Main Body

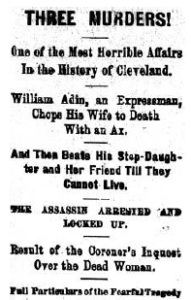

VIII. “I am Settling For All Past Wrong. . .”: William Adin’s Cross-Town Bloodbath (1875)

The narratives of each of the nine Cuyahoga County executions reveal features, motives and personalities unique to each murderer and the circumstances of his judicial killing. John O’Mic was the youngest victim, and his taking off was the most lugubriously macabre. James Parks’ murder-by-decapitation was a crime of exceptional brutality and his extended sojourn on Cleveland’s Death Row by far the longest, thanks to legal technicalities that would make F. Lee Bailey proud. The crime of Dr. John Hughes was Cuyahoga County’s first capital atrocity committed in the name of “love,” and the person of the Doctor himself constituted a villain of singular and almost demonic vanity. The hanging of Alexander McConnell was certainly, if unintentionally the most painful execution, and all the more regrettable because he may have been the only one of the nine condemned who truly repented of his black deed. The civic cesspool exposed by the denounement of the Skinner murder case and the execution of Lewis Davis was, from first to last, an unprecedented public morality play that soiled everyone involved in it on both sides of the law. John Cooper’s spectacular violence against James Swing was an early instance of “black-on-black” Cleveland crime and was also remarkable for resulting in the shortest capital trial ever held in Cleveland. (Although no one knows how long it took to convict O’Mic, it probably didn’t take very long). Stephen Hood’s cold-blooded slaughter of his stepson set new standards for stony-heartedness and unrelenting mendacity. And Charlie McGill, the last of the nine men executed, gave the good Dr. Hughes — as we shall record anon — stiff competition in the category of the ultra-stylish crime passionel. But for sheer cussedness, mayhem and gore galore, there is nothing to beat William Adin’s triple murder bloodbath on December 4, 1875.

79Bill Adin’s last day as a free man began in typical, even mundane fashion. Rising at 4 am in his bedroom in his house on the “Heights” (as the Tremont neighborhood was then called), the 56-year-old expressman (he made his living delivering packages for Cleveland firms) dressed quietly, went downstairs to the kitchen and lit a fire. Thinking it too early to wake his wife, Barbara, the short-statured, bewhiskered Yorkshireman walked 75 feet down the street to Engine House #8 of the Cleveland Fire Department. There he chatted for about an hour with fireman Otto Schuardt. Schuardt had talked many times with Adin of late, and he knew the direction the conversation would take the moment Adin walked in the door. It started out with an innocuous remark about a recent fire but almost immediately veered into Adin’s favorite topic: his family troubles. This was a whiny monologue Schuardt had heard before–as had everyone who knew the sociable, talkative Adin. Indeed, his alleged family troubles were well known all over Cleveland.

No one knows when they started and how much of them were real or imagined. But it was no secret that William Adin was a deeply unhappy man at the end of 1875, and he poured out the familiar litany of his woes over the next hour. His wife was stealing from him, he told Schuardt, and his stepdaughter Hattie was robbing him, too. He’d caught them both and it was all Hattie’s fault for poisoning her mother’s mind against him and getting her to steal the money for her own benefit. Now the two of them were trying to get him to sign his property over to them, the house-grocery store structure where he lived and ran his business at the corner of Scranton and Starkweather. They’d been stealing from him for years, he thundered to Schuardt, and now he didn’t even have the money to pay the interest on his bank loan or his County tax bill. And now that streetwalker Hattie was living with that no-good friend of hers, Mrs. George Benton, in that house of ill fame on Forest St. (East 37th St., near Central Ave.). He’d put up with it for years, Bill Adin shouted, and he wasn’t going to stand for it any more. He was going to have a “settlement for all past wrongs,” by God, and he “might just as well settle first as last” and he believed in fact, “that he would settle with her right now–this morning!” So Adin ranted on for over an hour in this fashion about his wife and stepdaughter. Then, hearing the station clock strike, he asked fireman Peter Cary what time it was. Told it was 6 am, he departed for home. Schuardt thought no more about the conversation after Adin left. He and everyone who knew Adin had heard it all before, and he supposed that Adin was talking about a financial “settlement.”

