Main Body

Chapter 2 The Emerging Community Development System

A community development “system” in Cleveland, as opposed to a series of programs and projects, came together in the early ’80s due to a number of factors: the collapse of federal support for cities, emergence of a public-private partnership during the Voinovich years, growing unrest and activism in Cleveland’s neighborhoods, banking and corporations seeing that neighborhood needs had to be addressed to achieve business objectives and social peace, and finally, local foundations realizing that new forms of collaboration were necessary to address funding needs and capacity requirements in the emerging neighborhood agenda.

Nationally, the Reagan Administration of 1981 to 1989 cut cities adrift, adopting an anti-urban, neocon approach that viewed government-run programs as the problem, not the solution. Tax rates for the wealthy were slashed (the Laffler curve scam that lower tax rates would increase tax revenue), and defense spending accelerated. From 1981 to 1992, inflation-adjusted federal aid to cities was cut by 60 percent; appropriations for Housing and Urban Development- subsidized programs fell more than 80 percent, mostly taking the form of Section 8 rental subsidies (rental vouchers for low-income folks paid to private landlords). Federal aid to cities relied heavily on block grant allocations and stimulating private-sector investment.

This retreat on the federal level coincided with the election of George Voinovich, an ethnic Republican career politician who, after two terms as Cleveland mayor (1980-89), became governor of Ohio and a US senator. He defeated populist Dennis Kucinich by pledging an end to civic strife with a pro-business partnership that would benefit residents. Key to his agenda was a heavy dose of civic boosterism (“The Comeback City; Cleveland’s a Plum”), subsidies for downtown projects, and working more closely with foundations and nonprofit organizations to advance civic priorities.

Voinovich was heavily supported by the Greater Cleveland Growth Association (essentially the long-term regional Chamber of Commerce) that focused on directing public subsidy and services toward downtown redevelopment.

In Cleveland, tax abatement, $100 million in federal Urban Development Action Grants (UDAG ) loans for downtown projects, and a renewed emphasis on a public-private partnership was key to Cleveland emerging as “The Comeback City.” One result of this partnership was an agreement between Cleveland Trust and a consortium of local banks to roll over bond repayment that had triggered the city’s default in 1978 and to loan an additional $20 Million to help restructure its financial position. Another initiative called for recruiting local business to modernize the city’s operations and administrative systems to improve the city’s bond rating and accountability. Key to this effort was an audit, followed by an Operations Improvement Task Force chaired by Cleveland business executives, which resulted in the city adopting Total Quality Management operations guidelines. As impressive as this reorganization looked on paper, the reality was that budget and operations ran through George Forbes, an old-school politician who managed appropriations to reward his friends, punish his enemies and preserve the council ward system with himself as council president.

Although the acclaimed partnership lacked a formal agreement with terms and performance measures, it nonetheless led to formation of a plethora of volunteer, nonprofit civic organizations, supported by local foundations and corporate donations. These were expected to advance a shared city agenda by providing resources, early planning and private-sector expertise.

The Cleveland Roundtable (now the Greater Cleveland Partnership) was formed in the early 1980’s to deal with race relations and minority enterprise. At the same time, Cleveland Tomorrow, organization of the top 50 corporations and their CEOs, and since absorbed into the Greater Cleveland Partnership, were two illustrative examples. At the neighborhood level, banks joined boards of newly formed community development corporations, and CEOs participated in foundation-sponsored organizations like Neighborhood Progress, Inc.

One result of this new partnership approach was the Lexington Village Apartments housing development in the Hough neighborhood. The Hough Uprising led to a rapid exodus of people and business and left behind a devastated landscape of vacant lots and buildings, with little in the way of social capital or new investment. For 20 years nothing positive had happened. The elementary school at Lexington Avenue and East 76th Street, the area of the 1966 riots, was demolished, leaving a three-acre vacant lot. Sister Henrietta Goris and Bob Wolf, leaders of the Famicos Foundation, a faith-based community organization, approached Steve Minter of the Cleveland Foundation and Councilwoman Fannie Lewis about developing low-income housing on the site. They acknowledged the scale of the project and said it required an experienced developer who could manage both development challenges and property management. No local builder with the needed capacity was interested. They recruited McCormack Baron Salazar of St Louis to develop what in 1987 came to be a 277-unit housing estate in 17 buildings that became a catalyst for future market-rate housing development.

According to Joe Roman, president and CEO of the Greater Cleveland Partnership, “The 1980s was a critical time. A lot of people think the big housing move in Cleveland started downtown. I don’t. In many ways, housing in the neighborhoods was really ahead of the Warehouse District and downtown generally.” It began in Hough.

Lexington Village required a combination of public subsidy—UDAG grants, tax abatement, cleanup funds, infrastructure money—as well as bank financing, foundation grants, and program-related investment loans. Minter took the lead in securing the $13 million needed to build the first phase of the project, with support from 27 public and private partners. Based on this experience, he realized the time and effort needed to successfully manage a project of this scale. If replicated in numerous neighborhoods, there would have to be a system that could handle this level of development citywide.

