Section IV: Ethnic Dynamics in American Society

Cultural Variables in the Ecology of an Ethnic Group

Christen Jonassen

The attempt to discover, describe, and explain regularities in man’s adaptation to space has long been a matter of concern to social scientists and sociologists. In the United States the ecological school of sociology, depending primarily on the observation of man in an urban environment, has concerned itself with this problem. Since Alihan’s shattering critique[1] of the Parkian ecological theory a decade ago, two schools of thought seem to have emerged. Their discussions have sought to determine whether or not a science of ecology is possible without a socio-cultural framework of reference. The crux of the problem seems to center around the relative influence of “biotic,” strictly economic, “natural,” and “sub-social” factors on the one hand, and socio-cultural elements on the other hand. Those stressing the former as causative factors have been referred to as the “classical” or “orthodox” ecologists,[2] while those emphasizing the latter factors might be called the “socio-cultural” ecologists.[3]

Perhaps the best if not the only way to determine where the correct emphasis should lie is by empirical research. It is hoped that the results of a research project[4] reported in this paper may contribute toward that end.

One writer suggests “that the time has come when we should study the influence of the cultural factor in the phenomena sociologists have defined as ecological.”[5] The study of an ethnic group in an American urban environment seems particularly suitable for such a project. Such a group has a distinct culture which can be described and characterized, and the reaction of such a group to the American environment is more readily observed since it is set apart from the general population in the Census and other governmental reports.

The Norwegians in New York have a continuous history[6] as a group since about 1830 when they formed their first settlement and community in Lower Manhattan. Since that day the community has moved until it is now located in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn.[7] The first location was .25 mile from City Hall, the center of the city; the present location is about ten miles from that point. From 1830 to the present time six fairly distinct areas of settlement may be observed.

I. The Problem

We shall be primarily interested in the mobility of the Norwegian community. Why did the group first settle where it did, and why did it move from this area to another? We shall want to know why it moved in one direction and not in another, and we shall be interested in the rate and type of movement. And if we are able to suggest some answers to these questions, we shall be able to ascertain if the distribution of the Norwegian group in New York and the movement of its community can be explained in terms of factors that are “non-cultural,” “sub-social,” “impersonal,” and “biotic,” as the classical ecologists and their followers would contend; or if causality must be referred to cultural and social factors to explain the movement of this community in New York, as the “socio-cultural” ecologists would maintain.

II. Cultural Background of the Settlers

If we are to ascertain the comparative influence of culture in determining spatial distribution , it becomes necessary to sketch briefly the cultural background of this group so that their values and cultural heritage may be indicated. The Norwegians who created this settlement, unlike those who pioneered in the Western states, came for the most part from the coastal districts of Norway. Norway was in those days underdeveloped industrially and its main means of livelihood were agriculture, lumbering, fishing and seafaring. Many individuals would combine all of these occupations and especially fishing and agriculture which were carried on in the innumerable fjords and inlets of the long indented shoreline of Norway. In these districts a culture based primarily on the sea as a means of transportation and a source of food combined with a little farming has flourished for centuries since the Viking days. The people are trained from their earliest youth in skills necessary to make a living in such an environment. The men and women who founded and continued the Norwegian settlement in New York originated in such environments, and many men joined the colony by the simple expedient of walking off the ships on which they worked as sailors.

Norway, of all the civilized countries in the world, has one of the most scattered populations, the density being only 23.2 persons per square mile as compared to 750.4 for England and 41.5 for the United States.[8] Norway does not have very large cities and its people never live far from the mountains, the fjords, and the open sea. They are for the most part nature lovers and like green things and plenty of space about them.

