in the bottle. Several nights of hard drinking eventually led him to a Soldier’s Ball in Bedford, where he cut up old ties with acquaintance Thomas Parsons and enjoyed libation after libation into the wee hours of the morn.

Hughes’ next memory was of waking up in a bed at the Parsons’ house in Bedford, doubtless with an emphatic hangover. A beautiful young woman was leaning over him, and then she lifted his pillow and loosened his cravat. It was love at first sight: Hughes looked up blearily and said, “Who are you?” “Tamsen Parsons,” replied the girl, who then asked a question which has puzzled chroniclers of John Hughes to this day: “Doctor, why do you drink so much?”

Never at a loss for words, the glib Hughes rapidly unfolded a tale of unmitigated marital purgatory to the impressionable 17-year-old Tamsen. His marriage was a joke, his home life a hell, he sobbed, and he hardly knew how to go on. And, apparently, Hughes’ maudlin malarkey had its intended effect. As he finished his yarn of lies, he later recalled, the beauteous Tamsen put her head on his bosom and sighed, “Would to God I were your wife!” Happily, her sentiment resonated well with the severely dehydrated Doctor, who remembered it to his dying day: “I saw in that look sympathy and pity that filled my whole soul, and I saw my feeling reciprocated.”

Who were these star-crossed lovers whom a malign Fate brought together? Of Tamsen, unsurprisingly, we know little: it is an ironic inequity that most murderers are far better known than their victims, and it is a kindred truism that 17-year olds are generally woefully lacking in biography. Tamsen, by all accounts, was young, beautiful and impressionable — and there was no blemish on her public character before she met John Hughes. Our picture of Hughes is clearer, limned vividly as it was in the later light of public notoriety:

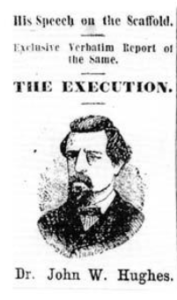

[Hughes] is a very good looking man . . . [He] stands erect, a powerfully-built man of five feet, ten inches in height, with a good head on his shoulders and a face which bears the mark of intelligence and resolution. His hair, which is not plentiful, is black, and he wears a becoming moustache and goatee. His eyes are very large and full and of a blue color, not quite clear, but somewhat muddy. . . . When he speaks, no matter how briefly, he impresses you as one who weighs his words well, and there is that in his every attitude, motion and speech, which suggests that he could, on occasion, be a man of courteous manners and elevated conversation.

Not everyone agreed with this gladsome newspaper portrait of Dr. Hughes. Another reporter allowed that much about him suggested the figure of “the Apollo,” but opined further that his eyes could look “venomous” and that “the right eye looked larger than the other, owing to the fact that it was once knocked so far out that it hung upon the cheek.”

Whatever his true merits, it is indisputable that Tamsen fell hard for the Doctor twice her age. Within a week they were courting and the ripening of their relationship accelerated when Hughes showed Tamsen an official-looking Decree of Divorce from his wife in mid-December of 1864. It was a clumsy fraud — but Tamsen didn’t know that — with the result that she and Hughes eloped to Pittsburgh, where they were married by the Rev. Dr. Brown on December 20, 1864.

Their marital idyll was brief. Susanna and Thomas Parsons learned of their daughter’s flight almost immediately and Tamsen’s uncle Joseph reached Pittsburgh on the night of the nuptials and contacted the police. The next morning Hughes was arrested in their bridal hotel suite and forthwith indicted for bigamy. Characteristically, he was at first whining and wheedling, then belligerent and defiant. After failing to persuade Tamsen’s parents to drop the charges, he threatened to make “unpleasant disclosures” in court that would forever ruin her character. All of which mattered little: Hughes was soon sentenced to a year in the Allegheny Penitentiary. But, alas for Tamsen, Hughes was pardoned and released only five months later, thanks to the tearful petitions of his long-suffering wife Margaret. Hughes returned to Cleveland in June of 1865 and resumed both his medical practice and his interrupted drinking career.