Just how good-natured, industrious, thrifty William Adin had come to such a pass will never really be known. Born in Barnsley Commons, Yorkshire on February 17, 1819, Adin had grown up in a family of modest means with eight children. Leaving home at six, he had enjoyed but three days of schooling and from the age of 16 walked with a limp after being kicked by a horse. That accident didn’t seem to affect his disposition or work ethic, however, and he labored at various manual occupations around Yorkshire before emigrating to Cleveland in 1852. During the next few years he pursued various careers, including farming, coal mining and a stint as a steward on a Great Lakes ship. In 1858, he married Barbara McKay, a widow his own age and they worked together for some years at a downtown peanut stand on Superior Ave., along with Barbara’s daughter by her first marriage, Hattie McKay. In the early 1860’s, Adin began working as an expressman with his own horse and wagon. Over the next few years he built up a solid and lucrative business, developing a reputation as a reliable, industrious worker and doing delivery work for such reputable Cleveland firms as Cobb, Andrews & Co. and Brooks, Schinkel & Co. By the late 1860’s, Adin had prospered enough to build a house on the “Heights,” with a room for Barbara to run as a neighborhood grocery and Hattie helping out behind the counter. Everything seemed grand, Bill Adin’s property was worth an impressive $6,000 and he doted enough on Hattie to yield to her plea to send her to a good commercial college.

Somehow it all went wrong in the early 1870’s. Maybe it was mental illness, maybe it was a mid-life crisis, maybe it was, as the old murder indictments used to read, “at the instigation of the devil.” But sometime about the same period that his stepdaughter Hattie McKay turned into a beautiful and personable young woman, affable Bill Adin’s disposition went sour. There is no evidence to support his fanatical conviction, repeated until he fell through the hangman’s drop, that his wife and Hattie had orchestrated a plot to steal everything he had and dispossess him of his property. But there is no question that he believed it by 1874, and by that time he was roaring and ranting his wild accusations against his wife and stepdaughter throughout the length and breadth of Cleveland. There may have been something darker, too, involved in William Adin’s change of attitude towards his 23-year-old stepdaughter: Hattie McKay told at least one person that he had unsuccessfully tried to “ruin” her several times. He also didn’t like her independence: he tried to get her fired from her sales job at the J. R. Shipherd millinery store, telling Shipherd that his stepdaughter was a prostitute and common thief and demanding that Shipherd fire her. Meanwhile, he stepped up his abuse of Barbara, threatening her with physical harm and telling everyone he met that she stole money out of his pants while he was asleep at night. Both Hattie and her mother had taken enough abuse by the autumn of 1874. On the night of December 3, after a violent quarrel which climaxed when Adin smashed down the ill and bedridden Barbara’s bedroom door with an ax and threatened to kill them, Barbara and Hattie fled the house with two trunks of their belongings. Taken into the Forest Ave. (East 37th St.) home of one of Hattie’s sympathetic friends, a Mrs. Elizabeth Benton, Hattie commenced a completely independent life and Barbara filed for divorce on December 14.

Alas, it was not to be. Barbara was granted temporary alimony and eventually won a supplementary lawsuit for recovery of her possessions from the house. But in the end, it was the old familiar, sad domestic story: William the husband cried, William the spouse pleaded and William Adin the contrite helpmate promised he would turn over a new leaf and be good, if only sweet Barbara would come back to him and drop her divorce suit. Which she did, in the spring of 1875, returning alone to face his eventual and inevitable wrath alone, as her more sensible daughter refused to leave Mrs. Benton’s welcoming refuge. Shortly after her return, Adin ran into Justice of the Peace E. W. Goddard, who had presided over the disposition of their domestic legal troubles. When Goddard congratulated Adin on his reconciliation with Barbara, Adin launched into a passionate repetition of his grievances and swore that he would “pay her back for it.”

William Adin got home from his firehouse colloquy shortly after 6 am on December 4. Barbara had prepared breakfast and the food was on the table when they resumed a quarrel waged the night before. It followed the usual text: William asked her for money to pay the taxes, Barbara said she had none, and he launched into his usual litany of threats and accusations. Things got nastier and nastier until finally he said, “Barbara, ain’t you ashamed of yourself for taking and concealing the money; the taxes must be paid and there must be money somewhere and now let me have it to pay the taxes!” “You lie, you mean scamp!” retorted Barbara, and those were her last recorded words on earth. Picking up an ax and a claw hammer in a corner of the kitchen, Adin furiously and methodically beat and smashed her to bloody death with powerful blows of his deadly implements. It couldn’t have lasted long: no one in the neighborhood heard any noise and Dr. H. W. Kitchen’s careful autopsy that afternoon disclosed two wounds capable of causing instant death. In addition, Barbara Adin’s scalp was pounded to splinters, her ear badly slashed with the ax and a large ax-shaped wedge of her brain knocked out. William Adin did not do anything by half measures. Then, dragging her bloody body behind the grocery and screening it with a partition, Adin took his mare out of the stable, hitched up his delivery wagon, threw his bloody hammer into it and started out for the east side of Cleveland.

