Main Body

Chapter 3 Neighborhood Progress Inc.: A New Approach to Community Renewal

In 1985, the Cleveland, Gund, and BP foundations realized that a new approach was needed to support the emerging community development field. They then created the Cleveland Neighborhood Partnership Program (CNPP) to explore a collaborative funding model for community development. This pilot program, modest in scope and budget, was to test if an intermediary approach was politically viable, operationally effective, and likely to increase the level of neighborhood investment and impact.

The Ford Foundation agreed to launch this program with a grant of $350,000 contingent on a local commitment of $700,000. Based on a citywide request for proposals, six emerging CDCs received two-year operating support averaging $85,000 for a CDC project manager, planning, and operating overhead needed to develop high-impact projects. In addition, the Ford Foundation made a 10-year, $2 Million, 2% program-related loan to supplement bank financing. A program manager from the CDC community was hired—me—and Cleveland Tomorrow, a newly formed corporate leadership organization, agreed to be the fiscal agent and provide administrative support. The hope was that this exposure to neighborhood revitalization would lay the groundwork for future corporate engagement.

A committee of foundation staff, Cleveland Tomorrow, the City Council President and the Cleveland Community Development Director selected the six diverse neighborhood grantees and provided program oversight.

In addition to operating support CNPP helped identify and recruit local developers for CDC projects and held workshops resulting in “Shop Talk,” a how-to guide for neighborhood real estate development. Consultants also worked with grantees to strengthen financial management and board governance, laying the groundwork for ongoing support. To bring banks to the table to lend to neighborhood housing ventures and with only one professional staff, CNPP used the Ford Foundation PRI loan for compensating loan deposits to provide below market financing for sponsored projects.

At the end of the first year, CNPP’s performance was favorably evaluated by Ed Skloot of New Ventures, a New York City-based consultancy. A study by James Pickman and Associates, commissioned by the Cleveland Foundation, recommended that the Foundation expand its neighborhood focus to develop middle-class housing and new commercial centers, with greater coordination of community development investments by local foundations.

The foundation staff that worked with Cleveland Tomorrow on the initial proposal to create a new foundation intermediary (Neighborhood Progress, Inc.) was senior, knowledgeable about best practices in the field and effective advocates internally. Jay Talbot of the Cleveland Foundation had previously been with the Ford Foundation’s “gray areas” program, a comprehensive anti-poverty effort in New Haven; Dan Berry of the Gund Foundation and Lance Buhl of BP America were equally experienced and helpful. Leadership of both Cleveland and Gund Foundations—Steve Minter and David Bergholz respectively—had significant first-hand community development exposure, Minter with Lexington Village and as Welfare Director for the State of Massachusetts. Bergholz from Pittsburgh had been deputy director of the Allegheny Conference (a model for Cleveland Tomorrow) and a senior executive with Action Housing, both nationally recognized civic organizations. Foundation staff played an active role in ensuring its success. Not only did they help structure proposals to ensure they aligned with foundation expectations, but they also nurtured Foundation board champions for the agenda and later served on NPI grant making and loan committees.

Cleveland Tomorrow

Cleveland Tomorrow was a newly formed organization (1985) of Cleveland’s 50 largest headquarter companies. The strategy developed by Mckenzie Company called for CEO leadership to participate directly in a limited set of Cleveland Tomorrow priorities and a range of affiliated organizations. The agenda focused heavily on downtown and tourism, regional economic data, the Cleveland Advanced Manufacturing program, Playhouse Square, and neighborhood revitalization. A key expected outcome was shaping public policy and government funding decisions to support Cleveland Tomorrow priorities. Surprisingly, neighborhoods made the list. Not a top priority, but still. . .

So why did Cleveland Tomorrow agree to act as fiscal agent for CNPP and later as a funding partner? I believe a mix of factors figured in their decision. The public/private partnership as a means of realizing social objectives was very much in vogue in the Voinovich era and the foundations wanted to engage corporate leadership in a broader civic agenda. Cleveland Tomorrow wanted to have a voice in how an organization it might affiliate with was structured, especially since its member CEOs might be directly engaged. This was especially true for the banks, which were looking at community reinvestment issues, and BP/Sohio, needed to be viewed as a good citizen as it located its new headquarters in Public Square. The fact that many of the headquarter bank banks were in the process of consolidation through mergers and acquisitions and needed to demonstrate in the Community Reinvestment Act environment that they were meeting the credit needs of Cleveland neighborhoods. Serving on the NPI Board lending to CDC projects, and tax credit investments contributed to a favorable CRA assessment. In addition to corporate Realpolitik, Cleveland Tomorrow staff believed in the neighborhood strategy and wanted to see it work.

It should be noted that missing from this corporate leadership group were the non-headquarter companies (e.g., auto and steel) as well as the CEOs of the universities and hospitals in the city whose operations had a significant impact on Cleveland neighborhoods.

