Part I: History and Culture

Cultural Traits, National Life and Contributions

Dragoslav Georgevich

Serbian Culture

Serbian culture is based on Eastern Orthodox dogmas and ethics. Saint Sava expressed Serbian orthodoxy through the independent Serbian church which he established in 1219. This spiritual legacy has been lived by the Serbian people through their leaders, saints, literature, art, architecture, and institutions as well as by their thought, philosophy and whole way of life. Although Serbian culture is a part of Eastern Orthodox Christian culture, it is also a specific and unique culture of its own.

Serbian conversion to Christianity occurred in the ninth century but transformation to a Christian culture was slow and long. Only in the second half of the 12th century when the Great Zupan Stefan Nemanja centralized all political power into his hands did the situation become clearer. Nemanja expatriated the Bogumils, remained on good terms with the Roman Catholic church, but firmly embraced Orthodoxy and Byzantine culture.

From the very beginning of its existence, the culture of the Serbian Church was more spiritual than material. Its ethical influence on individual men as well as on the whole nation was strong and faithful. It determined the destiny of both the individual and the nation. The Serbian Church accepted both knowledge and faith and was able to influence the intellect and sensibility.

Spiritual Values and Mores

In order to understand the spiritual culture of the Serbian nation it is necessary to consider Serbian spiritual qualities. The basic characteristic of Serbs is their great vitality which is expressed through a strong instinct for self-preservation. However, this vitality is not an aggressive but a passive quality. Serbs possess the passive forces of defense and endurance rather than the active forces of movement and aggression.

Their historical development forced Serbs to become a nation of warriors, but not a nation of aggressors. Since they were subjected to many attacks, they became deeply distrustful. They learned not to expect good deeds or help from anyone, only unprovoked attack. Many times in their turbulent history the Serbs were sentenced to death. In 1813 after the First Serbian Revolt the Turks intended to destroy Sumadija completely. Hitler decided to do the same in 1941, but the Serbs survived both threats and outlived their aggressors. Out of resistance and endurance, heroism was born as an answer to aggression. Therefore, the basic spiritual quality of Serbs is to bear evil heroically, enduring all calamity until victory.

Serbs are excellent soldiers because heroism and warfare have been practiced throughout centuries. A high regard for heroism, struggle and endurance along with a love for military affairs are deeply-rooted Serbian qualities. Western writers noticed and described these Serbian qualities long ago. Throughout centuries Serbs fought against stronger enemies in defense of their homelands. An ardent love for liberty combined with a defensive nature, introduced perseverance, bitterness and sacrifice into the Serbian struggle for freedom.

The foremost Serbian spiritual values and mores are tied to war and struggle. They are heroism, self-sacrifice, word of honor, comradeship, patriotism, modesty, individualism and the ability to extricate themselves from difficult combat situations. Other qualities held in high esteem are a good education, brightness, good physical and mental health, beauty, wit, intelligence and modesty. Highly esteemed women are widows whose husbands lost their lives in war, mothers whose sons were killed in defense of their country and mothers of many sons, particularly those whose sons were courageous fighters in combat. Also admired are men and women who pledge their properties to schools, churches or benevolent societies, men who are able to find water and build fountains in dry regions, builders of churches and monasteries, and good story-tellers who relate national traditions.

Engineers, physicians, lawyers, authors, singers, musicians, famous sportsmen, and men or women able to treat bone fractures, snakebites, and small injuries inflicted by accident are admired. People with well-organized and well-kept households and those who produce good fruit are respected. This includes women who are excellent housewives and cooks and those who take good care of children and older people. Modern professional women, as doctors, professors or artists, also command respect. Because church and state are separated the church has less influence today, but clergy-men are still much respected as individuals and their advice is sought.

It is interesting to note that salt and bread have a spiritual value. They symbolize a desire for peace and are so respected that they are seldom thrown away. Salt and bread are brought before an enemy to eat and thereby show an acceptance of a peace offer. Oil and wine also have a spiritual value.

Spiritual standards are set very high for Serbian people, so it is difficult to receive recognition from neighbors, friends, relatives or the general public. A family’s reputation is much guarded. In Crna Gora people still live in clans and so public opinion is very sharply watched in regard to every individual. It praises good deeds and generally admitted values and virtues. It also registers, judges, scolds and rejects all worthless and weak behavior or deeds.

