Part Two. Links in the Chain: History of the Cultural Gardens

Shakespeare Cultural Gardens

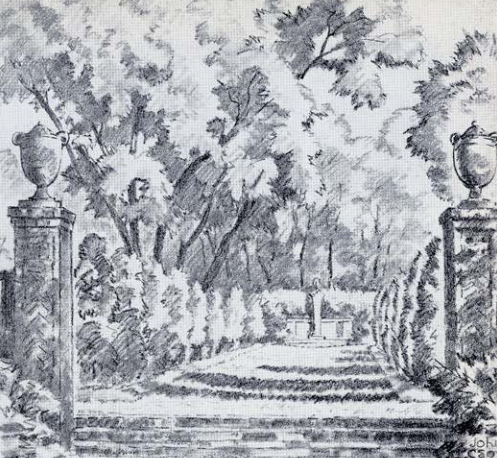

The Shakespeare Garden, ancestor of the Cultural Gardens, is Elizabethan in mood and pattern.

At the entrance are gateposts of English design and the garden boundaries are defined with hedges. The central flagstone walk is lined with multi-hued border planting, and, together with the other herb-bordered paths, converging on a bust of Shakespeare flanked by trees. A mulberry tree grows here from cuttings sent by the late Sir Sidney Lee, famed Shakespearean critic, from the mulberry, Shakespeare himself planted at New Place, in Stratford. In addition to elms by E. H. Sothern and Julia Marlowe, the garden is adorned with oaks planted by the Irish poet, William Butler Yeats, and by Phyllis Neilson Terry, niece of Ellen Terry; a circular bed of roses (Shakespeare’s favorite flower) sent by the Mayor of Verona, from the traditional tomb of Juliet; Birnam Wood sycamore maples transplanted from Scotland, and several other representatives English forest trees. The Byzantine sundial was presented by the distinguished actor, Robert Mantell. Also formerly included were jars played with ivy and flowers by Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Rabindranath Tagore–the “Shakespeare of India”–and Sarah Bernhardt.

The garden plot laid out under the direction of City Forester John Boddy, and was copiously planted with hawthorns, daffodils, violets, fleurs-delis, daisies, pansies, and columbine– the flowers given immortality in the poetry of Shakespeare.

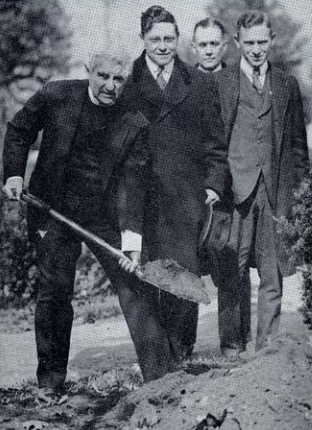

The Shakespeare Garden inaugural exercises took place on April 14th, 1916, the tercentenary year, on the upper boulevard near the garden entrance. E. H. Southern and Julia Marlowe were guests of honor. After speeches of welcome by the city officials and May or Harry L. Davis, the orchestra played selections from Mendelssohn’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and the Normal School Glee Club sang choral setting of “Hark, Hark, the Lark” and “Who Is Sylvia?” A group of high school pupils in Elizabethan costume escorted the guests to the garden entrance and stood guard during the planning of the dedicatory elms. In his formal talk, Mr. Southern urged story-telling days for children in public parks. Miss Marlowe climaxed the proceedings by her reading of Perdita’s flower scene from “Winter’s Tale,” the 54th Sonnet of Shakespeare, and the verses from the Star Spangled Banner. Her leading of all present in the singing of the National Anthem brought the impressive event to a close.

A limestone bust of the poet, the work of Joseph Motto and Stephen Rebeck, preceded a bronze bust, recently placed in the garden. Speakers at the formal dedication of the bust, recently placed in the garden. Speakers at the formal dedication of the bust on October 21, 1916, were Alex Bernstein, director of public service, William Raddatz, organizer of the Shakespeare Memorial Committee and president of the Cleveland Advertising Club, and Judge Willis Vickery, Shakespeare student and collector.

Willows flanking the fountain dais were planted by William Faversham and Daniel Frohman. Vachel Lindsay, planted a poplar and recited his own Shakespeare tribute. Novelist Hugh Walpole also planted a tree here. Notable joint visits to the garden were those of Edwin Markham, author of “The Man With the Hoe,” and Aline Kilmer, widow of the soldier poet, Joyce Kilmer, in 1919; and of the actor, Otis Skinner and the humorist, Stephen Leacock. David Belasco came to plant two junipers, and Effie Ellsler, whose early triumphs occurred on the stage of Cleveland’s Academy of Music, planted a maple near the Mantell sundial. Jane Cowl, during her Cleveland “Juliet” engagement, planted an elm near Juliet’s rose-bed. Two eminent Cleveland writers, Edmund Vance Cooke, poet, and Carl Robertson, nature writer, also planted trees.

