Part II: Immigration and Settlement

Serbian Immigration to the United States

Dragoslav Georgevich

Reasons for the Immigration

Before 1920, immigration to the United States was unrestricted. That period may be divided into two different phases. During the first phase from 1820 to 1896, according to the government records, most immigrants came from countries of western and northern Europe, that is, from the British Isles, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland. During the second phase from 1890 to 1924 the majority of immigrants came from countries of central, eastern and southern Europe, mainly from Austria-Hungary, Russia and Italy. After the adoption of the immigration law which restricted immigration by establishing quotas, the tide was turned. Countries of northern and western Europe gave more immigrants to the United States than the central, east and south European countries.

South Slavic immigration followed the European pattern. Until 1890 only a trickle came to America, but since then the tide has swelled and the movement increased. The immigration of Serbs to the United States was never so strong as that of other nations. During the 1880’s Croats, Slovenes and Serbs from Austria-Hungary immigrated in masses to the States. A majority of Serbian immigrants were from provinces which were under the rule of Austria-Hungary: Croatia, Slavonia, Dalmatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina. A large number of them were people whose ancestors were for centuries peasant-soldiers in the Military Frontier of the Austrian empire. Their situation after the abolition of the Military Frontier in 1873 became so unfavorable that they decided to immigrate to the United States. They were from the Vojvodina, Slavonia, Lika and Krbava regions. Serbian emigrants from the two independent Serbian states, the kingdoms of Serbia and Crna Gora (Montenegro) were few in number. The same is true for the Serbs from Macedonia who were under Turkish rule. After the creation of Yugoslavia in 1918 the number of Serbs who immigrated to the United States was small. Around the beginning of World War II the number of immigrants began to increase and reached a peak in 1952.

The causes for Serbian immigration to the United States were mainly the same as for other people of Europe: bad economic conditions in their homeland and detrimental political factors in Austria-Hungary. The Kingdom of Serbia made significant progress in her economic, social and political life, particularly after 1880. Ownership of land was in peasant hands, industry although only in an initial phase was making a good beginning, and the political situation under King Petar I Karageorgevic was greatly improved. The king introduced a completely democratic system similar to those in Western Europe. Therefore Serbs did not immigrate to other countries from Serbia.

Serbs in Austria-Hungary, like all other Slavs, lived under strong political and economic pressures. The best land was held by rich landlords, mostly Austrian, Hungarian or Croatian nobility. Rural areas under the dual monarchy were overpopulated and impoverished, and people struggled with each other and the nationals of German origin who behaved as a privileged class. Serbian peasants in Austria-Hungary were living on small plots of land and could not compete either with the great landlords or with the German and Hungarian farmers who were favored by the Austrian government. Wages were low, taxes were high, industrial development was slow and cities were unable to absorb agricultural workers who were forced to leave the land. It is no wonder that poor Serbian peasants decided to escape to America to improve their ways of life.

Another phenomenon that contributed to immigration to America was the break-up of the Zadruga or family cooperatives. This occurrence deprived peasants of their livelihood because it caused an excessive subdivision of land. In Dalmatia, for example, the average size of peasant holding was 1.5 acres and yet 86% of the population was supported by agriculture and forestry. Arable land was scarce in Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosnia, Hercegovina and Crna Gora (Montenegro) particularly in the karst areas which have very little land for agriculture.

Compared with the economic situation in Serbia and Montenegro, Serbs in Austria-Hungary, although politically and economically oppressed, had better life conditions than their compatriots in those free lands. With the exception of peasants from the karst, Serbian farmers in Vojvodina and Slavonia had more and better land and better markets for their produce than Serbian farmers in Serbia or Montenegro. Yet in spite of this situation, peasants from both both provinces emigrated in large numbers. Clearly the Serbs in Serbia and Montenegro stayed at home because they had their national states and freedom.