Neighborhood Progress, Inc.—A Foundation Operating Intermediary

Based on the favorable assessment by Ed Skloot and recommendations from James Pickman for the Cleveland Foundation came a proposal in 1989 from Cleveland Tomorrow for a new 501 (c) 3 organization—Neighborhood Progress Inc. (NPI)—to manage an operating grant support program, technical assistance, and real estate finance for community development corporations in the city.

The name for the newly formed organization was not chosen after a carefully considered strategic planning session but was more a shared understanding that the agenda required more than a program and an ad hoc funding partnership, that progress was a reasonable goal and that including Inc. in the name would indicate a business approach likely to be more favorable viewed by the banks and private investors.

Followed a two-year, $4.2 Million aggregate grant request to the Cleveland, Gund, Standard Oil later BP, Ford, and Premier Industrial foundations to expand and deepen the CNPP model by significantly increasing the level of foundation support for community development. Support grew to $7 Million in 1991-93 and has continued in three-year cycles to the present day. The proposal outlined a basic structure and proposed outcomes. There was consensus on goals, priorities, governance, budget and staffing. Initial outcomes would determine future direction and support as the partnership evolved and results warranted further investment.

NPI’s version of the public-private partnership not only included the big three—business, city and foundations—but also gave neighborhood organizations seats on the Board. Board membership was restricted to senior leadership who set goals and policy rather than staff, who were expected to implement. Demands on the Board increased over time as NPI became more complex and business demands on corporate leadership increased.

In addition to the shared agenda of improving neighborhood conditions, each of the partners also benefited in its own way from this intermediary structure. The foundations were better able to leverage their resources for greater impact and align with best practices nationally; corporations got social peace and support for a downtown redevelopment agenda; City government got a non-profit community development infrastructure. All three had the added benefit of an intermediary to take the heat for unpopular decisions that were inherent in a scarcity environment. Finally, the CDCs got more funding for projects, operating and planning support for local capacity, and a seat at the table.

Operating Assumptions and Governance

Cleveland was one of several US cities (Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Indianapolis, Portland, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Memphis, El Paso and New Orleans) that created a local foundation intermediary. These cities were part of the Ford Foundation Community Development Partnership Network, which shared best practices and common problems. NPI also developed a working partnership with the two national intermediaries, Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and Enterprise Foundation (Now Enterprise Community Partners) to further leverage resources and ensure that there was an integrated strategy.

While there was no single strategic plan developed through a citywide process with metrics and outcomes, there were several shared operating assumptions among the funding partners about how NPI would go about its business.

Based on success of the CNPP model, stakeholder agreed that a local intermediary was the best way to develop a common agenda, engage business leadership, and leverage resources.

The goal was collaborating with national players to develop a shared agenda and efficient use of resources and expertise. To ensure that LISC and Enterprise continued to do business in Cleveland, NPI provided operating support for their local staff based on a shared strategic framework and understanding regarding priority projects. An agreement to coordinate operations with LISC was finalized in 1995. Both LISC and Enterprise channeled national funding to NPI programs, projects and grantees through the National Community Development Initiative (NCDI), as well as providing financing for projects. Informally, the parties agreed that the national intermediaries, not NPI, were better suited to secure corporate investment via the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit. (A vehicle for corporate investment in low-income housing projects). To have both LISC and Enterprise operating in the same city with a local intermediary was not common practice nationally. This meant that Cleveland could access national resources and expertise while maintaining local governance and a shared neighborhood strategy that addressed Cleveland’s priorities.

The partners quickly reached agreement on how it would conduct its business. Racial balance in grant-making, staffing, and board leadership was assumed. Equity, transparency and performance would guide CDC grant-making. In a resource-scarce environment, focusing on assets and targeting would be encouraged. Professionalizing CDC operations—staff, board leadership and financial accountability—and building the operating framework to support CDCs and their development agenda were initial priorities. It was believed that outcome would be greater productivity (bricks and sticks), stronger organizations, and a functioning funding partnership. This combined with school district reform and improved public services would lay the foundation for neighborhood renewal.

NPI focused exclusively on Cleveland neighborhoods, leaving regional issues to others. Likewise, NPI did not include Downtown and University Circle, where the business community, the hospitals and university had their own agendas that were not primarily neighborhood focused. The issue of anchor institutions in a place-based strategy will be discussed further in the assessment and future directions sections. (See chapter 7 and chapter 8). Also missing was any discussion of how this strategy would address the fact that Cleveland was a very poor city and that increased private investment in real estate ventures was alone unlikely to remedy the situation. A parallel organization, Poverty Commission, with a focus on social services and the culture of poverty was formed as a civic/foundation response to address the issue but it had no direct connection to NPI and its future activity.

So NPI was to stay out of politics, and policy was for others. Unlike the Ford Foundation’s earlier efforts to shape policy nationally, NPI was not expected to beta-test solutions that the public sector could scale with greater resources. If that occurred, it was a side benefit, not the focus. As the name Neighborhood Progress, Inc. implied, progress was to be achieved by adopting a more businesslike approach to community development, a modest goal. Over time NPI evolved from a funding intermediary to a more pro-active venture model with mixed results.

