Main Body

Chapter 5 Neighborhood Planning and Placemaking

Placemaking

Placemaking as currently defined focuses on equitable regional development strategies to rebuild market strength and increase economic diversity in disinvested neighborhoods. The goal is to improve conditions for residents in disinvested communities by improving physical conditions and community fabric as opposed to a voucher approach that attempts to move families to a better place with more resources and opportunities. Ideally both people and place strategies should complement one another but the history of racial segregation shows this to be a difficult marriage.

NPI’s neighborhood redevelopment strategy, as I stated previously, was built on targeting resources to leverage market opportunities and create regionally competitive places that could attract and retain residents who had choices as to where to live and invest. The assumption was that these anchor projects would be of sufficient scale when linked with CDC block clubs, home repair programming, greenspace, and retail services to create desirable communities for new and existing residents. Linking these investments to major regional employers—eds, meds and corporate headquarter priorities—was an aspirational goal seldom realized.

The following projects illustrate how placemaking helped define Cleveland’s redevelopment strategy. They are not the sum of impact deals done, but each has a story and offers some insight into the community dynamics that shaped the outcome.

The ten (10) examples of neighborhood placemaking selected share a number of common features while their outcomes varied. All of the projects described warrant further treatment as detailed case studies that would inform the work of emerging community development practitioners interested in how real estate deals get done. What follows is the overview.

All of the projects described involved a CDC supported by NPI that kept the community agenda in the forefront and things moving forward as obstacles were encountered and resolved. The projects were of scale, supported by the community, and involved a range of complementary activity that leveraged the investment. All involved a working public private partnership between city, the foundations and NPI, and local banks to address cost and market factors. A handful of private developer partners and NVC provided the technical capacity and risk capital in a limited liability company with the CDC. Land assembly was key since eminent domain was never politically viable. The projects were a mix of planned unit developments, scatter site in fill, middle income home ownership, tax credit and historic rehab. Retail, arts and entertainment provided needed services and community identity in a number of cases. All of the projects described involved creative problem solving and evolved from a single project to a more comprehensive agenda with greater impact. The history of the Gordon Square Arts District is a case in point.

Gordon Square Arts District

Thirty-five years ago, before my stint at NPI, I was project manager for Detroit Shoreway Community Development Corporation (DSCDO). The Gordon Square Arcade, a 1920s shopping center and anchor of Detroit-Shoreway’s commercial district, was on the verge of collapse. Parts of the crumbling brick façade on W 65th Street fell on cars parked below. A single-room-occupancy hotel on the building’s second floor was no longer viable, stores along Detroit Avenue were vacant, and the Capitol Theatre had not shown a movie in years. There was strong sentiment for demolition.

DSCDO, Father Marino Frascatti, pastor of the neighboring Our Lady of Mount Carmel, parish church for the Italian American neighborhood, and then-Councilman Ray Pianka were determined to save this landmark, critical to the long-term health of its community. Rental housing for elderly parishioners and shopping for residents were needed, and a large vacant lot at 65th and Detroit would have been disastrous.

A joint venture was put together by DSCDO and developer John Ferchill, who had ties to the pastor. The project was one of the first tax-credit efforts in a Cleveland neighborhood, with investment from Standard Oil and Enterprise Social Investment Corporation. The plan was to subdivide the arcade with air rights for the second floor. Low-income rental apartments there would be owned and managed by Ferchill, and ground floor retail by DSCDO.

Successful renovation of the Arcade anchored the commercial hub of the neighborhood and laid the groundwork for the $30-million development of the Gordon Square Arts District 35 years later. (See Dennis Keating). Along the way, James Levin provided a permanent home for Cleveland Public Theatre at 65th and Detroit, and a new arts district organization representing stakeholders was formed to raise funds and manage the district. With development of upscale residential properties like the Tillman Townhomes and Battery Park, along with several low-income multi-family units and a redo of the Shoreway that connected the neighborhood to the lake, Detroit Shoreway has emerged as one of Cleveland’s premier neighborhoods.