On the Adriatic coast a very serious agricultural problem was caused by phylloxera, a plant lice. Most of the Dalmatian vineyards were destroyed in the 1880’s. Although total catastrophe was avoided by use of special vines which resisted phylloxera, the damage inflicted to vineyards substantially increased emigration. Other economic activities on the coast weakened the economic fortunes of Dalmatian fishermen. Outmoded fishing equipment, obsolete ships and a diminishing of the fish population caused a constant decline of the fishing industry. Dalmatian fishermen were unable to buy better equipment for fishing and to compete with modern steam-powered ships. Thus farmers, sailors and fishermen looked at emigration as an exit from their unfavorable economic situation.

Serbs in Austria-Hungary had other good reasons for emigration, one of them being compulsory military service which lasted for three years. The pay in the dual monarchy military service was very low for an army private or for an ordinary seaman: three to five dollars a month. Discipline was strict and the life of a serviceman was hard because the monarchy had frequent diplomatic crises and wars. The draftees were forbidden to marry and they served far from home. Austrian officers and noncoms treated Slavic enlisted men harshly, often with ridicule.

Letters from friends and relatives who had immigrated to America described favorable conditions and encouraged further immigration. Returning immigrant-visitors were better dressed, had more money to spend and brought valuable gifts from America. Although they tended to exaggerate their achievements, they nonetheless influenced many young men to leave for the land of unlimited opportunity. This was particularly true for those who had read adventure stories about American Indians, explorers and pioneers. Often relatives in America paid the passage for young immigrants. The few migrants who were unsuccessful or lost their health in the new land and returned home did not deter this movement.

Social reasons also caused immigration. In Austria-Hungary as well as in Serbia and Crna Gora, society was already stratified. Two principal classes existed there, the city people and rich land-owners called gentlefolk (gospoda) and the common people (narod) and peasants (Seljaci). The upper class very often exhibited superiority and arrogance toward the lower class. Bitter strife and resentment existed between them. Another motive for immigration was occasional bad family relationships, scandal and friction with the desire to escape to a new life elsewhere.

Steamship companies and mine owners sent agents abroad to influence and encourage immigration of new laborers. Although the recruiting of foreign labor was made illegal by federal law in 1885, various agents violated this law both directly and indirectly. The first immigrants to America were from Dalmatia. Many Dalmatians knew more than one foreign language and were able to find good jobs in America. Others from Austria-Hungary, Crna Gora, Serbia and lands under Turkish rule were able to get only difficult or dangerous work such as in construction, steel plants, mining and manufacturing. Continental immigrants went to mines in northern Minnesota and copper mines in northern Michigan. They were also concentrated in the industrial cities of New York, Milwaukee, Cleveland and Chicago and the mining centers of Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

Method of Transportation and Costs

Travel from their homeland to America was usually by railroad train from Serbia, Vojvodina, Bosnia, Hercegovina or Croatia to a seaport on the Adriatic coast. The large ports at that time were Trieste and Rijeka from which large transatlantic ships sailed to America. However, many emigrants went to the large West European harbors of Genoa, Marseilles, Le Havre, Bremen or Hamburg.

Individual Serbs immigrated to America throughout the whole 19th century and into the first decade of the 20th century. In 1892 a group of several hundred Serbs from Dalmatia and Montenegro settled in California. Sailors from Dalmatia came to Louisiana and California, many by simply abandoning ship on arrival in an American port. Some of them disembarked in New York and traveled overland to California. Others settled in New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Ohio or Illinois. Only a few settled in the South. All of them traveled by rail. The cost of transportation between Austria-Hungary and the United States in the first decade of the 20th century was from 60 to 80 dollars. This was a very large sum of money for an immigrant. To pay for a trip to America the family of an immigrant had to sell half of their animal stock. On the other hand, if an immigrant wanted to finance travel for a relative he needed four to six months of very hard labor in a mine or factory to save the 60 to 80 dollars for one fare. At that time hourly wages were so low that only about one dollar could be earned in a ten-hour work day.

Serbian immigrants to the United States were mostly young men without wives or children. They came with some relatives or friends revisiting their old homes. Their ages were 14 to 44 with an average of 20 years. The Serbs who immigrated to the United States by 1910 were of working age, so their movement is characterized as a labor migration. They were of two kinds. One group wanted to work for a time and then return to their homes with savings. The other group expected to stay permanently and bring their families from the home country after saving enough money to pay for the trip. They wanted first to improve their economic situation and then to bring their families or get married.

