Main Body

Chapter IV: The Frustration of a Black Ghetto

Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.[1]

The two divergent reports that were presented in the weeks following the Hough disturbances carefully attempted to pinpoint the specific causes of the riots. However, the main emphases of the two interpretations were directly in conflict with each other — the Grand Jury Report tried to demonstrate that outside agitators and Communist sympathizers had been the precipitating factors involved, and the Citizens’ Panel Report was primarily motivated to refute the conclusions of the Grand Jury. The story was not as simple as either report told it. Instead, the disorders were caused by a complex and interwoven pattern of events and conditions that produced a general malaise as well as growing frustration within the ghetto. The conditions of Hough and the inciting series of events in Cleveland were closely tied together by the thread of racism — a thread that ultimately led to five days of destruction and violence in July, 1966.

Cleveland, Ohio — A Typical Urban Center

The problems of Cleveland were similar to those of other large metropolitan areas across the country. An old city that grew in the flush of the industrial revolution, it aged rapidly in the mid-twentieth century, challenged by the suburban push on its periphery. Like other cities experiencing suburbanization, Cleveland saw the gradual migration of her industry, her more affluent white taxpayers, and her cherished institutions from the central part of the city to the surrounding communities.

During its fast growth during the booming industrial era, Cleveland developed an interesting mosaic-like pattern of ethnic residential areas. Pockets of ethnic groups were scattered throughout the city, and lines were fairly well drawn between settlements of different nationality groups. Most of the wealthier, older families of the city moved out to the suburbs, which surrounded the city and covered a much higher proportion of the land in the metropolitan area than did the central city. The suburbs had many advantages when compared to Cleveland’s inner city. Therefore, Cleveland found a declining tax base with which to meet new and increasing problems. The largest set of problems that faced the city focused on the high concentration of poor black people in the inner city.

Statistics from the censuses of 1960 and 1965 illustrated numerically the problems of the city. The total population of the city decreased from 876,050 in 1960 to 810,858 in 1965, a decline of 7.4%, while at the same time the black population of the area increased 10.1% from 250,889 to 276,376. Apparently the white population was moving to the suburbs as the black population, because of a very high birth rate and migration from other parts of the country, was growing within the city.

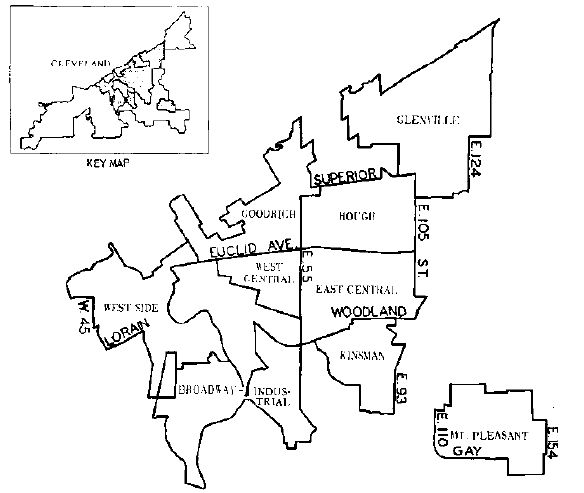

But the black population, similar to other ethnic groups in the city, was clustered and concentrated in a small section of the community. Almost all of the city’s black people lived in neighborhoods on Cleveland’s East Side. Before World War I, most of the Negroes had lived in the Central neighborhood, an area southeast of Hough. The end of the war was followed by a great influx of Negroes who also settled on the East Side and moved the area of concentration to about East 55th Street, the western border of Hough. In the late twenties and early thirties the area continued to move east, but the period following World War II witnessed the greatest change. Neighborhoods such as Hough, Glenville, Mt. Pleasant, and Kinsman became predominantly black in their racial composition. There were almost no Negroes living on the West Side, and nearly half of the few living there resided in public housing.

The segregated pattern of housing was still abnormally high in the 1960’s. Over ninety-one percent of the city’s Negroes would have had to move to different blocks to have attained a normal racial balance (same percentage as entire city) in every block.[2] In the early 1960’s, black people began to migrate to a few of the eastern suburbs, but their movement out of the city was still very restricted. The limited black suburbanization did not help to alleviate the pressure of the increasing black population within the city. It was estimated that about two-thirds of the increase in the black population occurred in areas of the central city which were either biracial or predominantly black.[3] The curious mosaic pattern had resulted in concentrated pockets of impoverished black people. The worst such pocket was known as Hough.

Hough — The Tragic Components of a Ghetto

Causes of unrest and despair among urban-ghetto Negroes, as well as their grim, sobering and costly consequences are found in classic form in Cleveland.[4]

There was an area of two square miles that stretched from East 55th Street to University Circle on Cleveland’s East Side. It was known by the name of the avenue that bisected the neighborhood — Hough. Hough was a black ghetto.

A ghetto is not merely an area of a city. For its inhabitants it is a way of life, a means by which to exist. The people of the ghetto are locked in its way of life and escape is not easy, for the vicious cycle of life that pervades the entire fabric of the ghetto is almost impossible to break. It is a vicious cycle that includes segregated and inadequate housing, unemployment and a dependence on welfare to subsist, poor schools that rarely lead to higher learning, an increasing crime rate, disease and squalor which infest everything and everyone, and attitudes of bitterness, frustration, and defeat. To the visitor, the most noticeable feature of the urban ghetto is its physical ugliness — the dirt, the filth, and the total neglect of the area. As Kenneth Clark stated in his book Dark Ghetto, “The only constant characteristic is a sense of inadequacy.”[5] Another characteristic of the ghetto is that its inhabitants are predominantly black. This fact only increases the barriers faced by the residents of the ghetto. The combined walls of poverty and discrimination are difficult to scale simultaneously.

The ghetto has not been a happy place. Little chance has existed for its inhabitants to fulfill the American dream of social and economic upward mobility. Often exploited by profiteers and politicians, the urban ghettos have stood severed from the outer world by invisible walls of racism and poverty. Many embittered Americans who are black have lived within these walls.

Hough was a black ghetto in 1966. Figures from the special Census taken in Cleveland in 1965 illustrate the problems of the areas. In 1960, the population of Hough was 73.7% black. By 1965, the figure had increased considerably to 87.9% because of the constant stream of white migration to outlying areas. Although the white population of the ghetto in 1965 was only one-third of its level in 1960, the number of black people had only declined a few percentage points. Every census tract in the neighborhood had become predominantly black in the five years between censuses, and everywhere the percentage of black people in 1965 was higher than in 1960. The percentage of unemployed members of the labor force was much higher in Hough than it was for the rest of the city. For males in Hough, the unemployment rate was 13.4% compared to 6.47% for the entire city, and the unemployment figure for females there was almost more than twice the rate for the city. The median number of years of schooling for adults over twenty-five again compared unfavorably, Hough showing a median of 9.7 years completed compared to the entire city’s 10.3 years, and the difference had been increasing over the years. The comparison worsened if the quality of the education became another variable. Most revealing were the income statistics. While the entire city’s median family real income was increasing from $6,325 in 1960 to $6,895 in 1965, an increase of 9.1%, the real income in Hough per family decreased from $4,900 to $4,050, a decrease of 17.3% in the same length of time. Hough also experienced an increase of almost two thousand persons who existed below the poverty level in this five year period, despite the fact that the area had lost population in this time. The percentage of family members subsisting below the poverty line had increased by almost a third in Hough, while for the entire city, the percentage had remained rather constant at a rate one-half to one-third that of Hough.[6]