The Detroit Shoreway Community Development Corporation was able to meld together an old-time, Italian ethnic community with gay lifestyle professionals, urban homesteaders, and the arts and entertainment crowd. NPI supported DSCDO’s work during this period with operating grants and various levels of project financing through Village Capital; DSCDO called the shots, and NPI responded.

The lesson I draw from this is that transformative redevelopment often takes time—a generation—stakeholder commitments, multiple partnerships, political leadership, a defining vision, market savvy, and resources to match. Piece of cake.

North Park Place and the Glenville Enterprise Center

NPI moved its offices from the Gordon Square Arcade in 1991 to the Glenville neighborhood to develop the 49-unit North Park Place housing subdivision and to renovate an abandoned 135,000-square-foot factory building as the Glenville Enterprise Center business incubator. The Enterprise Center would be owned and managed by Chicago-based ShoreBank as part of what was called by NPI the Neighborhood Economy Initiative. This two- pronged strategy was one of the first attempts to combine a housing project of scale with support for neighborhood business development. It was partially successful.

The housing development originated as a successful application by New Village Corporation (a newly formed real estate subdivision of NPI) to HUD for a project grant from the Nehemiah housing program. The project was to develop forty-nine new homes for first-time low and moderate-income buyers. We partnered with Glenville Development Corporation, the local CDC, to do the project.

North Park Place was one of the first new housing developments supported by Mayor Mike White’s administration with roads, infrastructure, second-mortgage financing, and tax abatement. The 1,600-square-foot single-family homes with two-car garages were designed by the local firm Whitley and Whitley. There were three models that sold for $110,000 on average, and demand was strong. The builder was Snavely Group, an experienced suburban developer with a good track record that kept the project moving forward despite site challenges.

Financing for the project, in addition to the Nehemiah homeowner grant, included a VCC acquisition loan, and the city paid for new streets and utilities, buyer second mortgage financing, and ten-year tax abatement. National City Bank financed the model home and provided first-mortgage buyer loans. For first-time home buyers, which was a very attractive package.

With most inner-city development, soil conditions and environmental issues surfaced (no pun intended), creating complications, delays and unanticipated costs. North Park is a case in point. We discovered that our building site (the factory parking lot) was paved over the Doan Brook meander, which was filled with debris. This required a new site plan, removal of the debris, and trucking in clean fill that was dynamically compacted (dropping a 20-foot cylinder from a great height damaging crockery two blocks away). The city covered the extra cost, and the subdivision was completed on schedule. Today, the houses are well-maintained, there are no vacancies, and there is a strong sense of community. Since local banks originated and held the mortgages, there was no subprime meltdown. So, while at the project level, North Park Place was a great success, it and the Glenville Enterprise Center, along with Eastside Food Market, did not transform the neighborhood. Why not?

The main reason, I believe, was that we underestimated the level of disinvestment, what it would take to re-weave the neighborhood fabric and the resources needed to sustain the effort. The factory site, the Nehemiah grant, bringing ShoreBank to Cleveland, and wanting to do something in Mayor White’s old City Council ward drove the selection process. The challenges of making the project work and getting ShoreBank up and running consumed staff energy and attention. There was no neighborhood plan for the area, which was run-down and cut off from the lake, parks and other community assets. The CDC, Glenville Development, was not particularly good at block club organizing or bringing local stakeholders to the table (unlike Detroit Shoreway). The ward had a history of indifferent council members so there was no clear political vision or leadership.

Finally, we and ShoreBank were unable to link the economic development engines (the Enterprise Center and Eastside Food Market) to one another or, more importantly, to the community and the institutions at University Circle. Thirty years later, except for North Park Place, the neighborhood is much the same, despite the best of intentions. In contrast, efforts to rebuild the Central neighborhood, described in the next section, had a more favorable outcome and demonstrate the value of political leadership, community input, good design, infrastructure and market savvy.

