Main Body

The Last Chapter

Elizabeth J. Hauser

“Blessed the Land That Knoweth Its Prophets Before They Die”

Mr. JOHNSON’s health was seriously impaired when the referendum election on the Schmidt grant was held in August 1909, and while the beginning of his illness doubtless dates from a much earlier period he himself regarded this as the time of the fatal break. Yet he went through his fall campaign with much of the vigor, the fire and the good humor that had always characterized his work.

On election night when the returns showed beyond a doubt that he had been defeated he alone of the devoted group of men and women gathered at the City Hall was philosophical and brave and calm. For men who were to weep unashamed, no matter where they happened to be on the day their leader died, made no effort to conceal their emotions that night. Some of them swore, some of them cried, some of them became ill. Only the mayor was very still and very gentle and “sorry for the boys.”

When it was known that he had been returned as city solicitor Mr. Baker came and stood beside his chief and gripped his hand and said in a voice tense with suppressed feeling, “I don’t know how I can do it.” Without a second’s hesitation came the answer, “Do it? Of course you can do it. You’ve got to do it. The people want you.”

The mayor insisted upon remaining in his office until early morning and when the last returns were in and he knew that four out of five of his candidates for the quadrennial board of appraisement had been elected, he construed this as an endorsement of the taxation principles on which the campaign had been fought.

He had trained his spirit never to know defeat and it harked back now, all unconsciously no doubt, to the lesson of the Noah’s Ark incident of his childhood, and there were “two left anyhow.”

When he relinquished his office to his successor, January 1, 1920, Mr. Johnson said, “I have served the people of Cleveland for nearly nine years. I have had more of misfortune in those nine years than in any other period of my life. As that is true, it is also true that I have had more of joy. In those nine years I have given the biggest and best part of me. I have served the people of Cleveland the best I knew how.”

Almost immediately after this he went to New York for medical treatment, remaining there until February 6, when he returned to Cleveland. He spent five weeks at home all of that time under the care of a trained nurse. On the thirteenth of March he went back to New York, his mind fully made up to go abroad. He was no better; his physician’s prognosis was unfavorable, he was slowly losing strength and for hours each day was the victim of severe pain. But he ceased consulting physicians, dismissed his nurse and proceeded with the arrangements for this voyage. By some supreme act of will he had resumed the mastery of himself.

One who was observing him closely at this time wrote to a friend, “A most remarkable thing has happened.

Tom seems to have struck rock bottom and then to have lifted himself by his own boot-straps out of the depression caused by his illness. His spirit is in complete ascendancy over his body. He is going to Europe. Nothing can stop him.”

On March 23, in company of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Fels, Mr. Johnson sailed on the Mauretania for London. He seemed reasonably well and enjoyed the voyage. Arriving in London he was met at Paddington station by a reporter, but he consistently stuck to the policy he had adopted upon going out of public office – that of refusing to be interviewed by the newspapers. Mr. Johnson had several rules of personal conduct from which he seldom swerved. One of these was never to speak at a meeting or gathering of any kind at which an admission fee was charged, and another was never to stop with friends in their homes, but always to put up at a hotel. By some magic Mr. and Mrs. Fels persuaded him to depart from this last named rule and be their guest during his stay in London.

On April 11, the United Committee for the Taxation of Land Values gave Mr. Johnson a dinner at the Trocadero, one of London’s big restaurants. His address on that occasion was a fine one, at least half of it being devoted to an appreciation of the character of Mrs. Fels, who was, he said, half of her husband’s work, giving to it not the mere old-fashioned inspiration of the heart, but thought.

