Main Body

Chapter XVIII. Supreme Court Blocks Progress

The new city government went into operation May 4, 1903. That the administrative department was not to be impaired by the abolition of the federal plan which had placed the chief responsibility upon the mayor has been shown; but what about the legislative department? Here the code contained provisions so ridiculously absurd that one would be disposed to laugh at them if he could forget for a moment the menace to democratic institutions exhibited in this joint action of Senator Hanna and “Boss” Cox in framing a code expressly intended to strike at a person – in this instance the person happening to be myself.

The code was so fixed that the mayor could not appoint the board of public safety without the assent of two-thirds of the council. In case the mayor and the council should not agree the governor of the State was empowered to make the appointment. The code abolished the excellent feature of the federal plan which permitted the mayor to participate in all debates in council and department heads to participate in debate relating to their respective departments. There is not a shadow of doubt that the whole thing had been carefully planned to minimize my power. Out of a councilmanic body numbering thirty-two we now had twenty-three members who were committed to our civic programme and one of the first things the majority did was to restore the prerogative of the mayor and the department heads to participate in discussions in the council. This they were able to do for by some curious oversight the code-makers had empowered council to invite non-members to address them. Our friends defeated this piece of petty politics by making a standing rule of council extending an invitation to the mayor and to the heads of the various departments to address the meetings of council whenever they desired to do so.

If the reflections I have here indulged in on the matter of the arbitrary rulings of the new code seem bitter my address to the council on the occasion of inaugurating the new city government did not in the slightest degree question the wisdom or the integrity of the legislative body which had imposed this code upon us. Instead I said it was not for us to quarrel with the tools that had been placed in our hands, that what was required of us and what we must render was the best workmanship in all respects that the circumstances permitted. I ventured the prediction that the officials of Cleveland would prove equal to the delicate and difficult task before them. “Working harmoniously together,” I said, “without regard to party, with malice toward no man and injustice to no interest, but in response to a lively spirit of fair play to all, whether rich or poor, I believe that the members of this new city government will overcome every obstacle, those that are designedly thrown in our way as well as those that naturally arise, and so triumphantly achieve the beneficent results they have been elected to secure. . . .What greater honor could any of us desire? What object could there be more worthy of any man’s ambition than to succeed in giving strength and tone and exalted character to the municipality of which he is a citizen? to succeed in effectively cooperating in the work of establishing in his own city municipal self-government upon the basis of equal justice, and thereby setting an example of practical democracy to the civilized world?”

That was what I wanted to do for Cleveland – just that. It seemed the natural things, the right things for any mayor, for any citizen to desire for his city. But I was accused of wanting to do almost everything but the one thing that I did want to do, and from every motive, except the one that really prompted me.

Of course all this outside interference, this “guardian angel business,” as one of the newspapers styled it, strengthened us in our fight for home rule. If a movement is really based upon a principle of right, upon a fundamental truth, nothing injures it. Its progress may be checked but it cannot be permanently stayed. Its enemies aid it in the long run.

As soon as our new form of government was in operation and the supreme court injunction against us raised we went ahead with our street railroad plans. The second step towards low fare was taken May 4, 1902, the day on which the new municipal form of government went into effect, when eleven low fare ordinances were introduced in council. On July 18 bids were opened, only two being received, one for a cross-town line on Denison avenue, an isolated route on the west side and having no connection with the down town district, from Albert Green, representing J. B. Joefgen’s successors; the other for a line on Seneca street from J. B. Zmunt. On September 9 the grant for the Denison avenue lines was made to Green. It will be remembered that a cash deposit of ten thousand dollars was now required with each bid. A few minutes after council had made the grant to Green a councilman rushed in with an armful of revocations, but it was too late. The ordinance had been passed. The Cleveland Electric Railway Company claimed a majority of consents and was asking for an extension to their lines through Denison avenue. They said they had the consents, but weren’t ready to file them. They never did file them and on September 4 the board of public service denied their application and granted that of the three-cent-fare bidder. Council confirmed this unanimously and on September 9, the requisite number of consents having been filed, made the grant to Green as already stated. Commenting on this the Cleveland Plain Dealer said, “Unless blocked by the courts there can now be no obstacle to the immediate fulfillment of at least a part of the original issue with which Mr. Johnson went before the people in his campaign.” I was not quite so sanguine and when interviewed merely said that the three-cent lines would be in operation long before those who were opposed to it were ready for it. I knew we needn’t expect Privilege to lie down until it was whipped to a finish and that hadn’t been accomplished yet, but a good deal.