Structure and Program

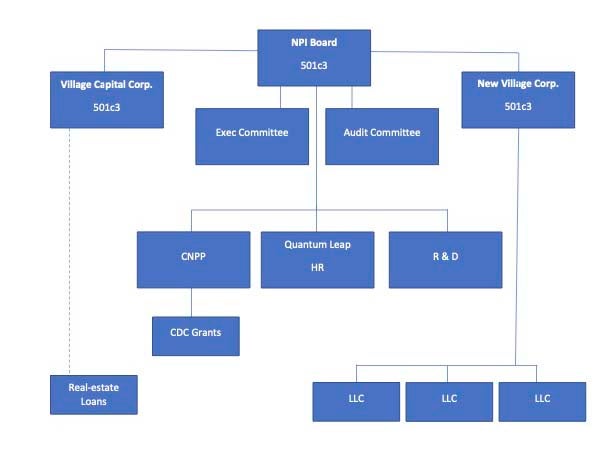

The bylaws called for audit, project finance, and CDC grant committees. Each committee was chaired by a board member and drafted outside expertise as needed. The operating grant committee consisting of foundation and city staff made CDC funding recommendations to the board; neighborhood reps did not review proposals. The real estate loan committee included loan officers from participating banks. Over time, the project finance committee became a separate 501c3 subsidiary of NPI known as the Village Capital Corporation; New Village Corporation, a real estate development subsidiary, was created later to execute joint ventures with funded CDCs. A capacity-building program for staff and organizational development called Quantum Leap was added to the mix. NPI evolved from a funding intermediary managing a CDC grant program to an operating intermediary working in partnership with CDCs to realize their development agendas.

The NPI Board

NPI was conceived as a public-private partnership representing community stakeholders each with different interests that came together to advance a shared agenda. At its core was a multiple-foundation intermediary, a conduit and manager of foundation funding for community development. It was also an affiliate program of Cleveland Tomorrow, with CEO membership. City government had board reps, and while the City did not fund NPI directly, it did fund CDCs and their projects. Also, CDCs through their trade association (Cleveland Neighborhood Development Coalition) finally had a voice in policy and priorities. CNDC was an independent organization not affiliated with NPI which allowed it to develop its own agenda and priorities based on neighborhood concerns.

The formal structure at NPI continued to evolve, and chances that it would endure for the long term, given the three-year foundation funding commitment, were uncertain. As one CEO told me, “We didn’t think you’d last more than a couple of years,” or in the words of Mort Mandel, “NPI exceeded our original expectations.”

NPI’s board was initially structured to represent the four classes of community stakeholders. Four corporate CEOs were appointed by Cleveland Tomorrow, with James Ross, CEO of BP America, selected as board chair. (Appointing a corporate CEO as board chair continued through several funding cycles.) CEO members were expected to be directly involved and not delegate their Board responsibilities to staff. The Gund and Cleveland foundations appointed board members from their respective distribution committees, not staff. The operating assumption was that Foundation lay leadership should be directly engaged as NPI Board members and represent NPI to Foundation trustees rather than Foundation staff who were not expected to play a policy role. This understanding slowly reverted to the more traditional relationship as programs and complexity grew.

Six neighborhood board members were chosen by the neighborhood advocacy coalition and Cleveland Neighborhood Development Coalition, the CDCs’ trade association. The City of Cleveland’s chief of staff and the president of city council were also represented. This was a high-powered, diverse board designed for collaboration.

That it was able to work around a shared agenda speaks well of the individual board members and was integral to NPl’s initial success. A small example of the effort to create a shared leadership culture was setting Board meetings to accommodate work schedules of members. James Ross at BP could be in London, Alaska, South Africa, or Cleveland on any given week, while Inez Killingsworth, a neighborhood rep and a School District employee, worked in food services on the day shift, so late afternoon meetings were the norm.

NPI reinforced its neighborhood connections by locating its office in neighborhood projects, including the Gordon Square Arcade in Detroit Shoreway, followed by the Glenville Enterprise Center, Ohio City’s Market District, and finally St. Lukes in Buckeye Shaker. That helped the project’s bottom line and ensured that corporate board members got a feel for the neighborhoods they were supporting.

The Board set policy, budget, overall direction, and program, as well as providing staff oversight. It was not expected to micromanage. The Board business acted on recommendations and motions from various committees and subsidiaries where members were likely to get into the detail of the programs and projects. If a Board member felt strongly about an issue, they would try to find consensus or let the issue go, if it wasn’t vital to them. Board meetings were collegial affairs. We did not discuss how corporate members and foundations were fulfilling their commitment to neighborhood renewal or ways to improve their own performance. Cleveland capital budget requests to the State and CRA reviews were never a Board topic.

Financial controls were paramount to our credibility since we were a complex organization, pushing the margins; the prospect of going off the rails was always present. The committee for annual audits included members from each of the membership classes chaired by a Board member with deep financial skills and non-profit law expertise, like John Shields, former CEO of Finast, Hossein Sadid, CFO of Case Western Reserve University, and Paul Feinberg, partner with Baker Hostetler and counsel to the Gund Foundation. Barb Hoffstetter as our CFO kept multiple financial obligations and controls in working order.