The entrance gate, giving access to the upper hillside garden from the lower boulevard, was erected in 1925 as a memorial to Marie Leah Bruot, a teacher at Cleveland‘s Central High School. It symbolizes her long service as a gateway to Shakespeare appreciation for many Clevelanders. The stone and iron gate was designed by City Architect Herman Kregelius. George Barber headed the memorial committee.

In 1926 the renowned Shakespeare mulberry was enclosed by a circular bench donated by the Shakespeare Society, and dedicated on the poet’s birthday by the Federation of Women’s Clubs.

On June 15th and 16th, 1926, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” was presented by members of the drama clubs of Western Reserve University, in a natural amphitheatre formed by the slopes between the upper and lower boulevards. Ethel Barrymore planted the key hawthorn of the bushes set out as a stage background.

On June 13th and 14th of 1936, “The Tempest” was given by the Baldwin Wallace College Players of Berea, under the auspices of the Daughters of the British Empire, and jointly sponsored by the Cultural Garden League and the Parks Department of Cleveland.

Since 1931 the Daughters of the British Empire have been the active Shakespeare Garden group, with Mrs. G. W. Mercer as leader. Notable tree plantings under their sponsorship included a tribute to the Bicentennial of George Washington on May 24, 1932; a planting in honor of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, on the 125th anniversary of his birth, August 6, 1934; a seedling from the Royal Forest, England, received May 12, 1937, commemorating the coronation of the late King George the Sixth, father of the present Elizabeth the Second; an English oak planted by Audrey Wurdemann Auslander, great great granddaughter of Percy Bysshe Shelley. In 1941, Alfred Noyes, author of the popular poem, “The Highwayman,” Viscount Halifax, British Ambassador to the United States, and Sir Philip Gibbs, British journalists, all planted oaks here in the Shakespeare Garden.

On the memorable Sunday afternoon of September 1, 1935, the Sir Edward Elgar Chapter of the Daughters of the British Empire, under the direction of Mrs. Vera Newstead Rowley, held a meeting in the Shakespeare Garden. Garden lovers from all over the city were invited to a tour of the Gardens. A program of Morris dancing by literature students of Cleveland College, excerpts from Shakespeare’s plays, and biographical sketches by members of the Lakewood Little Theatre Guild were presented.

On May 28, 1948, the Royal Oak sapling grown from the 1937 Coronation seedling was planted by Cornelia Otis Skinner, who, on a visit to Cleveland, had expressed a desire to see the tree planted in the Shakespeare Garden by her famous father, Otis Skinner.

In July of 1951 the 25th anniversary of the Cultural Gardens was celebrated with a public, conducted tour of the Garden chain. Guests included many out-of-town members then attending the National Library Association convention, being held in Cleveland at that time. Also, a boulder was unveiled b? Dr. Luther Evans, Librarian of Congress of Washington, D. C., in the Forest of Arden section of the Shakespeare Garden, bearing a passage from “As You Like It”:

“Books in Running Brooks,

Sermons in Stones,

And Good in Everything.”

The Shakespeare Garden was laid out during the mayoralties term of Harry L. Davis, and while Alex Bernstein was director of city parks. Floyd Waite and Harry Hyatt, as park director and city forester respectively, succeeded them in this service. Considerable expansion took place during the administration of City Manager William R. Hopkins, when Frank S. Harmon was park director and Arthur L. Munson was city forester. Features added at this period included a rock garden background for the Shakespeare bust, the setting out of the Birnam Wood grove, and the extension of the garden area to the Bruot gateway. The active personal support given by City Manager Hopkins to the entire Garden project cannot be overestimated. Councilman. E. Smith gave it energetic support at its outset, and served as committee chairman of the tercentenary event. Glenville High School also gave active backing.

“England‘s sea wall has not confined his restless vision,” wrote Leo Weidenthal of his favorite poet in his book, “From Dis’s Waggon,” “Shakespeare as gardener sings the loftiest strain.”

The dedication of the Shakespeare Garden was auspicious, for it proved to be the seedling from which was to spring the flourishing garland of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens.