Part I: History and Culture

The Nation and Its History

Dragoslav Georgevich

During the sixth and seventh centuries, the Serbs, with other Slavic tribes, entered their Balkan homeland from the north and unlike their predecessors, Visigoths, Huns, Ostrogoths and Avars, formed permanent settlements there. Since the environment is of primary importance in the creation of the culture of a nation, it is necessary to examine the structure of the region populated by Serbian people.

The Geographical Scene

The Balkans, one of three South European peninsulas, is unlike Iberia and the Apennines because it is wide open to the north. Surrounded by the Adriatic, Aegean and Black seas, it is separated from Asia Minor by only the narrow Strait of Bosporus. Throughout centuries the Balkans has been a natural land bridge between Europe and the continents of Asia and Africa.

The territory populated by the Serbian people can be divided into two large topographic regions, the lowlands and the mountains. The hills and plains including the Pannonian basin, Northern Serbia and river valleys make up the lowlands. The mountain region encompasses the rest of Serbia, Crna Gora, Bosnia and Hercegovina, Dalmatia and Lika.

The two regions differ greatly, lowland hills and plains as well as river valleys are passable, have a continental climate with hot, long summers and short but cold winters, and are suitable for agriculture. Mountain regions consist of many mountain chains with rugged, barely passable mountains, and have a mountain climate with short summers and long, cold winters unsuitable for agriculture. Mountains either are covered with forests or grass or are barren with very little vegetation. The Dinaric Mountains, parallel chains between the Adriatic and Sava River, are composed almost wholly of limestone with certain special features. There are small hollows known as kotlina, larger depressions called polje and short sinking rivers and ponds. Large surfaces composed of limestone, known in geology as “karst,” have little vegetation and water. The people in this region organize their lives around kotlinas and poljas which are suitable for agriculture. Mountains of other systems, as the Alps and Carpathians, differ greatly from the Dinaric Mountains both geologically and topographically. They offer better conditions for life since they are more densely forested, have more water and are more passable, even though there are obstacles for communication.

This configuration of the Dinaric terrain influenced the life of the population negatively in the past because it was difficult to organize political unity among Slavic tribes and clans. They lived on forested slopes, lowlands, and depressions or valleys developing individual cultures. On the other hand, these same conditions helped them survive many invasions from people outside. Invaders were never able to conquer all the mountain chains, forests, gorges or small valleys. Slavic people used their mountains as refuge in times of national emergency.

The geographical position of their land has been unfortunate for Serbs because of two main corridors or the routes which connect Central Europe with the Middle East. The first route runs from the North Adriatic along the Sava and Danube river valleys to the Black Sea. The second route is from north to south; that is, from Vienna to Belgrade and then along the Morava and Vardar rivers to the Aegean Sea. From Nis another route leads along the Nisava and Marica rivers to Constantinople. During the thirteen centuries of Serbian history, many invasions occurred along these routes. Serbian lands were invaded again and again by more powerful states, Turkey, Austria and Germany. Serbian history therefore is tragic, full of wars and struggles for survival for freedom and independence.

The Adriatic coast is precipitous for the most part. Many smaller and larger islands parallel the coast. Short rivers with many deep gorges flow into the Adriatic Sea. Most of these gorges are so steep and narrow that they are unsuitable for communications. Mountain chains and ridges of the Dinaric Alps separate the coast from the rest of the land and prevent penetration inland of the mild Mediterranean climate. These circumstances also stopped influences of Western culture from spreading beyond a narrow region along the Adriatic coast.

The Pre-Slav Period

Before the South Slavs (Serbs, Croats and Slovenes) arrived in the territory where they now live, other nations composed of many tribes occupied the Balkan Peninsula. These natives are known in history as the Illyrians and Thracians. Illyrians occupied the Dinaric region, Albania and all territory up to the Vardar River and north of Epirus in Greece. During a period from the eighth to sixth century B.C., the Adriatic coast was under strong influence from Greek merchant colonies. During the same period Celtic peoples from Central Europe infiltrated the north and northwest of the Illyrian territory. The Celts were assimilated by the Illyrians in a rather short time.

During the third century B.C. Illyrian pirates interfered with Roman commerce in the Adriatic which caused two Roman expeditions against the Illyrians. The Romans continued their wars against Illyrians for three centuries and by the beginning of the Christian era they had conquered and incorporated the whole area as part of the Roman Empire under the name of Illyricum. The area was rapidly Romanized. The administrative center of the province was in Salona, now the city of Split. The area prospered under Roman rule and Illyrians became leading Roman soldiers, administrators and even the emperors Claudius, Aurelian, Probus, Diocletian and Maximilian.

The Roman Empire was divided into eastern and western empires in 395 A.D. The line of division ran from Lake Skadar along the river Drina to the river Sava. This was broadly the line dividing the Latin-speaking part of the empire from the Greek-speaking part.

The Arrival of the Slavs

The arrival of Huns from Asia in 375 A.D. caused a great movement of nations and tribes in Europe. Illyrian lands were invaded during the fifth century by Visigoths, Huns and Ostrogoths. In 476 A.D. the Western Roman Empire came to an end and the whole Balkan Peninsula was reconquered in 535 A.D. by the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian. In the second half of the sixth century a barbarian invasion from the north devastated the whole Balkans. The invaders were the Avars who from 567 A.D. together with the Slavs raided the lands of the Eastern Roman Empire from their center in the Pannonian plain. The Avar supremacy was short lived, and by 650 A.D. the Slavs had already formed their permanent settlement in Illyria. Gradually Slavs assimilated the remnants of the Illyrians and Thracians, except for a small Illyrian group which retreated into the mountains of the present Albania.

The Slavic peoples who settled the Balkan lands were composed of three large groups. To the north were Slovenes, south of them Croats, and to the south and east of Croats were the Serbs. At the time of their arrival into the Balkans, the Slavs spoke one language with many dialects called proto-Slavic. It has been assumed by many historians that the Slavs originally settled in the area east of Carpathians between the Pripyat marshes, the Dnieper and the upper flows of the Prut, Dniester and Bug rivers. This is in today’s White Russia and Ukraine and the Slavs called it Boika.

Serbian Settlement in the Balkans

Slavic settlement in the new country occurred during the rule of the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (610-641). Serbs first settled the region of Salonika, now Greece, but since they did not like that territory. they returned back north of the Danube. Shortly afterwards they asked the emperor for new territory for a permanent settlement. They accepted the region between the rivers Lim, Piva, upper Drina, Ibar and upper flow of the West Morava. Other Slavic tribes gradually settled all territories south of the Sava and Danube. Byzantine emperors permitted Slavs to stay in their lands and named all Slavic settlements “Sklavinia.”

The existence of Serbs in their new country was endangered in the seventh century by Bulgarians who, after their arrival to the Balkans, organized a strong state and waged constant wars against Byzantium. The Bulgarian danger forced southern Serbs to organize a union in 850 under Prince Vlastimir. The Serbs recognized the superiority of Byzantine emperors and their influence led Serbs to convert to Christianity. The conversion took place between 871 and 875 mainly through the work of the two Slavic missionaries, Saints Cyril and Methodius.

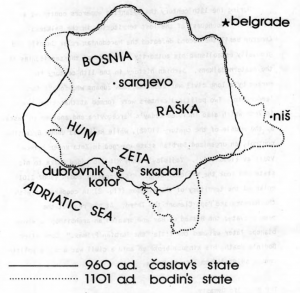

Towards the end of the ninth century Bulgarian power grew to a peak under Emperor Simeon (893-927) who conquered most of the eastern Serbian territories. Serbian chieftains or zupans in alliance with the Byzantine emperor fought the Bulgarians and liberated a large part of Serbian territory. One zupan, Prince Caslav (927-950), organized a new and rather large state which encompassed Raska, Zeta, Travunia, Hum and Bosnia (fig. 1). In the middle of the tenth century Hungarians from the north made many raids into Caslav’s territory, and in one such attack he lost his life.