Central Commons Home Ownership Zone Arbor Park Shopping Center

A positive outcome of the successful Glenville Nehemiah North Park Place project was that HUD viewed NPI as a credible developer when we applied for a second grant. We proposed an 81-unit Nehemiah development in the Central neighborhood. New Village Corporation partnered with the newly formed Burten Bell Carr Development Inc., which in the beginning had one staff member and a resident board. Neighborhood Progress provided operating support. Councilman Frank Jackson, who would become Cleveland’s mayor, was clear about what he wanted: affordable homeownership for residents and folks who worked in the area and no displacement or public taking of vacant land. This meant piecing together private acquisitions with Land Bank lots to create a fifteen-acre development site for residential units costing less than $120,000.

NPI wanted to demonstrate that moderate-income housing in a high- poverty neighborhood could be done affordably to a high design standard with a site plan that was woven into the neighborhood and would be a building block for further development.

Given cost constraints, selecting the architectural firm of Duany Plater-Zyberk was a bit of a stretch. The Miami-based founder of the Congress for New Urbanism, DPZ is internationally known for the planned-unit upscale development of Seaside in the Florida Panhandle, but it had never done a low-income, inner-city project. Because of the challenges of the Central project (Central Commons), DPZ was willing to accept the engagement at a reduced fee that was covered by a special grant and not part of the project cost. The new urbanist approach emphasized walkable communities, a range of traditional housing styles, design guidelines, and shared public space. In Cleveland this meant reworking the street grid to shorten the blocks and create small housing clusters around a Close, with porches and garages in the rear off alleys. The intent was to create a safe, walkable place, with neighbors that looked out for one another: eyes, not a fenced, stand-alone subdivision.

DPZ partnered with the local landscape design firm Schmidt Copeland Parker Stevens and conducted a series of design charettes to get resident, builder and city input making sure the models would pencil out. Changes were made to stay within budget—Hardie-board became vinyl, ceiling heights were lowered, the porches shrank, there were fewer alleys, but in the end, we had a product and design that worked.

What also worked was the development partnership put together for the project. New Village and Burten Bell Carr formed an LLC with a subsidiary of National City Bank, which agreed to fund construction of a model home with the parent bank providing mortgage financing for the buyers. The LLC hired a local Realtor to staff the model and work on qualifying the first-time buyers. There was a homeownership association with a code of regulations, design guidelines and owner governance.

Despite the success of Central Commons, Cleveland did not choose to replicate the new urbanist model, nor participate in the Congress for the New Urbanism which would have linked Cleveland to an international network of urban professionals committed to new approaches to sustainable development. Nonetheless, thirty years later, half of the original buyers are still there, the houses look good, there are no vacancies, and there was little fallout from the mortgage foreclosure meltdown. Central Commons was the catalyst for further market-rate housing development in Central and contributed to the first new retail in the area in over 20 years. Key to this evolution was the growth of BBC as a strong development partner following the hiring of Tim Tramble as executive director.

Arbor Park Shopping Center and the Homeownership Zone

Arbor Park is a 39,000-square-foot retail shopping center at Community College Avenue and East 40th Street. It replaced Longwood Plaza, with its marginal shops in deteriorating buildings with sub-standard merchandise for public housing residents. Frank Jackson, at that time City Council president, had failed to attract a developer to the location. New Village Corporation formed an LLC with Burten Bell Carr CDC and began working with the councilman to acquire the plaza from the owner. three years of negotiations, the LLC acquired the site, put together 10 separate sources of financing, and recruited the Dave’s Supermarket chain as anchor. Burten Bell Carr assumed management and eventual ownership.

