Part III: The Serbian Community of Cleveland

Early Serbian Settlers

Nikolaj Maric

Problems of Adjustment

Cleveland’s first Serbian immigrant was Lazo Krivokapic who arrived in 1893. Although most early immigrants to the United States were laborers, Krivokapic was not. Well-educated and multi-lingual, he had served his country as a diplomat in Constantinople prior to coming to America. Here he owned a real estate business near East 25th Street and St. Clair Avenue where his linguistic skill proved most useful. Since there were no other Serbs in Cleveland, Krivokapic joined a Greek enclave because he spoke their language and shared their Eastern Orthodox religious beliefs. He felt at ease with them, too, for in Europe, Serbs and Greeks were traditionally good neighbors.

For years after their arrival in America, immigrants commonly suffered from homesickness and loneliness, taking solace from companionship with fellow countrymen. While living among the Greeks, Krivokapic continually searched for a fellow Serb. After nine years he encountered a factory worker named Grahovac as he strolled along St. Clair Avenue. Their friendship and the humble beginning of the Serbian Colony of Cleveland were recounted in a Plain Dealer feature on September 28, 1964.

Other Serbs arrived around 1910 and experienced problems similar to those of Krivokapic. Some of the problems stemmed from an old Serbian tradition of living in huge families, zadruge, as they were called. As many as 60 people lived under one roof and one command –the eldest male in the family. Grandfather made the major decisions, grandmother prepared the food and tended the small children, while other family members performed domestic and farm chores. Life was simple and, in many ways, carefree.

Even in the delicate matter of choosing a marriage partner, the elders in the household usually made the decision. The story is told of the way 23-year-old Aran Ve1isavljevic from Slavonia, Yugoslavia was married in the early 1900’s. He was the youngest of four brothers and it was his turn to get married; the family convened to select his bride. There were two candidates. Each girl came from a good family and had a sizeable dowry. Aran sat quietly as the older brothers argued whether to choose the one west of the village, or the one who lived east. Nobody asked Aran what he thought about either one of them. It was late at night, and the family was still arguing about the choice when the oldest brother came up with a solution. They would harness the horses in the morning, loosen the reins, and let the horses go to the east, or to the west as they chose. Thus was decided the future of young Aran Velisavljevic. Even the bride did not seem to mind the way she was “chosen” over the other young girl.

Serbs arriving here in the early 20th century found the change in life style traumatic. Young, unmarried men arrived alone, often intimidated by their environment and possessed of meager funds. For the first time in their lives, they had to make their own decisions and provide food and shelter for themselves. And compounding their problems was the need to learn English as quickly as possible.

To be Serbian is to be sociable. Socializing is intrinsic to the Serbian way of life. Households are geared toward hospitality, a hospitality which is closely linked to their religious beliefs. For Serbs, every event from birth to death over the centuries has been humanized and celebrated in a special way through their revered Eastern Orthodox religion. Cut off from this ritual which daily revitalized his life, the immigrant could not help but feel alienated by the stark and lonely life he was forced to lead in his adopted land. However poor he had been as a peasant in Europe, he was continually sustained by the warmth of family ties and a vibrant religion. In America he had no such solace. When he came here, he stayed, most likely, in a boardinghouse or, if he were so blessed, with a relative who had preceded him here. His life was a daily grind of long hours and hard work for meager wages in whatever nearby factory or shop needed his unskilled hands.

Many of the early immigrants, Serbs and others, hoped to work and save enough to return to their native lands and establish themselves well there. Some saved to bring other members of their family to America. Whatever their goals for the future, they came to realize that to survive and be happy in America, they would have to reestablish their social and religious traditions here.

Meanwhile, the comfort of lonely hours for the immigrant was the nostalgic memory of his homeland. He recalled such pleasures as wedding celebrations which went on for several days and nights as friends and relatives sang and danced and feasted. No expense was spared, though the newlyweds’ parents might have to live frugally for some time to pay for the reception.