During the 11th century the Byzantine emperors continued a policy of reconquest of the lost territories in the Balkans. Emperor Basil the Second defeated the Macedonian ruler Samuilo and gradually established his authority over most of the territories in the eastern Balkans. Serbian history in the 11th century is “marked by a long civil war among various zupans who fought for leadership. Two political centers were formed at that time, one in Zeta which also included today’s Hercegovina and another in Raska. By the middle of the century (1042), while Raska was under Byzantine control, an organized Serbian state emerged in Zeta under Prince Vojislav (1036-1042). Vojislav’s son, Mihailo added Raska to his state and took the title of king. His successor Bodin (1082-1101) enlarged the territory of the kingdom (fig. 2) in cooperation with the Normans and Pope Clement the Third. At his request the pope elevated the Bishop of Bar and created an archbishopric whose bishops later assumed the title lithe Serbian Primas.” Soon after Bodin’s death, his kingdom broke up amid a civil war and the political center shifted from Zeta to Raska.

The Nemanjit Dynasty

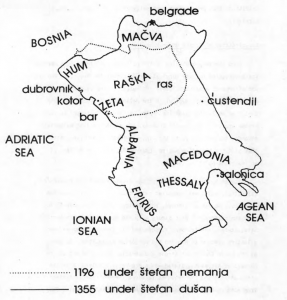

The founder of the Nemanjic Dynasty, Great Zupan of Raska Stefan Nemanja, ruled over Serbia from 1169 to 1196. He was the most important Serbian ruler in the twelfth century and his dynasty lasted more than two hundred years. It enlarged Serbian territory, organized a strong modern state and finally, under Emperor Stefan v Dusan, led Serbia to a flowering greatness in the Balkans and southern Europe. Stefan Nemanja’s youngest son Rastko, later Saint Sava, organized an independent Serbian church with the blessings of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch and the Byzantine Emperor. Other Serbian rulers from the Nemanjic Dynasty contributed greatly to the progress and strength of the Serbian state. They built beautiful churches, monasteries, and good roads, opened many mines and organized commerce.

Stefan Nemanja (1169-1196)

Stefan Nemanja shook off Byzantine suzerainty after the death of Emperor Manuel in 1180 and enlarged his state with support of the Hungarian king Bela III. He conquered Skadar, Ulcinj, Bar and Kotor. When the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick I Barbarossa entered Nemanja’s realm in 1189 leading a large European Army of 100,000 crusaders, Nemanja and his brother received him with friendship and offered an alliance against the Byzantine emperor. The crusaders continued their campaign towards Constantinople and Nemanja continued his own conquest of Byzantine territories. Even after a military defeat at the river Morava in 1190, Nemanja was able to retain most of his conquered lands. Emperor Isaak Angelo wanted a long-lasting peace and friendship with Serbs. Nemanja’s son Stefan married the Emperor’s niece Eudokia. From that time and after his abdication in 1196, Nemanja lived in peace with his neighbors. His state was in good shape and rich with many beautiful monasteries and churches which he built.

The youngest of Nemanja1s three sons, Prince Rastko, was interested in religion and philosophy. He diligently read religious books and, with great interest, listened to stories of the lives of saints told by monks from Mount Athos. When a deputation of monks visited Nemanjals court in 1192 seeking financial help, Rastko left the court and joined them. On reaching Mt. Athos and the monastery Vatoped, Rastko took monastic vows under the name of Sava. In 1197 after his abdication the Great Zupan Nemanja joined his son Sava at Mt. Athos as the monk Simeon. Father and son received permission from their relative Emperor Alexis III to build a monastery at Mt. Athos. Hilandar, their large impressive monastery, became the center from which spread a rich ecclesiastic and secular culture, the pride of Byzantium. It served the happiness and spiritual and cultural progress of the Serbian nation. The monk Simeon died at Hilandar on February 13, 1200.

Sava Nemanjic and the Serbian Church

After his father’s death Sava retreated for a time to his “Postnitza” or House of Silence in Kareia on Athos for meditation. For his distinguished life and deeds Sava was promoted to archimandrite, the highest ecclesiastical rank next to bishop. He took good care of his monastery Hilandar, wrote a constitution and bylaws for it and organized the education of monks.

Soon after the death of monk Simeon a war broke out in Serbia between two royal brothers. Vukan, the older, attacked his younger brother Stefan. Vukan had support from Hungarians who were relatives of his Roman Catholic wife. After defeating Stefan and driving him out of the country, Vukan received his royal crown from the Pope and voiced allegiance to the Papal church. Since in Hungary a fratricidal fight between the King Emeric and his brother had broken out, Vukan lost his Hungarian support and Stefan regained his throne in 1204 with Bulgarian help.

At that time fratricidal wars were common almost everywhere and Bulgaria and Byzantium were the worst. Six Byzantine Emperors died in twenty years, and not one of them a natural death. Constantinople was conquered by Latin Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade. They did not have much respect for monasteries on Mt. Athos and made frequent raids into them to plunder, steal and kill. They had completely forgotten their original goal, the liberation of the Holy Land, and devoted themselves to plunder in order to get rich.

The royal Serbian brothers Vukan and Stefan wanted a permanent reconciliation, so they asked their younger brother, Sava, to help them to restore permanent peace between them. Sava decided to do it although it would expose his two hundred monks at Hilandar to the dreadful crusaders. Sava took the body of his father, and, escorted by many distinguished monks from Mt. Athos, went to his native Serbia on a peace-making mission.

Sava‘s travel and subsequent stay in Serbia was successful because Vukan and Stefan were reconciled completely. Vukan recognized Stefan as Great Zupan of Serbia and hostilities ceased. The body of their father Simeon was kept in the monastery of Studenica and the church proclaimed Simeon a Saint. On the request of his brothers, the nobility and the mass of Serbian people, Sava decided to stay in Serbia. Great Zupan Stefan appointed Archimandrite Sava the superior of Studenica. Very soon the monastery became the sanctuary of the nation. From it Sava taught his people how to pray, believe, repent, how to be charitable and honest, and how and where to seek happiness. The people very soon felt in Sava a true friend and real shepherd; they felt that confusion and unrest for Serbia was over.

During his stay in Studenica, Sava wrote a book, The Life of Saint Simeon, one of the first Serbian literary works. He also wrote many epistles to the monks at Hilandar and other monasteries as well as letters to Serbian princes warning them about the Bogomil and Latin heresies. He continued to educate the monks in Studenica and train them for missionary work. With the help of his brother, Stefan, he started to build the Monastery Zitcha. This productive period of Sava’s life in Serbia was of utmost importance for the Serbian people. By hard, well organized work Sava fortified orthodoxy in Serbia, strengthened the authority of the church and ruler, and awoke the Serbian national consciousness.

After a short stay on Mt. Athos, Sava traveled to Nikeia in Asia Minor and visited the Byzantine Emperor Theodore Laskaris and the Ecumenical Patriarch Manuel. From them he received permission to organize “the Serbian Autocephalous Church” In 1219 Sava was consecrated Archbishop of all Serbian lands by the Patriarch and received a Grammata. During his travel through Arabic and other lands in Asia Minor, Sava was greeted and revered by people who had heard about him. He spoke perfect Hellenic Greek, delivered excellent deeply spiritual sermons and showed great charitableness. His reputation and greatness exceeded all other Serbian rulers and dignitaries. On the way back to Serbia the Archbishop Sava visited Mt. Athos, or Sveta Gora, and selected many well educated monks to go with him to Serbia.