Hough was also crowded. There were about forty-five persons per acre there compared to a range of ten to thirty-five persons per acre in other city neighborhoods. This crowding was a result of the World War II years, when Cleveland had become an arsenal of the war and thousands of skilled and unskilled workers had migrated to the city.[7] However, unlike the immigrant and ethnic groups who passed through the ghetto stage on their way to social acceptance and suburbia, the Southern black people who migrated to Hough were offered almost no hope of escape. Here they were denied a chance to improve their lot because of their color or some other related factors.[8]

The area did not become a monolithic slum. Neat houses in rows on one street contrasted sharply with the places unfit for human habitation. Hough had formerly been the home of a large segment of the Jewish middle class as well as some of the wealthier families of Cleveland. However, the visible remnants of elegance and better days only served to intensify the aura of decay that encompassed Hough. In spite of the fact that most whites had moved out of the area, many of the small shops, markets, and bars were owned and operated by whites. Many of the rented homes were owned by absentee landlords, and the condition of most of the land and buildings was described by almost everyone as “deteriorating.” Although Hough contained only 7.3% of the city’s population, the area provided nineteen percent of the welfare cases for the entire county.[9] More than one-third of the area’s 1,372 births in 1966 were illegitimate, one-half of them born to teenage mothers. The infant mortality rate in Hough doubled that of the rest of the city, and Hough’s rate of participation in the Aid to Dependent Children Program almost doubled that of the rest of the city. About twenty percent of the major crimes in the city were committed in Hough, and the crime rate there had tripled since 1950.[10] All of these factors coupled with inadequate government services combined to give the ghetto’s residents little reason to care about the neighborhood.[11] As a result, most of the people who lived there did not care about the community, as shown rather effectively in July, 1966, and by the reactions of the community following the disorders. The reactions were similar to those of a tenant in one of the slum’s apartments. “If I come back after death,” he stated bitterly, “I want to come back as a tiger and tear up Hough.”[12]

The businessman driving to him home in the eastern suburbs from his office downtown would see only a glimpse of the life behind the invisible walls surrounding the area known as Hough. Although he would see rows of dilapidated houses and streets with nothing but garish bars and small store-front churches, he could not have much empathy for the dwellers inside the walls nor much understanding of the smoldering fire within the ghetto. The white middle-class experience prohibited full understanding of the black ghetto because the values, institutions, and mores inside the walls of Hough were so different from those of the surrounding areas. Thus, the experience of Hough coupled with a lack of understanding and empathy by the white community helped the vicious cycle to spiral on downward. Few people outside the ghetto realized the consequences.

The Events Preceding the Riots

Disorder did not erupt as a result of a single “triggering” or “precipitating” incident. Instead, it was generated out of an increasingly disturbed social atmosphere, in which a series of tension heightening incidents over a period of weeks or months became linked in the minds of many in the Negro community with a reservoir of underlying grievances.[13]

Many events led up to the precipitating incident in the Seventy-Niners’ Café on July 18. Although some of the events touch on some underlying causes of the riots, those incidents provide the background for a clearer understanding of the disorders. It is necessary to begin in 1963, when Ralph S. Locher, law director of the city, succeeded Anthony J. Celebrezze as Mayor of Cleveland after Celebrezze was appointed Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare.

Mayor Locher’s relations with the black community progressively declined from the moment he became mayor. At first he met with leaders of “responsible” groups to discuss “reasonable demands,” but that effort was discontinued after a while. In the summer of 1963, a mass rape of a white girl by black youths almost incited violence. The group had stabbed the girl’s boyfriend repeatedly in the incident, and mass retaliation and violence appeared inevitable. To avert trouble, Locher asserted his authority and pressed for immediate and heavy punishment. His actions did not endear him to the black community, most of whom felt that the white establishment did not understand many of the deeper sociological implications of the incident. The next major incident occurred in the spring of 1964. Some black citizens and civil rights groups tried to impede construction of a new school in a black neighborhood on the East Side because the school would perpetuate de facto segregation. Locher attempted to resolve the differences by a series of conferences which produced no positive results. The alienation of the blacks from Locher was completed when Reverend Bruce Klunder was accidentally killed by a bulldozer at the site of the proposed school during a demonstration.[14] At this time, Ruth Turner, a graduate of Oberlin College and a full-time CORE worker in Cleveland, commented that Cleveland was a “polarized community by virtue of the fact that a vacuum has been created in the white community through apathy, and that vacuum has been filled by people who would rather scream Communism than address themselves to the real grievances” of the community.[15] Her words, uttered in 1965, were very prophetic.

A measure of the polarization between the black community and Mayor Locher occurred in the spring of 1965, when Locher proposed an income tax of one percent on gross income to generate new revenue and provide new services. The tax was to be used for hiring extra police and firemen, raising the pay of city employees, funding additional staff members for the housing and recreation departments improvement of the street lighting and air and water pollution control and demolition of abandoned houses. The measure was widely endorsed by influential organizations throughout the community, and it was even backed by the Negro-run and owned newspaper, the Call and Post. The tax was opposed by only the Chamber of Commerce, the Citizens’ League, and the NAACP., but the proposal was soundly crushed at the polls, 89,290 to 62,816. The difference occurred because the black wards had voted overwhelmingly against the tax. In Hough, the vote was 3,525 for the tax to 6,789 opposed, and Hough was typical of most of the other black communities in its voting behavior. It was noted that many of the residents of Hough had nothing to lose by voting for the measure because people who were on welfare relief would not have been taxed. Most observers concluded, however, that most black citizens did not favor the measure because the revenues would not have been used to measurably improve the lot of the people in the black neighborhoods and because the black community was very disenchanted with the Locher administration.[16]

The voters had a chance the next November to directly express their dissatisfaction with Mayor Locher in the election for Mayor. The black community united behind a little-known State representative from one of the black wards, Carl Stokes. With the Republican candidate siphoning off a few white votes, Stokes, running as an independent Democrat (after losing the party nomination in a primary), came within 2,000 votes of unseating Mayor Locher. Black power, demonstrated in terms of votes at the polls, had almost succeeded indirectly influencing the decisions to be made at City Hall.

During this period of time, some efforts were made to reach the youths of the ghetto. Unfortunately, these programs were usually failures because of executive, administrative, and planning inadequacies. A good example of such a program was the Com-munity Action for Youth Program (CAY), chartered in 1962. The expressed goals of this program were to decrease juvenile delinquency, to build youth aspirations, to stimulate educational and occupational achievement, and to strengthen the role of the father in the family. However, in the words of one conservative reporter, “CAY turned out to be the biggest bust since Edsel.”[17] The program was reported to have been plagued by many intra-agency personality conflicts and a high rate of personnel turnover. The personnel involved in the program often came in from other communities for “experience,” and as a result were sometimes incompetent and unempathetic, with little understanding of the problems facing Cleveland or Hough. Attempts to give top priority to child neglect and family cases were occasionally sabotaged because of a lack of personnel, low wages, and the press of intake cases in the Hough area. Services to unwed mothers, preadolescent youngsters with learning difficulties, and activities for “aggressive” boys were often inadequate, and the drop-out rate was very high. Many of the proposals for youth camps, after-school programs, and pilot programs for unwed fathers never even achieved reality because of the many problems which beset CAY.

(Notes on Cleveland’s Nine Poverty Neighborhoods)

In 1959 99,138 residents of these nine neighborhoods were below the “poverty line”, by 1964 this number had dropped to 93,424. In 1959 66 per cent of the individuals living in poverty in Cleveland were concentrated in these nine neighborhoods, by 1964 this figure had risen to 69 percent — although in 1964 these nine neighborhoods included only 39 percent of the Cleveland population as compared to 41 percent in 1959.

The number of children under 14 years of age living in poverty in these nine neighborhoods rose from 36,157 in 1959 to 38,166 in 1964 — despite a seven percent decrease in the number of children in this age group in these nine neighborhoods. In all of the City of Cleveland there were 46,560 children under 14 years of age living below the poverty line. This number is approximately equal to the total number of children in that age range in Lakewood, Parma and Shaker Heights combined.