At this time, the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority had been awarded one of 6 HOPE VI grants nationally to redo the existing public housing estates in Central along with a major upgrade of Arbor Park, a several hundred-unit Section 8, place-based development that had gone into default. Along with Central Commons, the Nehemiah home ownership development, Central was well positioned to secure a Homeownership Zone designation and a $4.6 million grant from HUD, which, along with significant vacant land assembled through the city’s Land bank and private acquisition by BBC leading to construction and sale of more than 200 new, market-rate homes in Central.

As a result of this combined investment and the focus of new Mayor (and area resident) Frank Jackson, Central, despite its concentration of public housing, has one of the stronger private housing markets on the city’s east side and is a neighborhood many are proud to call home.

Mill Creek Subdivision

When the state of Ohio closed its 111-acre mental health facility in Slavic Village in the early nineties, the Broadway Area Housing Coalition (BAHC) stepped up to redevelop the site. Working with Councilman Earle Turner, the city, and the state housing representative, they were able to get the state to convey the property for a token sales price, demolish the buildings and do the extensive environmental cleanup and infrastructure building required for redevelopment. The city and BAHC then issued a request for proposals and selected Zaremba, a suburban builder/developer with an excellent track record.

Adjacent to the Metroparks and Mill Creek Falls, Mill Creek was developed as 250 single-family homes with a community center and gazebo on a Commons available to the larger neighborhood and linked to the Metroparks. It is a planned community with a varied streetscape and a range of single-family homes in the $160,000-$240,000 price range. The city provided roads, tax abatement, and other incentives.

Mill Creek was the first suburban-quality subdivision in the city. Of special note was BAHC’s affirmative marketing campaign designed to attract home buyers who wanted to live in a racially integrated development. It worked. There was no fallout from the subprime meltdown at Mill Creek—unlike the rest of Slavic Village—and the development has retained its value and appearance. U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown and his wife, syndicated columnist Connie Schultz, were early residents and have remained along with many of the original home owners. Mill Creek proved that home buyers who could elect a suburban location would purchase a home in the city with favorable financing, quality design and amenities. Cleveland could compete!

Mill Creek, however, had little impact on the surrounding Warner-Turney neighborhood in the sense of further development, either residential or commercial, though there was no displacement, and the immediate area remains a traditional Cleveland neighborhood in good repair. The Zaremba company continued to develop middle-income housing in the city (Beacon Place) and sent a signal to other builders that they could do business in the city.

Lexington Village, Beacon Place and the Suburban Homes of Hough

One of the first public- private housing partnerships in the late ’80s, Lexington Village was a joint venture among the Famicos Foundation (the local CDC), and McCormack Baron Salazar Company, a national affordable housing developer from St. Louis. Many view the 277-unit garden apartment rental development in Hough as the catalyst for new housing development in the city, although some mistakenly refer to it as a market-rate home ownership project. The Cleveland Foundation played a leading role in pulling the financial package together, requiring a combination of public subsidy—UDAG grants, tax abatement, cleanup funds, and infrastructure money—as well as bank financing, foundation grants, and program-related investment loans. Steve Minter took the lead in securing the $13 million needed to build the first phase of the project—with support from 27 public and private partners.

Lexington Village also served as the catalyst for the development of Church Square Commons on E. 73rd and Euclid Avenue the first new retail complex on the eastside in years financed with a mix of foundation/VCC loans, city grants and bank financing from National City bank.

Lexington Village was a low-income rental project that did not increase property values in the area or alter the view of Hough as a poverty neighborhood. What changed perceptions was the new suburban-style home built for retired Cleveland Police commander Tell on Chester Avenue and viewed by a steady stream of downtown commuters.

The Tell house was the first of over 100 owner-designed, suburban-style homes constructed on vacant lots in the Hough neighborhood.

They were comparable to new, upscale housing in the eastern suburbs. Renaissance Place, a planned intentional development of 20 homes was jointly conceived and implemented by Carolyn Allen, former Cleveland safety director, with friends and colleagues who decided that they could have what they wanted at a lower cost in a community more congenial to the African American experience.