Over time, the organization became increasingly complex and technical, with greater demands on Board oversight and strategic direction. The Board evolved from one that met quarterly to review foundation proposals and evaluate performance to a complex operation with multiple subsidiaries, partnerships and committees chaired by NPI Board members.

In communicating to the larger community, NPI’s role in helping advise and advocate for CDCs and their projects was a challenge.

As an intermediary, NPI operated on a three-year funding cycle and never transitioned to an “evergreen” grantee relationship. Our proposals to core funders were reviewed and approved by the NPI Board, but it was understood that whatever the Board approved would then be subject to Foundation review and approval, and, if needed, our goals and outcomes might need to be amended. This seldom happened.

NPI Staff and Operations

Tom Cox was hired as NPI’s first president in 1989 after a national search. The foundations believed that it was important to recruit someone from the CDC world for credibility, someone from the outside who brought a fresh perspective—without the local baggage. Cox fit the bill. Prior to NPI, he was director for nine years of one of the premier CDCs in Pittsburgh. A Yale graduate and Episcopalian priest, Cox saw himself as a change agent who believed that private investment was key to neighborhood recovery. “I didn’t come here to rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic,” says Tom.

He would be the only outsider selected to manage the community development agenda in Cleveland. In 1993, he left to be deputy mayor of Pittsburgh, a position he held for 12 years. During his time at NPI, he kept corporate leadership and the foundations at the table, brought a sense of urgency and commitment to housing market recovery and the CDC strategy, and in the process laid the groundwork for much of what was to follow.

In the beginning, NPI had three professional staff who managed multiple activities (Kim Kimlin, Daryl Rush and me) along with an office manager (Rae Shea) who in the beginning and for 25 years thereafter kept the organization on an even keel. Eventually NPI would grow to a staff of 15 +/- but we maintained a program/operating overhead ratio of 94 percent and kept providing operating support for CDC our first priority. See Appendix for detail about key staff and Board members.

When Cox left NPI to become deputy mayor of Pittsburgh, I was selected as acting president, and after an extended search was hired to build on what was working and keep the neighborhood/CDC focus rather than chart a new direction. So, what was that foundation, and what was built?

Strategic Issues

Cox had summarized NPI’s strategy at the first board meeting as follows: “To create an internally generated development process in neighborhoods where the private market is not functioning properly by supporting and empowering decentralized neighborhood-based operations. CDCs.” NPI’s mission statement elaborated on this: ” To strategically invest in community development corporations and their development agenda in order to increase economic opportunity, build local capacity, create private investment opportunities and advance stakeholder objectives.”

Buried within this “banker speak” was the assumption that in a no growth region, a market/investment approach when combined with better city services, safety and quality schools would improve the quality of life for existing residents and attract those who wanted to live in a city.

In a no growth region, for Cleveland neighborhoods to prosper, they needed to compete with the suburbs for middle income homeowners and quality retail services. They needed to become, or remain, neighborhoods of choice that were desirable places to live and raise a family- not a last resort for those who had few choices.

Investing in CDCs and their agenda was viewed as a critical element in linking private investment and capacity with public and philanthropic resources. In practice, this meant a focus on assets and an expectation that CDCs would manage tensions that arise from serving the needs of low-income residents while seeking to attract and retain those with greater choices. In a no-growth region defined by suburban sprawl, this was—and remains—a stretch goal.

Housing values were seen as one indicator of neighborhood health and competitiveness, not the end goal. The operating premise for NPI was that the CDC strategy was the best way to ease the tension between improving quality of life for existing residents with few choices and providing the amenities necessary to attract and retain a more affluent middle class. In this environment, the issue was how to deploy scarce grant resources and staff for maximum impact.

The human resource issue was essential to our approach because without effective neighborhood-based organization with excellent staff and Board members who were able to translate community needs into a realistic agenda, the big picture goals would be nothing but rhetoric that raised expectations that were not met.

NPI was not a social service operation, our focus during this period was on transactions, with a premium placed on execution. Both market-rate and low-income housing were pursued as resources came available. Investment decisions were based in part on neighborhood priorities that emerged from the planning process of the funded CDCs.

NPI’s neighborhood revitalization strategy was built on CDCs and support for project managers. In the beginning, the real estate development focus was on single-family rehab, home repair, weatherization programs, and retail merchant support, in line with local capacity. Of the fifteen CDCs initially receiving operating support from NPI, there was a wide range of development capacity, often related to staff quality and market opportunities. Training programs, development coaches, and various forms of technical assistance were viewed as necessary adjuncts to operating grant support for project managers. Over time, because projects became more complex and markets crossed ward boundaries, the ability of CDCs citywide to support development staff financially and deploy them effectively became more of an issue. This led to an increased role for New Village Corporation in some instances and, more significantly, the Cleveland Housing Network.