Celebrating the Slava was another event that went on for days. Slava referred to the patron saint under whose protection the household was placed. The house was “open” to the village and hospitality extended to all.

Other ordinary activities which were elevated to occasions of merrymaking were harvesting, corn husking, wine making and picking feathers for the stuffing of pillows. This rather idyllic life was hardened somewhat, however, by the harsh reality that the small patch of land worked by the average farmer provided little hope for future prosperity; frequently it was hardly enough to sustain a sizeable family. Consequently, many young men sought to better themselves economically by immigrating to America.

The early Serbs in Cleveland retained whatever they could of favorite traditions. Whenever they could obtain the services of an Eastern Orthodox priest, they would worship simply in a store front- a considerable comedown from the exquisite churches and elaborate ritual they had known. The feast day of the beloved St. Sava continued to be a joyful event. In an article appearing December 1959 in the Serbian-American newspaper American Srbobran, author Stevo Ivancevic described the occasion as follows:

On Hamilton Avenue there were five berths (boarding places) where about 100 young, Licani (Serbs from Lika) were living. At seven in the morning, as if someone issued a command, the St. Sava’s songs were reverberating, and at the end of each stanza: My dear Bania, Lika and Krbava (provinces in Yugoslavia)! So help me, one would think he was in Atos listening to the monks sing. I was visiting the respectable family Banjanin with twenty other Serbs. After the songs were finally exhausted Mile Vukadinovic told us that he had heard some tamburitzans were to perform at the hall. This hall belonged to Janko Popovic called “Uncle,” on st. Clair Avenue. The building was relatively big, two stories – the hall upstairs, the saloon downstairs. At the time many buildings, including this one, had no electricity. Petroleum lamps were used for lighting, with glass cylinders and some sort of material used as wick, which, when burnt out, remained inside the lamp and gave better light. The only drawback was that these wicks could not withstand any tremors.

The St. Sava’s celebration that evening was better and richer than ever, because the organizing committee had brought the best tamburitzans from Detroit called Krisom Sremci. At seven in the evening the hall was already full of young, powerful males, mostly Licani. The rest consisted of our Vojvodjani and a number of young women. There were six tamburitzans, five small ones and one big one – bass. Licani were particularly impressed with the big one. “You could make a berth out of it,” commented one, while the others broke into laughter.

Gajo Germanovic, the host for the evening, was ceremoniously dressed in coattails, full cylinder on his head, cane in hand … “Look at Gajo!” whispered Licani among themselves, “He looks like Franz Josef,” shouted another Lican and the entire audience laughed… “Brothers and sisters, I salute you… Let’s praise St. Sava,” exclaimed Gajo. “Long live Gajo,” yelled the Licani… The program ended around ten o’clock, and the spectators quickly got up from their chairs, which were removed to make room for dancing. The orchestra took its place on stage; a group of Sremci and Sremice gathered in the middle of the hall demanding, “Seljancica” and “Sremsko kolo,” and as the Vojvodjani were dancing, the Licani formed a ring around them watching the fancy footwork of their Serbian brothers and sisters from Vojvodina, but they could not join in, because they never saw the dance before. For an hour the Vojvodjani were dancing, and then it happened. A Lican jumped on the stage, pulled a five dollar bill out of his pocket and gave it to the orchestra not to play, ordered the Vojvodjani off the floor to make room for Licko kolo, saying, “We, too, paid the tickets to get here. We, too, want to dance;” they started the kolo such as Cleveland never saw before. One of the musicians tried to help out with the tamburitza, but without success. Licko kolo has no rhythm, no beat (similar to Crnogorci and Hercegovci). The kolo was accompanied by singing of songs from Lika. The inevitable came: those fifty voices from the strong Litani made such a thunderous noise that very few wicks survived in the lamps, the whole room trembling and swaying until the owner, Mr. Popovic, came running into the hall holding his head. “No, lads, stop it, we are all going to collapse with the building. Stop it!” Reluctantly the Licani stopped, but the leader turned around and shouted, “Let’ s go to Hamilton and dance till dawn!” All the Licani left and proceeded to dance until morning in the middle of the street.