Adin left his home shortly after 6 in the morning. He was in no hurry, apparently, as he drove to a downtown market, picked up a parcel of meat at the Central Market (intersection of Ontario, Woodland and Broadway) and delivered it to one of his regular customers on Garden St. (Central Ave.) One of his acquaintances, a Mr. Busch, saw him on Garden St. and hailed him, whereupon Adin asked him the time, was told it was almost 7 am, and continued on his way in his rig. Seconds later he turned south onto Forest Ave.

Somewhere, a few doors north of Mrs. Elizabeth Benton’s home at 900 Forest, Adin tethered his mare to a telegraph pole. Michael Burke, who lived near the Benton home on Forest Ave., watched him do it and also noted the affectionate care with which he carefully draped a horse blanket around the winded and chilled horse. A short time later, Kasander Sabb, a black man, saw Adin put something into his coat as he opened the gate to the side path to the Benton’s back kitchen entrance. Neither man thought anything of it — William Adin and his express wagon were a familiar sight in Cleveland at all hours and anyone who had lived there for any time had a least a nodding acquaintance with the burly expressman.

Elizabeth Benton, a pleasant, 30-year-old housewife, was on the side porch adjacent to the path as Adin passed by. Her husband George had just left for work downtown and she was shaking out the tablecloth crumbs from the breakfast she had just finished with her houseguest, Hattie McKay, when Adin brusquely asked , “Where is Hattie?” “In the kitchen,” replied Elizabeth Benton, no doubt wondering what new mischief her friend’s stepfather was about.

She soon found out. Climbing the back stairs, Adin entered the kitchen and slammed the door behind him. Accosting Hattie, he demanded she return home with him. She refused, and, without another word, Adin pulled out his bloody claw hammer and began hitting her in the head. Neighbors who heard but did not see his mayhem, later described the noise it made as sounding like “someone breaking coal on the floor.” Hattie never had a chance: the first blow knocked her to her knees and her stepfather continued his work until her skull was a splintered wreck with her brains actually oozing out. Adin seems to have been aiming strictly for the top of her head; Hattie’s other injuries, including a broken jaw and facial injuries were incurred as she desperately tried to turn away from his relentless hammer.

No one remembered hearing Hattie scream, but Elizabeth Benton somehow became aware of the trouble in her kitchen. Forcing open the door, she confronted Adin as his encrimsoned hammer rose and fell. As he later resentfully recalled, she “flew at me like a cat,” desperately trying to halt his assault on Hattie. Turning his back on the prostrate and unconscious Hattie, he snarled, “You are the cause of all this!” and proceeded to hit Elizabeth again and again . . . and again with his heavy hammer. When she stopped moving or making any noise, he returned to hammering Hattie. A few seconds later, Mrs. Benton revived and tried to crawl out the door, only to be dragged back into the kitchen and beaten some more by the methodical Adin.

The entire lethal scene probably only lasted a minute or two. No one except Adin himself witnessed the complete the entire sequence of events, but bits and pieces of it were glimpsed by various witnesses. Although beaten almost as badly as Hattie, Elizabeth Benton actually survived long enough to describe seeing Adin from the porch and what happened when she entered the kitchen. Lizzie Arnold, a 14-year-old girl who was living at Maggie Corrin’s house next door, saw Mrs. Benton shaking the tablecloth, saw Adin enter the back door and then watched through the window as he repeatedly hit someone on her knees with a hammer. And Mrs. Corrin and her houseguest Emma Tarbet both saw Adin as he left the back door, walked “leisurely” down the side path, through the gate and to his wagon. As he passed through the gate by the sidewalk, Mrs. Corrin heard him say, “I am ready to go now,” and then both she and Emma watched him throw his hammer into his wagon and drive off.

Realizing that something was amiss, Maggie Corrin ran from her house and into the Benton kitchen. The scene she found there was almost indescribably grisly. There was blood everywhere, on the walls, ceiling, door and kitchen utensils. Hattie was lying in a pool of her own blood, her head a pulpy, smithereened ruin. Mrs. Benton was on her hands and knees, blinded by her own blood, moaning, “Hattie! Oh, Hattie! Oh, Hattie!” As Mrs. Corrin watched in paralyzed terror, Elizabeth pushed the door open, crawled outside on her hands and knees and tried to climb the side fence. Pulling herself together, Maggie Corrin managed to carry her back to a sofa in the kitchen and then she sent for medical aid and the police.