The events of the next several months would not be unfamiliar to contemporary readers familiar with the ways and wiles of predatory men who stalk vulnerable females. Hughes managed to stay away from Tamsen for the first month after his release and his wife Margaret felt enough confidence about the future to leave with her son for a family visit to the Isle of Man in mid-July. But the cunning Dr. Hughes had only waited to get his inconvenient spouse out of the way. On the night of July 24, 1865 Hughes was discovered in Tamsen’s Bedford bedroom at 2 am by her outraged father Thomas. Armed with a knife and gun, the lovesick Hughes had broken into her bedroom and threatened to kill her unless she gave instant ear to his pleas that she go away with him and become his wife. Still unmindful of the long-suffering Margaret, he promised, “I have a home already furnished nicely for you and will make a lady of you.” Eventually, after Thomas departed to summon the police, Hughes agreed to leave, blustering that he wasn’t afraid and that he was “pretty damned well armed.”

In retrospect, it would become obvious that Hughes was in the grip of a fatal attraction that could have but one outcome. Several hours later, in conversation with a fellow-doctor, Hughes complained that Tamsen had been publicly calling herself “Mrs. Hughes” and he averred that “if that damned bitch doesn’t stop, I’ll shoot her.” The next morning, in front of three witnesses, Hughes commented on a rumor that someone had shot at Tamsen with the words, “It was a pity it hadn’t blown her brains out and saved me the trouble sometime.” That same afternoon, Hughes returned to Bedford, where he told an acquaintance quite plainly that “he must hunt up Tamsen and kill her” if she would not agree to marry him. Meanwhile, Thomas Parsons went to court and filed a suit against Hughes for breaking and entering plus assault and battery as his Bedford house. A few days later, he unwisely withdrew the charges after Hughes posted a bond that he would not further molest Tamsen or her kin. Hughes’ ultimate intentions should have been clear to all from his ominous response to the settlement of Thomas Parsons’ suit:

I thank God this matter is settled. I had made up my mind that I would never go before a court on such charges again. If I went ever again it would be on more serious charges.

The stage was set for the Tamsen Parsons tragedy proper. No one knows exactly when John Hughes’ last bender began. But it was roaring in full force by 8 pm on August 8, when he ran into saloonkeeper Oscar Russell at the St. Nicholas Saloon on Bank St. Several bars and many drinks later, the intoxicated twosome looked up Hughes’ friend Ori (“Bug”) Carr at his Public Square cabstand and enlisted his professional aid in a quest for “girls.” Before leaving on what Hughes coyly described later as this “very unholy mission,” he stopped off at his Ontario St. medical office and fetched a pistol from a trunk.

Several hours later found the unprepossessing threesome at the Franklin House hotel in Bedford, still bereft of female company and roaring drunk. After a few hours of sleep and a quick breakfast of whiskey and like beverages, Hughes directed the compliant Carr’s carriage into downtown Bedford. There on the Plank House Rd., he intercepted Tamsen and her mother on their way back from blackberrying. Hughes alighted and an argument ensued in the street, with the good Doctor accusing Tamsen of bad faith:

You know the promises we have made. You are not going to live up to them, are you . . . ? I have married you, and I am going to live with you, if I swing for it.

It was all the terrified Tamsen could do to simply mutter, “No, I don’t want anything more to do with you.” Finally, a neighbor’s intervention ended the unpleasant interview and Hughes, Russell and Carr went back to downtown Bedford, where they found more alcoholic refreshment in a grocery.

It must have been an afternoon of truly heroic drinking; Russell later testified that they had at least 25 glasses of beer and a “Dutchman” present had to be “laid out” when his stamina proved incommensurate with that of his thirsty peers. But the revels ended abruptly when word arrived that Thomas Parsons had gone to Bedford to get a warrant for Hughes’ arrest. After having Russell pat down his face with flour to disguise the ruddy ravages of his recent excesses, Hughes and Carr departed in the latter’s carriage in pursuit of Tamsen.