Just as he had insisted upon going to England so Mr. Johnson now insisted upon a trip to the continent. Fearing that the contemplated journey might prove too fatiguing friends tried to dissuade him but in vain. He was determined to go, so Mrs. Fels and John Paul, editor of Land Values and, next to Mrs. Fels, the closest friend Mr. Johnson made in Great Britain, accompanied him. They made a ten days’ tour visiting Paris, Rouen, Brussels, Cologne and Frankfort. The change stimulated Mr. Johnson wonderfully. Following this trip Mr. Fels and Mr. Paul joined Mr. Johnson in a few days’ visit to Glasgow, Belfast and Dublin. A reception was given them in Glasgow which afforded Mr. Johnson an opportunity of meeting many of the friends whom he had for years desired to know personally. He was especially attracted to those who had been friends of Henry George. “He suffered a great deal of pain at times, indeed almost constantly,” writes John Paul, “but he was cheerful and enthusiastic over the evidence he witnessed on every hand here of the progress of the ideas and the policy he himself had done so much to promote in the United States.”

On April twenty-seventh, the night the vote on the Budget was taken, a dinner was given to Mr. Johnson at the House of Parliament. He tells about this dinner in a speech in New York a month later, but fails to mention what an English correspondent tells us that “on this occasion all factions and conflicting opinions were harmonized, Mr. Johnson being the reconciling spirit. Josiah Wedgewood, M. P., presided, and speeches were made by Redmond, the hero of the Budget fight, Keir Hardie, T. P. O’Connor, Charles work, giving to it not the mere old-fashioned inspiration of the heart, but thought.

Just as he had insisted upon going to England so Mr. Johnson now insisted upon a trip to the continent. Fearing that the contemplated journey might prove too fatiguing friends tried to dissuade him but in vain. He was determined to go, so Mrs. Fels and John Paul, editor of Land Values and, next to Mrs. Fels, the closest friend Mr. Johnson made in Great Britain, accompanied him. They made a ten days’ tour visiting Paris, Rouen, Brussels, Cologne and Frankfort. The change stimulated Mr. Johnson wonderfully. Following this trip Mr. Fels and Mr. Paul joined Mr. Johnson in a few days’ visit to Glasgow, Belfast and Dublin. A reception was given them in Glasgow which afforded Mr. Johnson an opportunity of meeting many of the friends whom he had for years desired to know personally. He was especially attracted to those who had been friends of Henry George. “He suffered a great deal of pain at times, indeed almost constantly,” writes John Paul, “but he was cheerful and enthusiastic over the evidence he witnessed on every hand here of the progress of the ideas and the policy he himself had done so much to promote in the United States.”

On April twenty-seventh, the night the vote on the Budget was taken, a dinner was given to Mr. Johnson at the House of Parliament. He tells about this dinner in a speech in New York a month later, but fails to mention what an English correspondent tells us that “on this occasion all factions and conflicting opinions were harmonized, Mr. Johnson being the reconciling spirit. Josiah Wedgewood, M. P., presided, and speeches were made by Redmond, the hero of the Budget fight, Keir Hardie, T. P. O’Connor, Charles Trevelyan and Joseph Fels. Mr. Johnson’s own speech was of the things nearest his heart. He talked but little of his work in Cleveland, dwelling rather on the outlook for the final triumph of truth and justice, and expressing his own profound faith in democracy. On the thirtieth of April he departed for America, leaving behind him many new friends and a broadening of spirit to the single tax movement in England.”

Mr. Johnson returned to New York on the Mauretania, arriving May 5. That he had benefited by his six weeks’ holiday was with him a hope rather than a belief, but he was full of enthusiasm for the people’s cause. “A political revolution is going on all over the world,” he said,” and the next fifteen years are going to show great progress. I’d like to live to see it and I almost thing I have an even chance.”

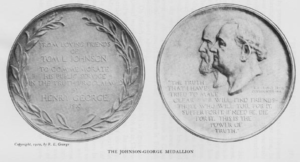

For months a self-constituted committee composed of August Lewis, Bolton Hall, Joseph Fels, Lincoln Steffens, Frederic C. Howe and Daniel Kiefer, representing thousands of Mr. Johnson’s friends, had been importuning him to permit a demonstration in his honor. They now refused to be put off longer and Mr. Johnson gave a reluctant consent to the public reception and dinner which took place at the Hotel Astor in New York City, the evening of May 31, 1910. The interval between his return from England and the time of the dinner he spent in Cleveland. The special feature of the testimonial banquet was the presentation to Mr. Johnson of a bronze medallion bearing the faces of Henry George and Tom L. Johnson in bas-relief – the work of Richard George, the sculptor and son of Henry George. Frederic C. Leubuscher, president of the Manhattan Single Tax Club, presided and addresses were made by Herbert S. Bigelow of Cincinnati; Henry George, Jr., and John DeWitt Warner of New York; Louis F. Post of Chicago; Newton D. Baker and Edmund Vance Cooke of Cleveland.