Sava arrived in Serbia in 1220 and organized new Serbian dioceses and bishoprics. There were nine new dioceses organized in addition to the seven old ones. All the dioceses were located in monasteries, and his own seat was in the beautiful new monastery Zitcha.

The organization of the Serbian Autocephalous church was of utmost importance for Serbia and the Balkans. The Serbian king and archbishop were very moderate in the Greek-Latin church division which began in 1054. but the Serbian independent church definitely strengthened Orthodoxy in the Balkans. The creation of the Serbian Autocephalous church also strengthened Nemanjic’s Serbia by increasing connections between various groups in the country. Clerical and secular authorities were united in one religious and political entity. The church had an integrative role between the state created by Nemanja and the church created by Saint Sava. Later, when the state was destroyed by foreign powers, the church remained and the Serbian historical consciousness was preserved by church tradition, thus providing a continuity vital to Serbian cultural survival.

Consolidation of Serbia Under Nemanjics

From the very beginning of its political existence, the Serbian state struggled for its survival first against the Byzantine Empire and afterwards against Bulgaria and Hungary. The second Bulgarian medieval empire was powerful in the Balkans in the 12th and 13th centuries while the Byzantine empire was almost destroyed in 1204 by the armies of the Fourth Crusade. From 1186 to 1258 Bulgarians expanded to the west up to the line of Nis-Skoplje-Ohrid. After that time the Byzantine empire appeared again in the Balkans as an important political power.

Stefan Nemanja’s heir Stefan the First Crowned, or Prvoventani, (1196-1228) was a well educated ruler indoctrinated in Byzantine politics. He was a talented, able diplomat, cautious soldier and good administrator. With strong help and support from his brother Sava, Stefan pacified Serbia, defeated his brother Vukan and made a lasting peace with him and his Hungarian protectors. As long as the Latin Empire was strong and Venician power present at the borders of his state, Stefan was a pro-western ruler. Even the title of king and the crown he received through representatives from Pope Honorius III in 1217 were merely political acts. Soon after the Latin Empire started to weaken, Stefan turned towards Byzant. His brother Archbishop Sava, the devoted orthodox spiritual leader, crowned him in 1220 and also served Stefan as an excellent connection with the Byzantine Emperor.

King Stefan the First Crowned died in 1228 and was succeeded by his son Radoslav (1228-1233). Radoslav was both the son and husband of Byzantine imperial princesses. He was a weak ruler and completely under Byzantine influence. When his father-in-law Emperor Theodore was defeated by the Bulgarian emperor Asen II, dissatisfied noblemen overthrew Radoslav in 1233 and proclaimed his brother Vladislav king.

Vladislav (1233-1243) had full support from his father-in-law, Bulgarian Emperor Asen II, but when Asen died in 1236 Vladislav lost much of his support. In 1236 his uncle, the First Serbian Archbishop Sava, died in the Bulgarian city of Trnovo after long travel in the East. The next year Vladislav transferred St. Sava’s body to the monastery Milesevo in Serbia. In 1241 a Mongolian army passed through Serbia after defeating the Hungarian king Bela IV. Vladislav abdicated in 1243 in favor of his brother Uros.

Uros was not a particularly strong ruler but he succeeded in keeping all lands he inherited in spite of several wars against Bulgaria, Dubrovnik, Byzant and Hungary. In 1276 his son Dragutin, who had expected for quite a few years to become a co-ruler with his father, overthrew him with the political and military help of his Hungarian relative, King Vladislav.

Dragutin (1276-1282) kept good relations with his neighbors, concluded a peace with Dubrovnik and continued his father’s policy of friendship with Charles I of Anjou, the king of Sicily. Bulgaria was in a civil war and presented no danger for Dragutin. After an accident during horseback riding when he broke his leg, Dragutin decided to abdicate believing that God had punished him for overthrowing his father. He transferred his royal powers to his brother Milutin and received from his brother-in-law, the Hungarian king, Belgrade, Maeva and northeastern Bosnia as a domain. He led an ascetic life and died in 1316. Before his death he became a monk under the name Teoktist.

Milutin (1282-1321)

Milutin was one of the strongest Serbian kings, ruling Serbia for almost forty years. Following the policy of his brother Dragutin, Milutin kept good relations and concluded an alliance with Charles I of Anjou, the king of Sicily. During an Easter uprising in Sicily in 1282, almost all Frenchmen were killed. Not knowing what had happened in Sicily, Milutin attacked Byzant alone. His offensive was successful and his troops conquered Skoplje, Gostivar, Tetovo, Ovce Polje, Zletovo and Pijanec. After much combat with Byzantine and allied Tartar armies, Milutin retained the conquered territory and made peace with honor in 1299 with the Byzant. Milutin got as a wife the Byzantine princess Symonida with a dowry of all lands he already had in his possession. Later on Milutin extended his military help to Byzant in her fight against Turks in Anatolia. His Grand Duke Novak Grebostrek led a Serbian cavalry unit and inflicted several defeats on the Turks. Milutin also clashed with Dubrovnik in 1317-18 and with Hungary, but he overcame both without any serious consequences.

Milutin waged many wars against Serbian neighbors, Byzant, Hungary, Bulgaria and Dubrovnik. He enlarged Serbian territory by pushing borders southward. This was his political testament for Serbian foreign policy. The economy was strengthened under his rule. Many mines were opened, silver coins were produced and used in foreign markets and trade blossomed as never before. Milutin built 40 churches and monasteries. His court was rich and a high cultural spirit prevailed there, particularly after the arrival of Queen Symonida. Milutin made Serbia a great Balkan power before he died on October 29, 1321 at his court in Nerodimlje. He was buried in Banjska but his remains were moved to Sofia in Bulgaria by 1460 and entombed in the church Sveti Kral.

Stefan Decanski (1321-1331)

After the death of King Milutin civil disorder broke out in Serbia. Three pretenders for the throne of Serbia began fighting, two of Milutin’s sons, Stefan and Vladislav, and a son of King Dragut in. Stefan, the oldest son, had the sympathy of the people and in 1322 he was proclaimed king with his son Dusan as Mladi Kralj or “Junior King.”

Soon after his enthronement Stefan married Maria Paleolog a niece of the Emperor Andronik II of Byzant. During the fight between Andronik II and his grandson Andronik III, Stefan supported Andronik II. The grandson was victorious, so Stefan was involved in a fatal war against the Byzantine-Bulgarian alliance. The decisive battle took place at Velbutd (Custendil) on July, 28, 1330 against the Bulgarian emperor Mihailo Sisman. Serbian forces defeated the Bulgarians and Emperor Mihailo lost his life in the battle. The defeated Bulgarians asked for peace and offered Stefan a union between Bulgaria and Serbia. Stefan concluded the peace but declined the offer to unite the two states. In this battle Stefan’s son Dusan was distinguished as a great military leader. The Bulgarian ally Andronik III retreated from Serbian territory and attacked Bulgaria.

Soon after this war a struggle for power between Dusan and Stefan broke out. The cause was the succession to the Serbian throne. Stefan Decanski had another son from his second marriage to Maria Paleolog, Sinisa, and he probably wanted to make him his successor. Serbian noblemen supported Dusan and the old king was overthrown. Dusan was proclaimed king in 1331 and crowned at the state convention on September 8. Stefan Decanski died soon after he lost his throne.

Stefan Dusan (1331-46 King; 1346-55- Emperor)

Stefan Dusan, tall, robust and handsome, made a striking impression on his contemporaries. Philip Mezier, a western nobleman, wrote that Stefan Dusan was the tallest man he had ever seen. He was not only physically superb but he was also energetic, ambitious and an able ruler. He had the ability to overwhelm other men and to lead them toward his own goals.