In 1960 less than one-half (47.6 percent) of the residents, five years old and older, had been living in the same house for five years or longer and in Hough only 22 percent had not moved during the previous five years. In 1965 the mobility rate was almost exactly the same (47.2% were in the same house as five years earlier) and Hough again led in mobility as less than one-third of the residents of Hough were occupying the same house that they had been living in back in 1960.

The goals and ideas of CAY were widely accepted within the community. However, the program ended without measurably improving the status of the ghetto dwellers, and many of the workers in the program left for other areas with higher salaries and jobs because of their “contributions” to the Hough community.

In the spring of 1966, the United States Civil Rights Commission held hearings in Cleveland for seven days, and in a report issued later diagnosed Cleveland’s ills to be “the classic ones of the ghetto: inadequate housing, schools and jobs.”[18] The hearings were widely publicized in the city, and many citizens testified about the city’s grave problems. Many of the underlying causes of the disorders three months later were spelled out in detail by the testimony at the hearings. The result of the Commission’s week in Cleveland was a new awareness in both the total community and the black neighborhoods of the deplorable conditions in which the majority of Cleveland’s black citizens existed. Unfortunately, the situation was not improving.

At the beginning of the summer, many Hough residents were among the group of marchers that walked from Cleveland to Columbus in an effort to secure more welfare relief.[19] The group’s request was turned down by an unsympathetic Governor Rhodes, and the long, hot summer began on a rather discouraging note for many of Cleveland vs black citizens. The outlook worsened as the community soon saw racial tension rise to new heights.

Relations between the black and white citizens living on opposite sides of the northern border of the Hough area had always been strained. Negro youths had attacked a white father and son there in January, 1966, and as the school year closed that spring, many anti-Negro signs were painted in a park north of Hough. There were also many instances of interracial fighting that occurred at the beginning of the summer. Black residents of the area became quite perturbed when the attacks continued and police did not seem to do anything to alleviate the tension between the two groups. Finally, on June 22, two black youths were attacked by a gang of whites in the Sowinski area at the northern outskirts of Hough. A crowd gathered after the incident and confronted police with evidence including a description of the attackers and the automobile in which they were riding. The police ostensibly refused to investigate or pursue the youths, and soon rocks and bottles were being hurled at both police and passing cars. Area residents met the next day on three separate occasions with city officials and law enforcement officers, but no positive action was taken in response to the residents’ complaints. That night, fueled by the frustration and anger that had been building up over the months, groups of neighborhood black youths destroyed some property and continued the missile barrage on passing cars. A boy was allegedly shot by a white man in a passing car, and when residents linked the cart to the owner of a neighborhood supermarket, the store was immediately torched. Much damage was inflicted on several other white owned businesses on Superior Avenue in the three nights of trouble that so ominously forewarned of the disturbances in July. On Saturday, June 25, a meeting was held between area residents, youth and the mayor. The group aired its grievances and made specific recommendations to the city’s chief executive, most of which concerned police, recreation, and urban renewal. That night, the disturbances ceased, and only minor incidents of rock throwing along Superior Avenue were reported for the next several days.[20]

In analyzing the situation, Assistant Safety Director Richard McKean had noted that there “was no danger of a Watts riot” in Cleveland. He claimed that he had faith in the “law-abiding” people of Cleveland. Safety Director John McCormick added, “We’re prepared to deal with the situation,”[21] and it appeared that most of the officials closely connected with the safety of the City of Cleveland did not have the foresight that would have enabled them to have quickly and effectively halted the riots in the Hough area once they began. Thus, the disturbances on Superior Avenue were not recognized to be the omen that they actually were. The City reacted as if almost nothing had happened.

As the disturbances on Superior Avenue ended, Ralph Findley, Director of the Greater Cleveland Office of Economic Opportunity, announced the city’s plans to keep the idle youths of the city busy. Cleveland was set to spend almost one and a half million dollars in programs involving inner-city youth, with the federal and city governments paying most of the bill. These programs included opportunities for jobless youngsters to work in their neighborhoods and organize playground groups to keep other children off the streets and jobs to work as playground helpers. Also available to the city’s youth were many jobs in institutions and government agencies, and the school system offered about 1500 jobs for high school students. The Neighborhood Youth Corps and Opportunity Centers sought to aid the students by providing some 1300 jobs, and the Welfare Federation provided opportunities for seventy-five young leaders. The list went on further, and most people connected with the effort to provide jobs agreed that there were enough opportunities to accommodate every youth who desired work.[22] As the hot summer stretched into July, job opportunities had greatly increased for the unemployed youth, but the other events in June had caused a simultaneous increase in racial tension.

On July 1, plans were revealed for the downtown expansion of Cleveland State University. The project was to cost a few million dollars, and the resentment and cynicism that these plans evoked in the black community were plainly evidenced by the negative reactions of such black leaders as Councilman Leo Jackson and Ernest Cooper, director of the Urban League.[23] Obviously, with the problems faced by the black community in Cleveland, its residents would be less than enthusiastic about an expensive project that would not benefit them either directly or indirectly.

Fifty of the black community’s leaders met with Mayor Locher on July 5 to offer their help to the mayor in his efforts to relieve racial tension within the city. The group presented the mayor with an eight point program that they believed would help to meet many of the black community’s problems that had arisen in the previous months. These suggestions to the mayor included a request for the police department to fully support law and order and to treat all persons equally when making arrests. They also called for an investigation into the shooting of a ten-year-old boy during the Superior incidents twelve days earlier, an explanation by the police of the absence of any arrests for the shooting, and an investigation by the police into the source of leadership distributing incendiary race-hatred literature in the black community. The leaders also requested the appointment of a special mayor’s committee to make recommendations to help ease the racial tension, and the ordering of specially trained police into tense neighborhoods, to be kept there until the trouble had disappeared. The group ended its list of suggestions with a broad appeal for racial amity. After the meeting, Mayor Locher stated that the efforts were “entirely constructive.”[24]

However, constructive as the black leaders’ efforts were, the rest of the community remained frustrated and aggravated. Mayor Locher had met with Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Robert Weaver early in the summer, and Weaver had given Locher a list of the city’s responsibilities to improve the stagnating East Side which included measures to uplift the housing, derelict buildings, parking facilities, garbage collection and playgrounds. Locher did very little to satisfy Weaver’s recommendations, and as a result, the city lost a federal grant of $1,500.000 for parks and playgrounds.[25]

Meanwhile, the city’s urban renewal program remained mired in red tape. The University Euclid Project of rehabilitation for part of the Hough area had stood almost still since its inception in 1962. With the goal of rebuilding some of the sturdier structures of the area to preserve and improve the neighborhood, the city had estimated in 1962 that the project would be completed in June, 1967. The project had first been approved by David Walker, then a commissioner of urban renewal for the federal government. The city later hired Walker as a consultant in 1964 to “speed up” the rehabilitation program, but Walker announced in May, 1966, that the project would not be finished by its original target date, and set no date for its completion.[26] By June of 1966, only twelve per cent of the planned rehabilitation had been completed. It was also widely rumored that the federal government would soon cut off all new funds for the badly boggled urban renewal plans.

In Columbus, the State Legislature conducted hearings on proposed legislation that would abolish capital punishment. One of those officials testifying for retention of the death penalty was Cleveland’s Chief of Police, Richard R. Wagner. Wagner claimed that the death penalty was an effective deterrent to many black nationalists who plotted to kill. When the civil rights leadership of Cleveland heard Wagner’s statements before the legislature, they requested again to meet with the mayor in order to air their grievances about the police chief’s attitudes. Mayor Locher would not see them, however, and the group waited in his office for three days in a vain attempt to gain a hearing.[27] When, at the end of the third day of protest, the group decided to stay overnight, the mayor had them arrested and thrown in jail.[28] Tension between the mayor and the black community heightened to the breaking point.