The history of American immigration is replete with accounts of individuals of unusual fortitude who overcame incredible odds to get to America and endured great hardships in the early years of settlement. Typical of such is the story of Lazo Simic of 2153 West 20th Street.

When Simic was but three years old, his father died and his mother abandoned the family. His oldest brother, a boy of sixteen, took care of him and the four other children. When he was nine years old, Simic left home in the company of several older boys. They worked at odd jobs to sustain themselves and eventually reached Germany where they stayed for some time. In 1911 Simic sailed for New York on a false passport. On arriving he went first to Indiana to his brother’s home, then fled to Cleveland to avoid being inducted into the army. The army caught up with him and he was obliged to work for the government for a time to payoff his debt. In Cleveland, like many other single male immigrants, he lived in a boardinghouse. For more than 40 years he was a factory worker at Crucible Steel Company at West 84th Street.

Despite his many difficulties and the fact that he could neither read nor write in either Serbian or English, he made a good life for himself. He married a Polish woman and they have two children, Mary and Nick. While Simic would be the first to admit that life for the early immigrants was hard, he avows he never once considered returning to his homeland to stay. Like most of his fellow countrymen, he is proud to be an American.

Major Settlement Areas

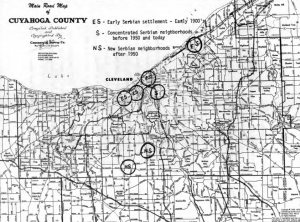

Major Settlement Areas Newcomers to Cleveland generally chose to live near their work and in areas where other Serbs were already established. Other European groups had preceded the Serbs to Cleveland and the Serbs often joined those whose language and customs were most compatible with their own.

In the earliest years, small pockets of Serbs could be found from East 26th Street to East 40th Street on Hamilton, St. Clair and Payne Avenues. Here their neighbors were Croats, Slovenes and Zumbercani. They worked mainly in nearby shops and factories, but a few owned businesses. The Zegarac grocery and the Vardar restaurant were at East 36th Street and Payne Avenue.

Further east on St. Clair Avenue near East 152nd Street, the Collinwood area, lived a number of Serbs who had found work in the Collinwood railroad yards. Earlier settlers here included Croats, Slovenes and Italians. Records for 1917-1918 of the patriotic organization, Serbian National Defense Council of America, list many Serbs with Collinwood addresses. Among them are: Amidzic, Djermanovic, Grozdanic, Stipanovic, Misic, Loncar, Djelailia, Markovic, Banjanin, Jovic, Zikic and Carico This same organization claimed a number of members from the vicinity of Madison Avenue and West 73rd Street including the families Lukin, Radic, Stanimirov, Savic, Lekic, Matic, Davidov, Tomic, Rankov and Jovanovic.

When the Republic Steel Corporation began operating in the flats, Serbs started boardinghouses along Broadway Avenue between East 30th Street and East 40th, an area which had originally been settled by the Czechs and Poles.

In time, as the Eastern Orthodox churches were erected and parishes founded, the Serbs tended to settle or relocate near them. When, in 1917, the Serbs purchased the German Lutheran church at East 36th Street and Payne Avenue and formed St. Sava’s Church, this became a Serbian center. In the 1960’s many Serbs purchased houses in Parma and Seven Hills when the new St. Sava’s Church was built at Broadview Road and Ridgewood Drive in Parma. Seven Hills and Parma were the first suburbs to draw Serbs away from the city.

Although second and third generation Serbs have scattered throughout Greater Cleveland, they continue to socialize closely with one another in political, social and religious organizations. Hundreds convene regularly for picnics at St. Sava picnic grove in Broadview Heights. Weddings, christenings and funerals continue to be occasions for large social gatherings.