Main Body

IV. Bloody Doings at Olmsted: The Lonesome Death of Rosa Colvin (1866)

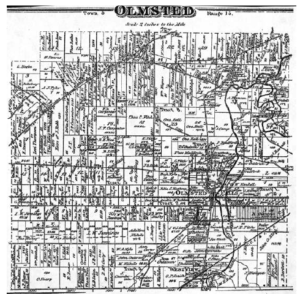

In the current megalopolis that is today’s Cleveland, it is difficult to grasp that the city was not always the physical core and psychological cynosure of Cuyahoga County. Indeed, the first five murderers executed in the city did not commit their crimes there, but rather in the outlying, largely rural and even wilderness townships. Olmsted Township was just such a wilderness area in 1866, and the terrible crime Alexander McConnell committed there affords an illuminating picture of the harsh lives and crude living conditions endured by the tough pioneers who lived beyond the relative sophistication of the Forest’s City’s muddy avenues and ramshackle commercial blocks.

William Colvin and his wife Rosa would not have been mistaken for one of Cleveland’s First Families in any era. Arriving in the Western Reserve sometime in the mid-1860’s, the Scotch-born Colvin and his American wife scratched out an uncertain existence in the wooded and sparsely-inhabited area just southwest of the village of Olmsted Falls. The unskilled William, known to his neighbors as “Stuttering Bill,” generally labored as a woodcutter or quarryman in the area, while Rosa kept house, such as it was, in a cabin in the woods, about three miles west of the Village. And it wasn’t much: situated in a small clearing surrounded by a thousand acres of forest, the Colvin manse was variously described by contemporary observers as either a “hovel” or “shanty.” Or as one disgusted Cleveland Leader scribe limned the Colvins’ domestic scene:

There was no hint of yard or garden. The open area was inexpressibly dreary, and the house seemed the picture of all that is wretched, dismal and profane in life. But no conception of the squalor could be formed until the interior was inspected. There were but two rooms, lighted by one common and two very small-sized windows. No more were needed, since daylight flooded the house through the wide cracks between the upright boards. The floor was loose and full of fissures and chasms. In the front room were a bed, table, a broken cooking stove, two or three chairs, a cupboard in which were dirty dishes, bread and crackers, besides several barrels, boxes, etc. A few comic pictures were pinned like a naturalist’s insects to the siding. In the back room were two bunks, a box stove, and trumpery ad infinitum.

Of course, the reporter’s impressions may have been prejudiced by the fact that almost everything he saw in the cabin was covered with blood — but let us not get ahead of our story.

The spring of 1866 found the Colvins living in imperfect amicability in the aforesaid woodland bower. When not working as a cordwood cutter for nearby landowner Robert Crawford, William Colvin cultivated local repute as a thick-witted, surly fellow, given to excessive drink and the physical abuse of his wife. Several of their perspicacious neighbors would later testify at Rosa’s inquest that they had witnessed “Stuttering Bill” strike his wife and others would recall seeing the marks of domestic violence on her face. Not that said neighbors had much sympathy for Rosa: she had married Bill about a year before and it was whispered that the twenty-eight-year old woman had been married twice before she sought lawful union with the unprepossessing Colvin. (The only certain facts ever proven about Rosa’s past was that she was the mother of a previously deceased child, beside whom Rosa would be eventually be laid to rest in a Berea grave). All of which would be remembered with lip-smacking relish, when reports of ill-doings at the Colvin cabin electrified the talkative citizens of northeast Ohio.

The first link in the chain of Rosa Colvin’s doom was forged with the arrival of thirty-five-year-old Alexander McConnell in Olmsted Township at the beginning of March, 1866. Originally hailing from County Tyrone in Ireland, the illiterate McConnell had emigrated to Canada in 1850. Settling in the town of Fitzroy, near Ottawa, McConnell married a widow with six children there, sired three more of his own and prosecuted general farming without great success. But that prosaic life ended in the mid-1860’s, when he was forced to flee to the United States after fracturing a man’s skull in a dispute over a horse sale. The spring of 1866 found him drifting down from Buffalo to Olmsted Township, where he secured temporary work cutting wood for Robert Crawford. And it suited both the convenience of McConnell and Crawford for the Canadian to board with the Colvins in their sylvan home, close as it was to the Crawford woodlots. A thickset man, McConnell was about 5’5″, with light gray eyes, dark, sandy whiskers, brown hair and a low brow. A possibly biased observer characterized his demeanor thus in the pages of the Cleveland Leader — on the day after he was hanged:

[McConnell’s eyes] are restless and sinister in their expression. When conversing he never looks you in the face; his lips wear a continual smirk and the corners of his mouth twitch nervously.

