Part One. Their Paths are Peace: Verdant Symbol

Ancestry and Beginnings

Witnesses to a great American city’s earnest belief in the application of the principles of human brotherhood, Cleveland’s Cultural Gardens, mirroring the cultural backgrounds of a highly diversified population have steadfastly served as mute, but moving and eloquent spokesmen for the purposes set forth at their dedication more than a quarter of a century ago.

Extending along a mile of wooded hillside, bordering Doan Brook, between Superior and St. Clair Avenues, in Rockefeller Park, the gardens are a product of the united efforts of the Cleveland Cultural Garden Federation, the City of Cleveland and the Federal Government.

World peace, through mutual understanding, is the message they bespeak, and mankind’s eternal hope for the dawn of an era of brotherhood in action as well as belief.

Cleveland’s cosmopolitan citizenry, linked in this effort, has written a message in trees, shrubs, and pathways as a setting to monuments to some sixty world cultural figures, whose inner significance and meaning have not been submerged by the garb of glowing beauty that the years have brought to this unique and notable municipal and civic achievement.

The garden chain now embraces the American Garden, the American Legion Peace Garden of the Nations, the American Legion Peace Garden of the States, the Irish, Hebrew, Shakespeare, Hungarian, German, Ukrainian, Greek, Italian, Slovak, Rusin, Czech, Yugoslav, Lithuanian and Polish Cultural Gardens, each and all, dedicated to the great basic ideas contributed national cultures upon which out civilization and our American democracy are founded.

The Cultural Garden declare today, as they did at their founding, that faith and hope, rooted in past heritages, are the realities of the future.

Cleveland had a Shakespeare Garden ten years before the Cultural Garden development came into being. The establishment of this garden in 1916, the year of the 300th anniversary of the death of Shakespeare, suggested to Leo Weidenthal, Cleveland newspaperman who had been active in the Shakespeare commemorative event, that is cultural project standing alone, failed to present the entire picture, a panorama would be enfolded to stand as a symbol of democracy and brotherhood.

Due to the vision and untiring efforts of the late Charles J. Wolfram, who was to serve as president of the Cultural Garden Federation for twenty-five years, and Mrs. Jennie K. Zwick, civic leader and the Federation’s first executive secretary, the project safely surmounted earliest visionary stages and gradually assumed shape and being. In this transition, the City of Cleveland, then under the guidance of William R. Hopkins as city manager, played an active and far reaching part. City Manager Hopkins became interested in the project in its formative stage and was instrumental in securing aid for its development.

That Cleveland was prepared for such an enterprise and awake to its possibilities and meanings, was due, in large measure, to two organizations which had been formed for purposed of good-will and civic cooperation among citizens of various national backgrounds. One of these, the Civil Progress League, destined to become the immediate predecessor of the organization later formed for the direct purpose of promoting the Cultural Gardens, was founded in 1925. with Charles J. Wolfram as president, Leo Weidenthal as honorary president, Mrs. Jennie K. Zwick as executive secretary, Anton Grdina as treasurer and Mrs. Anna Mokris as recording secretary and historian. It was a federation of nationality groups whose purpose was to foster the spirit of good will and fellowship among men, to weld harmony among Clevelanders of diverse origin, and to promote citizenship.

The other group, with a strikingly similar purpose, was the American Equality League, many of whose organizers were active in the Civic Progress League and later in the establishment of the Cultural Garden League.

The purpose of the American Equality League, as set forth in its Constitution, was to create and promote a spirit of brotherhood, helpfulness and cooperation among all American people without regard to race, creed or origin, with a profound reverence for the Constitution of the United States of America and its institutions.”

Because of this feeling of friendship and goodwill among the various groups of Cleveland, .the task of the earliest organizers and promoters of the Cultural Garden enterprise, was lightened in no small degree. When the new development occurred in the life of the Civic Progress League, there was no break.

The Cultural Garden League, succeeding the Civic Progress League, came into being in the year 1926 with Charles J. Wolfram as president, Jennie K. Zwick as executive secretary, Mrs. Anna Mokris as secretary and Leo Weidenthal as honorary president.

As successor to the Civic Progress League, the newly established body thus stated its four-fold aim “to encourage friendly intercourse, to beautify our city parks, to memorialize our culture heroes and to inculcate appreciation of our cultures.”

The Shakespeare Garden had long since become an established city institution when the pioneers began their task of bringing reality to the Cultural Garden idea. Creation of the first garden unit organization was undertaken by Mrs. Zwick and it was an historic moment in the life of the League, when Chaim Nachman Bialik, hailed by Hebraists as the true successor to Judah ha-Levi, visiting Cleveland as guest of honor, on May 5, 1926, planted three Cedars of Lebanon at the future site selected for the Hebrew Cultural Garden.