As Mr. Johnson ate nothing he must have found the long dinner a tedious ordeal. It was nearly midnight when he was called upon to respond to the addresses which had been made in his honor. He spoke briefly, saying, in part:

“The friendly words that I have been listening to tonight might be more appropriate at a later time – when the struggle for me is closed. They are pleasant to hear, but it does not seem just fitting while I am still with you. The bronze medallion, too, in which I am associated with Henry George, seems more appropriate for that later time. I said to my friends when they first suggested this testimonial, that it seemed to me like a tribute to one who had completed his work, who had finished the game; but some of my friends said I was so near the end of the struggle that we might overlook the seeming inappropriateness. I don’t believe we are at the end of the struggle. I don’t believe we have been in our last fight together. But if I am mistaken I have no regrets – only that I might have been stronger, more powerful, more nearly deserving of the things that have been said about me to-night, for no man can deserve all those nice things * * * Since my return I have often been asked, “Did the trip improve your health?” I don’t care whether it did or not. If by taking it I shortened my life by many years I should never regret that trip, for I met over there a set of men and women who have kept the fires burning all these years, who have never failed, and who have never compromised the truth. I would have made that trip to have me one of those men – John Paul. * * * It was my good fortune to meet and know this man in Great Britain, who, with Mr. Fels, has done so much for bring our movement to the center of the stage.

“One night John Paul said a suggestive thing. It was a sort of a fable, a dream – I don’t know what he called it; but it had been ringing in my ears every since and I am going to try to tell if to you. * * * John Paul said there was a certain river and that many human beings were in it, struggling to get to the shore. Some succeeded, some were pulled ashore by kind-hearted people on the banks. But many were carried down the stream and drowned. It is no doubt a wise thing, it is noble that under those conditions charitable people devote themselves to helping the victims out of the water. But John Paul said it would be better if some of those kindly people on the shore engaged in rescue work, would go up the stream and find out who was pushing the people into it. I could not help but follow that thought. We single taxers, while ready to help pull the struggling ones out, feel something urging us up the river to see who is pushing the people into the river to drown.

“It is in this way that I would answer those who ask us to help the poor. Let us help them, that they may at the last fight the battle of Privilege with more strength and courage; but let us never lose sight of our mission up the river to see who is pushing the people in. * * *

“In London I found that they understood me. I did not know whether they would understand me or not, but they looked on me as one who had accomplished something – and I was a friend of Henry George. They understood that; and they loved me as you do, and of course that made me very happy. In Scotland, at Glasgow, at Number Thirteen Dundas street, they gave me a banquet, not at two dollars and a half a plate, but at ‘ninepence a skull.’ * * * Probably the most enjoyable part of my trip was the dinner that took place under the House of commons in Westminster the night the Budget was passed. It was attended by radicals in the Liberal party in Parliament, but Irish members and by Labor members. During the banquet we went upstairs while the Budget vote was taken, and then came back for our speeches. When we broke up it was to go again to the House of Commons to hear the discussion of the Verney resolution; our resolution, we single taxers could say, for it declared for our principles. * * * It was carried by forty-three majority.

“We of the United States are interested in that struggle over there, not as outsiders but as insiders. * * * The English fight seems to us a fight where we are making the biggest headway. But everywhere, all over the world, our cause is moving, so that those of us who twenty-five years ago thought it far off, have now the good fortune of seeing the realization of our dreams. Privilege has been caught, exposed; and there is but one way to putting it down, and that is by the doctrine of Henry George. Abolish Privilege! Give the people who make the wealth of the world an opportunity to enjoy it.