Shortly after 7 am, Adin arrived home, after exchanging the usual mundane greetings with acquaintances he met along the way. As was his habit, he opened up his grocery for business, pulling the shutters down and preparing for the day’s custom. Christian Boest, a neighbor with his own store across the street, had been waiting for Adin to open his store — like many neighbors he practically set his clock by Adin’s regular habits — and he entered Adin’s grocery about 7:30 am. “What’s up?” he said to Adin. “Oh, nothing,” replied Adin, who must have been only 12 feet away from his wife’s bloody body behind the partition when he made his casual reply. The two men traded commonplace pleasantries for a moment and then, as Boest no doubt expected, William Adin brought up the subject of his family troubles. Recounting his early morning argument with Barbara, he complained with intense anger that she had called him a liar and that she had said she didn’t care what happened to him. Boest, who had heard this kind of talk many times before, remarked that he had thought they had become reconciled of late. “Well,” responded Adin, “that was her cunningness. After she tried the law on me, she thought she had better keep still and get it in that way. I married her for pity’s sake, thinking she was a nice woman.” Recalling again that she had called him a “liar,” Adin said, “I saw that things were bad and I might as well have the worst. I am now having a settlement for all past wrongs.” Thinking he meant a financial settlement, Boest asked when it was going to take place. Adin’s cryptic reply made little impression on Boest, who was probably not even listening to Adin’s all-too-familiar litany: “Well, it will all be out, and in a few moments you will know all, anyhow.” Boest did ask where Barbara was but, after saying she’d been sick, her husband added, “I don’t think she’ll be ’round her no more.” No one seems to have ever asked Christian Boest whether he thought it strange — or even noticed — that his neighbor William Adin was thoroughly bespattered with his recent victims’ fresh blood.

Boest left the store about 8 am and fifteen minutes later Sgt. Henry Hoehn and another Cleveland policeman drove their buggy into his yard. Adin had made no attempt to disguise himself or conceal his actions on Forest St. and Hoehn had started in hot pursuit of the hammer killer within 30 minutes of his ghastly rampage. (Little more than eleven years later, Sgt. Hoehn himself would be very nearly killed with an iron coupling pin, wielded by a ruthless “Blinky” Morgan in the rescue of one of his confederates from police custody on a train stopped in Ravenna). Jumping from his rig , Hoehn went up to Adin, who was pumping water for his mare, and said, “Are you Adin?” “Yes,” said the expressman, “and I know what you want.”

What Adin wanted, naturally, turned out to be something a little different than what Hoehn had in mind. Telling Hoehn he needed to get a dog chain from his house, he tried to close the door behind him but made no resistance when Hoehn pushed by him into the store. Walking to the end of the counter, Hoehn espied the bloody body of Barbara Adin. “My God!” shouted Hoehn, what is this?” “Well, said the entirely unflustered Adin, “as you are here, you might as well know the whole of it.” Pointing dramatically at the body, he said, “There lies the cause of all my troubles. Now here’s the whole business: I killed her this morning.” Then, picking up his bloody hammer and ax, he handed them to Hoehn, saying about the ax, “This is what I killed the old woman with.” Hoehn would often subsequently recall the hideous detail of Barbara Adin’s false teeth lying on the floor, scant inches away from her smashed and disfigured head.

Hoehn had seen more than enough and wanted to put Adin in a secure cell as soon as possible — there had been angry talk of lynching him within minutes of the affray on Forest St. But Adin refused to leave just yet, insisting on arranging for the care of his dog and mare before he was taken away. When the impatient Hoehn grabbed him by the collar, Adin eyed him icily and warned, “Now you want to keep cool and don’t handle me that way.” And so it was that Hoehn fretfully trailed Adin as he methodically made his arrangements, trudging back and forth several times from his own house to those of several of his neighbors. His chores finished, he graciously allowed Hoehn to take him into custody and onto the Central Police Station on Champlain St. His parting words to Christian Boest as they drove out of the yard were, “Take good care of the mare.”

At the beginning, at least, Adin made no attempt to conceal either his long-germinating motives or his bloody acts. Conversing cheerfully and calmly with Sgt. Hoehn on his journey to jail, he repeated the well-worn rosary of his family woes and showed no concern for his victims or even any apprehension of the likely consequences he was going to face. Bragging of the speed with which he had traveled from his store to Forest St. on his fatal morning errand, he ingenuously boasted, “But my mare can travel very fast when I let her out.” Well did that very afternoon’s Plain Dealer account of the tragedy opine that “the demeanor of the prisoner during the interview conveyed the impression that he either did not realize the enormity of the crime or was lost to all sense of feeling.” When informed, to his surprise, that Hattie and Mrs. Benton were still living, he expressed his disappointment freely, both to Hoehn and many others throughout that terrible day: “I wanted to put an end to all the damned whelps. They drove me to it. I’m sorry–I meant to make a clean sweep and fix the crowd.” He also expressed regret that he had not been allowed the opportunity to kill his beloved mare, worrying that she might be mistreated by another owner. When asked if he cared more for his horse than his late wife, Adin replied, “Certainly I do!”