Espying her on Columbus St., Hughes leapt from the carriage and accosted her at the front gate of the house next to her own. Once again, he pleaded with her to go away with him as his wife; once more, she answered, “You need not follow me, I will not go.” This time, it seems, he finally got the message. Drawing out his pistol, he said, “Good-bye, Tamsen; we shall meet again across the big waters; half my life is gone and the rest will soon be ended when I have done the deed and paid the penalty. Good-bye, Tamsen.” He then seized her dress with his left hand, placed the pistol to the back of her neck with his right, and fired twice. One of the bullets drilled her spine, just below the base of her brain and penetrated four inches into her skull, the other inflicting a mere flesh wound. Moaning, “Oh, dear!” Tamsen fell to the street and died within moments.

Ignoring the bevy of horrified witnesses converging on the murder scene, Hughes poked his finger in the neck wound and said, “You are a dead girl.” Then he turned on his heel and began walking fast back towards downtown Bedford. Just as an angry mob caught up with him there, Ori Carr’s carriage came wheeling around the corner and Hughes jumped aboard. Putting his pistol to Carr’s head, he ordered him to drive fast.

Ori Carr drove fast but he could not shake the informal horseback posse which soon pursued his carriage, the angry pursuers taking occasional potshots at Carr and his passenger. Finally, just outside Bedford, Hughes jumped off the carriage and took to the woods by the Cleveland & Pittsburgh railroad tracks leading to Newburgh. There, about two hours later, he was discovered hiding in a clump of bushes. Soon hustled back to a Cleveland jail by his captors, the still-sodden Hughes obligingly incriminated himself by insisting to anyone who would listen that he “had a right to shoot her” and that he had “planned the act for two weeks.” Always the gentleman with airs, he grandly offered his pistol as an historic souvenir to one of his captors. Arriving in Cleveland, he enlarged further on his premeditated slaughter, insisting:

I went out there on purpose to killer her, and am glad of it. I killed her out of pure love. If I could have killed Haynes [Tamsen’s uncle], I should feel perfectly satisfied.

The next day’s Plain Dealer expressed the reaction of most Clevelanders to Hughes’ cold-blooded nattering in well-articulated editorial disdain, characterizing his attitude as manifesting “a cool indifference both astonishing and disgusting.”

By the time of his preliminary judicial hearing on August 12, however, the rapidly sobering Hughes had begun to change his story, now insisting that his stalking and shooting of Tamsen was entirely spontaneous:

At the Franklin House Russell did not know that I was going to commit the murder, for I did not know it myself until Miss Parsons passed the carriage; had she not passed by within my sight, I should not have thought of it again.

By the following morning, readers of the Cleveland Herald might have been forgiven if they garnered the impression that it was John Hughes, rather than Tamsen Parsons, who was the unfortunate victim of his “love tragedy.” Hughes was no longer ranting about that “damned bitch” but instead bleating ingratiatingly about the “unhappy girl” he had “hurried into eternity.” Now, he insisted, it was not Dr. John W. Hughes but Demon Alcohol that promoted Tamsen Parsons to a less imperfect world:

The Doctor seemed hurt at the slurs that had been cast on his professional reputation. “Liquor,” he says, “always maddens him, and to the excessive indulgence in that article” he lays the commission of the murder.

No one can converse with him upon the late murder, listen to his cool narration thereof, and his sad tone of voice, and witness his piteous expression of countenance when alluding to the “poor girl,” without being impressed with the fact that this is one of the most remarkable cases in the annals of crime.

A sensible Plain Dealer scribe was having nothing of such bleeding-heart nonsense, and put the murder of Tamsen in the revealing context of other, recent, Cleveland-area crimes against women:

[Hughes’] attempt to palliate the dreadful enormity of his crime by laying its cause to excessive drunkenness, only tends to heighten the disgust in the public mind. We have had enough women murders in cold blood and the perpetrators released on bail of $2,000 or sent to the Penitentiary three years, (such a case is still fresh in the minds of the people); enough, too, of murders such as occurred not long since on our Public Square for the committal of which a penalty, not so severe as is visited upon the thief of $50, was inflicted.