Neighborhoods on the Move

Neighborhood conditions were rapidly declining in the late ’70s: vacant houses proliferated, arson was up, public services were down, and the banks were redlining and closing their branches. Supported by the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland, the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, and National People’s Action (NPA), a nonprofit co-founded by disciples of community organizer Saul Alinsky in Chicago, a coalition of neighborhood advocacy groups emerged. These included Citizens to Bring Back Broadway, the Buckeye-Woodland Community Congress, St. Clair Community Coalition, Near West Neighbors in Action and others. The groups built on a network of block clubs and neighborhood centers like Merrick House in Tremont or local parish churches like Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in Detroit Shoreway. The staff were VISTA volunteers, New Left veterans, and local activists like Chris Warren, who went on to become Community Development Director for the city of Cleveland. A range of other grassroots folks later came to occupy leadership positions in the city over time.

The Alinsky model focused on winnable demands and disruption to get the powers that be to the table. In Cleveland in 1981, 600 neighborhood activists picketed the elite Hunt Club soiree for Alton Whitehouse, the chairman of Standard Oil of Ohio (Sohio), and disrupted the annual Sohio stockholder’s meeting. When British Petroleum acquired Standard Oil of Ohio, the corporate memory of such events influenced subsequent support for community development activity. As BP America CEO James Ross stated, “I don’t believe that BP can exist as a wealthy company in a society where you have such a substantial underclass as you do in Cleveland that will pull the whole structure down with it”. (See page 160 in Keating, Dennis W., Norman Krumholz, and David C. Perry, eds. Cleveland: A Metropolitan Reader. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1995.)

Local organizing combined with a series of Community Reinvestment Act challenges protesting the failure of local banks like Society and Central National to meet the credit needs of neighborhoods. Activists also targeted East Ohio Gas demanding an end to utility shut offs and support for home weatherization programs. Union Miles Community Coalition and others also targeted the Veterans Administration for its home mortgage lending and its failure to maintain foreclosed properties. In addition, housing activists like Phil Star and Ray Pianka had begun to organize a citywide campaign leading to creation of the Cleveland Housing Court, which is instrumental in defending tenant rights and maintaining housing standards. (Pianka, who had been director of the Detroit Shoreway CDC and became a city councilman, went on to serve several terms as Housing Court judge.) For an in-depth view of community organizing in Cleveland from 1975 to 1985 see Randy Cunningham’s account, Democratizing Cleveland.

Democratizing

Seeing that organizing alone wasn’t enough to reverse decline and improve neighborhood housing, the community coalitions formed development affiliates in the St. Clair, Slavic Village, Tremont, Ohio City, Detroit Shoreway, Buckeye, Cudell, Glenville and Fairfax neighborhoods. Boundaries of newly formed CDCs often overlapped ward boundaries. Operating support came from respective City Council ward allocations and small grants from the Cleveland, Gund and Sohio Foundations.

Early staff for these newly formed community development corporations were social activists committed to grassroots organizing and neighborhood empowerment, like Chris Warren, Bob Pollock at Near West, Pat Kenney in Buckeye, Bob Hudecek at St. Clair, Rob Curry and Tony Brancatelli in Slavic Village, and myself in Union-Miles. As the CDCs grew and the supporting infrastructure expanded, another generation of professional staff with advanced degrees in law, finance and business played important roles in bringing the neighborhood redevelopment efforts to scale.

However, in the early days, on-the-job training was the norm, with local support from the Center for Neighborhood Development at Cleveland State University’s Levin College of Urban Affairs and national support from Joe McNeely and the Development Training Institute, with rehab assistance from Ray Mikelthan and Jim Larue at the Lutheran Housing Corporation. The Cleveland Housing Network with Bob Wolf at Famicos and Chris Warren at Tremont became the umbrella for the nascent CDC industry and pioneered a lease-purchase model for rehabbing vacant properties for low-income families.

Despite these advances, the scale of neighborhood work was still relatively modest— 50 renovated houses a year citywide—and CDC capacity, both financially and organizationally, was fragile. Local foundations began to look at a new model for building local capacity. It was based in part on the Lexington Village experience and the Ford Foundation’s work with local partnerships in leveraging resources for more scale and impact. The Cleveland Neighborhood Partnership Program (CNPP) was one outcome of the search for new funding models.