Be that as it may, McConnell seemed to get along with his hosts; in the shadow of the scaffold he would recall the pleasure he took in helping them with household chores. Saturday, March 24 dawned cold and clear. William and Alexander arose at 7 am, consumed a simple breakfast, and set out on foot for Berea. Both of them were intent on finding quarry work there, and McConnell hoped to arrange continued board at a house Colvin planned to rent there. But after only a quarter mile, near the Cleveland & Toledo railroad tracks, McConnell turned back, telling Colvin that his knee was hurting badly and that he was going to return home. Colvin continued on to Berea. Whether he concluded his intended business is unknown — but it is certain that he soon fell in there with a slow-witted acquaintance named Joe Miller, and that he and Miller spent the latter part of the day boozing it up at various drinking establishments in southwest Cuyahoga County.

Meanwhile, McConnell returned to the Colvin cabin. Picking up some of William’s clothes (including an overcoat, a pair of fine boots, a pair of quarry boots and a “pair of French gray pants”), Colvin put them under his arm and replaced them with his own shabby clothing. Then he broke open one of Colvin’s trunks, abstracted several hundred dollars in bounty money Colvin had earned through various enlistments in the Union Army, and took his leave. Affairs had not prospered well for McConnell during his American sojourn and he was determined to get back to Canada by whatever means necessary.

Not far from the cabin, however, he soon met Rosa Colvin in a lot owned by a man named Engler. She had learned that McConnell had returned to the cabin, become suspicious, and gone in search of him. Seeing her husband’s clothing in McConnell’s possession, Rosa demanded to know what the hell was going on. There was no problem, cooed McConnell, it was just that William had decided to stay in Berea and had sent McConnell back to fetch some of his clothing. Very well, replied the dubious Rosa, then I will go with you. No, riposted the increasingly frightened McConnell, your husband said he won’t stay there if you come. The upshot of their tense dialogue was that they both returned to the Colvin cabin, probably about 11 am that morning. There, Rosa soon found the rifled trunk and confirmed her original suspicions that McConnell intended to rob them and flee.

The only account we possess for what followed is McConnell’s confession, but its details fit pretty well with the physical evidence of the murder. Seizing a poker, Rosa blocked the cabin door and told McConnell he wasn’t leaving until her husband got home. As he tried to brush by her, she hit him on the arm with the poker. McConnell knocked her down with his fist but she got up and hit him with the poker again. So he hit her with a stick of firewood — and she hit him with the poker again. The enraged McConnell had had enough of this: grabbing an ax he hit Rosa in the middle of her forehead, killing her instantly. And the subsequent condition of the cabin supported McConnell’s scenario: there was blood everywhere, giving unmistakable evidence that Rosa Colvin had put up an almost super-human fight before falling before her murderer’s ax. The fatal struggle had taken about 15 minutes.

It must have been a terrible scene that followed in that crimson-drenched shanty. McConnell later said that he just held Rosa’s body for 20 or 30 minutes after his decisive blow, unable to believe that he had actually killed her. Then, coming to his senses, he soaked up some of the blood with a quilt and, wrapping Rosa’s bloody body in a dress, carried it out of the cabin. At a woodpile about 430 feet away, he laid the corpse on the ground, covering it with the quilt and some loose pieces of wood. Then he fled, walking rapidly towards Elyria with two carpet sacks containing Colvin’s clothes and money. From there he took a train to Sandusky, walked from there to Clyde and from Clyde to Fremont. From Fremont he took the train to Detroit, crossed over to Windsor and arrived back at his home in Fitzroy on Thursday, March 29, five days after Rosa Colvin’s murder.