III. Settlement and Movement of Norwegians in New York

The first Norwegian community which has an unbroken connection with the present one was located about 1830 in the area now bounded by the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge, and the East River.[9] At that time, along this section of Manhattan were located docks where ships from all parts of the world loaded and unloaded, and here were also located the only large drydocks in New York, capable of repairing large ocean-going vessels. Here also were found the offices of shipping masters, vessel owners, and other seafaring occupations. In this atmosphere of salt water and ships, men familiar with the sea could feel at home. And within walking distance of their homes they found plenty of work as carpenters, shipbuilders, sailmakers, riggers, and dock and harbor workers.

Across the East River lay Brooklyn, a town of some 3,298 inhabitants in 1800. It grew rapidly and became an incorporated city in 1834, and by 1850 it had grown to 96,850 inhabitants. In 1940, the Borough according to Census figures had a population of 2,698,284. Brooklyn gradually superseded New York as a shipbuilding, ship repairing, and docking center. There was the New York Navy Yard in Wallabout Bay. But the center of shipping activity became Red Hook, that section of Brooklyn jutting into the New York harbor, across from the Battery. The Atlantic Docks were completed here in 1848. It also became the terminus of the great canal traffic that tapped the vast resources of the American continent. Here large grain elevators were built to hold grain for ships that came from all parts of the world to load and discharge. In 1853, the famous Burtis Shipyard already employed 500 men, and in 1866 a great celebration was held when the John N. Robbins Company opened two huge graving docks and three floating docks in Erie Basin.[10] These docks could build and float the largest vessels and they were the only such docks in New York outside those in the Navy Yard. Red Hook became a humming yachting, shipping, and ship-building center.

The Norwegians living in New York found the journey by horsecar and ferry tedious and time-consuming. They soon began to settle in Red Hook and the next Norwegian settlement developed in the area immediately adjacent to and north of Red Hook, where a small group of Norwegians settled in 1850. By 1870 the invasion of Brooklyn was gathering speed.

A horsecar, travelling along South Street in Manhattan, took Norwegian ship workers to Whitehall. Here they boarded the Hamilton Ferry to Hamilton Avenue, Brooklyn. Between 1870 and 1910, Hamilton Avenue became the most Norwegian street in Brooklyn and New York.

The colony developed to the north of Hamilton Avenue. The churches moved over from New York and new churches were established. In the Nineties, this section was one of large beautiful homes and tree-shaded streets. The section became better as one went north and became very exclusive at Brooklyn Heights where the grand old families lived. This section occupied in those days a functional relation to the downtown section of Manhattan that Westchester, Connecticut, and Long Island do today. A contemporary wrote, “…the greater part of the male population of Brooklyn daily travels to Manhattan to work in its offices…The very fact that Brooklyn is a dwelling place for New York…a professional funnyman long ago called it a ‘bed chamber.'”[11] It was actually as the saying went “a city of homes and churches.”

Norwegian immigrant girls coming to New York found jobs as domestics in these beautiful homes and Norwegian men, skilled in the building, repair, and handling of ships of all kinds, found plenty of work for their hands in Erie and Atlantic Basins a short distance to the south. The section therefore became a logical location for the development of a Norwegian immigrant community. It offered them everything they needed. The Irish and Germans also moved into this neighborhood, and as it grew more and more crowded the old families moved out. Just as the New Englanders had forced out the Dutch, so now Norwegians, Irish, and Germans were forcing out the New Englanders. The stately old homes were converted to two-and three-family houses, and some to boarding houses. In this neighborhood the Norwegian colony flourished for some decades up to the beginning of the Twentieth Century.

At the time that certain members of the New York community moved away to settle in this area of Old South Brooklyn, others migrated across the liver to Greenpoint in another part of the Brooklyn waterfront.[12] This section was also connected to the old Manhattan community by ferry. There was some shipping activity along this side of the waterfront but it offered only limited opportunity for the particular skills of the Norwegian immigrants. The area was soon invaded by new immigrants from the south of Europe and by factories of various kinds. It is rather significant that unlike the settlement in Old South Brooklyn this community did not move to adjacent territory, and after some years it ceased to exist, its inhabitants scattering in all directions.