Even as he uttered and breezily repeated such inhuman sentiments Cleveland’s medical, police and legal infrastructure began to grapple with the consequences of Adin’s bloody work. Coroner T. Clarke Miller’s inquest heard three witnesses, returned a verdict of willful murder by 4 pm of the murder day and William Adin forthwith engaged the legal counsel of attorneys Carlos B. Stone and Henry McKinney. Barbara Adin’s funeral took place the following Wednesday at the Congregational church on the “Heights” and it was said that to the eyes of the crowd that filed past her open casket there was “scarcely anything about the head to be seen that would indicate the terrible death. It was turned enough to the left to conceal the frightful wound just beneath the jaw and in front of the left ear, while the fearful wound on top of the head was carefully covered with hair.” Following the obsequies, Barbara’s coffin was taken to Woodland Cemetery for burial.

Despite her appalling injuries, Hattie McKay lingered until the morning of Friday, December 10. Fortunately, she was unconscious for most of her last hours, although it was reported that the occasional “moans she uttered were heart rending.” Her funeral took place the next day at the Memorial Presbyterian Church at the corner of Cedar and Case Ave. (East 40th St.) “Tastefully dressed in white and placed in a beautiful coffin,” her corpse too, “had been so treated after death as to retain scarcely any indication of the deadly assault, while the wounds on the head were so dressed as to be hardly perceivable.” Rev. Horton, who preached her funeral sermon, insisted that she had forgiven her stepfather before she died, but given her persistent coma, that might have been piously wishful thinking on the Reverend’s part. Then it was off to Woodland Cemetery to join her mother. Mrs. Benton, sad to relate, somehow survived for five weeks after Adin’s assault, finally succumbing to her horrible wounds on Saturday, January 8. Whether she forgave her murderer is unknown but unlikely, as she was often conscious enough to suffer audibly from the effects of her injuries.

Considering the state of public feeling in Cleveland against William Adin, he received a reasonably fair trial. From the moment that his crimes became known, there was open talk in Cleveland streets of vigilante justice and on several occasions, as he was being taken to and from court, cries of “Hang him to a lamppost!” and “Someone get a rope!” came from the angry crowds watching him cross Public Square. The sole indictment against him was the murder of Hattie McKay. This prosecutorial strategy was no doubt chosen because her murder was the easiest of the three for which premeditation and deliberate malice could be proven. Potential indictments for the murder of his wife and Mrs. Benton were held in reserve, just in case he escaped hanging for Hattie’s murder.

Although he still expressed no remorse for his bloody deeds, Adin’s demeanor and potential defense began to shift subtly as his February court date approached. While still adamant that his victims had deserved death for their wrongs against him, he soon began to insist that he could not remember anything from the moment he picked up the ax in his kitchen until he drove his rig back to the “Heights” two hours later. And as early as Monday, December 6, only two days after the murder, he began to complain that he had been suffering from severe headaches for the past two years. As a cynical Plain Dealer writer noted, “This gives rise to the suspicion that he intends to try the insanity dodge, though no one who has yet seen him believes that he is at all deranged, mentally.” Not that Adin really thought that such an excuse was necessary, mind you. As he told his many visitors over the 10-week prelude to his trial, he fully expected to be acquitted, convinced that the expected disclosure in court of his family problems would exonerate him: “But I mean that everything about our troubles will come out then, and the people will understand it.”

The people, at least those 12 good men and true on his jury, got their chance to understand this peculiar man on Monday, February 21, 1876, when his trial opened before Judge Edwin T. Hamilton in Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court. Defended by McKinney and Stone, Adin was prosecuted by the redoubtable Samuel Eddy and William Mitchell. But it took quite some time to winnow out those twelve men, as, over the next week, 163 men out of 200 men called in four venires, were closely interrogated to discover whether they had preconceived opinions on the case or a disqualifying antipathy to capital punishment. Anyone who had read about the case in the newspapers was particularly suspect, and the Plain Dealer displayed considerable mirth in its extended commentary on the ironies and contradictions of the jury selection process:

The Adin case illustrates how stupid a man must be to serve as a juror . . . In some cases [of juror examination] it was astounding how some candidates had read all reports of the triple murder and yet had formed no opinion as to the guilt or innocence of the accused . . . So far almost every examined has either read a newspaper account or has formed an opinion. Among the accepted jurors so far is an ex-member of the board of education but he will probably be peremptorily challenged — on the grounds of intelligence, perhaps . . . One was examined yesterday who said he had no conscientious scruples against hanging and when questioned further said he had no conscience. Thus the work goes bravely on, men who read the newspaper and form opinions being rejected.