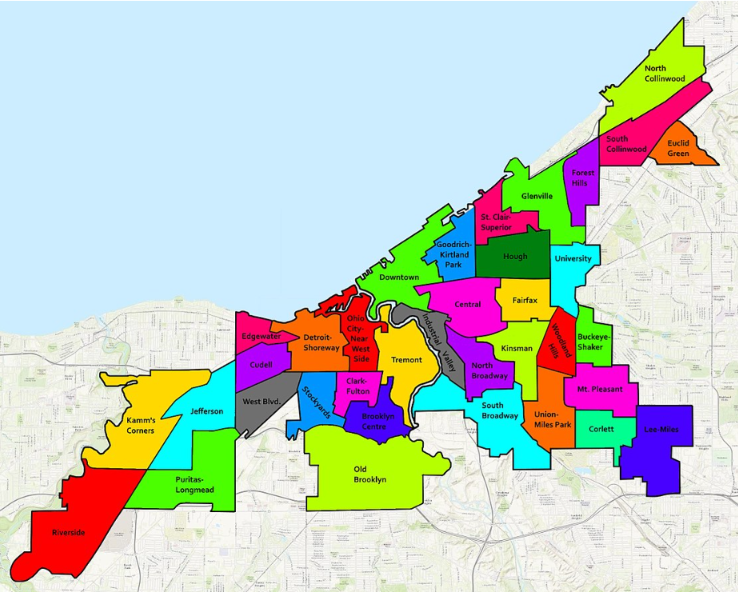

Cleveland Neighborhood Map Image Source: From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neighborhoods_-_Cleveland.jpg, under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License

My Story: The Early Period—Union-Miles

In 1982 I was living in the St. Clair neighborhood with my wife Carolyn Platt when I heard from an organizer for the St. Clair Community Organization that a new community development corporation in Union-Miles, a working-class, African- American neighborhood in southeastern Cleveland, was looking to hire its first executive director. The organization had grown out of the Union-Miles Community Coalition where Ken Esposito, Ann Pratt and Marita Kavalec had organized block clubs to demand better city service and protest neighborhood disinvestment by Society Bank and the VA’s redlining and property maintenance record. After a successful Community Reinvestment Act challenge, Union-Miles activists had gotten Society Bank to support a development corporation and provide financing for neighborhood projects. Steve Minter of the Cleveland Foundation had given them an operating grant. They meant business.

I applied for the job. I thought it was a good fit. I lived in a multiracial Cleveland neighborhood, had been a Job Corps counselor and Teamster organizer, could do issue organizing, write a leaflet, chair a meeting, listen to the room, and negotiate a contract. I had worked as a union carpenter and knew something about construction. I didn’t know anything about nonprofits, fundraising or finance, but I had a lot of energy, good intentions and organizing skills. I was a white guy, but not a racist (or so I hoped).

I now realize how lucky I was that the Union-Miles board took a chance with me. The heavy lifting had been done: the grassroots organizing, the planning, the clear sense of purpose, and the resources required to bring the neighborhood back, were all in place. Leadership of the Union-Miles Development Corporation (UMDC) was critical. Inez Killingsworth, a neighborhood resident and a forceful spokesperson for the community, was Board chair. A service worker in the city school district and a local leader of National People’s Action, she, along with other residents, kept the bankers at the table and made sure the organization was responsive to the community. The Board had reps from Society and Central National banks, and the city councilman Earle Turner, but most members, like Hugh Kidd, Thelma Wilson, and Vera Coe, were residents active in their block clubs. There were no local businesses or church pastors represented. This lack of institutional muscle would later be a problem when economic conditions deteriorated.

During my time at Union-Miles, we successfully renovated a handful of homes for sale in an environment of 17-percent interest rates, developed an exterior home repair program using area youth, re-developed a mixed-use historic building to preserve the last family drugstore (Cermak) in the area and provided rental apartments on the floors above. This was one of the first low-income tax credit projects in the City in which Pat Costigan at CSU (later of the Enterprise Foundation) played a pivotal role in structuring the financial model based on corporate investment from Standard Oil.

We also worked with Mary Ann Simpson at CSU’s Center for Neighborhood Development, coming up with a novel approach for obtaining title to vacant houses as a court appointed receiver. UMDC secured funding from the Cleveland Foundation to develop a pilot program that could be replicated

and used to support state wide receivership legislation. Working with the newly created Housing Court, UMDC requested to be named receiver for an abandoned home in our target area, first making need repairs to address health and safety issues. (See picture.) We then proposed to take title to the property by foreclosing on the receivership lien. The newly created housing court approved our request. Dr. David Listokin of Rutgers University wrote a book on the topic that looked at national examples of receivership programs and drafted model legislation for us. With this in hand, we went to State Senator Troy Lee James and then-state representative Lee Fisher to introduce legislation for a state-wide law. Working with the Ohio CDC Association (of which I was the vice-chair) we successfully got the legislation passed and signed by Governor Dick Celeste.

The idea that a community group could successfully pass a state-wide law that gave community groups a mortgage lien position in front of a bank is quite remarkable. It speaks to changes in the political environment, but also the potential of bottom-up initiative supported by philanthropy.

In all these activities at UMDC, a sense of possibility, energy and collaboration permeated the emerging community development landscape in Cleveland. That sense also informed my own later work.