Tactics

Within its core mission—supporting CDCs—NPI could respond to changes in local conditions, changing environment and economy. This required flexible tactics and strategies. While never explicitly stated, these approaches guided operations and strategy.

NPI “Fortune Cookies”

- Focus on neighborhood Assets not Liabilities.

- Listen to the community

- Markets matter.

- Break Down Silos.

- Right size the problem/solution to ensure successful outcome.

- Target scarce resources and avoid peanut butter approach.

- Beware the White Whale projects and keep focus on the big picture

- Quality lasts.

- Invest in people and their priorities

- Partnership and collaboration are key.

NPI Programs and Subsidiaries

To advance its strategy for neighborhood reinvestment, NPI developed a set of programs to support CDCs and leverage public, private and philanthropic resources these included: a performance based operating support program (CNPP), a human resource and organizational development program (Quantum Leap), a real estate finance subsidiary (Village Capital), a real estate development subsidiary (New Village Corporation), and an applied research and development capacity.

Cleveland Neighborhood Partnership Program

Providing multiyear operating support to CDCs citywide was the core NPI program (CNPP). Based on a competitive request for proposals, NPI supported, on average, 18 CDCs in a city with 33 council wards and 35 neighborhood planning areas. Annual grants of $125,000 to $175,000 were awarded to the more established CDCs. For emerging ones, the range was $65,000 to $100,000. In addition to project financing support, NPI provided technical assistance and training resources. A committee of local funders made decisions on grantees following staff write-ups and recommendations. Total operating grant support to CDCs over three years was approximately $7Million.

The CNPP proposal format called for identifying neighborhood strategies, projects and likely impact. Neighborhood support for priorities was required, as were timeline and deliverables. Use of funds was detailed, and an annual audit was expected. NPI prioritized targeting resources for impact, and preference in funding tended to favor project managers. In addition to NPI support, most funded CDCs received federal Community Development Block Grant money from the city, council ward allocations, project fees, and local fund-raising.

Expectations were that grantees would be better managed, remain connected to the community, produce new and rehabilitated housing units, visibly improve the neighborhood, stabilize retail corridors, and address safety and blight. A memorandum of understanding defined the terms of the grant commitment and expected outcomes, as well as what NPI was expected to provide grantees to realize their objectives. These agreements informed NPI’s request for foundation support–goals achieved and future direction. The CDCs’ success determined NPI’s funding level and required that we work together for a common outcome.

A key element of NPI’S operating grant commitment to CDCs required a selected target area for redevelopment that described development/project goals. Planning grants were given, and training was offered. Starting with a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) stakeholders began to craft a plan for the neighborhood. One of the key real estate training elements was producing a two-page go/no-go decision paper to clarify what a successful development would require. Funded CDCs received support to hire a project manager and access to Village Capital predevelopment funding. A memorandum of understanding between the CDC and NPI outlined a timeline for deliverables and identified the resources needed. Over time, this was refined as the Strategic Investment Initiative, which took targeting and comprehensive redevelopment to another level with mixed results, given resource, market and ward-based challenges.

CNPP Support

According to Bill Whitney, former ED Detroit Shoreway Community Development Corporation, “Doing a real estate development project generally takes longer than a year. And if you’re going to do it right—by building a neighborhood rational planning process—it can take even longer. When you must keep hiring new project managers, there’s a learning curve, almost like starting all over. The great thing about being able to count on ongoing multiyear support from CNPP has been the stability it has given us. Relationships are built, as well as a development team that knows the big picture and is used to working together.”

CDC Grantees: The following CDCs received multi-year operating support grant through CNPP:

Amistad Development, Bellaire Puritas Development Corporation, Burten Bell Carr Development Inc., Buckeye Area Development Corporation, Clark Metro, Cudell Improvement, Detroit Shoreway Community Development Corporation, Famicos Foundation , Fairfax Renaissance Development Corporation, Hough Area Partners in Progress, Ohio City Near West Development Corporation, Northeast Shores Development Corporation, Mt. Pleasant NOW, Stockyards Area Development, Shaker Square Area Development Corporation, St. Clair Superior Development Corporation, Tremont West Development Corporation, Union Miles Development Corporation

Capacity Building (Quantum Leap)

The evolution of community development corporations from volunteer neighborhood advocacy organizations to a system with professional staff, board leadership, financial controls, real estate development and planning skills in multiple neighborhoods was a significant achievement. As stand-alone 501c3 nonprofits, rather than the development arms of established social service organizations, CDCs had to be built from the ground up. There were trade-offs to this approach which will be discussed later.

In short order, Cleveland went from a few community development corporations to 30 501c3 organizations employing approximately 200 employees in total, some more than others. Each CDC had a community board of directors. The capacity and neighborhood base of these organizations varied. From 1988 to 1991 the median operating budgets of existing CDCs increased from $325,000 to over $500,000 and the level of real estate production grew significantly.