Indicted for first-degree murder, Hughes went on trial in Courtroom #3 of the County Courthouse on Public Square on December 6, 1865. With Judge James Coffinberry presiding, Hughes was prosecuted by Charles W. Palmer and Albert T. Slade, with M. S. Castle, R. E. Knight and William S. Kerruish defending. To say the least, Messieurs. Castle, Knight and Kerruish had their hands full. Given his repeated threats to kill Tamsen and his repeated admissions of malice aforethought after the murder, it sees improbable that anyone could have helped Dr. John Hughes beat the rap. But his lawyers tried hard, spinning defenses of incorrigible dipsomania and hereditary insanity, supported by numerous and verbose medical and character witnesses. But the assertions of hereditary insanity in Hughes family were largely disallowed as mere hearsay by a skeptical Judge Coffinberry, and the testimony of witnesses that they had often seen Dr. Hughes in his cups was of debatable value, as Hughes was such a hardened sot that most witnesses to his prolonged alcoholism admitted that they could never tell just how drunk he was at any given moment.

Arguing for the State, Prosecutor Slade had much more fun. Emphasizing the social and moral gulf between the debauched, much older physician and “an unsophisticated country girl,” Slade hammered Hughes with a litany of his multiple threats to kill Tamsen, some of them even made, apparently, during Hughes’ infrequent occasions of sobriety. Citing clear legal precedents which disallowed Hughes mitigating claims that he was drunk when he pulled the trigger, Slade climaxed his plea for the doctor’s execution with an evocation of Tamsen’s ghost and a command that community sexual standards be upheld by the jury:

The facts cannot be denied. The defendant himself boasted over the ruin he had wrought, “that he should meet the murdered one across the great waters.”

Seems to me even now and here he might see “wandering by, a shadow like an angel, with bright hair, dabbled in blood.”

Gentlemen, we throw upon you the burden of this case . . . I ask you in the name of that community so cruelly outraged, that waits patiently to see whether under any circumstances, the highest penalty can be enforced — I ask you in the name of violated chastity everywhere . . . to this day mark by your verdict your estimate of the protection which shall be given to the poor man’s child.

Slade’s oratory was a hard act to follow but R. E. Knight did his best for Hughes. Comparing Hughes’ “love mania” to the historic infatuations suffered by King Midas, Peter the Hermit, Mark Antony, Henry VIII, and Troy’s Paris, Knight argued that the combination of Hughes’ chronic alcoholism and hereditary instability made his violent act inevitable:

He loved her madly and blindly, and, when he found the object of that love forsake him and turn away from him, the awful passion of love was disappointed, and he, under the influence of disappointment, became insane, and when that fearful cloud and paroxysm crossed his mind his intellect became eclipsed and, failing in self-control and judgment, perpetrated the fearful deed.

It only remained for Knight’s fellow counsel, M. S. Castle — with a tactic not unfamiliar to observers of contemporary crimes of violence against women — to try to blacken the name of the victim by way of mitigating his client’s crime. Tamsen, Knight argued, was no “mere child” but a “person come to responsible womanhood,” who had reciprocated Hughes’ passion with full knowledge that he was wed to another. And, ingeniously, Knight insisted, the fact that Hughes had so thoroughly implicated himself before the fact — with his multiple threats to kill Tamsen — was actually evidence that he could not have premeditated the deed:

It is inconceivable that, if he meditated her murder, or desired to take her life, he should thus drum up witnesses of the contemplated deed, and so plan things as to make his conviction fatally sure.

The jury wasn’t fooled by Knight’s contrarian reasoning: on December 22, after only two hours of deliberation, it returned with a verdict of Guilty of Murder in the First Degree. Sentenced to death by Judge Coffinberry on December 30, Hughes whined anew that the devil must have made him do it, as “it is contrary to my nature to be cruel” and that his only failing with Tamsen was that “he loved her too well.”

Given his personal history of unceasingly shameless behavior, it should come as no surprise that John Hughes’ last days were marked by the same defects of character and excesses of rhetorical insincerity that had hitherto characterized his life. As is so often the case with condemned prisoners, he quickly got religion and was soon boasting to a Plain Dealer reporter about the “serene state of mind” ensuing from the “influences of the religious regime which has been the main feature of his prison life.” Granted liberties denied to his fellow County Jail prisoners, Hughes was permitted to entertain a daily deluge of visitors, mainly sympathetic females, whom he regaled with a farrago of pious and edifying sentiments. Some of these impressionable females soon got up a petition to the Governor begging the commutation of his death sentence, which eventually gained the signatures of some surprisingly prominent citizens.