Chicago erupted in violence and destruction on July 12th, 13th and 14th. The damage was not too extensive, but the action was portentous of disorders to come. The events in Cleveland over the months and years before July, 1966, made the city a likely spot for violence and destruction. Tension had heightened, relations had become strained between the city government and the black community, and the social conditions of the black ghetto, the real underlying causes of the disorders, had become intolerable.

The Underlying Social Conditions

Many conditions caused the outbreaks of disorder in Hough. Certainly some factors were much more important and relevant than others, but each contributed to the final outburst of frustration and despair which exploded on Cleveland’s East Side for those five days in July, 1966.

The deplorable social and economic conditions existing in the ghetto gave rise to many of the incidents which finally led to the violence and destruction. These same conditions were also the basis for the general frustration and accumulated dissatisfaction which combined with the inciting series of events to produce the rampant disorder.

Many people pointed to the vicious cycle that entrapped Hough’s black residents — housing, jobs, and education — as the primary factor behind the frustration and bitterness so prevalent in the ghetto. Others mentioned that these causes had been compounded by poor police-community relations, a sense of impotence within the black community, inadequate welfare levels, poor recreation facilities and programs, and irregular garbage collections. Certainly, all thee factors were interrelated, and each contributed to the disorder. These pitiful social and economic conditions were perpetrated, explained and tolerated by an underlying racism — the belief that black people are inferior to white people. The latent but omnipresent racism of the community only served to push the cycle of poverty, inadequate housing and schools further downward, and served as the basis by which the tangible factors became important contributors to the decay of the community.

Inadequate Housing

I would love to live in a regular house.[29]

Much of urban life centers around housing. Location of residence often determines the opportunities for gainful employment, for education, and for many other benefits of urban life. The black community of Cleveland was subjected to a shortage of adequate housing, poor and crowded living conditions, and racial discrimination when black residents tried to move. These charges were all well documented in the Special Census of 1965, the hearings before the Civil Rights Commission in April, 1966, and the PATH report, issued in March, 1967, after six months of investigation by a group of thirty citizens.[30]

In the period-from 1950 to 1967, only 30,000 new dwelling units were constructed within the city as compared to about 150,000 units constructed in the suburbs throughout the rest of the county.[31] With only five per cent of the county’s black residents living in the suburbs, there was an increasing shortage of new housing in the city available to blacks compared to whites.[32] The existing dwellings within the city were deteriorating during this time, too. The 1960 Census showed 50,000 units within the city as substandard, and in 1966, despite the demolition of some 10,000 units, there were still about 50,000 substandard dwellings inside the city.[33] These statistics hit areas like Hough particularly hard, especially as the community became more and more segregated as whites moved out. Many people testified at the Civil Rights Commission Hearings about the deteriorated conditions in which they were forced to live, and the difficulty black residents had securing loans from any of the financial institutions to finance new construction in the blighted areas such as Hough. Thus, because of the residential patterns of the city and the unwritten rules of segregation, there weren’t many housing and dwelling opportunities for black citizens of the inner-city.

Those opportunities that did exist in Hough were considerably less than attractive. Many individuals testified at the hearings in April about the conditions of Hough’s housing. The absentee landlords rarely responded to complaints of their tenants, and because of the city’s lax methods of enforcing the housing code, conditions of squalor and total deterioration often went unnoticed and uncorrected. The testimony of the Commissioner of Housing demonstrated that the city’s housing code was not strictly enforced because of a personnel shortage as well as political pressures exerted on the city government. In areas of urban renewal, it was disclosed that the codes were never enforced because the jurisdiction for enforcement was changed to the department of urban renewal. As a result of the code practices, absentee landlords often let their property totally deteriorate and rarely made substantial improvements. Approximately 50,000 substandard dwellings stood within the city at the 1960 census, but the Commissioner of Housing disclosed that in 1965 only 299 warrants were issued by the courts that dealt with housing code violations. There were no warrants issued to landowners in the area affected by the urban renewal plans.[34]

The success of the urban renewal programs in the ghetto was virtually nonexistent. As the PATH report accurately summed up, Cleveland’s urban renewal program had been a failure in the years before the riots. The program had not added to the housing supply of the city nor had it succeeded in blocking further deterioration of the community’s dwellings. The area’s largest project, the University-Euclid project, was centered on the East Side of town, and it had planned to rehabilitate over 4,000 units in 1961. In late 1966, despite the fact that its administrative budget had been used up, the project had only rehabilitated about 600 units.

The urban renewal programs suffered from several defects, among them: inadequate planning and slow execution of plans that were made; lax enforcement of housing code in renewal areas; ineffective and often discriminatory relocation assistance to families that had to be moved during the renovation process; and lack of resident participation and consent on the goals and methods of attaining the goals of the program.[35] Research data presented at the Civil Rights Commission hearings showed that only fifteen per cent of all the families relocated in the most recent projects before 1966 went to housing to which they were referred by the relocation office. In University-Euclid, data showed that of 383 black families that were relocated, only 76 resettled in census tracts that were less than fifty per cent black. Almost half of those displaced settled in census tracts that were more than ninety per cent Negro, thus compounding the ghetto problems.[36] Earlier, other downtown urban renewal projects had dislocated many residents from their homes, but rather than smoothly assimilating into the outlying suburbs like other displaced ethnic groups, the Negroes were almost forced to move into already crowded black neighborhoods. Ghettos like Hough were the inevitable result of these urban renewal efforts.[37] Cleveland also illustrated another shortcoming of many urban renewal programs that was mentioned by Robert Weaver — the disregard for democracy which seemed to characterize many of Cleveland’s efforts. Cleveland could very well have been the city to which Weaver alluded when he wrote that in one community, some new greeting cards were circulated. On the cover, the cards read, “Urban Renewal is Good for You,” and on the inside flap the cards said, “So Shut Up.”[38]

Cleveland’s Urban Renewal Director until January, 1966, James Lister, illustrated a rather uninformed attitude toward the entire concept of urban renewal and planning in 1965 when he said, “Even if we don’t find ready builders (for a project) … just clearing the land to get rid of those slums justifies what we are doing.”[39] According to Lister, desoluation [sic] was a blessing, and his department appeared to have been guided by that principle during the time of his direction. Lister was replaced in March of 1966 by Barton Clausen, a man formerly associated with television broadcasting with no previous experience in either actual urban planning or urban renewal. The program continued along at its feeble pace until finally in January, 1967, the Department of Housing and Urban Development announced that no new funds for urban planning or renewal would be allocated to Cleveland until the present problems were solved and the entire project restructured.[40]

Even the department’s public information officials were not impressed with the department’s record over the last five or ten years. One official remarked, “We’ve had some bad failures and good successes,” while another city employee frankly admitted, “Urban renewal hasn’t been the brightest light om our horizon.”[41]

Discrimination was actively practiced against black citizens in the sale of housing in Cleveland, and so the walls of Hough became nearly impossible to scale. Many young educated Negroes testified that they were often not shown housing in white areas by realtors, and often their names were referred to black realtors by the white realtors whom they had contacted. Mr. and Mrs. Robert Crumpler related an incident to the Civil Rights Commission that was typical of the plight of many Negroes. Mr. Crumpler, a black elementary school science teacher. and his wife, a white, had sought to rent a home in Cleveland Heights, a middle class suburb on Cleveland’s East Side. After reaching verbal agreement with Hr. Crumpler to rent over the telephone, the owner talked with a present tenant and discovered that Mr. Crumpler was black. Suddenly, the lady talked again to Mr. Crumpler and explained that her child had contracted measles and so she couldn’t have a contract for several days. An hour later, the owner rented the apartment to a white Couple. As Mr. Crumpler later testified, the measles of the owner’s son were “possibly the fastest case in history.”[42]