Cowards, dishonorable, immodest, or lazy people are despised. Stupid persons and fools are subjected to ridicule. Bad housewives are held in low esteem, selfish people are hated, egocentric people are disliked, and indecisive persons are so despised that about them people say, “They neither stink nor smell.” In particularly low esteem are those superiors who do not have enough courage to command. Opportunists are despised, particularly those who are always in agreement with the regime. Evil women, those with sharp tongues, are disliked, and avoided. Children and youth are admired and liked if they are gay, open, friendly and polite toward older folks. In schools the able, strict and just teachers are held in high esteem, while weak, soft or unjust teachers are despised. Politicians and leaders who do not fulfill their promises and who protect or favor friends and relatives are hated. In general, all weak, insipid and morally feeble behavior is despised by Serbs.

Material Values

Material value is attached to various expensive things or animals which are seldom purchased, highly treasured, and given away only in cases of emergency. They include jewels, such as rings, bracelets, necklaces, brooches, watches and gold coins (ducats and napoleons); old weapons, such as decorated knives, pistols, rifles and swords; various pieces of fancy, decorative, cloths, such as embroidered scarves, folk costumes, furs and fancy footwear.

Such valuable things are usually kept in a family for generations and given as an inheritance to children, relatives or friends. In many cases such heirlooms are transferred from one generation to another for hundreds of years. Gold coins are highly valued because of frequent wars, change in regimes and an unstable paper currency. Gold coins are not in circulation for money but only as decoration. Women make bracelets and necklaces out of them. Old arms are also used for decoration and they are usually hung on the walls of homes, particularly if they were taken from an enemy in war.

In Serbian villages high value is put on domestic animals and things used for agriculture, such as good horses, oxen, cows, mules, donkeys, roosters and shepherd or hunting dogs. Agricultural machines or vehicles and equipment for hunting and horses are important. People consider their vegetable and flower gardens, vineyards, bees, and wine barrels as valuable. Modern goods are highly valued today, such things as automobiles, bicycles, small appliances, musical instruments and fancy furniture. Sporting equipment is important since all sports are popular.

National Customs

Traditional courtesy is expressed in several ways. For many centuries Serbs lived a tribal and patriarchal life. In such a closed society unwritten rules precisely regulate the behavior and courtesy of all its members. One basic rule is that younger people must show respect to older members of the society. This respect is expressed by outward signs and, even more, by proper care and support. Older people must be greeted and, while speaking to them, younger persons stand. Seats on trains and buses are given over to them and, generally speaking, they are honored in every respect.

Material care for parents who are unable to earn their livings is the responsibility of their sons and daughters. Old parents may live alone or in the same household with their children. In villages they usually live on their own small properties, and if they are unable to take care of them, their kinsfolk do it. Sometimes one grandchild lives with them because grandparents are usually close to their grandchildren. Most Serbian children grow up under the care and guidance of their grandparents.

Greetings are also determined by centuries-old customs. Younger people should greet older ones first. Those who enter a home first extend greetings to those they find within. In addition to a spoken greeting, male persons greet others by taking their hats off. Relatives address each other by their terms of relationship, such as uncle, aunt, grandfather, grandmother, and so on.

Hospitality is a very old Slavic custom. In early times hospitality was intended to take care of travelers who may have gone astray in a strange country and needed shelter, food and protection overnight. This custom continued to exist after Slavic conversion to Christianity because during the Middle Ages the number of travelers was substantial.” Emperor Dusan’s code contained very heavy punishment for any village in which a traveler should suffer certain mishaps. That custom was kept when Serbs were under Turkish rule. Travelers also acted as messengers by transferring news from one region to another. Travel was difficult at that time so travelers enjoyed respect and attention. Many of them were gusle players who knew many folksongs. They also played patriotic and heroic songs which contributed to Serbian national feeling. Hospitality was particularly given to those travelers who collected donations for repair and maintenance of churches and monasteries. Travelers of the kind described above are very few today, but the hospitality remains.

Engagement between two persons wishing to marry was done in olden days with the consent of the parents of the girl and boy. In modern times it is an affair between the two people who plan to marry. After the couple decides to be engaged, they inform their parents, relatives and friends and a party is usually given for invited guests. The Serbian Orthodox Church participates in this custom by making an announcement three times in the church. In these announcements the parish priest says the names of the engaged couple and invites all people to make any appropriate objections.

A wedding ceremony may be performed by a clerk in a special office or by a priest in a church or home. After the wedding a party is given for invited guests at home, in a restaurant or in some other suitable place. The bride and groom are dressed in their best clothes. In Serbian villages weddings are big social events. Very often a long procession composed of many vehicles follows the bride and groom to the church and back to the place where a banquet is given. The whole affair is joyous; much food and drink are consumed. Music is played and guests sing and dance for hours.