The inexorable growth of the city continued. In old South Brooklyn, open places became fewer and fewer and green grass and trees disappeared. Old large one-family houses were torn down to give place to tightly packed tenements. Then it came the turn of the Norwegians, Irish, and Germans to be invaded and succeeded by the southern Europeans, mostly Italians from Sicily.

By 1890, many old downtown families purchased fashionable homes a little further out near Prospect Park, in the Park Slope section, as “a means of getting away from the thickly populated section of Brooklyn,” the incentive being the scarcity of houses, plenty of wide open spaces and an abundance of trees and garden spots in the Park Slope area.[13] The residents of the area used to be known as the brownstone people who lived in beautiful mansions, paid their bills monthly, and ordered from the store by telephone. In the beginning of the century, the Norwegians also started to move out of the downtown area and into this section. This became the next center of the Norwegian colony in Brooklyn.

But the city continued to push its rings of growth further and further out and the same process repeated itself allover again. By 1910, the Norwegians were on the move again, this time to the adjoining area of Sunset Park. The docks and shipyards were extended all the way out to Fifty-ninth Street. And in 1915, the Fourth Avenue subway was completed. Electric cars running on Ninth and Fifteenth Streets and Third Avenue and Hamilton Avenue provided transportation to the shipping center at Red Hook.

The center of the Norwegian colony remained in Sunset Park district up to about 1940. The exodus of Norwegians from this section and into Bay Ridge and other outlying sections is now in progress. It is the sections of Sunset Park and Bay Ridge which now constitute the area of the settlement. The present Norwegian settlement is located on the high ground overlooking New York Harbor. For the most part it is a section of one-and two-family houses with small lawns, backyards, and tree-planted streets. The nature of this area was determined by indices which have proved reliable in characterizing urban neighborhoods. Indices of economic status, rents, condition of housing, density of population, mobility rates, morbidity and mortality rates, demographic characteristics, standardized rates of crime and juvenile delinquency, dependency, poverty and desertion rates were also employed. From the cumulative evidence of such data it is apparent that the area in which the Norwegians live is, when compared with other areas of New York and Brooklyn, one of the best, and no part of this area according to this study displays the characteristics of a slum district. However, a detailed study of the various parts of the area shows that it can be divided into areas that, on the basis of the indicated indices, may be designated as “poor,” “medium,” and “best.” The distribution of Norwegians living within these areas is as follows: ten per cent live in “poor” sections, fifty-four per cent in “medium,” and thirty-six per cent in “best” areas. The “best” areas include parts of Bay Ridge and Fort Hamilton which contain some of the best residential areas in New York, while the “poor” areas in the northwestern part of the Sunset Park district have some sections that border perilously on slum conditions.

An analysis of population movements within the area of the Norwegian settlement indicates that the Norwegians are moving out of the northern and western census tracts of the Sunset Park district and into the southwestern census tracts of Bay Ridge and Fort Hamilton. Italians and Poles are moving in from the northeast and Russian Jews are taking over the sections of the northern and eastern periphery of the area vacated by the Norwegians and other Scandinavians.

From the ecological and historical study of the characteristics of the Norwegian community over a period of more than a hundred years, it appears that it has maintained rather consistent characteristics and a functional position in New York since the community was established. Like all other groups, native and foreign, the Norwegians were unable to prevent change of the character of their neighborhood, nor were they able to prevent invasion by other land use and lower status groups; they could maintain the things they valued only by retreating before the inexorable development of the city to new territory where conditions were more in harmony with their conceptions of a proper place to live.

It is apparent from the data of this study that numerous causative factors have operated in determining the location and movement of the Norwegian community in New York: the economic and social conditions of Norway, the economic and social conditions of the United States, the rate and direction of New York City growth, the condition of the neighborhood, available lines of communication between the cultural area and the location of the economic base, and attitudes and values of the Norwegian heritage. Where they were to settle and the rate and direction of movement were thus largely determined by elements of the immigrants’ heritage and the character and needs of the host society of the United States.