“And now I come back from England and am invited to this gathering. I find here that same love and affection that I found abroad, that I have found in Cleveland. But I am not taking it as a personal compliment. I am but an instrument, I am but an agent in promoting that greater love, that love of big things, that love of justice which at last must win the world.”

About the middle of June Mr. Johnson went to Siasconset on Nantucket Island to spend the summer. Here he remained, except for two or three days spent in New York on business, until late in August. He made a friend of every man, woman and child with whom he came in contact. Nearly every man in the village was soon known to him – from the rich owners of the cranberry meadows to the casual doer of odd jobs. The engineer on the little steam railroad, the fisherman, the sail and tent maker, the house painter, the carpenter, the dairyman, the butcher, the store keeper, the lawyer who came up from Boston for week ends, the actor who spends his summers in “Sconset” – he knew them all and liked them all and they all liked him. Declining physical strength did not seem to lessen the charm of manner which gave him such a hold on the minds and hearts of all who came his way.

The books on advanced mathematics, the games of chess, which he had employed at an earlier period of his illness to divert his mind were superseded now by poetry and fiction. He became very fond of several of Kipling’s poems and these were read and re-read to him. He frequently quoted snatches of poems he had committed to memory years before. His enjoyment of Kipling’s jungle stories was like the enjoyment of a child with a well-developed imagination. He delighted in the romances of Sir Walter Scott and every character in the story he was reading became to him a living person for the time being. He looked over the newspaper clippings which were sent him regularly from Cleveland and read a New York paper daily, but rather as a duty than otherwise.

He enjoyed the wonderful sunsets over the Nantucket moors, and on the “longest day in the year” arose at three o’clock in the morning to go out, accompanied by his attendant, James Tyler, to see the sun rise over the ocean. The flowers and the birds of the island interested him.

He was on a little spot of earth at last where there were more jobs than men to do them, where health was the rule and where there was no poverty, where the jail had not been occupied within the memory of several generations, where there was one church at the service of all denominations, where by means of the yearly town meeting the people ruled. It was a good place for recreation for a man of Mr. Johnson’s convictions.

His health improved somewhat under the stimulus of outdoor life, thought he continued to suffer pains and was being gradually forced to a more and more restricted diet. Upon the advice of his physician he had given up smoking months before and he never resumed it. Though he had been an inveterate smoker for years no word of complaint on this account, nor, as one by one he was obliged to give up the things he liked to eat, escaped him then or afterwards. For long weeks before his death his diet of milk was varied only by an occasional egg or a few raw oysters. One of his attendants, seeing his suffering in spite of all this precaution, was moved to remark, “I wish I could bear it for you.” He summoned a smile and answered with a bit of ever ready philosophy, “No Tomlinson in this.” There was indeed no Tomlinson in him.

Mr. Johnson returned to Cleveland August 28, and on that day decided to give a favorable reply to the publishers of Hampton’s Magazinem, who were urging him to write for them a story of his Cleveland fight.

He went to New York the following week, arriving on Monday, September 5, Labor Day. “I don’t like Labor Day,” he said, “except as a holiday. The parades of working men seem to proclaim a difference between them and the rest of us which ought not to exist. It hurts me.”

Mr. Johnson devoted a week or more to dictating a magazine article on the Cleveland movement and from this developed the plan to have him tell his whole story. He had this in mind when he returned again to Cleveland, October 8. The evening of the eleventh he paid a brief visit to the Democratic headquarters. Commenting on this, the Plain Dealersaid, “When Tom L. Johnson walked into Weber’s Hall last night the ceiling did not go up because the floor above held it down.” He spoke but a few sentences, concluding with this characteristic one: “While we are building this city on a hill let us never forget the one necessity – that we must serve success.”

The next few weeks were the most painful of Mr. Johnson’s illness. He was not able to proceed with his writing for some time, thought he had his secretary at his house daily and attended to his mail as usual and to various matters of business.