Kumstvo, or sponsorship, is a custom which exists in the Balkans among all Christians. Both Orthodox and Catholic Serbs still practice this custom, but nowadays less than in the past. A kum, or kuma if female, is one of the two witnesses who officiate at the wedding of a couple. In the Serbian Orthodox Church the kum puts wedding rings on the ring fingers of both bride and groom and also signs the marriage contract. With this act a kum becomes a relative not only of the couple but also of their families. In addition to his participation in the wedding, a kum becomes godfather to the children of the couple. He holds the infant during baptism and gives it a name, usually with the consent of the parents. If a godfather can not attend the baptism, he appoints a substitute to officiate in his place. Serbian custom requires that kumstvo be kept throughout many generations.

The Slava is a Serbian Orthodox religious custom which dates from the time of conversion to Christianity. Each family celebrates the saint’s day on which their ancestors became Christians. The House Patron Saint who protects the family is inherited by all male members of the family from their fathers. A woman celebrates her father’s Slava if unmarried and her husband’s if she is married. A Slava is always celebrated at home. On that day a special bread (slavski kolac) and specially prepared wheat are consecrated by a priest either at home or in church. Bread symbolizes the body of the saint and the wheat is for his soul. For a few immortal saints like Archangel Michael and Saint Ilya, wheat is not prepared, only the bread.

On Slava day the house is open for all visitors, both invited and uninvited. Each guest is treated to food, drink, coffee and cakes. Special guests and relatives are invited for dinner. A Slava is both solemn and joyous. Serbs have kept this custom through centuries, even under the most difficult conditions. The most frequently celebrated Slavas are Saint Nikola, Saint Jovan, Saint Dimitrije, Saint George and Saint Sava.

Serbian outings are much like American picnics, but many of them have religious origins. Saint George’s Day (Djurdjevdan) on May 6 is an old Serbian holiday dedicated to the memory of hajduks, guerrilla fighters against the Turks. In the past it was the day when all fighters gathered at certain places, organized small units and began their campaigns against the Turks. They fought the enemy up to Saint Dimitrius‘ Day at the end of November when they disbanded and went to their villages to await spring and Saint George’s day when trees were bearing new foliage. At present Yugoslav Communists do not celebrate Saint George’s Day, but they have their labor day on May 1. People in villages and small towns do keep Saint George’s Day by going early in the morning into fields for picnics. Serbs in the free world celebrate this day regularly with singing, music, dancing and sports events.

Another religious celebration is known as Zavetina. This takes place once a year at a certain place called “zapis,” usually an oak tree. After a religious ceremony with a parish priest officiating, all participants have a picnic. Each church has its patron saint and once a year on the saint’s day (Slava) people celebrate with a service and picnic in the church courtyard. Christ’s resurrection is celebrated in Crna Gora where people believe that before Easter no one should go into the mountains. All the villagers gather at certain places, celebrate Easter and after that shepherds depart to the mountains with their animals. Bairam is a moslem religious festival which occurs after a long period of fasting. It is a great outing, usually close to some creek or river. Such a place is called “teferic” and the outing is also called by this name.

Friends and relatives get together for the departure of recruits to military service. This outing is held once or twice a year in villages or towns when new conscripts gather in order to go together to barracks for basic training.

In Macedonia they celebrate the departure of workers for other parts of the country to work and save money. This happens because most young men must be able to prepare dowries for wives. In other Serbian lands the dowry goes to the groom, but in Macedonia it is given to the bride’s parents.

An old Serbian custom called Moba helps families at harvest time. Friends come to work free of charge and after sunset the host family serves a meal around a fire.

Saint Sava’s Day is an important religious and national holiday for Serbs of the Serbian Orthodox faith. It is celebrated on January 27, the day Saint Sava died in 1235. Serbian churches in Yugoslavia and churches and schools in the free world celebrate Saint Sava‘ s Day to commemorate this great Serbian reformer and teacher. On this day selected contestants receive awards for special papers prepared for the celebration. Before the Communist party took power in Yugoslavia all Serbian schools including universities celebrated Saint Sava’s Day.

Vidovdan (St. Vitus Day), celebrated on June 28 (June 15 by the Julian calendar), commemorates the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 when the Serbs were defeated by the Turks and the flower of Serbian nobility lost their lives. Vidovdan is also like the American Memorial Day devoted to the memory of all soldiers who fell for the nation and the country through the centuries from Kosovo to the present. On that day all Serbian churches have a requiem with an appropriate patriotic speech by the priest or a prominent man of the community.