Neither one of these factors was the determining one. The Norwegians’ reaction to this urban environment resulted rather from a judicious balance of all these factors. It is clear from old maps that transportation to Bay Ridge was available as early as 1895, if they had wanted to live there. But this was slow transportation by horsecar in the early days, and the downtown area evidently presented agreeable enough conditions. As the city grew, however, these conditions became less desirable to people who valued plenty of space around them and nearness to nature.

It is apparent that the Norwegian immigrants broke away from the original economic base to a certain extent later. This development depended on the advance of lines of transportation and new technological and economic development and on the fact that the Norwegian culture was becoming ever more industrialized, which gave later emigrants new skills and knowledge that they could apply here. The erection of skyscrapers and use of steel construction in New York gave Norwegian sailors jobs as structural steel and iron workers. They were used to working aloft and their experience as riggers made them particularly valuable for this work. In the Twenties, the great building boom provided skilled carpenters with plenty of work.

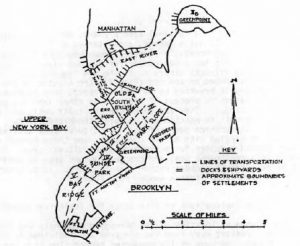

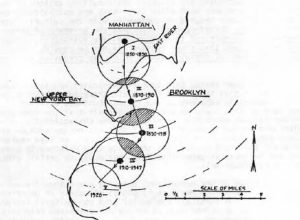

Figure 1 shows the sections the Norwegians have inhabited at various times. The dotted lines represent lines of transportation. Figure 2 is the same map with its salient factors consolidated and simplified. The progression of the Norwegian cultural area, as can be seen, may be represented as a series of interlocking circles, the centers of which are the centers of .the cultural areas at the times specified. The path of this progression is the locus of the centers of the interlocking circles, and it represents in reality the lines of communication.

At each stage, the cultural area presents definite ecological characteristics. It has a center, a clustering of ethnics. The center attracts and repels (Repulsion and attraction here are considered as functions of the choice of individuals in relation to the realities of the environment); it repels some who move out and establish the basis for a new center farther out along the path of advance, and it attracts others to it who are lagging behind. The lagging areas, shaded on the map (Fig. 2), are created at the stage when the colony is breaking up to advance again; they represent transitional areas in process of invasion by other land use and lower status groups. They are therefore the least desirable sections of the settlements to which those who are economic failures gravitate. The advance guard of the new cultural area settled new territory or mingled with native Americans, and these Norwegians in turn formed a center for a new Norwegian cultural area. The process is a continuous one, and change from one area to another must be measured in decades rather than in years. It is a seepage-like movement rather than a sudden mass change.

IV. Some Implications of This Study for Ecological Theory

The change of location of the Norwegian community was produced by persons breaking away from the old area and individually choosing a new habitat. Because of its concerted progression in a certain direction to a certain place, the illusion of a directed mass movement is created. But this ecological behavior arises out of the interaction of the realities of the New York environment with the immigrants’ attitudes and values. The resulting actions of many individuals are very much alike since they are motivated by very similar attitudes created in conformity with the cultural pattern of Norway. It is therefore indicated that the movement of these people must be referred to factors that are volitional, purposeful, and personal and that these factors may not be considered as mere accidental and incidental features of biotic processes and impersonal competition.

It has been stated that immigrant colonies are to be found in the slums or that immigrants make their entry into the city in the area immediately adjacent to the central business district.[14] From the data of this study we are fairly certain that the Norwegian colony has not existed in an area with the characteristics of a slum, and we can be certain that it does not occupy such an area today even though it is the habitat of recently arrived immigrants. It would therefore appear that the statements referred to above can not be taken as generalizations, but apply to certain ethnic or racial groups only.