The War with Byzant was going on. In 1334 a Byzant general, Syrgian, deserted his emperor, Andronik lIt, and joined Dusan in his conquest of Byzant territories. Dusan quickly conquered Ohrid, Strumica and Kostur and came before Solun (Thessalonike). After the death of Andronik III in 1341, civil war broke out in Byzant. Jovan Kantakuzen, co-ruler with Andronik III, was a pretender for the throne against Empress Anna of Savoy and her son. Kantakuzen offered Dusan an alliance and together they started a conquest of Byzant territories in Macedonia and Epirus. Kantakuzen was neither very successful in war nor faithful to Dusan with the result that they broke their alliance. Kantakuzen acquired a new ally in the Turkish Emir, Omar. This was a dangerous move since the Turks proved to be a new menace in the Balkans and Europe for many centuries thereafter. In addition to the war in the south, Dusan had smaller wars against Hungary and Bosnia. By 1345 Albania, Macedonia, Epirus and part of Thracia Were under Dusan’s rule. Dusan decided to proclaim his empire and proclaimed himself “Emperor of Serbs and Greeks.” II At the same time the Serbian archbishop Joanikije was proclaimed patriarch. Dusan’s wife Jelena, empress, and their son Uros, king. Other dignitaries were given such titles as despot, sevastokrator, cesar, and duke. The Serbian Empire was now a reality.

News of the Serbian Empire was not well received by Byzant. The Greek patriarch anathematized Dusan and the Serbian patriarch, but Dubrovnik and Bulgaria participated in the coronation with large delegations. The new emperor visited many monasteries and gave them rich presents of gold, lands and settlements. He visited Mt. Athos in 1347 with Empress Jelena and also gave rich donations to the monasteries there.

The proclamation of the empire clearly showed the political program of the Serbian ruler. His intention was to create a new, better and stronger state in the Balkans and Mediterranean. He immediately began negotiations with Venice for naval support in his campaign against Constantinople. He also asked the Pope in Avignon to name a “captain” for a crusade against the Turks, but his efforts were in vain because Hungarian and other western rulers were against his program. Dusan died unexpectedly of a fever in 1355 in the midst of great preparations for a march on Constantinople.

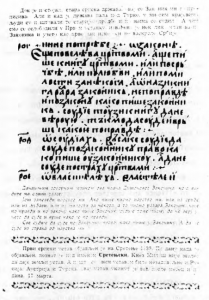

The Serbian state under Dusan achieved its largest expansion in the Balkans, stretching from the Adriatic and Ionian to the Aegean Sea. Dusan was a wise enlightened ruler. He gave his empire a new and progressive law known as Dusanov Zakonik or Code of Laws (1349) based on Serbian and Byzantine laws. One famous sentence in the code was, “If the Emperor is guilty to the peasant, the peasant has the right to accuse him to the empire.” This code, consisting of a constitution, criminal, church, and civil law, was an important cultural monument of medieval Serbia.

Disintegration of the Serbian Empire, 1355-1459

Dusan’s son Uros was a weak ruler. During his lifetime until 1371, the Serbian Empire broke into many fragments. Chieftains who were quiet and disciplined members of the empire under Dusan were able to assert their independence. The Turkish advance into Europe progressed rapidly. In 1354 Turks conquered Gallipoli, in 1360 Adrianople, then most of Thracia and Bulgaria. By 1386 a Turkish army penetrated as far as the river Neretva, but in 1388 Serbian noblemen defeated the Turks so disastrously that the Turkish commander Sahin barely escaped with his life.

Sultan Murat now came to the conclusion that he must prepare a great army in order to subjugate the Serbs. He organized an army of 100,000 men in Asia Minor and Europe composed of Turkish and vassal troops. The army was under the command of Murat and his two sons, and consisted of infantry, light cavalry and many camels. The Serbian Prince Lazar, meanwhile, organized a pan-Serbian league in order to save the Balkans for Balkan nations. However, even with allies his force of 35,000 men was numerically inferior to Murat’s huge army.

Battle of Kosovo, 1389

The Turkish and Christian armies met June 15, 1389 on the Field of Kosovo (Field of Blackbirds). A bloody battle lasted almost all day. In spite of their numerical supremacy the Turks were in a precarious position at midday when the Serbian nobleman Vuk Brankovic repelled the attack of Turkish left wing and progressed toward the Turkish center. During the melee a Serbian nobleman, Milos Obilic, killed Sultan Murat who was inspecting the battlefield. However, the battle was won by Murat’s son Crown Prince Bajazit, who used a Turkish light cavalry reserve at the right moment. The Christian army was defeated and the flower of Serbian aristocracy fell in the battle. Lazar was captured during the combat and beheaded before the dead body of Murat. Turkish casualties were also heavy, so Bajazit was anxious to return to Asia Minor in order to fortify his power and restore his army. The quick Turkish retreat gave the impression in the West that the Christian army had won the battle.

The battle of Kosovo was fateful for Serbs because, although their state did not cease to exist, it became a tributary to the Turks. Lazar’s son Stefan and his mother Milica concluded a peace with Bajazit in which Lazar’s daughter Olivera became Bajazit’s wife and Stefan became his vassal. Thus he was obliged to participate in Bajazit’s wars with his 10,000 cavalrymen.

A great cycle of legends known in Serbian poetry as “The Cycle of Kosovo” followed the battle at Kosovo. Each year on June 28, Serbs commemorate Vidov-dan. Gusle music and folk singers have kept alive the fate of Serbian heroes up to the present. Those poems are among the best of that kind in world literature and have been translated into all major languages. Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic was cannonized as a saint by the Serbian Church under the name of St. Lazar of Kosovo. His body was preserved and is now kept in the Serbian cathedral in Belgrade. Murat I is also revered by Moslems. His body is preserved and buried at Brusa, while his entrails are buried at Kosovo in a small mosque known as “Muratovo turbe” which still exists.

lazar’s son Stefan ruled Serbia from 1389 to 1427. He.was a wise ruler, courageous soldier, precocious politician and patron of art and literature. During the life of Sultan Bajazit he was loyal to him, but in the beginning of the 14th century Bajazit was entangled in a war against Tamerlane, Emir of Samarkand. In 1402 Bajazit was defeated by Tamerlane in a great battle at Ankara. After that time Despot Stefan decided to instigate a new foreign policy of friendship with the Hungarian king Sigismund. He acquired Belgrade (1404) and transferred his capital there. During his 38 years reigning over Serbia, Despot Stefan united under him many provinces which had been under the rule of other minor Serbian noblemen. Stefan’s foreign policy was successful because he was able to use both the Turks and Hungarians to his advantage.

After Stefan’s death the Turks conquered the largest part of Serbia and in 1459 they captured the last Serbian fortress of Smederevo. With the fall of that stronghold the last Serbian hope for an independent state fell. The next Serbian state, Bosnia, fell soon after in 1463 and, with the exception of a tiny refuge in Crna Gora (Montenegro), all Serbs lost their freedom. Europe was occupied with its own small wars and disputes and did not have time to fight the Turks. Serbian states and Serbian rulers had fought the Turks for more than a hundred years from the death of Emperor Dusan (1355) until the fall of Smederevo (1459). Of all the European countries, only Hungary took an active part in the fight against the Turks.

After the fall of the Serbian despotate (1459) and the fall of Bosnia, the Turks continued their invasions into Dalmatia and Hungary. Constant war forced the Serbian populace to emigrate to the West and North. Serbian masses populated Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Srem, Banat, Backa and even Erdelj and Vlaska. Serbian aristocracy spread allover Europe, but the largest number remained with the people in Hungary to continue its struggle against the Turks. This resistance was insufficient to detain the Turks since Hungary was already weak. In 1526 Sulejman the Magnificent defeated Hungarians at Mohac and occupied Hungary. The Hungarian nobility elected the Austrian emperor, Ferdinand of Habsburgh, as their king. Austria, now, was in the first line of combat against the Turks.