The suburbs were virtually closed to Negro migration. Of the more than fifty municipalities surrounding the City of Cleveland, only three had allowed more than a few Negroes to live in their communities, and even in these places, the process of integration was a very slow and uneasy one. Because of this denial of housing opportunities, the demand for housing in the city by blacks was very high. The result was that Negroes often had to pay more than whites for housing of an inferior quality. Even in the placement of people by the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority, the public housing department, there was evidence of some discrimination. It was documented in the Civil Rights Commission hearings that 99% of the white tenants in public housing lived in predominantly white estates, and about 81% of the black tenants lived in three predominantly Negro projects. Occupancy statistics of public housing indicated that white tenants comprised fifty-three per cent of the total while blacks comprised about forty-seven per cent.[43]

The housing problems of the Negro in Cleveland were monumental in the years before the Hough disorders. A shortage of available dwellings, terrible living conditions that were rarely corrected, an inept urban renewal program, and widespread racial discrimination worked an even greater hardship on the residents of Hough. The ghetto became severed from the test of the community, and the living conditions there were often unbearable. The ghetto was bound to explode.

Unemployment and Underemployment

Cleveland has an ordinance which prohibits employers, employees, labor unions, and employment agencies from discriminating on the basis of race, creed, color or national origin.[44]

Unemployment and under employment are firmly entrenched in the ghetto. Unemployment of the labor force in any area can result in further problems for the society, and in the ghetto, these problems assume a much greater importance. Other conditions are present there that compound the problems of the unemployed. Similarly, underemployment has adverse effects, psychological and otherwise, on the inhabitants of the ghetto. Menial jobs with little chance for advancement, creativity, or enjoyment, are often not the answer to the problems of unemployment and as a result, underemployment often does more to reinforce the “revolution of rising expectations” than to alleviate the problem of unemployment.

Hough residents were victims of both unemployment and underemployment. In 1965, Negroes comprised about one-sixth of Cleveland’s metropolitan labor force of 885,000. Unemployment was estimated at 2.9% of the labor force in July of the same year[45] At this same time, unemployment within the city was at 7.1%, and for the black workers within the City of Cleveland, the situation was even worse, unemployment averaging about four per cent higher than the mark for the entire city. Thus, unemployment for blacks ran about three times higher than the rates for whites within the city. The Hough neighborhood showed an even higher rate of unemployment, with 13.4% of the male labor force and l7.5% of the female labor force recorded as unemployed, but the black residents of Hough hit an even lower figure, as 14.3% of the black male labor force and 19.1% of the black female labor force in Hough were unemployed during the 1965 special Census in Cleveland.[46] Unemployment among the black people of Hough was worse than their white neighbors in the ghetto and drastically worse than among even other Negroes throughout the city. However, the black resident of Hough faced other problems even when he was employed.

If he were employed in the building industry, he would have had difficulty getting good jobs and remaining continually employed because he wouldn’t have been in a trade union. In 1965, the total union membership in building trade unions was 7,786. Of this total only 55 members were black, less than one per cent of the total, despite the fact that a higher percentage of Negroes were in the industry.[47]

Cleveland’s black citizens also had difficulty securing employment in white collar jobs. In 1965, about forty per cent of employed white males had white collar jobs, while only fifteen per cent of employed black males were in jobs of this nature. On the other hand, sixty-three per cent of the black male employed labor force were in blue collar jobs, compared to only forty-nine per cent of the white males in such jobs.[48] Many government sponsored training programs were instituted in Cleveland in 1965, but most of the Negroes that were selected for these programs were taught semi-skilled professions. Even the status of trainees that completed the training program funded by the Manpower Development and Training Act indicated that the black citizens of Cleveland were coming out second best. The white trainees reported a rate of unemployment of 18.5% for all white trainees, but the figure for black unemployment out of total black trainees was 26.7%.[49]

The problem of unemployment was compounded by other factors involving black employment. The men and the women of the ghetto, when they were employed, were often relegated to the lowest and most menial positions. Even training programs found fewer of their black graduates employed than the white graduates. The black people of Hough faced great barriers in their attempts to secure gainful employment. Part of the reason they rioted was to pull down some of these barriers.

Inferior Education

Negro students as a group consistently score in the lower ranges on standardized tests, and the divergence between white and Negro academic performance increases over the child’s academic career.[50]

Inferior education is the third major component of the ghetto cycle of life. Combined with inadequate housing and unemployment, poor education helps to lock the ghetto inhabitants in their impoverished pattern of life forever. The residents of Hough saw their children receive a segregated and very inadequate education. This condition only increased the bitterness and frustration of the black community.

Cleveland’s educational system was based on the neighborhood principle — children attended schools in their own neighborhoods, the schools that had the closest geographical proximity. Residential segregation, therefore, resulted in educational segregation. In October of 1965, eighty-three per cent of all students attending public schools in Cleveland attended schools that were more than ninety-five per cent white or black, in their racial composition. About ninety-one per cent of the students attended schools with eighty per cent or more of a racial imbalance, and in elementary schools, over ninety per cent of the children attended schools with more than ninety five per cent white or black students attending them.[51] Newly constructed schools only perpetuated de facto segregation. In all but two of the twenty-seven new schools that were constructed in the few years prior to 1965, the racial imbalance was greater than ninety per cent. Black teachers were very rare in predominantly white schools — only five per cent of the teachers in the white schools were black. The reverse trend was true in predominantly black schools, and from the statistics presented by the Civil Rights Commission Staff, it was rather obvious that new teachers had been assigned partly on the basis of race. There were twenty-three Negro principals in the school system in 1965, and twenty-one of them supervised schools that were more than ninety-five per cent black. Even in the advanced enrichment programs that were offered to students with high academic potential, more than eighty per cent of the students attended schools with a racial imbalance greater than ninety-five per cent.[52]

The quality of education in the predominantly Negro sohoo1$ was inferior to that received in, the white schools. A comparison of standardized test scores showed that by the sixth grade, students in predominantly black schools were more than one grade behind their counterparts at white schools, and this difference had increased from only a half-grade difference that had been present at the first grade level. The results of the Probable Learning Rate Tests also showed that the students at predominantly black schools were learning at a slower rate than other students.[53] The dropout rates at the segregated black schools were also much higher than they were at the white schools — 14.6% of the student body per year for black schools compared to 6.5% a year for the white schools.[54]

In 1962, the Greater Cleveland Associated Federation designated a group of citizens to formulate a seven year plan for improving the city’s educational system. In April, 1963. the committee made a report of its findings and recommendations, and they focused considerable attention on the deteriorating state of the Cleveland and ghetto school districts. The PACE (Plan for Action by Citizens in Education) report called for a commitment by the entire community to upgrade the quality of the public education in the city. However, in 1965, the staff of the Civil Rights Commission was able to report. “Since publication of the PACE report. there has been little change in the system.”[55] A new school superintendent, Dr. Paul Briggs, was hired in 1964, however, and soon he announced that he intended to eliminate much of the criticism directed at the school system by improving the quality of education and increasing integration. Such progressive ideas, however, had not been very widely implemented by the spring of 1966, and the school system for the vast majority of the city’s black citizens remained inferior.

The City of Cleveland spent about one-half as much as some of the richer suburbs for the education of its students. Cleveland’s cost per pupils of $436.90 per year placed it among the very lowest districts in Cuyahoga County, and its student-teacher ratio was the highest in the county at thirty to one.[56] Thus, even within the city’s inadequately staffed and financed school district, the bulk of the black students received an inferior education. This fact was most detrimental to impoverished pockets of black life such as Hough, because in these areas, one of the only hopes of escape was a decent education. The residents of Hough did not receive even that hope.