The cause of the Norwegians’ settling where they did and in no other place around New York is not at all clear if we refer the explanation to biological, sub-social, and non-cultural factors. It is logical to assume that as biological creatures interested primarily in sustenance and survival, the Norwegians could have survived in any number of other places. But if we refer the explanation of the location of their community to cultural factors it becomes so obvious as to be banal. It is clear that their cultural heritage had given them the tools whereby they were able to elicit meaning and values from this particular environment. Other sections of New York, for example the financial section, the clothing manufacturing sections, etc., had little meaning for them in terms of survival or satisfaction. To the Jew from a crowded Ghetto in the center of Poland the realities of the harbor district would probably have no values and meaning, or they might have different values and meanings, perhaps negative values. But to the Norwegian, socialized in the coast culture of Norway, this environment had meaning and value in terms of sustenance and psychological satisfaction. The very method by which he could compete and sustain himself was inherent in the cultural heritage which he brought to this country, and whether or not this cultural heritage should ever find expression and be useful to him depended on the cultural pattern of the United States and the cultural artifacts of that country.

The objective realities of New York thus presented the Norwegians with a multitude of environments to which they might have reacted. It is significant that they reacted primarily to those aspects of the New York milieu that had meaning in their value system. Thus the environmental facts were of little significance per se and only as they were incorporated into the value-attitude systems of the Norwegian immigrants.

The movement of the group, when compared with the movements of other ethnic groups in New York and other American cities, assumes some significance. Studies of Italians[15] and Jews[16] reveal different developments. The usual situation in these groups is one in which an area of first settlement is established which stays in one place, and continues to receive new arrivals. As the old immigrants become assimilated and the second generation grows up, they move out to an area of “second settlement,” usually far removed from the first in space and time. Thus Italian and Jewish communities in New York are still found in many of the areas, such as the Lower East Side of Manhattan and downtown Brooklyn where they were first established. But there is hardly a trace of any Norwegians in the areas of New York and Brooklyn which they originally inhabited. Furthermore, the development and progression of Norwegian cultural areas in New York show a continuum of space and time and result from the unique character of their heritage in interaction with their new environment. It does not therefore seem possible to generalize as to the type of movement that all immigrant groups in urban areas will exhibit; rather the type of movement, its rate and direction will depend on the interaction of the particular heritage of each immigrant group with the urban environment in which the immigrants live. The different rates of movement of different ethnic groups[17] from the center of-cities might find a more satisfactory explanation on this basis.

The area of the Norwegian community was described in terms of indices of various kinds. These might be regarded as objective measures of the values which Norwegians have in regard to the environment in which they want to live. Thus the amount of crowding within the home and congestion without, and other conditions indicated by crime, delinquency, health, and population statistics, have for Norwegians apparently reached an intolerable point in certain census tracts. Other tracts present them with conditions that they find more favorable, and it is to these areas that they move as soon as they are able to do so.

It is probable that the Norwegian community has been able to maintain its solidarity for over a hundred years and in spite of constant moving, because the variable factors that determined its existence were favorable. The dissolution of the Greenpoint settlement indicates what happened when the factors that sustained it were unfavorable. But for the community that did survive and more, there was, when conditions reached an intolerable state, always an appropriate area immediately adjacent to the old area; so the community was able to move from Manhattan to old South Brooklyn, to Park Slope, to Sunset Park, and finally to Bay Ridge. Norwegians have not been segregated from native whites, nor is there any evidence that they have been discriminated against in any way as far as choosing a home is concerned. The clustering within the area is therefore voluntary.