Initially, intensive training for a limited number of executive directors was provided by the Development Training Institute and through a certificate program in economic development offered by the National Development Council. In addition, the Center for Neighborhood Development at Cleveland State University provided training and coaching for staff and board members. NPI also worked with ShoreBank Advisory Services and Charlie Rial to develop a real estate training program, one outcome being the one page “go-no go project feasibility paper that helped clarify the difference between a problem and a project. Building on these efforts, NPI realized that creating a high-quality, sustainable community development system demanded a targeted investment strategy to address human resource and organizational needs.

To address this situation, NPI formed a human resource advisory committee chaired by retired Finast CEO Richard Boglomony which contracted with the Development Training Institute to survey 27 executive directors of community-based development organizations (CBDOs), senior development staff and board chairs. The findings were summarized in a report, “Investing in People…A Human Resource Plan for Investing in Cleveland’s Neighborhood Development Industry” that addressed workforce and community characteristics, recruitment and retention, compensation/salary and benefits, training and education, career development and personnel practices. Grants from the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations initially supported this work.

Based on this survey and recommendations from its Human Resource Advisory Committee, NPI then conducted a national search for a senior human resource professional to implement the capacity building plan. We hired Daryl Burrows from Bethel New Life in Chicago. Burrows, a Harvard grad with over 20 years’ experience in human resource training and organizational development, made a “Quantum Leap” in our capacity building efforts. To support the next level of system building we submitted, along with the local LISC and Enterprise offices, a multi-year grant request of $375,000 to the Human Capital Development Initiative (HCDI), a consortium of national foundations. The request was approved.

Of the 30 Cleveland CDCs, 21 participated in Quantum Leap, including those that received operating support grants from NPI. Quantum Leap provided a mix of training, staff and board development, consultants, coaches, search firms and peer support. The goal was to build stronger CDCs with the capacity to make a difference in their neighborhoods. It was based on the CDC’s assessment of its own organizational needs and mutually agreed upon operating guidelines. Capacity building was seen as professionalizing operations while maintaining core community values.

Quantum Leap functioned, in effect, as the human resources department of the local CDC industry. Working with the Center for Neighborhood Development at Cleveland State University and the Mandel Center for Nonprofit Organizations at Case Western Reserve University, Quantum Leap helped create an organizational template and human capital agenda for the emerging CDC field in Cleveland.

Real Estate Finance and Development—A Synergistic Approach

Village Capital (Development Finance)

In 1993, NPI created Village Capital Corporation (VCC) as a wholly owned 501a 3 subsidiary designed to serve as NPI’s real estate finance vehicle. VCC provides flexible investment funds in the form of loans and grants to community-generated real estate projects in Cleveland’s distressed neighborhoods.

Initial funding came in the form of program-related investment loans (PRI) and grants from BP America, The Ford Foundation, The Cleveland Foundation, Cleveland Tomorrow, the George Gund Foundation, the National Community Development Initiative, and the Premier Industrial Foundation. PRI loans allowed foundations to provide below-market-rate financing with favorable terms to VCC for nonprofit-sponsored projects while enabling private foundation funders to meet minimum distribution requirements. VCC subsequently was awarded two equity investments from the Community Development Finance Institutions Program of the US Treasury totaling $2.8 million. These helped secure program-related investments from foundations, and bank lines of credit. Later the Cleveland Foundation converted its $10 million PRI loan to an equity grant. Over time, VCC had upward of $20 million in loan capital under management.

VCC was governed by a 13-member board of trustees comprised of representatives from the investment community, the city administration, real estate, law, finance and development. Board members were incredibly important in that they were senior management who gained an understanding of why the project mattered, how it would fit into their own institution’s loan underwriting, as well as providing guidance to staff who would be responsible for structuring the banks’ participation. Within this framework evolved an understanding about how risk should be apportioned. The chair of the VCC board was also an NPI board member, and in several instances the chair of VCC would later become NPI chair. Bud Koch (Charter One) and David Goldberg (Ohio Savings) were two notable chairs. Talented finance professionals Kim Kimlin, Deb Janik and Linda Warren, developed policies and procedures, packaged loans and helped provide strategic direction for the board. Despite a thin support staff and a charitable-purpose mandate, VCC was able to provide critical funding for a range of projects that advanced NPl’s overall agenda with minimal losses. The loan portfolio was reviewed annually by an outside auditor, and loan-loss reserves were allocated accordingly. Net asset ratios, pricing fees, and credit quality were adjusted for market conditions and industry standards. VCC’s general underwriting policies required that: 1) the projects be catalytic and make economic sense in the long run; 2) the local community development corporation be a partner/sponsor; 3) the projects be carried out by an appropriate development team; 4) the transactions leveraged other private/public investment; 5) projects must be located in CDBG-designated areas within the city of Cleveland.