Eventually, the Plain Dealer scribe so despaired of the jury process that he suggested that Summit County undertake Adin’s prosecution, as a payback for Cuyahoga’s service in the matter of James Parks.

Adin’s trial lasted until Saturday, March 4, 1876. The defense’s concern about newspaper coverage proved irrelevant, as virtually all of the testimony offered had already appeared in news accounts of the three inquests and printed interviews with the incessantly chatty Adin. Otto Schuardt and Christian Boest recounted their conversations with Adin on the murder morning. Maggie Corrin, Emma Tarbet and Lizzie Arnold testified to what they had seen at 900 Forest St. on December 4. Lizzie, articulate beyond her years, was an especially persuasive witness and the only living person who had actually seen Adin wielding his deadly hammer. Henry Hoehn, ex-Cuyahoga County Sheriff Felix Nicola and several others recounted Adin’s many admissions of guilt on the murder day and afterwards. Justice of the Peace Goddard and Sgt. S. J. Burlison of the Cleveland Police Dept. were deposed to offer evidence of Adin’s preexisting malice towards Hattie McKay. Burlison’s testimony was particularly devastating, concentrating on a hostile encounter he had had with Adin shortly after Hattie and her mother fled the house in December, 1874. Burlison, at Hattie’s request, had gone to Adin’s house to retrieve some books she needed for her job. When he told Adin his errand, the expressman became enraged, picked up a hatchet and began screaming at Burlison that he was surprised that such a respectable man was running around with a streetwalker like his daughter. When Burlison asked him why he had the hatchet, Adin said, “For protection,” and Burlison ultimately departed without the books.

Burlison’s testimony triggered the only real moment of excitement in the trial. As he spoke, Adin, who hitherto had kept his face slumped in his arms on the table, raised his head and shouted, “Oh, you liar, as you be!” His sister Esther immediately ran to his side and calmed him into silence while he smirked, as if he had said something funny and winked at a nearby reporter. Adin, of course, had his own self-serving version of his confrontation with Burlison, which he had offered to a Cleveland Herald reporter two days after the murder:

Sergeant Burlison strutted in then and I said to him, “Burlison, you are out of your place, if you arrest me I’ll jerk you like everything;” I said further, “If you take those buttons off and stand up fair for me, I’ll soon see which is the better one.”

As in the case of Stephen Hood, the evidence brought by the defense to support their insanity defense was pretty insubstantial. Several acquaintances of Adin testified as to his exemplary character before the triple murders but Messrs. Stone and McKinney doubtless knew that such testimonials were legally irrelevant — just as Prosecutor Eddy would point out in his closing argument. Adin’s sister Esther, who lived on Sterling Ave. (East 30th St.) swore that their paternal grandfather, known as”Crazy Jonas,” had been insane and confined to a locked room during his last years. George Aleberry, who had emigrated with Adin to Cleveland in 1852, corroborated Esther’s story about Jonas, but his dramatic tale of Jonas chasing him with a knife was deflated by his admission that George and his friends had been tormenting Jonas and trespassing on his land at the time. Esther also claimed that she had lived with her brother just after his wife and stepdaughter left in December, 1874 and that she had noticed much absentmindedness, insomnia and depression in his behavior. But her observations were undercut by Adin’s own personal physician, Dr. G.C.E. Weber, who admitted under Eddy’s cross-examination that there was nothing in Adin’s behavior that led him “to suspect that there was any mental alteration.” Weber had noted that Adin was unusually obsessive in talking about his family problems during his last meeting with Adin but that didn’t count for much. And Dr. Proctor Thayer, perhaps the most respected physician in Cleveland, was called by the prosecution as an expert witness to state that he had found no evidence of insanity during his 30-minute examination of Adin in jail.

The final scenes of the trial played out as expected. While Adin sat at the defense table, indifferent, with his head buried in his arms, William Mitchell opened the final arguments, strongly mocking “the insanity dodge,” altogether “the last resort of those who have committed the most hardened crimes.” Carlos Stone responded by reminding the jury there was “no greater calamity than to make a man suffer for the commission of an offense which he could not help committing.” It would be murder to hang Adin for killing his stepdaughter, Stone continued, given his family history of insanity and his severe “monomania” concerning his family problems. Henry McKinney continued in the same vein, stressing the bad strain inherited from “Crazy Jonas” and Adin’s ill-health as testified to by his sister. In his cleverest ploy, McKinney turned the prosecution’s overwhelming evidence of Adin’s oft-expressed malice and overt public violence on its head, arguing that Adin’s frequent threats and his lack of dissimulation in performing the murders — his “cold, calculated actions” — were exactly how an insane person would act. Eddy closed for the State, emphasizing the evidence of premeditation and malice and insisting that the burden of proof for Adin’s insanity rested with the defense — and the defense had clearly not proven it.