Naturally, Hughes’ dramatic moral reformation while on Cleveland’s death row sparked a personal and heartfelt reevaluation of the death penalty. Although he had indicated a willingness to be lynched in Bedford when captured on August 9th, he now emerged as an eloquent, indeed poetic adversary of capital punishment. On January 29, 1866, the Plain Dealer printed his doggerel riposte to a Cleveland Leader editorial applauding his sentence:

The Leader of a class, a man to kill,

Quotes Bible proof, swears by the “poet Will.”

Trite wisdom, man’s law of God by Moses,

‘Tis obsolete–who, to-day supposes

Adultery, Sabbath-breaking, the breath

Of sland’rers, each and all, “be stoned to death.”

The same for other scores–economy

In time compels. See Deuteronomy.

Did Jesus say so ‘mid the crowd’s uproar?

No! Saint throw first,” “Go, woman sin no more.”

Once embarked upon his path of moral rearmament, John W. Hughes was not likely to stop with mere condemnation of the death penalty. The poetic habit, like writing Letters to the Editor, is a vicious and addictive habit, and subsequent editions of Cleveland newspapers featured the good Doctor’s rhymes on his adopted city and the evils of intemperance. His verses on drink are best charitably ignored — he blamed his fate solely on the imbibing of adulterated beverages — but his verses on the Forest City spoke well for the literary discipline of a muse no doubt distracted by impending doom:

Scarce three score years and ten, since Indian trail

Was followed safe thro’ woods and down the vale

Where now canal and river run to hide

Commingled waters in Old Erie’s tide.

Where red men chased the flying deer in sport

Is now a finished town, a thriving port.

Wealth, commerce, enterprise combined to make

Cuyahoga’s Forest City of the Lake.

Whose public buildings, churches, schools are classed

Equal in architecture, unsurpassed

By any place for — homes in pretty lots —

Palatial mansions grand, with cozy cots —

In shaded streets, from Kinsman to St. Clair —

Ohio City — Willson to the Square:

The avenue–with suburbs round to Bank,

We find abodes well suited to each rank;

While style and fashion, etiquette, bon-ton

Are set to Euclid’s rules. They can’t be wrong,

Ability and talent — beauty, where

To Cleveland’s sons and daughters can compare?

Associations, learn’d, unceasing lend

Instructive aid in literature to bend

Its youth to purity of mind and heart

To will: from which they never should depart.

Space prevents inclusion of the rest of Hughes’ strophes on Cleveland but the evidence is clear to even the meanest understanding that had events been more fortunate, he might well have lived to be revered as the poet laureate of his adopted town.

The day after his Cleveland verses saw print, Hughes received word that Ohio Governor Jacob Cox had refused to commute his death sentence. On February 5th, he retaliated with the public release of two characteristic documents. One was his requested epitaph, rendered in his usual style and showcasing his by now habitual themes:

A life for a life! no less;

‘Tis Law! tho’ in phrenzy done.

Pause! beware of drunkenness

I’m a victim! are you one?

In the strength of manhood’s prime

Sternest Justice scaled my doomed,

Mournful penalty for crime,

A shameful death, a convict’s tomb.

Hughes’ other effusion was a letter to his wife, Margaret, in which he again fulsomely exhibited the monstrous combination of braggadocio and self-pity that had informed his life. Even in the shadow of his gallows, the boastful Hughes couldn’t suppress his pride in the leading figure he had cut on a Cleveland stage:

I have already sent you the whole particulars of my trial. By all accounts there never was a trial in this section of the country that created so much excitement and interest as my unfortunate one did. The whole community was moved. Crowds attended the whole proceedings; and, indeed, it required (as the papers called me) a man of iron to bear the staring of the crowd.