In a weak market environment where there is a value gap between the cost of creating a quality project and its appraised value, structuring a deal that makes economic sense for the developer, the private lender/investor, and the public sector required VCC to provide flexible financing products. Of particular importance early on was predevelopment financing in the form of recoverable grants that enabled the CDC to assess feasibility, identify environmental issues, and obtain site control options. Once the project moved beyond feasibility, VCC would provide acquisition and construction loans and was instrumental in bringing other lenders to the table and providing gap funding as needed. VCC grant and loan products included: feasibility, pre-development and project grants: bridge, acquisition, construction, mini-perm, and linked deposits. In addition to funding CDC projects directly, VCC would also manage and structure PRI loans on behalf of local foundations for larger neighborhood catalytic projects done by private developers, such as Beacon Place Shopping Center in Fairfax.

“VCC often takes the front-end risk by providing the gap financing that enables a CDC to go forward with a project which it might have trouble interesting a commercial bank (in) at that stage. A combination of recoverable grants and flexible loans makes many neighborhoods’ deals possible.” —Deb Janik, former Village Capital VP for Community Finance

New Village Corporation (NVC)

New Village Corporation was formed in 1990 as a real estate development affiliate of NPI in response to an RFP from the Department of Housing and Urban Development for developing affordable home-ownership projects for low-income residents. NVC using the Nehemiah grant program leveraged city grants and bank financing for two such projects in the Glenville and Central neighborhoods. Both were done in partnership with the local CDC. There was no long-term plan for NVC, only the opportunity to bring needed resources to Cleveland to address a perceived need it evolved in support of NPl’s core mission of fortifying CDCs through partnerships, developing catalytic projects in communities of need.

It focused on large, complex neighborhood development projects for which the private sector had little appetite and the CDC often lacked the resources and expertise to undertake on its own. In these projects, NVC entered a joint venture limited liability partnership with the CDC in which key management decisions and development fees were equally divided. In addition, the CDC took the lead in neighborhood planning, community engagement, and supporting activities like merchant associations and housing rehab. The projects were often “hero deals”—large commercial projects or mixed-use shopping centers, neighborhood supermarkets, or market-rate housing of scale, and they could be both new construction and adaptive reuse. Village Capital played a critical role in providing early financing to all the projects undertaken by NVC.

Of particular importance in developing a retail strategy was partnership with Cleveland’s Saltzman family. This led to development of four Dave’s Supermarkets in underserved neighborhoods, providing jobs and groceries, often as part of a larger placemaking investment plan (See PlaceMaking Deals for further detail.)

NVC’s largest retail project was purchase and renovation of the 220,000-square-foot Lee-Harvard Shopping Center in a joint venture with Amistad Development Corporation, the local CDC, and Forest City Enterprises. NVC used a $500,000 loan from VCC to acquire the shopping center. The $22-million project created and retained 810 jobs and a range of quality retail tenants, including a supermarket and 20,000 square feet of medical office space for the neighborhood.

The most complex project undertaken was the $65MM mixed-use, multi-phase redevelopment of the historic St. Lukes hospital campus. (See Placemaking for further detail.)

NVC was governed by a small Board of experienced real estate development professionals chaired by Robert Kaye, who at the time was CEO of Metropolitan Savings as well as a major real estate development company in New Jersey. NVC operated with minimum capital and staff. Russell Berusch, who would become vice president for commercial development at Case Western Reserve University, was NVC’s first real estate VP. Staff consisted of a project manager, NPl’s accountant/CFO and other NPI/VCC employees as needed, including the CEO who filled in during staff transitions. Although NVC was a subsidiary of NPI, with the exception of the St. Lukes redevelopment, NPI never co-signed on a project, though NVC’s balance sheet was reflected in NPI year-end financial statements. NVC only did deals with CDC partners in neighborhood transition areas with undervalued assets and unrealized market potential.

During this period, no NVC project failed. While NPI provided support for core staff, NVC covered its operating costs from project revenue and was never a financial drain on NPl’s core operations. NVC successfully completed 12 projects valued at over $150 million, often working in tandem with Village Capital, which provided risk capital and early-stage financing.

R&D Initiatives

NPI had a broad mandate and staff able to multitask. Over the period discussed, several studies and exploratory initiatives were undertaken to address neighborhood issues and related resource needs. While intended to support CDCs, NPI staff was often the primary driver, while the board provided budget and program oversight to some of the higher-risk projects. R&D was not seen as a core NPI function, and its potential was never fully realized, but a look at the activities undertaken suggests that applied R&D could play a significant role in shaping strategy for a community development system. Whether this was a role for NPI, either to keep in house or spin off to another entity, and if so, how best to make this a core NPI funded function was never resolved. The list of R&D efforts is still impressive, however.

- The Neighborhood Economy Initiative and ShoreBank: Bringing private market resources and expertise were priorities for the foundations and corporate community. ShoreBank was a community lending institution with extensive experience in providing credit to distressed municipalities in Arkansas and Chicago. NPI helped bring ShoreBank to Cleveland by acquiring and stabilizing an abandoned factory facility (the Pullman torpedo plant) on the east side to serve as a business incubator for minority enterprise. NPI was a tenant of the Glenville Enterprise Center, and an advocate for the $5 million in seed capital for ShoreBank from Cleveland Tomorrow and the Cleveland Foundation.