Serbs Under Turkish Rule

From the battle at Mohac in 1526 throughout the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, Austria and then Russia were at war with the Turks. With the Kucuk-Karnejdzi peace treaty in 1774 Russia acquired a right to protect all Christians in Turkey. The Serbian people under Turkish rule suffered much in such situations. They joined Christian powers in the struggle against Turks and were repeatedly abandoned by them and exposed to Turkish revenge.

Turkish rule in Christian lands was oppressive but not intolerable, for Serbs had some independence in their local administration. Also the Turks were tolerant in matters of religion. The Serbian Orthodox Church and its followers had better treatment from Turks than they could have expected from their Roman Catholic fellows. In 1557 the Turkish Grand Vizir, Mehmed Sokolovic, concluded an agreement with the Serbian church according to which the Serbian patriarchate was organized to encompass all Serbian lands under Turks. The first patriarch of the restored Serbian Church was Makarije Sokolovic, brother of the Grand Vizir. This event was of enormous importance for Serbs since, even without their own state, they were united through their church. Patriarch Makarije was an excellent administrator and organizer. Serbian bishops visited their dioceses and monasteries, consoled their people, and encouraged a high spirit and hope for better days in the future.

Gradually Serbs came to the conclusion that they could acquire their freedom only by their own efforts. Throughout 350 years of occupation Serbs kept their traditions and nationality through their folk songs and stories. Blind IIguslarsll sang about Nemanjics, about Dusan, Lazar, Kraljevic Marko and the heroic Serbian struggle for freedom throughout centuries. Without schools or books Serbs transferred their oral literature from one generation to another through poems and stories. Whenever Turkish tyranny and oppression became unbearable, the most courageous men among Serbs went to the woods and mountains, organized guerrilla units and attacked Turks. They were known as hajduks and uskoks. The Serbian fighting spirit and hope were constantly growing as the time for liberation was approaching.

Serbian Struggle for Liberation

At the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century Serbs felt that the time for liberation arrived. In the spring of 1804, Karadjordje Petrovic (Black George) rose up against the Turks. With minimal Russian support Serbs fought the Turks for eight years and, after many bloody battles, defeated them. However, the political situation in Europe with Napoleonic wars was unfavorable for the Serbs and their uprising against the Turks collapsed in 1813.

Their failure to achieve independence did not discourage the Serbs and in 1815 Milos Obrenovic started the second Serbian rising against the Turks. More battles followed this fateful event. From that time up to 1918 the Serbs fought for their liberation.

In 1912 Serbia concluded the Balkan Alliance with Crna Gora (Montenegro), Greece and Bulgaria in order to liberate all Christians in the Balkans who were still under Turkish rule. In two major battles at Kumanovo and Bitolj, the Serbian army decisively defeated the Turks. Armies of Crna Gora, Bulgaria and Greece also defeated Turks in other battlefields. The Turks were expelled from the ancient Serbian lands, Old Serbia and Macedonia. Then a dispute about the new borders resulted in another war in 1913 in which Bulgarian armies attacked Serbs and Greeks. The Bulgarians were soon defeated by Serbs, Greeks and Romanians, but the Turks reoccupied Jedrene and a part of Thracia.

Austria-Hungary was now unhappy with the Serbian success which elated the Slavs under her rule. Serbia and Crna Gora cooperated closely and that was dangerous for Austro-Hungary. Clearly little Serbia was blocking Austro-German expansion to the East as well as causing racial and national problems for the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. That government first tried to contain Serbia by using various political and economic means such as a custom war and threats. On facing stiff Serbian resistance it made the fatal decision to withstand Serbia militarily in a preventive war.

The immediate cause for aggression was the attempt on the life of the Austro-Hungarian Crown Prince Ferdinand and his wife on June 28, 1914 by an Austrian subject, Gavrilo Princip, a young Bosnian Serb. The Austrian government cast blame for the attempt upon the Serbian government and submitted an ultimatum to Serbia. The content of this ultimatum was such that no sovereign state could accept it. After thorough consultation with the allied governments of Russia, France and Great Britain, the Serbian government decided to reject the Austrian ultimatum; consequently Austria declared war against Serbia.

Military operations against Serbia began on July 28, 1914 with a bombardment of Belgrade. Thus World War I began. The Russian Emperor Nikholas II warned Austria to cease operations against Serbia; Germany invaded Belgium, attacked France and addressed an ultimatum to Russia; and Great Britain, a French and Russian ally and guarantor of Belgium neutrality, declared war with Germany.

Serbia in World War I

When the Serbian Government rejected the 1914 ultimatum, Austro-Hungarian troops were ready for a “penal expedition” against Serbia. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was one of the strongest countries in Europe. It had the best territory in the heart of Europe, 36 million inhabitants, a strong well-trained army, an excellent bureaucracy, firm traditions, an able diplomacy, and a war industry able to produce contemporary armaments. But its troops which consisted of Slavic elements were unreliable.

Against a heterogeneous Austria-Hungary composed of 15 nations stood the spiritually united, small but tough Serbia. the Serbian king, Petar I Karadjordjevic, was a democratic ruler beloved by his people and respected by foreigners.

While Serbia’s morale was very high, her material preparedness for this war was inadequate. Ammunition was spent in the Balkan wars, weapons were worn ‘out and her finances were less than good. The first Austro-Hungarian offensive against Serbia ended in defeat. The Austro-Hungarian Fifth Army was badly beaten and forced to withdraw across the Drina River. After this first Austrian attack the Serbian government issued the “Nis Declaration” stating that the Kingdom of Serbia would continue fighting until final victory over Austria-Hungary and liberation of all South Slavs.

The second Austro-Hungarian offensive, during which Serbs were forced to abandon Bel grade and other territory because of an acute lack of ammunition, also ended in disaster for the Austrians. They were badly defeated, losing 50,000 prisoners and a large amount of war equipment to the Serbian army.

In the fall of 1915 the third enemy offensive began. Serbia was attacked from the west, north and east by the Austro-Hungarian, German and Bulgarian armies. Serbian” resistance was persistently strong, but Serbs were overwhelmed and retreated toward the south and the Adriatic coast. From there allied navies evacuated remnants of the army to the Greek island of Corfu. Out of 300,000 men about half survived the great retreat.

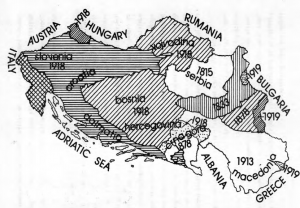

In September 1918 Serbian and French troops supported by British and Greeks broke through the Thessalonike front and Bulgaria capitulated. Serbian troops then made one of the fastest pursuits known in modern history. They liberated Belgrade on November 1, having crossed 500 kilometers in 45 days with continuous fighting. In one month all lands populated by the South Slavs were liberated and Austria-Hungary fell apart. Vojvodina proclaimed unification with Serbia on November 25 with Crna Gora following the next day and then most of Bosnia-Hercegovina. On December 1, 1918 the Serbian Prince Regent Alexandar received a delegation of the Yugoslav National Council. The delegation asked the regent for unification of all Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in a new state. Regent Alexandar responded promptly and proclaimed the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Crna Gora

Serbian tribes which populated the territory of the present Crna Gora organized their tribal states as early as the 9th century. At that time Crna Gora had the name Zeta. In 1077 Prince Mihailo Voisavljevic organized a stronger state which encompassed a number of surrounding regions. He was the first king of this Serbian state. His successor, Bodin (1081-1101) enlarged the kingdom, but after his death the state broke up amid civil war.