The simple brutality of the murder contrasted bizarrely with the Byzantine confusion that followed its discovery. William Colvin and Joe Miller returned to the Colvin hovel about 8 pm that evening. It was already dark, a heavy snow was falling and it is likely that Messrs. Colvin and Miller were feeling no pain from the day’s copious libations. How else to explain that when they returned to the blood-spattered cabin neither of them noticed anything untoward at the scene. True, Miller later remembered that he had remarked on a broken window with a blood-stain on it and the absence of Colvin’s better half. But “Stuttering Bill” took it all in stride, merely remarking that Rosa must have “skedaddled” with his Canadian boarder.

Colvin’s obtuse obliviousness continued into the next morning. Arising early, he and Miller were still enjoying their breakfast about 9 am, when a visit by Colvin’s employer Robert Crawford and his brother James spoiled their quiet morning. Shocked by the blood all over the place — there were generous pools of it on the floor and a mop head standing in a corner was stiff with encrusted gore — the Crawfords must have been further amazed by Colvin and Miller’s assurances that they had not noticed the blood the previous night or when they arose in the morning. Nor, too, had they apparently noticed one of Rosa’s bracelets and an earring on the floor, both of them caked with blood. Calling in neighbors to keep an eye on Colvin and Miller, Robert Crawford went to Olmsted Village for Constable Sabin. By nightfall, both Colvin and Miller were in jail, awaiting the outcome of the scheduled inquest on Monday morning.

Owing to the incredible demeanor of Colvin and Miller, the initial theory of the authorities was that Colvin, with or without the aid of Miller, had murdered his wife and hidden the body. The fact that his boarder McConnell, too, was missing inspired the further supposition that a jealous William had caught Alexander and Rosa in flagrente-something at the shanty and slain them together. And Colvin’s claim that his clothes and money were missing hardly argued for his innocence: everyone who saw the inarticulate Colvin that day noticed that he seemed more concerned about his missing clothes than the whereabouts or fate of his wife. And of course, he would say that he had been robbed, then as now, a convenient and all-too-transparent lie to cover a purely domestic killing. No one believed Colvin’s assertion that the blood on his vest came from some freshly-slaughtered beeves he had hauled on the day before the murder. And Joe Miller, a near-idiot, would not have helped anyone with his testimony, much less an unsympathetic, wife-beating, loutish sot such as William Colvin.

The discovery of Rosa’s body on Sunday afternoon didn’t improve the prisoners’ prospects. Several hours of searching through the surrounding, snow-covered woods ended when a searcher’s bootheel snagged on a bloody dress near the woodpile. Found next to the woodpile, Rosa’s corpse was covered with snow, indicating that she had been killed some time before 6 pm on Saturday. She was a horrible sight: her clothes were pulled up over her chest, her left arm thrown up to her cheek, her hair disheveled and clotted with blood, the top of her left ear cut off and she sported a large triangular wound in the middle of her forehead, shaped exactly like an ax-head. The discovery of his wife’s body just a few hundred feet away from his cabin did not help Colvin’s case, and few were surprised when the inquest ended on March 27 with the arraignment of the two suspects on a murder charge. Given local prejudice, however, it is probable that Colvin and Miller would have been held on far less evidence. Such prejudice was well-expressed by Cleveland journalists, one of whom characterized Miller as “a pumpkiny-looking youth with fuzz on his face and apparently, a brain of mush,” who sat stupefied before his accusers like “a piece of pig metal.” The same scribe reserved even greater scorn for Colvin, whose supposed villainy he limned in columns that might have shocked the late Sam Sheppard:

Colvin is a Scotchman and about forty years old. [He was actually 33]. He has a swarthy complexion and looks like a black snake. The eye is impenetrable and perfectly devilish. And this suits his nature. He is an essential brute, and has treated his murdered wife, whom he married a year ago, as only a fiend could, kicking and pounding her and threatening to take her life. He seems capable of committing any crime.