Government Policies Concerning Immigration

In 1924 the immigration conditions for all South Slav and East European immigrants worsened. The immigration law of 1924 implemented a policy of restriction and reduced the number of immigrants by quotas. From 1921 to 1950 a total of 5,670,679 immigrants arrived in the United States. Of this number 21% were from Canada and Newfoundland, 14% from Mexico, the West Indies and Central and South America, 34% from northern and western Europe, and 26% from southern and eastern Europe. Less than one percent (56,475) of the total number was furnished by Yugoslavia. The number of Serbs among them is not known, but certainly it was very small. During the depression years of 1931-1939 the number of Serbian immigrants to the United States together with Bulgarians was only 2277, while at the same time 3749 emigrated from the United States.

During World War II and after it, the number of immigrants was increased to hit a peak in 1952, but a large majority of them were nonquota immigrants. The Yugoslav annual quota by the 1924 immigration act was 611, raised to 845 in 1929. This quota was sometimes unfilled. The nonquota immigrants were mostly displaced persons and refugees. These immigrants who entered the United States during and after World War II were a different kind of people. They were not illiterate or unskilled laborers but mostly intelligent, educated, well-trained semiprofessional and professional people. Among them were clerical workers, craftsmen, farmers, managers, teachers, merchants, doctors and scientists. The 1948 Displaced Persons Act favored immigration to the United States of all members of allied armed forces who fought the enemy of the United States during World War II. The number of Serbs who used this privilege for immigration was 17,238. They were mainly former Serbian prisoners of war in Germany and Italy who chose not to return to Yugoslavia because of political changes at the end of World War II. The Refugee Act of 1953 and the Acts of 1960 and 1965 brought thousands more of new Serbian immigrants. The total number of Yugoslav citizens who immigrated to the United States between 1946 and 1968 was 99,152 of which 16,000 were not Slavs but Volksdeutsches born in Yugoslavia.

Serbian Immigration to Other Countries

Serbian immigration to the United States is only one of many Serbian migrations in a 13-century-long history. In the 14th century the Turkish invasion and oppressive rule over Serbian lands caused several large scale migrations to the north and west. Throughout four centuries, first Hungary and then Austria gave Serbian immigrants special privileges in exchange for their services in the Military Frontier. After the Turkish danger diminished, the Roman Catholic Church tried to exercise a pressure against the Eastern Orthodox Serbs in order to convert them into Roman Catholics. Serbian reaction to this was another large scale immigration to Southern Russia. More than 100,000, perhaps even 200,000, Serbs from the Banat, Backa and the Moros districts immigrated to Russia between 1751 and 1753. Those Serbs in Russia have been assimilated, although as late as 1910 there were pure Serbian villages in the district of Jekatarinoslav. Besides those large Serbian immigrations to Hungary, Croatia, Russia and the United States, there were smaller immigrations to South America, Australia and various European countries. Several thousand Serbs immigrated to those lands between the 14th century and the present.

It is almost impossible to establish the number of Serbs in the United States. Statistics list Serbs by their country of birth, as Dalmatians, Montenegrins, Austrians, Bosnians, Hercegovinians and Serbians. Immigrants were often confused or ignorant about political changes in Europe and gave authorities erroneous information. A more reliable estimate of Serbs in the United States was obtained by a survey of various Serbian political, cultural, religious and social organizations. Counting the foreign born Serbs with the first, second and third generations, there may be about 200,000 of them.

The present Yugoslav government welcomes retired American pensioners because they bring in much needed foreign currency. The high buying power of the dollar in Yugoslavia makes this attractive to some, but changing government regulations create a life there that is unstable. Most Serbs in the United States are citizens who plan to make America their permanent home.