- Building a Sustainable Housing Production System for Cleveland’s Neighborhoods: This study by the firm Hamilton and Rabinowitz was commissioned by NPI, LISC and Enterprise in 1997 to assess the real estate finance system and recommend ways to increase housing production in the city to 500 for-sale units and 1,000 home-improvement loans annually. This represented a 57-percent increase from existing output levels, and if sustained over a five-year period was projected to stabilize the Cleveland housing market.

To realize this increased volume, $49 million in additional nonmarket funding was proposed in the form of subordinate debt, nonrecoverable grants, funds for home repair financing, land assembly and infrastructure. Bonds, tax-increment financing and new forms of creative financing were recommended.

In addition to financial products, the report recommended a more targeted and comprehensive approach, expanding the pool of builder/developers and citywide capacity to assemble land, structure financial transactions, and manage a large and growing portfolio of rental property. While never fully implemented, the study provided a template for the types of financial capacity needed and the resources necessary for Cleveland to “go to scale.” Home Repair – The Fix-It Fund: This fund targeted non-historic district neighborhoods for emergency repair and exterior upgrades. It was our attempt to deal with a preservation agenda in middle market neighborhoods targeted by funded CDCs where abandonment and vacant property was not the defining issue. In the pilot stage, the Fix -It Fund originated 210 loans, and later a key element in our Model Block initiative. NPI followed with a proposal to the administration of then-Mayor Jane Campbell’s administration for underwriting a home repair bond fund based on the Fix-It Fund model. The Administration rejected it for fear it would negatively affect the city’s bond rating.

- Vacant Property and Land Assembly: As foreclosure and abandonment began to increase in several at-risk neighborhoods acquiring vacant property went beyond the capacity of most CDCs or the city’s landbank and required a more proactive approach. In response, NPI commissioned a study by Smart Growth America in 2003 to analyze the situation and recommend a response. Cleveland at the Crossroads: Turning Abandonment into Opportunity, the study by Allan Mallach and Joe Schilling in 2005 was one of the first of its kind nationally undertaken by Smart Growth America. It addressed the issue of vacant and abandoned property and made a series of policy recommendations that supported forming the Vacant and Abandoned Property Action Council (VAPAC) a county-wide multi-agency coalition, a property data system at Case Western Reserve University. (NEO CANDO), and code enforcement policies for Housing Court. (See Mortgage Foreclosure section for further info.)

- Reimagining A More Sustainable Cleveland and the Cleveland Pattern Book: A joint initiative of NPI and Kent State University Design Center led by Bobbi Reichtel and Dr. Terri Schwartz, produced a report and series recommendations for green space reclamation to address right-sizing Cleveland in a period of population decline and growing vacant land inventory. The recommendations were adopted by the City Planning Department. A “how to” pattern book for green re-development for neighborhood practitioners was also produced. (See Cleveland Response to Sub Prime Mortgage Collapse for further detail.)

- Cleveland Neighborhood Main Street Initiative: A two-year pilot working with LISC, the Cleveland Neighborhood Development Corporation and four CDCs, this integrated real estate development with marketing and merchant organizing.

- Brownfields Redevelopment Initiative: A Brownfields Resource Information Guide, prepared by Paul Christensen a former McKinsey associate and NPI staffer worked with the Cuyahoga Planning Commission to provide technical assistance and support for projects requiring environmental assessment and remediation. The initiative helped the City of Cleveland in applying for a blanket Urban Setting Designation to expedite cleanup of 9,000 acres of vacant or abandoned industrial land. Legislative recommendations to the city for assessing groundwater contamination on brownfield sites were also drafted.

- Land Assembly: NPI assembled a working group with Kermit Lind of the Cleveland State Law School to help CDCs acquire privately owned property in areas targeted by the Strategic Investment Initiative. The land Assembly Team lead to the formation of neighborhood Stabilization Team the precursor of the county side Vacant Property Council. In addition, New Village Corporation formed a subsidiary LAND LTD (Land Assembly for Neighborhood Development) to hold privately acquired property north of Chester Avenue adjacent to the Cleveland Clinic and a target area north of Case Western Reserve University. We partnered with two private developers and a local CDC (Famicos Foundation) to build market-rate homes on 50 vacant lots for employees of University Circle institutions. We had hoped to develop a model like the University of Pennsylvania’s neighborhood/employee program in West Philadelphia, but we were not successful. While we never did build the 50 market rate homes for sale, Finch did build Innova (a multi-family mixed use development) and CHN built Heritage Homes (a senior LIHTC apartment building).

- Other: Staff-driven efforts to address different aspects of neighborhood redevelopment included a) a study of Cleveland’s retail market done with private developer Forest City that mapped neighborhood supermarket potential in underserved areas (food deserts) and helped inform work with the Saltzman family’s siting of new facilities; b) a feasibility study for a preliminary proposal to Cuyahoga County by Starting Point for developing new child-care; c) various marketing efforts to promote neighborhoods.

Note: For a comprehensive overview of NPI related material see: Neighborhood Progress Research Collection compiled by Bob Jaquay of the Gund Foundation.