Christmas Eve is celebrated by Orthodox Serbs on January 6 which is December 24 on the old Julian calendar. Serbs of Orthodox and Roman Catholic faiths hold similar celebrations with some small differences. Every Orthodox home has a small oak tree from the forest called “Badnjak.” In the evening the landlord takes the tree into the house. When he enters he greets the members of the household with, “Good evening, happy Christmas Eve to you,” (Dobro, vece, srecno vam Badnje vece). One man from the household sprinkles him with mixed cereals, corn, wheat, rye and oats, and answers, “God give you good, lucky and honorable man,” (Bog ti dao dobro, srecni i cestiti). Then the landlord puts the tree on the fire to burn.

Catholics and also many Orthodox Serbs have in their homes Christmas trees decorated as they are in America. There are also packages with presents for all members of the household. This custom among Serbian Orthodox people started after World War I but only in the cities. Villagers did not accept it, not even at the present time, and have only Badnjak. In Dalmatia both the Orthodox and Catholics have Christmas trees and Badnjak. A decorated tree is a custom children like very much and so it is spreading among the Orthodox Serbs.

A Christmas Eve dinner consists of dishes used for fasting, such as beans, fish, noodles, honey, prunes, apples and walnuts. In many homes straw is spread on the floor to symbolize the hut in which Jesus Christ was born. The first person to enter the house on Christmas Day is called Polazenik. His duty is to stir up the fire with a firebrand of Badnjak and extend good wishes to the family. He usually says, “As many sparks, so much money, health and progress to this home.” A Polazenik should be a child because children are believed to be less sinful than adults and good blessings will follow the family all year. A Polazenik is invited for dinner.

The Serbian Orthodox Christmas is celebrated for three days, while the Roman Catholic one is celebrated two days. In a Serbian Orthodox home no one leaves the house on the first day except to attend church. Dinner on that first day is a special affair with a huge meal. A roasted suckling pig is the main dish with various other side dishes. A wheat bread called “cesnica” with a hidden coin inside is divided among members of the household and guests. One piece is saved for “the traveler,” thus symbolizing Christian charity. Serbs of Roman Catholic faith do not have the Polazenik and cesnica, but their celebration of Christmas is more or less the same as for the Orthodox. To offset the religious Christmas celebration, Communists have an official New Year as their state holiday. Christmas is a work day and absence from work is not permitted.

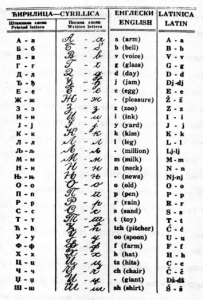

Serbian language

Before their arrival in the Balkans the Serbs, like all other Slavs, spoke the Proto-Slavic. language. During their movement from Boika to the south, Serbs gradually developed their own language, probably from a dialect of the Proto-Slavic language. This development of the Serbian language and creation of a literary language was greatly influenced by the work of two Slavic Apostles, the brothers Cyril and Methodius. They were Greeks from Thessalonike, who learned a Slavic language in order to convert Slavs to Christianity and translated church books from Greek to Slavic languages. In the beginning there were two scripts, Cyrillic and Glagolitic. Cyrillic has survived with certain modifications up to the present day, while Glagolitic has disappeared. The language used in literature for a long time was Church-Slavic. Only a few people among the Serbs were educated from the 9th through the 11th centuries. Clergymen were educated and used Church-Slavic in their writing. The Serbs of Roman Catholic faith used the latin script and often the latin language.

The arrival of the Turks in the Balkans and the downfall of the Serbian state interrupted literary work by educated Serbs. The only places where a few men could work on literature were monasteries. While writers wrote in a mixture of Russian and Serbian Church-Slavic languages, the people continued to use their folk language which was different. Many authors were educated in Russia and were influenced by the Russian language. The first educated Serb who opposed the use of a mixed language was Dositej Obradovic. He was the first president of the Great School at the time of Karadjordje, the school which was the first Serbian university. His book Zivot i prikljutenija Dositeja Obradovica was written in the Serbian people’s language.

The great Serbian philologist Vuk Stefanovic-Karadzic worked lang and diligently on the reform of the Serbian language, beginning in 1814 when he published the first Serbian grammar and a collection of Serbian folk poetry in Vienna. Vuk fought a long and persistent battle until the people’s language was recognized as the Serbian literary language. His intention was to establish a Serbian literary language by rejecting the Kajkavski dialect in favor of Stokavski. This second dialect had three subdialects, jekavski, ekavski and ikavski, and Vuk wanted jekavski for the literary language. However the Serbian educational center in Novi Sad, which was under Austria-Hungary, and the government of Serbia in Belgrade accepted the ekavski subdialect in schools, administration and printing. He had to yield to the subdialect which was perpetuated by official use. Vuk’s battle was crowned by victory because his reforms were accepted and the spoken language of the common people became the written Serbian language. The jekavski subdialect survived and today it is equal to the ekavski, while the ikavski subdialect is disappearing.