Serbian Contributions to America

Serbian contributions in the field of science by the two most important persons, Michael Pupin and Nikola Tesla, have already been described. It is necessary to repeat that they were world famous scientist-inventors whose inventions created in America benefited humanity as a whole. Pupin’s contribution was in long distance telephony and wireless telegraphy and Tesla was an electric wizard under whose name are listed about 700 inventions. Probably many more of his discoveries were not registered at all. Tesla not only invented new devices, but also he discovered new principles and new fields of knowledge. Just a few of his inventions are his motor, the essentials of radio and radar, neon and other gaseoui-tube lighting, fluorescent lighting, high-frequency currents and remote control by wireless. Nikola Tesla’s nephew, Nikola Trbojevic, works in the American automobile industry and has many patented inventions.

Serbs have made a substantial contribution to education. Dr. Paul R. Radosavljevic was a professor at New York University and Chairman of the Experimental Education Department. He wrote books in the Serbian, Russian, German and English languages. His published works are Experimental Psychology, Experimental Pedagogy, History of Experimental Psychology, and New Movements in Education. His monumental study is Who Are the Slavs? Among other teachers and authors of books in their special fields are Dr. Wayne S. Vucinic, Stanford University; Dr. Alexander Vucinic; Dr. Michael Petrovic; Dr. Alex Dragnic; Dr. Gojko Ruzicic; Dr. Milorad Draskovic of Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace; Dr. Milomir Stanisic, Purdue University; Dr. Milan Djordjevic, University of Alabama; Dr. Nicholas Moravcevic; Dr. Nikola Pribic, Florida State v University; Dr. Caslav Stanojevic, University of Missouri at Rolla; Dr. Milos Velimirovic, University of Wisconsin; Dr. Milan Vucic, Wisconsin State University; and Dr. Ilija Yoksimovic, Show University, Dr. Stephen Stepancev, King’s College, New York; Dr. Eli Orlovich, Iowa University.

Representing Serbs in the arts are the painters Borislav Bogdanovic, Tanasko Milovic, Vuk Vucinic, Milan Bulovic, Sava Rakochevich and Alex Dzigurski. A number of Serbs have achieved fame in the movie industry. Among them are Karl Malden (Mladen Seku1ovic), Bill Radovic, Marta Mitrovic, John Vivyan (Ivan Vukojan), Bob Obradovic, George Milan and a new promising film director Peter Bogdonovic.

One of the most celebrated sculptors is John David Brcin (fig. 6) who has received many awards in his field; his works have been shown throughout the country.

Many young Serbs have distinguished themselves in various sports, particularly in football. Bob Gain, Branko Kosanovic, Steve Rutic, Mike Nixon and Nick Skoric are a few prominent names in football. Also well known are Walter Judnic, Walt Dropo, Eli Grba and Emil Verban in baseball; Peter Maravic in basketball; Bill Vukovic in car racing; and Pete Radenkovic in soccer.

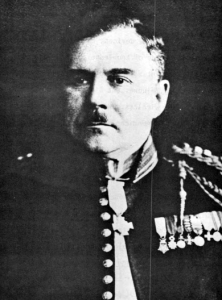

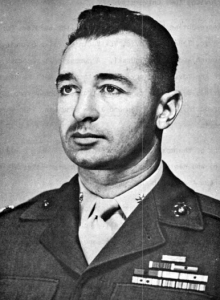

The only American who ever won two Congressional Medals of Honor in war was Captain Louis Cukela (fig. 7) of the United States Marines. Two other Medal of Honor winners were Alex Andjelko Mandusic and Mitchell Page (Milan Pejic) for heroism on Guadalcanal (fig. 8). Petar Tomie died at Pearl Harbor and was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. George Miric and George S. Wucinic both received the Distinguished Service Cross, and Steve Mandaric achieved the rank of Rear Admiral.

Serbs who contributed to the American economy are numerous so it is sufficient to name just a few of them. They are Mihailo Ducic, a dairy man; Stjepan Kralj and Todor Polic, builders; William Salatic, Gillette Safety Razor Company; William Jovanovich, president of Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich Publishing Company; Thomas Dabovich, Morton Chemical Company; and Daniel Maximovich, Skil Corporation. Serbs who were workers in American industry, mines, fishing and agriculture gave a great contribution to the United States economy.