However, there is no place having the characteristics which Norwegians require adjacent to the present settlement in Bay Ridge. The city is moving in on them from north and west, and there is only water to the east and south. The area is also being invaded by other ethnic groups. Nor is the type of buildings within this area entirely to their liking. It is still predominantly a neighborhood of single- and two-family houses, but a great number of large, high class apartment houses have been built, and the land value has increased so tremendously that wherever zoning permits, this is the type of housing that is erected. It would seem that the Norwegian community in Brooklyn is making its last stand in Bay Ridge with its back to the sea. Its final dissolution is a matter of years and will be brought about because the balance of variables that determined its development cannot be maintained much longer. As long as the values of their heritage could be integrated and harmonized with conditions of the developing city, the community grew and flourished; when this integration is no longer possible it will disintegrate and its members disperse.

This development has already commenced. Census figures and the changes of addresses for subscribers to Nordisk Tidende, the newspaper of the Norwegian community, indicate that many Norwegians are moving to Queens, Staten Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut, where new settlements are forming in environments which are more in harmony with the values of their heritage. Some of these settlements have started as colonies of summer huts, and finally developed into all-year round communities.

The peculiar interplay of a plurality of motives that goes into the determination of ecological distribution of Norwegians is well illustrated by these informants:

I like it here (Staten Island) because it reminds me of Norway. Of course, not Bergen, because we have neither Floyen nor Ulrik, nor mountains on Staten Island, but it is so nice and green allover in the summer. I have many friends in Bay Ridge in Brooklyn, and I like to take trips there, but to tell the truth when I get on the ferry on the way home and get the smell of Staten Island, I think it’s glorious. However, I’m taking a trip to Norway this summer, and Norway is, of course, Norway–and Staten Island is Staten Island.[18]

A man states:

I arrived in America in 1923, eighteen years old. I went right to Staten Island because my father lived there and he was a ship-builder at Elco Boats in Bayonne, New Jersey, right over the bridge. I started to work with my father and I am now foreman at the shipyard where we are building small yachts–the best in America. I seldom go to New York because I don’t like large cities with stone and concrete. Here are trees and open places….[19]

Another tells what he likes about his place in Connecticut:

I like the private peace up here in the woods. There is suitable space between the cabins so that we do not have to step on each other’s toes unless we want to get together with someone once in a while. Since I started to build this house, it is as if I have deeper roots here than in the city. This is my own work for myself….[20]

And a woman says:

…It is a real joy to get out of the city with all its wretchedness. I go down to the brook where I have a big Norwegian tub. There I sing lilting songs and wash and rinse clothes. Everything goes like play, and before you know it, the summer is over, and all this glorious time is gone and I could almost cry.[21]

One who has moved to Staten Island weighs the advantages and disadvantages:

It is countrylike and quiet here with plenty of play room for the children. But I must admit I am homesick for Brooklyn once in a while, perhaps often. Then I take the ferry and visit friends and acquaintances there.[22]

The assumption that “in general, living organisms tend to follow the line of least resistance in obtaining environmental resources and escaping environmental dangers” has been used as the basis for hypotheses of human distribution in space.[23] Such a statement in the light of this study seems too mechanistic, too simple, and therefore inadequate as an explanation of the distribution of this group in New York. Men need not merely to survive, require not only shelter or just any type of sustenance; they want to live in a particular place, in a particular way. A better description of man’s distributive behavior might be: men tend to distribute themselves within an area so as to achieve the greatest efficiency in realizing the values they hold most dear.[24] Thus man’s ecological behavior in a large American city becomes the function of several variables, both socio-cultural and “non-cultural.”

One writer has pointed out that the early ecologists “envisaged an abstract ecological man motivated by physiological appetites and governed in his pursuits of life’s goals by competition with others who sought the same things he sought because physiologically they were like him.”[25] It is quite evident now that this ecological creature was the product of the same intellectual miscegenation which begot the now somewhat extinct “economic man.” The men and women observed in this study are not abstract entities; they are very real persons with physical needs. But they are also governed and motivated in the pursuit of culturally determined goals by culturally determined habits and ways of living. They compete for things high in the hierarchy of their value system which mayor may not be the same things for which other individuals and groups strive. It hardly seems possible to achieve a systematic theory of ecology that squares with empirical observation and meets the needs of logical consistency without the cultural component as an integral part of such formulations.