Regardless of the effort it cost he insisted upon going to a tent meeting at which Governor Harmon and others were speaking the evening of November 1. He was not expected. This is the way a local newspaper described the event: “For a second only there was a hush. Men who had followed Mr. Johnson for years with exceeding devotion leaned forward to make certain their eyes did not deceive them. Then as the former mayor mounted the platform there was a demonstration such as is seldom seen at any time. As the governor and Mr. Johnson clasped hands the tent fairly rocked with applause. Almost the entire crowd rose to its feet to cheer. Among portions of the crowd the cheering nearly approached a frenzy. In the moment or two that the former mayor spoke he showed his old time vigor. The tent, the crowd and the flood of recollections seemingly inspired him.”

Governor Harmon said that night what he afterwards repeated in substance to Mr. Johnson in a letter: “The demonstration we have just witnessed has stirred me to the depths of my soul. I can only say that if at any time after my service as governor has expired and I appear before a body of citizens of my State and there, without the powers of office, without the possibility of bestowing favors, I shall receive such a testimonial as you to-night have given your old fighting leader, I will consider that life certainly has been well worth living.”

On November 7, Mr. Johnson voted early and busied himself for the remainder of the day much as he had been wont to do in the days of his strength, receiving election returns at his apartment in the Knickerbocker in the evening. The next day he commenced to write his story. He did his last work on it March 14, 1911, the day before he was attacked but the acute illness which was terminate in death.

Mr. Johnson left Cleveland but once after he returned in October and that was to attend a meeting of the Fels Fund Commission in New York in November. Louis F. Post” account of Mr. Johnson” participation in that meeting, written especially for this story, follows:

“To friends who had not seen Mr. Johnson since the days of his health and strength his wasted appearance was discouraging. But to me the contrast was not with his days of health. It was with periods in the course of his illness, and I thought the signs were hopeful. In no respect were they more manifestly so than in the clearness of perception, and the responsibility and directness of utterance, with which he participated in the deliberations of the Commission. Her he was altogether, except in vim, at his wisest and best.

“We met him in Cleveland, November 17, 1910. Those who gathered there were Daniel Kiefer (chairman of the Fels Fund), Fenton Lawson of Cincinnati, Doctor Wm. P. Hill of St. Louis, W. S. U’Ren and W. G. Eggleston of Oregon, George A. Briggs (one of the commission) of Indiana, myself of Chicago, and James W. Bucklin of Colorado. A loyal friend of Tom L. Johnson’s for twenty years, Bucklin was formerly a state senator of Colorado and a distinguished one; he has long been a leader in the Henry George movement; he was an attendant at the first single tax conference, in New York, and at the second, in Chicago; and he was the father of the “Bucklin Bill” in Colorado (a single tax amendment) and of the Grand Junction plan of commission government. Mr. Johnson personally conducted the party – which A. B. du Pont and Peter Witt had then joined for the purpose, — through the du Pont subway. He did it with almost all the enthusiasm of his days of intensest interest in mechanical inventions.

“On the railroad train that night he gathered us into his stateroom, as many of us at a time as it would hold (as James Tyler can testify), for he wanted the companionship and the conversation. He said very little, but he listened with manifest interest; and what he did say showed his unabated hunger for news and thought about the cause that had won his lifelong devotion nearly thirty year before.

“Oregon had just voted upon the county-option-tax amendment, now in force in that State and which, thanks in part to the Fels Fund, is to be utilized next year for a single tax campaign in every county. This measure had been proposed by Thomas G. Shearman as early as 1888, and had been then embraced and always afterward advocated by George and Johnson as the best means for promoting the single tax cause in this country. The result of the Oregon vote was not yet known, but Mr. U’Ren’s account of the campaign, which had been financed largely by the Fels Fund, was particularly interesting to Mr. Johnson. All the more, perhaps, because the introduction through friendly channels into the Oregon campaign of two nominally friendly but (under the local circumstances at that time) really inimical amendments, must have reminded him of a kind of Big Business method of opposition which he had encountered in his Ohio contests with Privilege. It was probably in part an identification in his mind of these subtle tactics in the two States as the same in origin that caused him to make the only speech I heard him make at the public meeting of the Fels Fund two or three days afterwards. His sustained interest in the result of the Oregon election on the county option tax amendment may be inferred from his message to Bucklin and me on our way home through Cleveland. Having heard in New York, as we all had, that the amendment had been defeated, but learning from Edward W. Doty on returning to Cleveland that there were vague newspaper reports to the contrary, he sent Arthur Fuller down to our train as it passed through Cleveland later than his own, to tell us what he had learned from Mr. Doty and to ask what we know about it. We knew nothing then, but his news was soon confirmed. The county option tax amendment had carried. It was the other two that had been defeated.