Hough’s black residents thus experienced the classic conditions of discrimination and poverty inadequate housing, unemployment, and inferior education. Other Negroes in the rest of the city also experienced these phenomena to a lesser extent. Only in Hough were these conditions all prevalent simultaneously with a severity not experienced throughout the rest of the city. But even these classic conditions were further compounded by other adverse factors in the Hough community such as inadequate welfare levels and poor police relations. These conditions also collaborated in igniting the destruction and violence of the 1966 summer.

Inadequate Welfare — Aid to Dependent Children

… our present system of public assistance contributes materially to the tensions and social disorganization that have led to civil disorders.[57]

There were seven programs of welfare and relief that were administered by the Cuyahoga County Department of Welfare in 1966. The most costly and widespread of these programs was the Aid to Dependent Children (AOC). This relief was directed at families and children without a family head who could provide a source of income. Two-thirds of the program was federally financed, but administration of the welfare was left up to the county units.

Cuyahoga County had a total of 10,311 cases of families on ADC in 1966. About eighty-seven per cent of the persons involved in this welfare were black, and about one out of every four families in Hough were on ADC. To be eligible for payments, a family’s income could not exceed $165 a month. This standard of eligibility placed Ohio sixteenth in the nation despite Ohio’s eighth place ranking in per capita income. Other states with high per capita income, such as New York, allowed families to earn much more than $165 a month without taking them off welfare.

The standard of welfare payments for ADC was set in 1959 and had not been changed since then in spite of the rising cost of living and inflated prices.[58] Unfortunately, the county did not even meet the 1959 standards in the actual ADC payments made. Instead, in 1966, the average payment was only 76% or the established standard. Payments to a family of four on ADC remained constant during the period from 1960 to 1966, and as a result, the position of the recipients of ADC, in economic terms, had declined drastically.[59] The ADC payment to a family of four headed by a female, was only seventy-one per cent of the poverty level of existence set by the Social Security Administration in 1964. Even allowing for a food stamp bonus in which a family could receive extra food at minimal cost, the cash payment and medical allowance of the ADC program was still only eighty per cent of the Social Security poverty index.[60] Food allowance payments averaged only sixty per cent of the standard budget figure set in 1959 for “food and other” expenses. And yet, all other welfare programs administered by the county were paying higher than ninety-five per cent of their standard budgets set in 1959.[61]

Hough’s dependence on the ADC program resulted in extremely adverse effects for the area because of the inadequate welfare payments. Coupled with the extremely low payments was the problem that merchants in Hough often raised their prices on the tenth of every month, “Mother’s Day” as it was known in Hough, when ADC checks were issued. Sales at stores were strategically held at the end of every month when few of the recipients of ADC had any money, and often stores in the area required a certain amount of goods to be purchased before they would cash any ADC checks.[62]

For an additional child, the incremental payment of ADC worked out to be seventy-three cents a day. Although many persons felt that the welfare structure of Aid to Dependent Children encouraged women to have more children, it was rather dubious that women would have children merely to receive an additional seventy-three cents a day. The program did not reach many ghetto inhabitants that needed welfare and discouraged many recipients from seeking work because of the low eligibility standards. By remaining in the ghetto for extended periods of time, it was only natural for the women on ADC to have large numbers of children, for in a slum like Hough, the next day was the “unimaginable future,” and nine months was “an absurdity.”[63]

The welfare structure which prevailed in the ghetto only compounded the adverse conditions that originally led to the need for some form of welfare. The welfare that was received only added further tinder that soon ignited.

Police Practices

There evidently is a sharp difference in feeling toward the police between the Negro and white citizens of Cleveland.[64]

The attitudes of the Hough community toward the police were very apparent once disorder had erupted in the community. Latent hostility and bitterness quickly rose to the surface once the looting and vandalism began in July, and therefore, attitudes toward the police served as an important underlying cause of the rioting once it had begun. The ghetto’s feelings were justified by much evidence, but the attitudes were also affected to some extent by Hough’s own perception of the facts.

Before, during. and after the disorder had broken out in Hough, it was plain that there were not cordial relationships between the police department and the Hough neighborhood. In the spring hearings of the Civil Rights Commission, there were no witnesses from the black community that claimed the relations were good. Many witnesses related incidents of police brutality, and some complained of deficient protection in the black ghettos. The black community’s testimony was almost unanimous in its criticism of the police department. In the days before the riots, a petition to City Hall was circulated door-to-door throughout the Hough neighborhood that expressed “discontent at a seemingly biased and ineffectual Police Department.”[65] During the actual disorders, many residents of the area spoke bitterly of their disdain for the police department. A group of young residents told a reporter that most of the people in Hough were very troubled by the police attitudes, and most people in the ghetto did not have any respect or confidence in the department. one man said, “It would help if the police stopped bugging us all the time, picking up people on the streets for no reason.”[66] Lawyer Stanley Tolliver stated that there was no respect for the police in Hough because of their illicit money-making activities on the side, and Lewis G. Robinson added, “The only hoodlums Tuesday night (second night of the riots) were Mayor Locher’s blueshirted hoodlums.”[67] One unidentified nineteen-year-old told reporters that police stopped him to search him with the words, “Stand still, Nigger. Turn around. Nigger.” Then they searched him for a knife and in the process ripped some of his clothing.[68]

After the disorders had ended, there were many public utterances and proclamations by black leaders that the present relationships with the Police Department were intolerable. and the head of CORE, Baxter Hill. called for a police surveillance squad in order to “patrol the police.”[69] In the Citizens’ Panel hearings, the police were often the subject of discussion, and the bulk of the recommendations in their report centered on methods to improve police-community relations. Much testimony of police brutality and racist attitudes were presented to this committee, demonstrating with little doubt that the black community attitudes were very antagonistic toward the police.

The President’s Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders concluded that attitudes toward police had been an important factor in catalyzing the conditions of frustration into destructive action. The Commission stated that the police were symbols of white racism and white repression to many Negroes, and that often police did, in fact, express and reflect these white attitudes. “The atmosphere of hostility and cynicism is reinforced,” the Commission added, “by a widespread belief among Negroes in the existence of police brutality and in a ‘double standard’ of justice and protection — one for Negroes and one for whites.”[70] The statistics and facts of Cleveland serve to partially substantiate such feelings of the black community.

In October, 1965, the Police Department employed 2,021 people despite its budgeted authorization of more than 2,700 persons. Only 133 of the Police Department personnel were black. Of this group, only two men were above the rank of patrolman, and they both were sergeants.[71] Chief Wagner explained that the department was having great difficulty recruiting both white and black applicants, but that it was making every effort to attract qualified Negroes.

The city was divided into six districts, each with an office centrally located within its geographical boundaries, to facilitate law enforcement throughout the entire city. The Fifth District at the police network encompassed the Hough community and included about 18% of the entire city’s population. This district, however, witnessed more than a quarter of all the city’s crime. Prostitution was the largest single class of vice, and it accounted for more than one-third of the arrests in the district in the three years preceding 1966.[72] The complaints of the Hough residents were basically within three related categories. First, they believed that police were slower to respond to calls for help within their district. Secondly, the people believed that the police did not enforce the law as strictly in the predominantly black district as they did in other areas. Finally, many people complained about arrest procedures. They thought that the police were often unnecessarily brutal in making arrests, that arrests were often made for no reason, and that complaints of citizens against these abuses were not properly acknowledged.