Taken from American Sociological Review, 14 (February, 1949) 32-41 with the permission of The American Sociological Association.

- Milla A. Alihan. Social Ecology, New York, 1938. ↵

- The "classical'" ecological position is perhaps best expressed by: Robert E. Park, "Succession, an Ecological Concept," American Sociological Review, I, April, 1936; "Human Ecology," The American Journal of Sociology, XLII, July, 1936; "Reflections on Communication and Culture," The American Journal of Sociology, XLIV, Sept., 1938; Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, Roderick D. McKenzie, The City, Chicago, 1925; Ernest W. Burgess, Ed., The Urban Community, Chicago, 1925; Roderick D. McKenzie, The Metropolitan Community, New York, 1933; "The Concept of Dominance and World Organization," The American Journal of Sociology, XXXIII, July, 1926. Following the general orientation but differing somewhat from the "classical" position we have: James A. Quinn, "The Nature of Human Ecology--Re-examination and Redefinition," Social Forces, 18:161-168, 1939; "Ecological Versus Social Interaction," Sociology and Social Research, 18:565-570, 1934; "Culture and Ecological Phenomena," Sociology and Social Research, XXV:313-320, March, 1941; Amos H. Hawley, Ecology and Human Ecology," Social Forces, 22:398-405, May, 1944. ↵

- Perhaps the most forceful expression of the position of the "socio-cultural" position is in the writings of: Walter Firey, Land Use in Central Boston, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1947; "Sentiment and Symbolism as Ecological Variables," American Sociological Review, X:140-204, April, 1945; August B. Hollingshead, "A Re-examination of Ecological Theory," Sociology and Social Research, 31:194-204, January, 1947; Warner E. Gettys, "Human Ecology and Social Theory," Social Forces, 18:469-476, 1939. ↵

- See C.T. Jonassen. The Norwegians in Bay Ridge: A Sociological Study of an Ethnic Group, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1947. ↵

- A.B. Hollingshead, op. cit. ↵

- See A.N. Rygg. The Norwegians in New York 1825-1925, Brooklyn, New York, 1941. ↵

- Smaller settlements have also been formed in suburban sections of Staten Island, Queens, and the Bronx, but the main group is located in Bay Ridge. See Figure 1. ↵

- As of 1938. ↵

- See Figure 1. ↵

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 17, 1910. ↵

- Edward Hungerford. "Across the East River," Brooklyn Life, 1890-1915, p. 81. ↵

- See Figure 2. ↵

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 5, 1926. ↵

- Cf. R.D. McKenzie, The Metropolitan Community, p. 241; Ernest W. Burgess, "The Growth of the City: An Introduction to a Research Project,": in Robert E. Park, et. al., The City, pp. 55, 56; Harvey W. Zorbaugh, The Gold Coast and the Slum, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1929, pp. 11, 128. ↵

- Cf. Leonard Covello, The Social Background of the Italo-American School Child: A Study of the Southern Italian Family Mores and Their Effect on the School Situation in Italy and America, New York: New York University School of Education, (Ph.D. thesis), 1944. ↵

- Cf. Louis Wirth, The Ghetto, Chicago, Illinois, 1929. ↵

- Cf. Paul F. Cressey, "Population Succession in Chicago: 1898-1930," American Sociological Review, August, 1938, pp. 59-69. ↵

- Nordisk Tidende, March 3, 1947. ↵

- Loc. cit. ↵

- Ibid., September 5, 1946. ↵

- Loc. cit. ↵

- Ibid., March 3, 1947. ↵

- James A. Quinn, "Hypothesis of Median Location," American Sociological Review, April, 1943. ↵

- This conclusion is essentially in agreement with the "theory of proportionality" as proposed by Walter Firey, Land Use in Central Boston, p. 328. ↵

- A.B. Hollingshead, op. cit., p. 204. ↵