“In committee consultations at his rooms in the Prince George Hotel after our arrival in New York, Mr. Johnson had little to say; but his mind was alert, and whenever he did say anything he went directly to the point and without irritation or personal feeling. In all our twenty-five years of cooperation in the same cause I never knew him to be irritable in conference or public speech, nor to be moved by personal animus, and in the Fels Fund conference he was in those respects his old-time self.

“When he spoke at the public meeting of the Fels Fund, in the rooms of the Liberal Club, he did so because matters had taken a shape which in his judgment precluded his remaining silent. He recognized obstructive influences of the same character and apparent origin as some he had encountered in his nine years’ fight against Privilege in Ohio. It was not a pleasant task for him to speak of this, but as he saw the matter it was his task if anyone’s, and he did not shirk. There was no unkindness toward individuals, either in what he said or in his way of saying it. He made no accusation of bad faith against anyone immediately concerned. His suggestions, on the contrary, were of good faith played upon from outside. Nor, on the other hand, was there any weak holding back of facts he thought his associates ought to know. He spoke deliberately, frankly, and without any spirit of personal unfriendliness toward anybody, just as in public speaking he had been accustomed to do; yet with the characteristic force and clearness of statement which never left anyone in doubt of what he meant. The parallels he drew, and which were of the substance of his speech, were to the effect that whenever he had encountered the outlying influence he mentioned, it came in the form of a proposal of what he described as “something different, just a little different,” from the movement it seemed to him designed to obstruct or divert.

“Those who saw Tom L. Johnson as he made that speech, having known him before his illness and seeing him then for the first time since his health had broken, thought of him reasonably enough as of one whose physical strength had hopelessly gone but no one who had ever known him well, could have heard him then without realizing that the man himself was there in all his mental and moral vigor. Had I closed my eyes so as to shut out the emaciated body, and but listened to the voice and followed the thought, I think he would have seemed unchanged to me. In that speech I recognized as of old the vigor of voice and thought and phrase and sense of responsibility, of the same Tom L. Johnson who, coming over to Henry George in the early eighties, followed him until death, and then good-humoredly but relentlessly, regardless of friends, fearless of foes, irrespective of fortune and of victory or defeat, took the lead in fighting Privilege in its varied moods, from subtle to ferocious, for nine memorable years in Ohio.”

On January 6, 1922, Mr. Fels and Mr. Kiefer visited Cleveland as one of the points on their Western tour in the interests of the single tax propaganda. A public meeting was held in the Chamber of Commerce auditorium in the evening. Dr. Cooley presided and Mr. Fels, Dr. Eggleston or Oregon, Newton D. Baker and Mr. Johnson were the speakers. And so it happened that Mr. Johnson’s last participation in a public meeting was in behalf of the cause so near his heart. The hall was crowded and here in the very citadel of his old time enemy he received such an ovation as could not but gladden the heart of anyone. As he looked at the cheering crowd before him he said, ” This does not look like the old tent, but it sounds like it.” He spoke simply and directly as usual, and eloquently as he always did when the single tax was his theme. His voice was clear and distinct with a fullness of tone that had been absent for a long time. His closest friends might well have been deceived by his apparent strength, and those who knew that this was probably the last time he would make a speech rejoiced exceedingly in the nobility of the sentiments he enunciated that night and in the power manifested in their utterance.