Scientific Contributions

The first scientist of Serbian origin was Rudjer Boskovic who was born in Dubrovnik in 1711 and died in Milan, Italy, in 1787. His family was from Hercegovina originally and his two brothers were talented mathematicians. Rudjer’s father was a merchant and he lived for a time in the Serbian town Novi Pazar in Raska. He acquired his elementary education in Dubrovnik, entered the order of Jesuits and after graduating became a teacher of mathematics in the Collegio Romano. Through all his life Rudjer worked in science. His contribution to astronomy was a geometrical method to determine the position of the equator and planets. He also worked on a molecular theory of matter, measured the size of a meridian angle, accepted and defended Newton’s ideas and originated an atomic theory. In 1773 the King of France appointed him to work on nautical optics for his navy. In 1783 Budjer retired to Italy to supervise the printing of his voluminous scientific works which were written mostly in Latin but also in French and English.

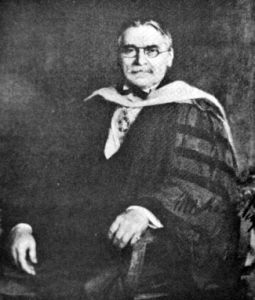

Mihailo Pupin Idvorski was born in Idvor, Banat, Vojvodina, in 1858 and died in 1935. He arrived in America in 1874 and graduated from Columbia University in 1883. As holder of the John Tyndall Fellowship of Columbia he studied at Cambridge University in England and under von Helmholtz at the University of Berlin where he received his doctorate. A professor of electromechanics at Columbia from 1901 to 1931, he was the inventor of long distance telephony by means of self-inducting coils. His system was acquired by the Bell Telephone Company and by German firms. His other inventions were in electrical wave propagation, electrical resonance, iron magnetization and multiplex telegraphy. He published Electro-Magnetic Theory (1895), From Immigrant to Inventor (1923), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize in 1924, The New Reformation (1927), and Romance of the Machine (1930). Professor Pupin was appointed honorary consul general in New York by the King of Serbia. He was an active supporter of Serbia during World War I and at the Paris peace conference in 1919 he helped the Serbian delegation acquire favorable borders for Yugoslavia.

For his scientific achievements and contributions in other fields Pupin was awarded many medals and honors such as the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, the John Fritz Gold Medal and the Elliot Cresson Medal of Franklin Institute. President Harding paid a compliment to Pupin in a letter to him dated October 14, 1922: “I take this occasion to record recognition and appreciation of the fact that by virtue of experiments conducted and directed in your laboratory, you were successful in contributing in an important respect to the development of one of the marvels of our age, the radio telephone.”

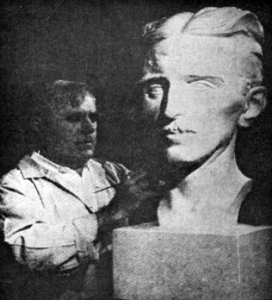

Nikola Tesla was born in Smiljan, Lika, in 1856 and died in New York City in 1943. His father Milutin was a Serbian Orthodox priest who worked hard for the development of Serbian national consciousness, education and economic development in various places in Lika which at that time was under Austria-Hungary. Nikola’s mother Georgina was also an inventor as was her father. After graduating from secondary schools in Gospic and Karlovac, Nikola studied at the Polytechnic School in Gratz and at the University of Prague. He developed his first invention in Budapest in 1881, a telephone repeater. He arrived in the United States in 1884, became a naturalized citizen and worked for a time with Thomas Edison. His original works include a large number of electro-technical inventions in the field of poly-phase systems. He invented a system of arc lighting (1886), the Tesla motor and alternating current power transmission system (1888), a system for electrical conversion and distribution by oscillatory discharges (1889), high frequency current generators (1890), the Tesla coil (1891), a system of wireless transmission of information (1893), mechanical oscillators and generators of electrical oscillations (1894-95), and a high potential magnifying transmitter (1897). The inventions for which he has been known as an epoch-making inventor were alternating current motors and the famous Tesla coil or transformer. He was one of the outstanding geniuses in his field and his contribution to humanity was enormous.

Jovan Cvijit (1865-1924) was a professor of geography at the University of Belgrade, founder of the Geographical Society and president of the Royal Serbian Academy of Science. He was an expert in the field of geomorphology. His published works are Geomorphology, Anthropogeographical Problems of the Balkan Peninsula, The Karst and Man, and Geography and Geology of Macedonia and Old Serbia. Professor Cvijic was an internationally known contributor to geographical science.