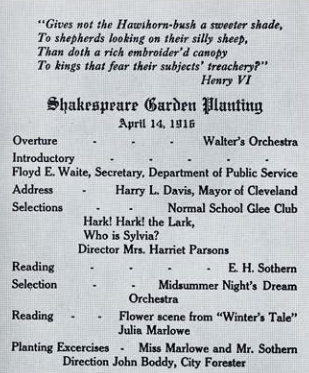

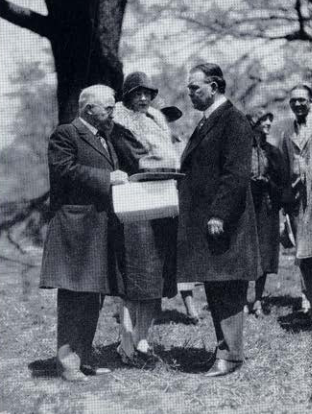

While this was the earliest formal recognition of the project, under the garden chain plan, in reality, there was an ancestral ceremony at the dedication of the Shakespeare Garden site, April 14, 1916, when the renowned Shakespearean actress, Julia Marlowe and her husband, the famed actor, E. H. Sothern planted American elms, marking the place selected as the entrance to the then yet-to-be Shakespeare Garden.

Miss Marlowe chose as her contribution to the program, a reading of a portion of the flower scene from Shakespeare’s “Winter’s Tale”. Cleveland, under the spell of her reading, became a spot near the “Seacoast of Bohemia” with Perdita extolling in Shakespeare’s richest phrases, the glorious beauty of the flowers that fell from the hands of frighted Proserpina in the dim mythland of long, long ago. Official city recognition of the Cultural Garden? of Cleveland, became a reality on May 9, 1927 with the passage of the following ordinance by the Cleveland City Council:

“An ordinance to set aside a part of Rockefeller Parkway for sculptural tributes to poets and other cultural leaders, and for special landscape and garden development.

“Whereas, the department of parks in the City of Cleveland in the year 1916, for the purpose of commemorating the 300th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, did lay out and establish a garden now commonly known as the Shakespeare Garden in Rockefeller Parkway;

“Whereas, atvarious times since 1916 there have been planted in said Shakespeare Garden, trees and other plantings of great sentimental and historical value, which have materially enhanced the attractiveness and beauty of said garden and made it a feature of the city park development;

“Whereas, upon tracts adjoining said Shakespeare Garden there has been constructed a gateway in memory of the late Marie Brnot and an out-door theatre, and in addition thereto, a series of plantings have been grouped that will serve as a nucleus of a Hebrew Garden in Rockefeller Parkway; now, therefore,

“Be it ordained by the Council of the City of Cleveland;

“Section I. That in view of the improvements heretofore installed and now existing in Rockefeller Parkway, and with a view to perpetuating the sentimental and historical associations thereby established, all that portion of Rockefeller Parkway lying between Superior Avenue on the south and Parkway Hill east of the lower drive on the north, be and the same is hereby designated The Poets Corner.

“Section 2. That said The Poets Corner be subdivided into units and that the following named units are located and bounded as descried n the following sections.

“Section 3. Shakespeare Garden: That portion Rockefeller Parkway lying east of the upper drive and between North Boulevard and Est 98th Street shall be designated The Shakespeare Garden.

“Section 4. Shakespeare Garden Theatre. That portion of Rockefeller Parkway between the upper and lower drives and bounded on the north by a line 25 feet northerly from and parallel with the main axis of the Shakespeare Garden, extended westerly; and bounded on the south by a line 330 feet southerly from said northerly boundary line and parallel therewith shall be designated the Shakespeare Garden Theatre.

“Section 5. Hebrew Garden. That portion of Rockefeller Parkway between the upper and lower drives bounded on the north by a line 330 feet southerly from and parallel with the main axis of the Shakespeare Garden, extended westerly and bounded on the south by a line 860 feet southerly from and parallel with the northerly boundary line last above described shall be designated the Hebrew Garden.

“Section 6. This ordinance shall be in force and take effect from and after the earliest period allowed by law.”

The ordinance became effective June 19, 1927.

The Poets Corner in later years was to become The Cultural Gardens, and one of the earliest developments, the Shakespeare Garden Theatre, named in the ordinance, though it was the scene of a beautiful presentation of Shakespeare’s “Mid-Summer Night’s Dream” in 1926, the occasion being a feature of the celebration of the one hundredth anniversary of Western Reserve University, came into gradual disuse because of technical presentation difficulties. The Bruot Gate, erected in memory of L. Bruot, for many years, teacher of English speech and director of many school productions of Shakespeare plays at Central High School, still forms the lower Boulevard entrance to the Shakespeare Garden.

With the development of the Hebrew Garden came the other links of the Garden chain in rapid succession. The Italian, German, Slovak, Polish, Hungarian, Czech, Lithuanian, Jugoslav, Rusin, Irish, American Legion Peace Garden, American, Ukrainian and Greek Gardens came into being in the immediate years following the acceptance of the development plan.

In many cases, their progress was speeded by unlooked for aid from a new source. The explanation of this and the story of developments of the succeeding years are reserved for later chapters.

These, as did the beginnings, reveal the patient effort and the zeal of the devoted band of Cultural Garden pioneers and later workers and the steady backing of city administrations that have stood by the enterprise with true understanding and sympathy.