After Judge Hamilton’s instructions, the jury went out at noon on Saturday, March 4. As the long hours of deliberation passed, Adin chatted freely with newspaper reporters, airing his opinions of how the trial had been conducted and his confident conviction that he would be found innocent. As the afternoon waned into evening, he began hedging his conjectures towards a hung jury but maintained his overall optimism. As for himself, he averred, after his acquittal he might consider a career in local politics. Indeed, he fancied that he could perform ably as a professional juror, given his present experience, and that he “would do pretty well at that work.”A Cleveland Leader reporter caught his mood of feckless, egotistical optimism perfectly in comments two days later:

There was in his utterances neither the unthinking stupidity of a man who could not realize his peril, nor the bravado of a desperate criminal, but rather the philosophical coolness of a man who felt that he was right and was not fearful of the consequences.

Part of Adin’s self-assurance, it was subsequently disclosed by his attorney, Carlos Stone, stemmed from his uncritical acceptance of a phrenological profile performed on him by a Professor O.S. Fowler in January, 1875. The gospel according to Fowler could only have exacerbated Adin’s already overweening megalomania:

You, sir are one of the greatest workers anywhere to be found . . . you always appreciate the useful and substantial; are endowed with an uncommon amount of sagacity and discernment; are eminently intellectual, a man of real, sound, strong sense and discernment . . . have an intuitive perception of truth and character . . . are calculated to make a good husband; are naturally fond of children . . . are trusted implicitly by all who know you . . . are just as honest and honorable as any man can be . . . have a terrible temper, yet you govern it well . . .

A less flattering portrait of the triple murderer, limned by a Leader reporter, may have caught Adin’s measure with more accuracy. Commenting on Adin’s picture in the paper, he noted:

The eyes set close together, give to the face a somewhat crafty look, which is called out far more distinctly when he is narrating some exploit in which his native cunning was brought into play, than when the face was in repose, as at the time the picture was taken. A side view, however, brings out more cruelty of expression, as the chin recedes and the mouth and nose set out together, strong and prominent, giving one an idea that, were the four large front teeth to once take hold, it would be hard to make them let go.

Apparently Adin’s intuitive discernment was not working well that day, as his jury returned, just after midnight on Sunday, March 5 with a verdict of Guilty of Murder in the First Degree. It was subsequently rumored that they had spent the dozen hours of deliberation overcoming an initial 11-1 deadlock but all twelve men refused to talk about it, then or later. As the verdict was read, Adin’s face turned a deathly pallor and his stupefied surprise was all too apparent. Seconds later, Judge Hamilton heard Stone’s motion for a new trial and, after both sides waived argument, briskly rejected it. He then pronounced sentence of death on Adin, remarking, “The facts proven present a case of uncommon enormity and brutality . . . scarcely paralleled in the annals of criminal jurisprudence.”

Which, of course, was not William Adin’s opinion. Taken back to a death row cell, he fulminated to anyone who would listen that the verdict was an outrage, a “premium on robbery and vice,” not to mention a lost opportunity for his jurors “to rebuke women who rob their husbands, or young girls who will not obey their parents or guardians.”

Recurring to his ambition to become a professional juror, he stated that had he been on the jury he would have stood out for complete acquittal for at least three weeks. As ever, he demonstrated no remorse for his dead victims at any time. He told one auditor that he was looking forward to Heaven but that he didn’t expect to see Hattie, Barbara or Mrs. Benton there, saying, “They are not fit to go to that place.”

Adin’s lawyers went through the motions of appeal but the fight to save his life wasn’t waged with much vigor. The main point of contention was the question of whether Judge Hamilton had acted legally in imposing a death sentence on a Sunday but all parties concerned were well aware that a successful appeal would inflict two more murder trials on a city and a legal system that had already had a bellyful of William Adin. Adin, perhaps in reaction to his increasingly bleak prospects, soon dropped his ingratiatingly chatty style with newspaper reporters. As his days dwindled down to a precious few, he began to blame them for his predicament, insisting that they had biased the jury against him. Eventually, as he last week loomed, he physically assaulted a Cleveland Leader reporter who sought a jailhouse interview.