Statistics of the police department did show that police were slower to respond to calls in the Hough district than in other areas of the city. Appendix Four shows a comparison of the time it took police to respond to calls in the Fifth District to the times for the First and Second Districts, both predominantly white in their composition. The table was compiled from random checks on each district for every day of the week. From the figures, it is clear that the response in Hough was much slower than the response for the two white districts. The Fifth District had the slowest average response in ten of the eleven categories of incidents which occurred in all districts. In the robbery category, response in the Fifth District was about four times slower than in the two white districts, and in cases of burglary and housebreaking without larceny, the response was more than twice as slow.[73] The police answered the charges of slower response by claiming that the large number of calls coupled with inadequate equipment made faster response impossible. They did not mention the possibility of reallocating some of their available resources.

The major thrust of the second complaint that the residents of Hough leveled at the Police Department was that vice offenses were not enforced as strictly in the Hough area as they were in other places. The available statistics did not substantiate this charge. Neither did they disprove it. Arrests for prostitution and gambling increased in the Fifth District in 1965 from the previous year, and police vigorously denied that there was any double standard involved in making arrests.[74] Total crime in the area had decreased, but this decrease could at least partially be explained by the decrease in population of the district as well as by strict police enforcement. Similarly, the increase in arrests of gamblers and prostitutes did not necessarily indicate a strict policy of enforcement because increases in these vices might have meant that a smaller percentage of offenders were caught. The black community, however, persisted in its belief that the law was more loosely enforced within their

district.

There were numerous occasions when Hough residents complained of brutal treatment by the police. However, both police Chief Wagner and Safety Director McCormick proudly claimed that no investigations had ever sustained any case against a member of the Police Department. They neglected to mention that the system of handling complaints that was used by the police was both archaic and ineffective. Complaints were not systematically recorded, and when complaints were received, they were handled in a rather flexible procedure by the ranking officer of the district in which the complaint was lodged. If the complaints were serious enough (as judged by the district officer) they were brought to the attention of Chief Wagner and even Director McCormick. Complaints could also be lodged through the Community Relations Board of city government, but Chief Wagner had kept his men from appearing at the board’s hearings

to answer charges that were made against them.[75]

The attitudes of some Cleveland policemen were also responsible for much of the black resentment in the ghetto. Professor John Ronayne of Fordham University, in a study of the police department for the Civil Rights Commission, concluded that some police believed “that eighty-five per cent of the crime in Cleveland is committed by Negroes although they only make up about thirty to forty per cent of the city’s population.”[76] This attitude partially explained why many black people were picked up in the Fifth District on suspicious person charges. The number of arrests made in other districts on these charges were much lower. Hough residents often complained of being arrested as “suspicious persons,” and police records indicated that a higher percentage of people in the Fifth District were arrested and later released without charge in investigations of robbery and prostitution than in the other police districts. Statistics from 1965 indicated that 999 females in the Fifth District had been arrested for investigation of prostitution, but that only 76 were formally charged with the offense. The police said that the reason for this abundance of arrests was that there was often evidence indicative of prostitution (e.g. waving at passing cars, talking to strangers, etc.) that could not have been sufficient to convict the females in courts of law. Therefore, police had liberally arrested known prostitutes and other women who were soliciting business despite the fact that they had too little evidence to charge them or convict them in order to eliminate the vice. However, it was also true that a disproportionate number of black males were arrested in the Fifth District for investigation of robbery.[77] Thus, the resentment of the black community toward the police department was justified to an extent through the departments own statistics in the areas of grievances and unnecessary arrests. Instances of police brutality were heavily disputed by the police even though testimony by area residents had frequently revealed mistreatment.

The Hough residents had Some legitimate grievances to air against abuses of policemen in their district. The established mechanisms for handling grievances and complaints were ineffective and unresponsive to the needs of the community. Resentment and bitterness toward the police force ran deeply throughout the black community. Perhaps these attitudes were some of the reasons that the department had such difficulty recruiting any more qualified Negroes. In any case, the hostility of the community toward police authority and practices served as a very real and supporting cause in the ignition and subsequent course of the Hough disorder.

Many other specific factors could be mentioned as underlying contributors to the disorder that occurred in Cleveland. Lack of recreation facilities in the ghetto, relations with white merchants, and family instability were some of these other conditions that were prevalent in Hough.

All of the deplorable conditions in Hough resulted in a pervasive frustration that was ingrained in almost every black resident. The common denominator among all the specific causes of the frustration was the factor of race, and thus, the latent racism of the community led ultimately to the ghetto’s deep frustration — a frustration that finally culminated in civil disorder.

Black Frustration

It happened because no one in Cleveland cares anything for us out here.[78]

In all the discussions with rioters throughout the disorders, one word was frequently used — frustration. The residents of Hough were frustrated in attempts to partake in the decision-making process that determined their way of life. The residents of Hough were frustrated in their efforts to secure better and decent housing. The residents of Hough were frustrated when they tried to secure gainful employment and anything but menial jobs. The residents of Hough were frustrated by their inability to improve abusive police practices. And the residents of Hough were frustrated in their efforts to leave the ghetto and improve their socio-economic standing in the community.

Much of the black community regarded the Negroes in city government as sellouts because they were so easily co-opted by the white establishment once they were elected. As a result, many of the-black citizens did not feel that there was any true representation of the black community’s interests in the city government. One woman aptly summed up the ghetto’s feelings when she told a reporter, “They’re (black elected officials) us’s when we send them, but they’re not us’s when they get there.”[79] The remark illustrated the feeling of frustration ingrained in the black citizen even in the area of political influence. Thus, the ghetto dweller found all avenues of hope through which he could win self-esteem blocked — blocked by inadequate education and job discrimination, and by a system of political power that did not respond to his needs. Lewis Go Robinson echoed these sentiments when he stated that there was “too much political expediency in the system.”[80]

The symbol of all the frustration that had built up was the ghetto itself. Hough embodied everything that the black man had been forced to accept. Its physical appearance, its way of life, its standards and mores — all reflected the frustration of the black community in its efforts to gain equality in a democracy. Because the ghetto so symbolized the despair and defeat, it was only natural that those who had

been forced into it — those whose way of life was mired in an endless downward spiral of poverty and discrimination who had little to lose — should attempt to destroy their own neighborhood. This property held them captive in the ghetto and was a manifestation of white power and supremacy. One rioter succinctly stated this attitude when he remarked, “White man own the place. Prices too high. Like to see it burn.” He later added, with a subdued chuckle, “When people get through, ain’t gonna be no Hough.”[81] Hough symbolized all that was bad for the black citizens of the nation.

It was impossible to identify one specific cause for the Hough riots. As a newspaper reporter accurately asserted at the time of the disorders, it was too late for the city to quickly remedy the problems that were responsible for the riots, “because there (was) … no one problem at which to point an accusing finger with deadly, bitter certainty.”[82] A combination of inequities and injustices which were unescapable for the vast numbers of black people who found themselves in these atrocious conditions resulted in a general malaise and frustration which was certain to finally culminate in civil disorder.

Unfortunately, the white community and leadership did not have the empathy to fully understand the situation of the black ghetto and to help alleviate its problems. White from closely knit families in middle class America could not easily comprehend the problems of blacks from broken families in the ghetto. Similarly, the black ghetto dweller had a distorted view of the world around him only because of his limited experience in it. The tragedy of such misunderstanding and frustration was the disorder that claimed human lives and resulted initially in the further polarization of the two communities. The vicious cycle also included violence and destruction.

As Kenneth Clark has pointed out, the poor have always been alienated from society. They are rejected by society because of their low social and economic standing. However, when the poor are black, as they have increasingly become in the major urban centers, “a double trauma exists.”[83] The poor black man is also shackled by the bonds of despair and frustration, the resulting evils of racial discrimination. The general frustration that evolved into destructive action emananted [sic] from deeply ingrained racist notions of the Cleveland community.