In the era of the Nemanjic dynasty Zeta was governed by the Serbian crown princes with the capital at Skadar. In the 15th century a new dynasty was established by Stefan Crnojevic. His son, Ivan the Black, was a fierce warrior who had fought the Turks all his life. In 1493 Ivan established the first printing press in Obod which printed the first books in Cyrillic characters. Ivan also built a monastery at Cetinje and made it a bishopric. During his rule the name of the state changed to Crna Gora (Montenegro). Turks forced him to become their vassal and Ivan, the last Crnojevic, accepted Islam under the name Skender-beg. He governed both Crna Gora and Albania, but after his death in 1528 the Turks attached Crna Gora to the district of Skadar. In the 17th century Venice tried unsuccessfully to put Crna Gora under her reign. Crna Gora remained under the Turks with autonomy and a vladika (bishop) as head of state. The tribes were ruled by their chieftains who had such titles as serdar, vojvoda or captain.

When in the beginning of the 18th century Russia acted as protector of all Christians in the Balkans, Vladika Danilo I Petrovic established relations with the Russian emperor Petar the Great. Danilo was dissatisfied with the state of affairs in his domain because some of his subjects had adopted Islam and had given support to the Turks. On Christmas Eve 1702 a wholesale massacre was ordered, an event known as “istraga poturica” (extermination of Turkish converts). This event, with the many bloody battles which followed, did not result in freedom for the Serbs of Montenegro. The Turks subjugated the uprisings of 1712 and 1714, and, from that time until 1851, Montenegro was ruled by its bishops. They kept connection with Serbia and Russia and worked for the recovery of their national consciousness. The last bishop-ruler was Petar II Petrovic Njegos, a philosopher and poet with a pan-Serbian and pan-Slavic feeling. His capital work was Gorski Vijenac. After his death in 1851 his nephew, Danilo II, not wanting to be bishop, was proclaimed Prince of Montenegro with Russian support. Turkey opposed this act and started preparations to invade Montenegro, but Russia with other powers prevented a Turkish invasion. When in 1875 Serbs in Hercegovina led by Luka Vukalovic revolted against the Turks, Serbia and Montenegro declared war against Turkey.

In 1860 Danilo II died after being shot by. an outlaw, and, since he had no son, his successor was his nephew Nikola. An able ruler and skilled politician, Nikola I reigned over Montenegro until 1914. He married his daughters to Russian princes, Serbian king Petar I Karadjordjevic and Italian king Victor Emanuel III to secure friends in European courts.

Crna Gora Under Nikola I

After the wars of 1876-77 Crna Gora lived in peace. Her economy slowly grew and important social and political changes took place. Roads were built, post offices were opened, a bank was founded, agriculture was improved, many elementary schools were opened and an agricultural college was founded in Podgorica. A theatre, museum and public library were opened at Cetinje. In 1906 Crna Gora had over a hundred primary schools, two secondary schools and about ten thousand pupils. For higher education students were sent abroad, mostly to the University of Belgrade.

Internal political development was equally important. In 1915 a parliament was established, and in 1910 Nikola I took the title of king. Because of his relations with the Serbian, Russian, Italian and German royal families through the marriages of his daughters, Nikola was described as “the father-in-law of Europe.”

In all the Serbian wars for liberation in 1876, 1877, 1912, 1913 and 1914 Crna Gora participated against Turkey, Austria-Hungary and Germany as an ally of Serbia. In all those wars Crna Gora expanded her territories and enlarged her population. When in 1915 Serbia was occupied by the central powers, Crna Gora too was occupied and in 1918 Crna Gora proclaimed her union with Serbia.

Serbs in Macedonia

Macedonia is the geographical region between the river Mesta on the east, the Aegean Sea to the south, Lake Ohrid to the west and the mountains Sara and Kara Oagh to the north. In the 14th century the whole of Macedonia was part of the Serbian empire. Emperor Stefan Ousan made Skoplje his capital. After the battle of Marica in 1371 the Turks gradually conquered Macedonia and after the battle of Kosovo it was in Turkish possession. By 1430 the whole of Macedonia together with Salonica was firmly in Turkish hands and it was held by them until the Balkan wars of 1912.

The Turkish regime in Macedonia was as suppressive as in other Balkan lands. There were two classes of people, the Ottoman chiefs as landowners and the peasants. Local Turkish governors gradually became independent while central power declined in the 17th and 18th centuries. Lawlessness in that part of the Ottoman Empire became so great in the 18th century that the big European powers intervened in order to protect Christians. By the Kucuk-Karnejdzi agreement of 1774, Russia was acknowledged protector of all Christians who belonged to the Patriarchate of Istanbul. In 1839 the Sultan issued a decree which proclaimed the equality of all races and religions within the empire. The Paris agreement of 1856 recognized the right of the big European powers to interfere with Turkish reforms, but despite all interventions, the situation of the people was not improved.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Bulgarian nationalism awoke and pressed the Turkish government to grant a separate Bulgarian church under an exarch. Jurisdiction of that Bulgarian church autonomy extended over the whole of Macedonia and included also the towns Pirot and Nis. The Treaty of San Stefano which created Great Bulgaria in 1876 was rescinded by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878, but the Bulgarian exarchate was left untouched. The Bulgarian government strongly supported the exarchate and opened many Bulgarian schools in Macedonia. Two Bulgarian bishops were appointed, one in Skoplje and one in Ohrid, so the Bulgarian influence increased.

The Serbs strongly opposed this Bulgarian action in Macedonia which for them was ancient South Serbia. At the Berlin conference the Serbs had claimed that region, but in vain. However, later in 1881, the Serbian king Milan Obrenovic received Austro-Hungarian support for Serbian expansion toward the south. King Milan promised that Serbia would discourage any agitation in Bosnia and Hercegovina. Serbian influence in Macedonia advanced very well after that time. By 1900 there were 800 Bulgarian and 180 Serbian schools in the districts of Kosovo, Bitolj and Salonika. The Greeks also organized over 900 schools in districts of Bitolj and Salonika.

The Bulgarians also gave refuge to terrorists. Their Internal Macedonia Revolutionary Organization aimed at securing Macedonian autonomy. Since their propaganda did not gain support of all the Christian population, Bulgarians organized bands of “comitadjis” who started to wage guerrilla warfare against the Turks. Bulgarian armed bands also terrorized the population forcing them to become Bulgarians or pro-Bulgarian. Serbs retaliated by organizing their own guerrilla units, and the Greeks followed the Bulgarians and the Serbs. Terrorist activities broke out over all three districts. The Turks retaliated sharply, so this irregular warfare depopulated and destroyed many villages.

In October 1903 Austria and Russia proposed to the Sultan a plan known as “Murzsteg Progranme.” Two civil agents, one Russian and one Austrian, were attached to the Turkish Inspector-General. Five European powers took control over five different sectors of Macedonia. This attempt failed and the guerrilla activities were renewed. In 1908 a group of Turkish officers, the so-called “Young Turks,” revolted against Sultan Abdul Hamid, deposed him and proclaimed the equality and brotherhood of all subjects of the Ottoman Empire. As a result, the great powers abolished international control of Macedonia and withdrew the officers of gendarmerie from the five sectors of Macedonia.