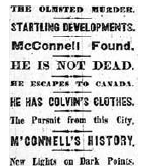

Fortunately for Colvin and Miller, there were several lawmen unswayed by popular prejudice. One was Cuyahoga County Sheriff Felix Nicola and the other was a detective named John Odell. From the beginning, they suspected that the missing McConnell was the guilty party and, after consultation with County Prosecutor M. S. Castle and County Commissioner Randall Crawford, they began looking for him even before the inquest ended on March 27. Acting on a tip concerning the fugitive’s original home, Odell arrived in Ottawa on Thursday, March 29. Securing a posse of Canadian detectives, Odell and his men knocked on Colvin’s door in Fitzroy at 5 am the next morning. His wife Ann answered the door and told the inquisitive officers that her husband was absent. It was obvious the worried woman was lying and Odell’s men began to search the house. As one of them mounted a ladder to a loft, McConnell, who was hiding above, hit him with a stick. Despite his protestations of innocence and repeated threats that he would be shot, McConnell refused to surrender himself until Odell’s men began removing the floor beneath him. Taken back to Cleveland, he was arraigned and quickly indicted on a charge of first-degree murder. Released from jail, an estatic William Colvin shed tears of joy, a reaction noticeably lacking, censorious types noted, in his response to his wife’s slaughter.

Opening on June 22, 1866, McConnell’s trial consumed a week and was a cut and dried affair. With Judge Horace Foote presiding, McConnell was prosecuted by M. S. Castle and A. T. Slade and defended by C. W. Palmer and R. E. Knight. (It was an oddity remarked by all that these four lawyers reversed the roles they had played in the recent trial of John W. Hughes). Not that it mattered much: McConnell had been captured with the stolen clothes and much of the missing money in his possession. Not taking the stand in his own defense, he appeared emotionless and completely unmoved throughout his trial. Aside from vigorous cross-examination of the State’s witnesses by Knight and Palmer, the only words offered in his defense were some depositions by Canadian character witnesses. Retiring on the evening of June 28, McConnell’s jury returned a verdict of Guilty of Murder in the First Degree the next morning. Twenty-four hours later Judge Foote dismissed defense counsel’s motion for a new trial without even bothering to listen to the State’s brief, and pronounced sentence with these words:

You have had a fair, patient and impartial trail and you have no one to blame for the result but yourself, and no reasonable regrets therefore, save from your own misconduct. I abure you to prepare to meet the result of your trial, which I now announce to you. It is the sentence of the law that you, Alexander McConnell, be taken from this place to the jail of this county, that you be therein kept in close custody by the Sheriff thereof, until the 10th day of August, A. D., 1866, and that between the hours of 10 o’clock in the forenoon, and 2 o’clock of the afternoon of said day, you be hung by the neck until you be dead, and may God have mercy on your soul.

McConnell received his sentence with his habitual passivity. Offered an opportunity to make a statement, he remained silent. Upon meeting his distraught sister outside the courtroom, however, he betrayed some uneasiness. Perhaps it was the knowledge that she had utterly impoverished herself, as did the rest of his family, to finance his hopeless defense. Courtroom buffs noted that the sentencing of the reliably histrionic Dr. Hughes had drawn a far larger crowd that of the stolid McConnell.

As Dr. Johnson might have predicted (“Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully”), Alexander McConnell’s disposition began to thaw and improve as his date with the scaffold drew nearer. Initially angry and bitter at the verdict, he fulminated death threats against his captors, especially Sheriff Nicola, and plotted an escape from the County Jail. He almost made it: in late July, he and some other prisoners succeeded in blowing an adjoining cell lock off with some smuggled powder but were caught while trying to blast another hole through the jail roof.

After that, McConnell seemed to resign himself to his fate, or as he put it to a number of those with whom he conversed in his final days:

It is useless to tremble at my fate; it must come and when it does come I will try to die like a man hoping Heaven will be merciful — for I deserve the Halter.