Ground was broken for the Denison avenue lines September 23 and then the enemy got busier than ever. Every one of the property owners’ signatures on the consents was scrutinized by the courts and fought over like the signature to a contested will. Every fly speck that might possibly offer an excuse for a law suit was examined. A mile of the road was completed and the work was going on when it was stopped by an injunction, a few days after the fall election, that is on November 12. The hearing on the injunction was first set for November 16, then postponed to the 30th and so it dragged along. The company had expended thirty thousand dollars on twenty-five thousand dollars on the construction of the line and was under bond for twenty-five thousand to complete the work. Injunctions multiplied so rapidly and checked the progress of construction so effectually that the enterprise was often referred to as the three-cent-fare railroad buried in the mud. It took time and more patience than in my earlier life I would have supposed existed in the whole world to put that venture through.

At last the supreme court decided the case in favor of Green on the ground that the plaintiffs had permitted him to spend so much money before having him enjoined. This fact created an estoppel. But for Senator Hanna’s political activity, he being a candidate to succeed himself in the fall of 1903 when this was going on, and the unquestioned fact that an injunction would hurt him he certainly would have moved before election day and prevented an estoppel. The city’s real success at last in creating a line from which extensions could be made was due to the fact that Senator Hanna sacrificed his street railroad interests to political necessity. He had been quoted as saying, “When I can’t combine business and politics, I will give up politics,” but public sentiment in Cleveland was making it increasingly hard to combine business and politics and even Senator Hanna had to defer to public opinion.

When at last those three miles of track on Denison avenue were completed they furnished the long desired base line from which other lines could be extended . It was the only bit of railroad in the city not under the control of the Concon, for by this time the merger of the Big Con and the Little Con had been effected. This merger was commonly attributed to my activity in the city’s interests. On July 6, 1903, the Concon commenced to sell six tickets for a quarter and to give universal transfers – clearly a measure of self-defense.

From this little line on Denison avenue extensions could be made and one after another was made. Property owners’ consent wars were raging on the streets all this time and the council chamber and the courts were the scenes of constant battles. The city was powerful in the council, the Concon powerful in the courts. First one side would move, then the other. As the franchises of the old company expired renewals instead of being granted to them were granted as extensions to the three-cent lien and so inch by inch the three-cent line grew longer and became more and more threatening daily. The administration policy already referred to of changing the names of streets was often necessary. This was the most intense period of the street railroad struggle so far, and for this reason detailed information as to dates and specific activities has been given. It was the fear that all grants as they expired would go to the three-cent-fare company which finally gave the city its most striking victory in the year 1907. That year the valuation of the street railroads of the city was made by F. H. Goff and myself after four months of public hearings, at the end of which time the property was leased to a holding company to be operated for the public good. I shall tell more of this later.

Simultaneously with the street railway war other matters of moment claimed my attention as mayor. I had become convinced that a combination existed among local contractors for running up the price of paving. It had been the custom to call for a few bids at one time. I decided to break up the combine by calling for bids on the entire paving for the year 1903. I called before me a representative of the Barber Asphalt company and told him that his company could never hope to do any asphalt paving for our administration since we did not believe in that kind of paving but that they might secure the brick paving for the city if he could assure me that they would could do it at a great saving to the municipality. When the bidding took place this company underbid the local contractors by one hundred and ten thousand dollars. The defeated contractors immediately got a restraining order from the supreme court enjoining us from entering into a contract on account of the illegal character of the charter under which the city was operating. Upon final hearing the injunction was dissolved. Luck was on our side in this case. Senator Hanna was not interested in street paving and he had no objection to supreme court decisions which did not affect him.