White Racism

All my life, people been calling me Nigger.[84]

Beneath the complex causes and interrelated phenomena that ignited the five days of disorder in Cleveland was an intrinsic and widespread prejudice against the black man that permeated almost every aspect of the white community.

Every available statistic substantiates the pattern of discrimination in Cleveland — the second class citizenship afforded its black population. The figures show that the black citizens of Cleveland, particularly those of Hough, were much poorer in socio-economic terms than the rest of the community. The average of a black person’s education was less than the average for whites, and this disparity was compounded by the inferior quality of education that the blacks received. Median income declined for the black people of Hough while it increased for everyone else. Family instability was more prevalent in Hough than anywhere else in the city. Although individual Negroes were occasionally accepted by the surrounding white society, racism impeded the development of the entire black community of Cleveland. Racism was the primary cause of the high incidence of residential segregation within the city as well as the ramifications of this pattern. Discrimination in employment and labor unions had occurred to a higher degree than anyone in the community wished to admit. Policemen did have different attitudes toward the blacks as a group than they did toward the whites, despite all protestations to the contrary by the Police Chief. Bigotry and prejudice combined to build almost unsurmountable walls that surrounded the Hough ghetto and stymied the advances of the entire black community.

The traditional American dream of upward mobility through rugged individualism was a sham for the black citizen of Cleveland. For other minority groups, assimilation into society has depended only on modification of their traditional cultural and behavioral patterns. The black people have not been so fortunate. Black people must also overcome the barrier of prejudice in their efforts to win full equality.

The walls of the Hough ghetto were erected by a white society with power both to confine those who had no power and to perpetuate the inherent powerlessness of that community. As Kenneth Clark explained, the ghettos that have emerged arose as “social, political, educational, and — above all — economic colonies. Their inhabitants are subject peoples, victims of the greed, cruelty, insensitivity, guilt and fear of their masters.”[85]

The people of Hough, by either their violent actions or quiet acquiescence to the destruction, rebelled against the authority that trapped them in the ghetto. They rebelled against the conditions of their existence. They rebelled against racism.

Cleveland had indeed moved toward two societies, one black, one white — very separate and very unequal. Divisive forces were neither recognized nor heeded by the community. Disorder was the ultimate consequence, and so Hough burned.

The initial impact of the violence only heightened the same divisive forces. Only time would reveal the final significance of the disorders. The new awareness in the white community of the black ghetto’s problems was not head-one by reaction to the means of destruction which had produced that new awareness. Progress hinged on the outcome of that encounter.

- Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (New York, 1968), p. 1. (Source hereafter cited as Advisory Commission). ↵

- Karl E. Taeuber and Alma F. Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (Chicago, 1965), p. 39. ↵

- Hearing before the United States Commission Rights, April 1-7, 1966, p. 100, testimony of Mr. Lyle Schaller. (Source hereafter cited as Civil Rights Commission). ↵

- Kenneth Clark, as quoted in John Skow, "Can Cleveland Escape Burning?" Saturday Evening Post, July 29, 1967, p. 39. ↵

- Kenneth B. Clark, Dark Ghetto (New York, 1965). p. 27. ↵

- Bureau of the Census, "Changes in Economic Level in Nine Neighborhoods in Cleveland: 1960 to 1965," Series P-23, No. 20, September 22, 1966, pp. 1-7. Also Series P-23, No. 21, January 23, 1967. ↵

- Robert Crater and John Russell, "Mayer Backs Jury in Senate Hearing," Cleveland Press, August 26, 1966. ↵

- Paul Welch, "A Bitter and Insistent Plague: The People on Hough Find Themselves in a Racial Trap," Life, LIX, December 24, 1965, p. 106. ↵

- Letter from Mrs. Roberta Allport, Research Department, Cuyahoga County Welfare Department, January 28, 1968. ↵

- Saul S. Friedman. "Riots, Violence and Civil Rights," National Review, XIX, August 22, 1967, p. 899. ↵

- Welch, "Insistent Plague," pp. 108-109. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Advisory Commission, p. 6. ↵

- Friedman, "Riots, Violence," p. 900. ↵

- Robert Penn Warren, Who Speaks for the Negro? (New York, 1965), p. 380. ↵

- Friedman, "Riots, Violence," p. 901. ↵

- Ibid., p. 903. ↵

- "Ice, Water and Fire," Newsweek, LXVIII, August 1, 1966, p. 18. ↵

- "And Now Cleveland," The Reporter, XXXV. August 11, 1966, p. 8. ↵

- "Report of the Panel Hearings on the Superior and Hough Disturbances," pp. 9-10. ↵

- Cleveland Press, June 24, 1966. ↵

- Bob Modic, "Vast Projects to Keep Idle City Youths Busy," Cleveland Press, June 25, 1966. ↵

- Cleveland Press, July 2, 1966. ↵

- Paul Lilley, "Mayor Meets With Negroes." Cleveland Press. July 5, 1966. ↵

- Cleveland Press, July 25, 1967. ↵

- Donald Sabath, "Hough Slum Battle Still at Standstill," Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 26, 1966. ↵

- In an interview, Locher claimed that he did not see the leaders because they had not gone through the prerequisite "proper channels" to see him. He also justified the later arrests on the grounds that each offender was later convicted. ↵

- Skow, "Can Cleveland?," p. 42. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 31. Testimony of Mrs. Hattie Mae Dugan. ↵

- PATH -- Plan of Action for Tomorrow's Housing. It was a group of thirty citizens formed by the Greater Cleveland Associated Federation in September. 1966to study housing problems of Cleveland. ↵

- PATH Citizens Advisory Committee. "Plan of Action for Tomorrow's Housing in Greater Cleveland," March, 1967, p. 12. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 206. Testimony of Mr. Townsend. ↵

- "PATH Report," p. 13. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission. p. 131. Testimony of Mr. Sheboy. ↵

- "PATH Report," pp. 19-20. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 175. Testimony of Mr. Wolf. ↵

- Doris O'Donnell, "Hough Fuse Has Sputtered for Years," Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 27, 1966. ↵

- Robert G. Weaver, The Urban Complex: Human Values in Urban Life (Garden City, 1964), p. 82. ↵

- Charles Abrams, The City is the Frontier (New York, 1965), p. 150. ↵

- "PATH Report," p. 22. ↵

- Interviews with the public information officials in Cleveland, January 26, 1968. Names withheld upon request. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission. p.199. Testimony of Mr. Robert Crumpler. ↵

- Ibid., p. 157. Staff research. ↵

- Ibid., p. 792. Staff research. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 784-786. ↵

- Bureau of the Census, Series P-23, No. 20, p. 5. Also, Series P-23, No. 21, p. 14. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, pp. 786-788. ↵

- Ibid., p. 794. ↵

- Ibid., p. 804. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 755. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 750-752. Staff reports. ↵

- Ibid., ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 755. ↵

- Ibid., p. 756. ↵

- Ibid., p. 758. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Advisory Commission, p. 457. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 745. Staff report. ↵

- Ibid, p. 744. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., p. 749. ↵

- Ibid., p. 253. Testimony of panel of women on ADC. ↵

- Skow, "Can Cleveland?," p. 46. ↵

- Professor John Ronayne, report in Civil Rights Commission, p.838. ↵

- Cleveland Press, July 22, 1966. ↵

- Pat Royse, Hough's Looters Offer 'Bargains'." Cleveland Press. July 20, 1966. ↵

- Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 25, 1966. ↵

- Pat Royse. "Niles Hurled Fire Bomb, Tells Why." Cleveland Press. July 23, 1966. ↵

- Cleveland Press, August 26, 1966. ↵

- Advisory Commission, p. 11. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 825. ↵

- Ibid., p. 826. ↵

- Ibid., p. 827. ↵

- Civil Rights Commission, p. 839, Report by Professor Ronayne. ↵