On February 6, owing to contagious illness in his own family, Mr. Johnson was ordered by his physician to leave the family apartment in the Knickerbocker until all danger of infection was past. He therefore moved to Whitehall, an apartment hotel on the edge of one of Cleveland’s most beautiful parks. He was suffering less at this time, the peritonitis which was said to be the cause of his pain having evidently subsided.

Now, for the first time, he was under the constant care of a physician and the daily visits of his doctor, to whom he became greatly attached, added greatly to his comfort.

His interest in current happenings revived. He watched the newspapers for every bit of political news, especially that which had to do with the State legislature at Columbus. He looked forward with eagerness to the week-end visits of Senator Stockwell, who brought him details of activities which he could not get from the press. Magazine articles on social and political questions interested him as they never had done before. Book after book, short stories without number were read to him, and in the very last days Ernest Crosby’s poems pleased him most of all. His correspondence with friends in Great Britain was one of his diversions, his interest in British politics never abating.

On March eleventh Mr. Johnson attended as a guest the annual meeting of the Nisi Prius Club, which is to Cleveland what the Gridiron Club is to Washington. Its membership is composed of the leading lawyers of the city. Mr. Johnson went down to the Hollenden hotel early in the day and took a room, where he rested until the time for the programme following the dinner arrived, and then he went to the banquet hall in another part of the hotel to enjoy the fun. His three closest friends, the men who were with him almost daily during the last two months of his life and who had been associated with him so intimately and for so long, A. B. du Pont, Newton Baker and Billy Stage, were there, but this was not an assemblage of Mr. Johnson’s followers. It was a gathering of representatives of the privileged interests of the community. Men who had fought Mr. Johnson in the Chamber of Commerce, on the stump, in court, through the newspapers and on Cleveland’s streets made up the majority of that gathering. Yet with hardly an exception every man present shook hands with Mr. Johnson that night and expressed his good will. Perhaps they understood, as they saw him now, so sweet of spirit, so serene, so far removed from the influences of human passion and worldly strife, that after all he never had fought them, that the war he had waged with such relentless power had been directed not against individuals, but against “a wrong social order,” an order which makes victims no less of the masters than of the slaves. Perhaps they had a glimmer of that larger understanding which had distinguished Mr. Johnson for so many years. He returned to his apartment at Whitehall the next morning literally radiant with happiness. Once more and for the last time his body had been subjugated to his all but invincible will.

He was attacked by acute nephritis the night of March 14, and though he had subsequent periods of rallying death was galloping towards him now and he knew it. His anxiety was not that it was approaching so fast, but that it might be too long delayed. He was at peace with the world. If it still held enemies for him he did not know it. He had no regrets, for he had no hates. He had fought the good fight, he had done a day’s work, and he was very tired. This extreme exhaustion mercifully passed some hours before he became unconscious. A night and a day of unconsciousness preceded the end. He emerged from it once only long enough to say with a smile and a sigh, “It’s all right. I’m so happy.” Heart action and respiration ceased at the same instant at thirteen minutes before nine o’clock the evening of April 10, 1911.

The simplest of funeral rites were performed by his friends Harris R. Cooley and Herbert S. Bigelow two days later. “Two hundred thousand persons saw Tom L. Johnson’s last journey through Cleveland,” said the Cleveland Leader. “The heart of the city stopped for two hours while the simple cortege passed through the lines of silent, grief stricken men and women on its way from the Knickerbocker apartments to the Union station. * * * Flags were at half mast, buildings were decorated with crepe and pictures of the former mayor edged with mourning were displayed in most of the windows along the streets traversed by the procession. Public buildings and the Chamber of Commerce were closed. * * * Men, women and children from every walk of life comprised the vast assemblage who came to bid their former mayor a last farewell. That his friends were legion was evidenced by the respectful lifting of hats by all who were close to the passing cortege. It was not alone the women who wept. Tears flowed down the cheeks of many men who made no effort to wipe them away, but gazed with streaming eyes on the carriage containing their friend.”

The next day all that was mortal of Tom L. Johnson was laid in a grave in Greenwood, Brooklyn, beside that of his master teacher, Henry George.