The Young Turks proved to be nationalistic and in favor of centralization of Ottoman power. Macedonia again became the scene of murder and plunder. Such developments in the Ottoman Empire drew all Balkan countries together. In 1912 Serbia and Bulgaria concluded an alliance; Greece and Crna Gora followed them and a strong Balkan alliance was formed which forced the end of the Turkish rule over most of their European domains. After five centuries ancient Serbian lands with fine monuments of medieval Serbian culture were joined to the Serbian national state. Macedonia was divided among the Serbs and Greeks. Since Bulgaria was excluded from this position, during World War I she joined the Central Powers hoping to gain control over Macedonia. Defeated in 1918, Bulgarians awaited a new favorable moment to fulfill that aspiration. In 1941 Bulgaria received all of Serbian and Greek Macedonia from Hitler, but after . his defeat by the Allies she lost all of it again. In 1941 Yugoslav Communists created a new nationality and a new Macedonian language and separated the “Macedonian church” from the Serbian church.

Vojvodina

The provinces Banat, Backa, a part of Baranja and Srem have been known as Vojvodina since 1848; Slavs populated that region for the first time in the fifth and sixth centuries during the Hun invasion of Europe. In the ninth century the Hungarians created their state and this region became part of it. The settlement of Serbs into Vojvodina was continued throughout centuries but it was substantially increased in the 15th and 16th centuries after the fall of Serbia. At the end of the 15th century Hungarians permitted Serbs to organize an autonomous region ruled by Serbian despots. They encouraged Serbs to settle in this region to serve as a bulwark against Turks who were making plundering raids into Hungary.

During the Austrian-Turkish war in the 17th century after the Turkish defeat at Vienna, the Serbs were instigated by Austrian propaganda to rise up against the Turks and participate in the war on the Austrian side. The Austrian offensive was stopped by the Turks at Kacanik and they were forced to retreat. The Serbs who feared Turkish revenge withdrew to the north. The organizer of this large migration of 60,000 families was Patriarch Arsenije III Carnojevic. The abandoned Serbian lands of Kosovo and Metohija were settled by Albanians. Patriarch Arsenije III asked and received a guarantee from Emperor Leopold that Serbian religion and church autonomy would be respected. However the Hungarians did not always adhere to that agreement. The Serbian struggle for religious and later secular autonomy lasted throughout all of the 18th century, but without success.

In the revolutionary year of 1848 when Hungarians led by Lajol Kostur rose up against the Habsburgh dynasty, Serbs together with Croats under Jelacic fought against Hungarians in support of the Austrian emperor. In May 1848 the Serbs elected Josif Rajacic their patriarch, Stevan Supljikac their military leader and proclaimed Serbian Vojvodina. The emperor promised them autonomy but did not keep his word, for in 1849 he appointed an Austrian general as governor. In 1860 Vojvodina was completely abolished and remained in the Austro-Hungarian empire until 1918 when the Serbian army defeated Austria-Hungary and liberated it. On November 21, 1918 the Great National Assembly of Vojvodina proclaimed its union with Serbia. After many centuries under foreign rule the Serbs of Vojvodina became part of a Serbian national state. Although Serbs form a majority in Vojvodina there are other national minorities as Hungarians, Romanians, Germans and Slovaks. This mixture of various nationalities is a result of the Austrian policy of “first divide then rule.”

Cultural Life in Vojvodina

Although under foreign rule, Serbs in Vojvodina had rather favorable conditions for their cultural development. Agriculture was progressive and commerce flourished in the Austrian Empire. A substantial number of Serbs in Vojvodina were wealthy people who supported education, religion and art. A main role in the Serbian cultural development in Vojvodina was played by the literary association “Matica srpska” (Serbian Queen Bee) which was established in 1826 in Budapest by rich Serbian merchants. Since 1863 the association has been in Novi Sad and regularly publishes “Letopis Matice srpske” (Chronicle of Serbian Queen Bee). This magazine still publishes literary works written by Serbian authors for Serbian people.

Serbs in Vojvodina have always been in close connection with Serbs in Serbia proper: During the Serbian wars for liberation their help to the insurgents was great both in armament and in services of educated men. They helped the Serbian government to organize its own administration, schools, post office, telephone and telegraph. Their contribution to the whole Serbian nation was great. They produced famous authors, painters, composers, university professors and scholars. A native of Vojvodina was Mihailo Pupin, world famous physicist and professor at Columbia University in New York, as well as an outstanding inventor in the field of electrical engineering.

Serbs from Vojvodina strongly supported the Serbian church. From 1690 the seat of the Serbian Orthodox Patriarch was in Sremski Karlovci and all Serbs under Austro-Hungarian rule recognized the Patriarch as their spiritual leader. The Serbian Patriarchate did much to preserve the Serbian national consciousness and prevent Magyarization.

Military Frontier

After the fall of Serbia. the Turks continued their raids into Hungarian lands. The whole 15th century was marked by the Hungarian struggle against the Turks. In 1526 at Mohach the Hungarians were disastrously defeated, their king was killed and their resistance came to an end. Hungarian and Croatian noblemen elected the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand of Habsburg their ruler in 1527. From that time on he and nearly all succeeding Austrian emperors waged perpetual war against the Turks. The land was devastated and depopulated by constant Turkish raids. Austrian military authorities decided to organize a special region, the Military Frontier, (popularly called Kordun) to serve as a bulwark against the Turks. The region was gradually populated by people with special privileges and certain obligations. They held their land without any taxes but in return they voluntarily accepted the obligation of rendering military service to the empire. In 1557 .the Austrian Archduke Charles of Styria (Steiermark) built a fortress at Karlovac on the river Kupa and he became the first commandant of the Military Frontier. In 1578 the whole region from the Adriatic Sea to the Drava River was named the Croatian Military Frontier (fig. 4). this region was a land of fortifications, watchtowers and guards. Its inhabitants were free peasant-soldiers who were obligated to bear arms and fight Turks from the age of 16 to 60. Among other ethnic groups the Austrian military commanders invited also Serbs to settle in this region. They accepted the offer and settled there in large numbers. They had the privilege of electing their own mayors and judges. After the great Serbian / immigration into Hungary under Arsenije III Carnojevic in 1690 Emperor Leopold reorganized the Military Frontier into regiments, battalions and communities. The number of Serbs in the Military Frontier was particularly large in the 18th century when Serbs composed half of the Austrian army.

Croatian and Hungarian feudal lords did not like to have Serbs in Military Frontiers. Serbs were not subject to their feudal taxes, their jurisprudence or their church hierarchy. They were the emperor’s soldiers and had more freedom than Croatian and Hungarian peasants. Those feudal lords as well as the Archbishop of Zagreb fought Serbian privileges at all levels of the Austrian administration. However the emperor was their protector since he needed soldiers for his wars. Serbs had many problems with their Austrian military commanders. Many of them behaved as sole owners of the land and requested taxes; discipline was brutal, pay was low and often not on time. However, Serbs fought successfully for their privileges because the Habsburgh emperors continued their protection.

In the 18th century Empress Maria Teresa who was under pressure from Hungarians and Croatians joined the largest part of the Military Frontier to Croatia and Hungary. In 1881 the region was finally abolished and incorporated under Hungarian administration. Serbs have continued to live in the regions of the former Military Frontier up to the present day, always successfully defending their rights and their existence.

Serbs in Yugoslavia

After December 1, 1912, for the first time in history, all Serbs were united in one state with other South Slavs. From its very beginning, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes had difficult problems. One initial problem was the political issue of centralism versus federalism. The new state had been created from two independent Serbian states, Serbia and Montenegro, and from territories which had been under Austria-Hungary. The South Slavs were inexperienced in the complicated democratic machinery of modern state politics. The Serbs of Serbia and Montenegro, although having been subjects of constitutional and parliamentarian monarchies, did not have the needed political experience to rule a large country consisting of several other nations. Other Slavs who had been under Austria-Hungary had been in the opposition and against the state and its authorities for several centuries. Economically speaking, Yugoslavia was predominantly an agricultural country with 85 percent of the populace employed on the land. It was rather rich in natural resources, but underdeveloped in comparison with the West European countries.