John Hughes’ public bravado was his usual playacting sham. He much feared his impending fate, and on the night of February 7th, 1866, he took an enormous overdose of morphine, which had been smuggled into his jail cell by some sympathetic party. But Sheriff Felix Nicola, a shrewd lawman, soon diagnosed his prisoner’s malady and restored him to consciousness by the time-honored method of forcing him to walk back and forth in his cell for some hours. Meanwhile, tickets to his hanging were distributed, a photograph of Hughes was taken in his cell by the aid of chemical lights, and a scaffold brought up from Summit County — the same gallows employed for the taking-off of James Parks et al. — and erected in the west corridor of the County Jail. Under Sheriff Nicola’s direction, carpenter Thomas Craig modified the structure to bring it in line with his conception of an efficient death instrument.

February 9 arrived at last, and Hughes spent his final hours bidding adieu to his fellow prisoners and consulting with his spiritual advisor, Dr. J. A. Thome of Oberlin College. His farewells to his fellow felons brought out that delightful streak of sanctimony that had ever marked his personality, replete with pious adjurations that would have done honor to Dickens’ canting William Dorrit at his pompous worst: “Cleanliness is next to Godliness” and “Keep yourself in better trim.”

John W. Hughes died pretty game, albeit with his habitual loquacity. Permitted to speak on the scaffold, he harangued the assembled crowd for sixteen minutes, his text, not surprisingly, harping on the inequities of capital punishment. Accusing the Old Testament prophet Moses of being “the greatest murderer we ever heard of” for instituting capital punishment in the matter of the Golden Calf, the new-born Scriptural scholar attacked the deterrent rationale of capital punishment:

The death penalty is ridiculous, and if you consider over it you find it is wrong.

One life is as good as another. What advantage is it to take my life? None!

It is not an example to deter others from the crime. Did I remember pointing the pistol? No, I don’t remember it to this hour.

Hughes went on to deny the divinity of Christ and to express his earnest wish that his unjust death might serve as a powerful argument against the death penalty. Showboating to the last, he now stepped to the trap and, removing his collar, threw it to the crowd below. His hands were manacled and his arms and legs pinioned. Just before the black cap came down over his head, he declaimed, “O grave, where is thy victory? Oh death, where is thy sting?” Smiling, it is said, as the rope was placed around his neck, he hurtled through the 74-inch drop to eternity at exactly l:07 pm. Not a muscle or limb was seen to twitch and it was determined that he died instantly from a broken neck. Twenty-six minutes later, he was cut down, placed in an imitation rosewood coffin and discharged to a committee of Manxmen for burial.

Of course Hughes, being Hughes, had to have the last word. Just before mounting the scaffold, he withdrew his previous epitaph and substituted the following verse:

Lo, wavering hope,

Bearing life on its fluttering wing,

Heralds the sad note death to bring.

In mystery grope for fraternity

The Grave when the unseen hand

Leads on to the Spirit land,

With soul to elope

Thro’ Eternity.

In simple fairness to the shade of the girl he murdered, it is only just to allow the last word in the Parsons tragedy to a discerning moralist on the staff of the Cleveland Herald. From the start, this unknown scribe had taken a jaundiced view of Hughes’ pretensions, prevarications and pomposities and now responded to his last public utterances with fine and measured scorn. After abusing other Cleveland journals for allowing misplaced sympathies for the erring Doctor to invade their columns (“But Hughes was ‘so interesting,’ could ‘talk so beautifully,’ was ‘so penitent,'”) the Herald scribe rendered a final, pitiless judgment of the shameless Doctor John W. Hughes:

Although his deportment and general bearing has been such that no material exceptions could be taken by those who have casually called on him, or by those who have been most intimately associated with him in prison, it was evident to all who took the trouble to think for a moment that there has underlain all his motives and actions a disposition to court notoriety, and that, with all his acknowledged education and talents, there was an evident want of the finer sensibilities and a lack of the better moral perceptions. He was continually striving to make himself and his horrible surroundings as conspicuous as possible.

So ended the melancholy saga of Dr. Hughes and Tamsen Parsons. Readers desiring a more detailed account of this vintage Cleveland-area crime should consult the author’s more lengthy narrative in The Corpse in the Cellar (Cleveland, OH: Gray & Co., 1999) or Albert Borowitz’s excellent account, “The Fatal Charm of Tamzen Parsons,” (Western Reserve Magazine, Vol. 35, 1989).