He began reading the Bible (he could read a little but could not write) and several weeks before his execution, on July 11, 1866, he dictated a full confession of his awful act in the presence of Sheriff Nicola, Prosecutor Castle, three of his jurymen and two newspaper reporters. Averring that he never meant to harm Rosa, who had always treated him kindly, he swore that he only slew her because she barred his escape from the shanty. As for his flight to Canada, he admitted that he never thought he would be pursued there by lawmen; indeed, when Odell’s posse came knocking on his door in Fitzroy he assumed they were bailiffs come to arrest him for a $12 debt. And he insisted that he had never taken any money from the cabin. Always the equivocator, though, McConnell also hinted in some of his last conversations that William Colvin had once solicited him to help him get Rosa “out of the way” so Colvin could go away to Canada with McConnell. McConnell’s version of this improbable conversation ended with him piously responding, “I know what you mean, Colvin, but I would never do such a thing.” After McConnell’s execution, a kindred story was related by one Henry Bislick. Bislick, who lived near the Colvins, claimed that he came upon William three days before the murder. There was a sixteen-year-old girl with Bislick, and Colvin said to him, “I’m going to marry this girl, as my wife will be dead in a day or two.” When Bislick remonstrated that Rosa was still alive, Colvin allegedly replied, “I know that, but she’s going to die in a day or two.”

A small crowd of lawmen, invited spectators and several newspaper reporters turned out for McConnell’s hanging in the Cuyahoga County Jail on August 10. Early that morning, McConnell met with William Colvin for the last time. Asking his forgiveness, he begged Colvin to shake his hand. Colvin refused, muttering “If God forgives you, I do,” but he finally grudgingly clasped McConnell’s hands when the latter fell to his knees in prayer and burst into tears. Then, after a final chat with his religious counselors the Rev. Bush of the Methodist church in Berea and an Episcopalian minister, the Rev. Lathrop Cooley (who would make a career of ministering to the Cuyahoga County condemned), McDonnell was led to the scaffold — the same used for James Parks, Dr. Hughes and various other felons — at 12:18 pm by Sheriff Nicola and his deputies. Deciding not to make an extended gallows oration, McConnell merely murmured, “I am ready to go — the sentence is just.” His arms and legs were pinioned, the black cap put over his head and the rope, a custom-made one-inch halter which had already proved its mettle on Dr. Hughes, adjusted around his neck. Just before Sheriff Nicola sprang the trap, McConnell turned towards his executioners and said, “Gentlemen, I trust in the Lord. I hope all men and women will forgive me. I forgive all and hope to be done by the same. Goodbye.” Then, turning to the press box, he said, “Good bye — this is a dreadful hour.”

He didn’t know the half of it. A second later, Nicola triggered the drop and McConnell fell through it. Apparently, McConnell turned his head slightly to the left a split-second before the drop opened. His movement allowed the rope to slip up under his chin just enough so that, instead of breaking his neck, Alexander McConnell began strangling in agony before the horrified spectators. Hanging buffs present concluded that McConnell’s discomfiture was probably just an unfortunate combination of circumstances caused by the combination of his thick neck and light (140 lbs.) weight. The next day’s newspapers noted that he was nonetheless pronounced dead after 14 minutes and that his body was taken down after a half hour. What actually happened was not reported until it leaked out twenty-three years later in a Plain Dealer Sunday feature on Cuyahoga County hangings:

When the trap was sprung the noose slipped, the knot passed under his chin, he writhed for some minutes and strangled, the hangman [Sheriff Nicola] hastening the result by letting himself down by the rope until he stood on McConnell’s shoulders, his weight drawing the noose tighter.

That, presumably, was the end of Alexander McConnell and the terrible Olmsted murder. One likes to think, however, that its enduring residue might be one still-haunted corner of Olmsted Township, about three miles southwest of Olmsted Falls. There was some feeling in the wake of the murder that the Colvin shanty be burned, one journalist insisting, in his call for vigilante arson, that it had been “the abode of free fighters, prostitutes and murderers” even before Alexander McConnell made it notorious. But the Colvin murder cabin was still standing six months later, now inhabited by a family named Miller. Preserving the high standards of Colvin housekeeping, the house was still marked with the stains of dried blood, with even some of Rosa’s bloody handprints adorning the walls. Miller and his family also reported much poltergeist phenomena troubling the house at night: beds shaking, the sound of an ax chopping in the back room and the chairs, doors and windows in violent commotion. The author knows not the precise location of the Colvin murder cabin but there are no doubt inquiring minds who might take up this matter.