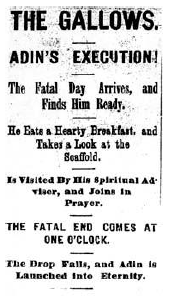

Meanwhile, the dreadful work of summary justice resumed its wonted routine. Owing to the fact that the old County Jail had been razed, Adin’s hanging was held within the confines of the Central Police Station. As his last days crept by, he could hear the sounds of the scaffold timbers (the same reliable device used since 1855) being hammered into shape and the periodic thunk as sandbags used to test the drop mechanism fell to the ground. As had become the custom in Cleveland executions, Adin’s spiritual counsel was provided by the Rev. Lathrop Cooley, assisted by the Rev. J. G. Bliss. To the end, Adin evinced no apparent response to Cooley and Bliss’ spiritual appeals but he never yielded, either to morose despair. Just the night before his death, he caught a glimpse of the gallows while taking his regular walk and commented to his turnkey, “Look, Joe — there’s my flytrap!”

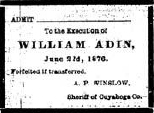

Adin’s execution was the usual coveted ticket for Clevelanders of an inquiring mind and morbid curiosity. Although Sheriff A.P. Winslow had elaborate partitions built to screen the 50′ by 50′ hanging court from watchers outside the police station, he nonetheless issued hanging tickets to an audience of over 260 persons. One of them was George Benton, who stood at the foot of the scaffold until it was over, smoking a cigar and articulating his satisfaction with the proceedings. Another spectator was an anonymous Cleveland Police lieutenant, who expressed his views in hanging-day versification:

Adin, thy crimes will be remembered long,

And son to son the tragic story tell.

Three hapless victims in thy vengeance slain,

And naught could stop thee in thy murderous spell.

What was it led thee to commit the act,

The powers that held thee in such fearful spell?

We’re ready to insinuate the fact

‘Twas inspiration from the pit of hell

With thy dark record of revolting crime.

Thy hands imbued in helpless women’s blood;

You’ve expiated all you can in time.

We leave thee to a just and righteous God.

Adin’s last 24 hours were a perfect microcosm of his life. Meeting with Rev. Cooley on the afternoon of June 21, 1876, he prayed with him, asked forgiveness — and then launched into a lengthy tirade of how the three women “had driven him to it” and deserved their gory fates. After sleeping like a baby for seven hours, he awoke at 4 am and breakfasted on coffee, ham and bread, after which the Revs. Bliss and Cooley appeared for more prayers and photographer Jerry Green set up his cameras in the court to record Adin’s last moments. The crowd of lucky ticket-holders was admitted at noon and at 12:40 pm, Sheriff Winslow and his deputies went to Adin’s cell. Declining to make a statement, Adin took the Rev. Cooley’s arm and walked down to flights of stairs to the hall, out the door and into the gallows area. Adin’s last recorded words were an astonished, “Oh, my! Look at this!” as he walked through the crowd to the gallows. Wearing a new black suit provided by the County, Adin mounted the scaffold with a firm step and sat down in a chair as Cooley read from the 51st Psalm. At 12:58 Sheriff Winslow asked Adin if he wanted to say anything but he just shook his head. Several minutes later, he was placed on the trap, his hands, arms and legs secured and the black cap pulled down over his head. At 1:06 Winslow triggered the drop and Adin fell down seven feet and hung there in sight of the crowd, his tongue grotesquely sticking out and not moving a muscle. His pulse ceased beating at 1:20 and his body was cut down and removed at 1:27.

Before burial in Woodland Cemetery, Dr. Proctor Thayer and some other physicians performed an autopsy on Adin’s corpse. This had been Adin’s last and dearest wish, as he was convinced that his brain would prove to be an abnormally large and impressive organ. He would have been disappointed: his brain, of unusually coarse texture, weighed a mere 43 ounces, about average for a man of his size, and the only medical anomaly noted in the post mortem was the unusual amount of blood — about two quarts — that the doctors found in his brain cavity. The autopsy also confirmed that Adin’s neck had not been broken by the fall but that death had probably come quickly when the ligaments holding his brain in place were torn loose by the shock of the drop.

There was one final, appropriately macabre echo of the Adin tragedy. When his corpse was examined just before burial, it was discovered that his heart was missing. An investigation spurred by Adin’s irate sister, Esther Hague, revealed that one of the autopsy physicians, inspired by medical curiosity, had concealed it in a newspaper and spirited it out of the post mortem chamber. After some legal machinations, Mrs. Hague recovered the missing organ and it is to be hoped that it sleeps to this day in the body of its owner.