The three major religions –Serbian Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Moslem –were not very tolerant of each other. Nationality problems were also complex. There were those who considered themselves Yugoslavs; others were hoping for independent countries of the major nationalities of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia. While most Yugoslavs spoke Serbian-Croatian, the Slovenes had their own language and national minorities spoke Hungarians German or Albanian. To make it even more complex, the Slovenians and Croatians use the Latin alphabets while the Serbians still use the Cirilica, similar to the Russian alphabet.

Before the constitution was even voted on or implemented the Serbian and the Croatian politicians argued sharply over two ideas. The Serbs were for centralization while the Croats were for a confederation. The Croats wanted a republican system while the Serbs had been monarchists from the very beginning of their history. They had a victorious army which participated in World War I on the side of the Entente; they had their national dynasty and bureaucracy, and a homogeneous population the largest in number of all partners in the new state.

The first constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs Croats and Slovenes was accepted in 1921 by a vote of Serbian, Slovenian and Moslem deputies. The Croats abstained. According to the constitution, the state was an integral, centralized, parliamentarian and constitutional monarchy. The Croats refused to participate in the work of the National Assembly (Skupstina) from 1921 to 1924. In 1924 they made an agreement with the Radical Party and their participation in the government was secured. Unfortunately, in 1928, during a long, bitter and unrestrained debate in the National Assembly, the deputy Punisa Racic killed two Croatian deputies and mortally wounded Stjepan Radics president of the Croatian Peasant Party. The Croats again left the Assembly in open defiance of the government.

Seeing that the parliamentarian system had failed, King Alexandar I suspended the constitution in January 1929, and following the advice of political leaders, formed a caretaking government. Political parties were dissolved, the National Assembly was abolished and the name of the state was changed to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Although the king’s act was labeled ” royal dictatorship” by many westerners, King Alexandar was never an autocrat. He always regarded himself as “a guardian but not a source of the power, the servant and not the lord of the people.” Two years after, the king promulgated a new constitution which did not mollify the Croats. In 1934, during a state visit to France, King Alexander was assassinated.

After his death, the Regency, headed by Prince Paul, reached an agreement with the Croats, creating an autonomous Croatian Banovina headed by a governor and with its own national assembly.

Although Prince Paul’s main idea in foreign policy was to keep the country out of war, there was much dissatisfactibn with him. In 1937 he signed pacts of friendship with Bulgaria, Italy, and in 1941 the fatal pact with the Axis (Germany) in order to avoid war. Dissatisfaction with the Regency and the Government after Yugoslavia’s adherence to the Tripartite Pact resulted in a military coup d’etat. The Regency was overthrown and the young Prince Petar II was made king. The Serbian people received the news of change in government with mixed feelings, but mostly with sympathy. Croats were for peace and against the putsch, while the Slovenes were neutral.

As a consequence of this change of government, Hitler decided to destroy Yugoslavia in spite of assurance by the new Yugoslav government that adherence to the Tripartite Pact would be respected. On April 6, 1941, German, Italian and Hungarian troops invaded Yugoslavia. The resistance of Yugoslav armed forces was insignificant. The troops were not fully mobilized yet and the air force was quickly destroyed by superior German air power. German troops quickly penetrated into Yugoslav territory and, at the same time, attacked Greece.

The Yugoslav government and King Petar escaped from Yugoslavia to Greece by airplane.

Occupation, Resistance and Civil War

The collapse of Yugoslavia was so rapid that the Serbian peasants called it “The April confusion.” About 250,000 Serbian officers and soldiers were captured and taken to Germany and Italy as prisoners of war. A considerable number took up side arms and light armament and went to their homes in the mountains, determined to start a long and merciless guerrilla war against all enemies. This was a centuries-old Serbian tradition and nobody was able to prevent it.

Draza Mihailovic and Josip Broz

In May 1941, a general staff colonel, Dragoljub (Draza) Mihailovic, who refused to recognize the capitulation of the Yugoslav army, appeared at Ravna Gora in Western Serbia. Many armed groups immediately recognized him as their commander in chief. The Yugoslav government in exile promoted him to general and appointed him Minister of Defense. General Mihailovic started a thorough organization of his guerrilla units, called chetniks, and ordered selected attacks and sabotage against occupation forces.

After Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the Yugoslav Communist Party also started action against Germans. The leader of this action was the Secretary General of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz –Tito. His guerilla units were known as partisans. The two guerrilla groups had different objectives. General Mihailovic primarily wanted to save the Serbian people from possible extermination and therefore favored attacking Germans only when needed. His plan was to preserve his forces for the end of the war and then to inflict a decisive blow to the enemy. Tito, on the other hand, favored immediate take over of the occupied lands.

Because of these armed actions, Germans made many terrible reprisals. For every dead German soldier, they shot up to 100 hostages. The German commanding general in Serbia offered a reward of a hundred thousand reichmarks in gold each for Mihailovic and Tito. On orders of the Yugoslav government in London, Mihailovic had two meetings with Tito. Their cooper at ion was short lived, and by the end of 1941, chetniks and partisans were in a bloody civil war which cost many thousands of lives. In 1941 and 1942, the Western Allies recognized and supported only Mihailovic. He and his chetniks were glorified in Great Britain and the United States as the first insurgents in occupied Europe.

From 1942 on, this external and fratricidal revolution, one of the worst in human annals, decimated the Serbian population. In the meantime, domestic and foreign Communists began an effective campaign in support of Tito’s guerrilla units. Mihailovic was attacked as a German collaborator and by 1943, the Allies switched their support and military aid to Tito.

Having secured military support from allies, Communists enjoyed a favorable poltical situation for their ascendance to power in Yugoslavia. On October 20, 1944, troops of Soviet General Talbukhin entered Belgrade and with them Tito came to power in Yugoslavia.

In March 1945, a regency and a new Yugoslav government were formed. Tito became Prime Minister and Minister of Defense. Many Serbian leaders opposed the new regime, including Mihailovic, and were arrested and sentenced to death with the help of the so-called people’s courts. When the Communists did organize elections in November, there was no opposition to them. The newly elected Constitutional Assembly abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. According to the new constitution enacted in January 1946, Yugoslavia was divided into six republics: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina, Crna Gora, Serbia and Macedonia. Thus, the Serbian people were divided among several republics.

Between 1946 and 1948, resistance to the Soviet type communist regime and Soviet domination became so strong, even within the Yugoslav courts, that the government was forced to relax the pressure toward nationalization of land and Soviet dependence. This in turn provoked Stalin and other leaders who accused Tito and Yugoslav Communists of deviation from their basic doctrines. In 1948, the Cominform expelled Yugoslavia from the society of the socialistic community. Economic sanctions followed, isolating Yugoslavia from the rest of the Communist world. In this situation, Tito turned to the United States for economic aid. The American government decided to help the country with food, money, armament and the education of Yugoslav military and civilian personnel. The purpose of this policy of “calculated risk” was to preserve the independence of Yugoslavia. The relations between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia were poor until 1956 when the Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev visited Belgrade and established friendly contacts.

Life for Serbian people in Yugoslavia is not free. Criticism of the regime and the society is forbidden. Although religion is permitted by law, there are many restrictions which fetter the freedom of religious practices. Christmas, for example, is not a holiday so employees must work on that day. Serbian national holidays are outlawed. City people cannot celebrate St. Sava’s Day, St. George‘ s Day, Vidov-dan or their Slava (Patron Saint of the House). However, villagers have more freedom in that respect. Consequently, the Serbian village is once more, as in the past, the guardian of Serbian customs, traditions and culture.