The editorial comment of one of the local newspapers was significant: ” The municipal administration was treated to a genuine surprise in the action of the supreme court dissolving the injunction in the paving contract. So accustomed has the administration become to supreme court injunctions every time it attempts to do anything that the action . . . was quite unexpected.”

Believing in the municipal ownership of all public service utilities, I was eager to take advantage of everything the laws made possible in this direction. For many years Cleveland had owned its waterworks, and though the municipal ownership of street railways was not nor is yet permitted, there was no legal obstacle to a municipal lighting plant and our administration took steps to establish one. On the night of May 4, 1903, when the new city government went into effect, an ordinance was introduced into council providing for a bond issue of two hundred thousand dollars. This passed by unanimous vote May 11. When the ordinance was published it was discovered that it was so worded as to provide for an “electric light and power plant.” It developed that there was nothing in the statutes to cover a power plant. In order that prospective buyers of bonds might raise no question on this point it was thought best to pass the ordinance again with the words “and power” eliminated. At once the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company got very busy. It didn’t want to be obliged to compete in the lighting business with its own best customer – the city. It went to council. That body was composed of nine Republicans and twenty-three Democrats: twenty-two votes were required for the necessary majority of two-thirds on all legislation of this character. The Illuminating Company succeeded in winning over three Democratic members. These men voting with the nine Republicans defeated the ordinance when it was again introduced. Another instance of what outside influence does to councils!

We decided then to call a special election on the bond issue and named September 8 as the date. On September 1 Attorney-General Sheets, at the instance of Thomas Hogsett, acting in the interests of the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company, brought suit to prevent the special election, and a restraining order was granted on the ground that the Cleveland board of elections was an unconstitutional body and that the Longworth act providing for special bond issue elections was likewise unconstitutional. The hearing was set for September 22, nearly two weeks after the date fixed for the election. It happened that on that very same day the city was also enjoined from entering into a contract with the Municipal Signal Company of Chicago for the installation of a police signal system.

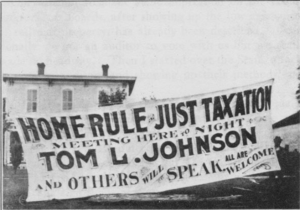

Our campaign for the bond issue election had been planned and the first meeting was scheduled for that night, September 1, so a few hours after the restraining order had been served, Mr. Baker, Mr. Cooley, Mr. Springborn and I presented ourselves at the tent and found our audience waiting for us. In its news report of that meeting the Plain Dealer said, “The old siren song of the injunction has not lost its charm. It was the injunction that neighbor talked of to neighbor, it was the injunction they came to hear discussed, it was the injunction that caused men to wonder that Mayor Johnson had the temerity to open the campaign at all.” Naming the speakers the report continued, “All explained the municipal lighting plant proposition with as great seriousness as if the matter were really to be disposed of next week.”

We had another meeting the next night and another the next, and the board of elections was providing for registrations to be on the safe side. In the meantime City Solicitor Baker hastened to Columbus and managed to have the hearing set for Saturday, September 5, three days before the proposed election. The hearing was held, Mr. Baker arguing for the dissolving of the injunction, Mr. Hogsett who by the way had been director of law under the administration preceding mine, and Senator Hanna’s every faithful Sheets, presenting the arguments against it. The supreme court refused to dissolve the injunction, our special election couldn’t be held and our municipal lighting proposition was retired to temporary oblivion.

How many times in our tent meetings, both in Cleveland and out in the State, when I was asked, “Why do you believe in municipal ownership?” such instances as this one came to mind when I answered:

“I believe in municipal ownership of all public service monopolies for the same reason that I believe in the municipal ownership of waterworks, of parks, of schools. I believe in the municipal ownership of these monopolies because if you do not own them they will in time own you. They will rule your politics, corrupt your institutions and finally destroy your liberties.”