The City, the local CDC, Hough Area Partners, and Councilwoman Fannie Lewis worked with buyers to secure land, tax abatement, and second mortgages. Individual builders constructed the homes for owners, and local banks provided construction loans and takeout mortgages, even though existing home values in Hough were well below the cost of the new homes. Currently, median sales prices in Hough are still in the bottom quartile in the city, but the designer homes are occupied, look very suburban, and are a reminder that not everyone wants to live in the ’burbs when they can get better quality at a reasonable price, make a life-style statement, and assert cultural values.

Beacon Place is a 120 + market rate, planned unit, town house, development by the Zaremba Company that was heavily supported by the White Administration. Adjoining the Church Square retail shopping center on E 79th between Chester and Euclid Avenues, its primary market was Cleveland Clinic employees and though it took a while to complete, it was/is a successful project of scale.

Ohio City Market District

The Ohio City Market area is a designated historic district near the intersection of West 25th Street and Lorain Avenue, anchored by the iconic West Side Market and home to Great Lakes Brewery. In the early ’90s, vacant buildings, marginal retail, and a high-rise public housing complex along West 25th defined the area. The notion that a vibrant district supporting a range of shopping and residential uses would take hold seemed a reach at the time.

Gaining neighborhood consensus about what was to be done began with the merger of Ohio City and Near West Housing Development Corporations as a condition for operating support from NPI. Each of the organizations represented different constituencies—the gentrifiers and the low-income housing advocates–and were often at cross purposes when it came to projects and priorities. The merged organization was able to work through the multiple issues that arose as the Market District development moved forward.

NPI had relocated its office to Ohio City in 1996 in anticipation of a protracted redevelopment agenda. We believed that three projects would move the district forward: A Dave’s Supermarket, the Merrill Building and the Fries and Schuele block.

Dave’s Supermarket

As much as the West Side Market was a regional draw, it was more a place where families shopped for the holidays and weekend parties and tourists came for the ethnic flavor. There was no quality grocery store downtown or on the near west side. There was clearly a need, but there was no suitable site and the larger grocery chains were not interested in fitting a modern store into a historic district with a diverse customer base.

A joint venture of New Village Corporation, Ohio City Near West Development, and Anthony Rego/Riser Foods was formed in 1997 to develop a $6-million, 35,000-square-foot supermarket with the Saltzman family/Dave’s Supermarket as tenant operator and ultimately owner. The project required a complex site assembly process that involved relocating a Volunteers of America homeless shelter, eminent domain for acquisition, acquiring a substandard grocery dependent on food stamps and liquor sales, and building a new store over the foundation of a historic brewery. Russell Berusch and New Village as managing general partner worked closely with Chris Warren, Mayor White’s Community Development director, local councilwoman Helen Smith, and Ohio City Near West to pull the deal together, including finding a new location for the Volunteers of America (a homeless shelter). Financing was a mix of city and state loans and grants, an equity infusion from Rego/Riser, a loan from VCC, and bank money. This wasn’t a cookie- cutter deal, but it was well worth the effort; the store has been an anchor for Ohio City, serving a diverse customer base while employing 93 neighborhood residents.

“The residents of Ohio City are entitled to the same shopping opportunities as suburban shoppers. By providing good food, quality services and affordable prices, the Dave’s Supermarket family intends to do well in the same neighborhood where our great grandfather Alex sold produce many years ago.”—Dan Saltzman, COO Dave’s Supermarkets

Merrill Building

A key project in the district was rehab of a historic vacant building on West 25th adjacent to the planned Dave’s Supermarket. The building, which contained 21 apartments, was developed by David and Doug Perkowski, brothers who specialized in niche market renovation of older buildings for urban pioneers and creative types who didn’t want to spend Friday’s drinking beer at a suburban TGIF. This was the first multi-family market-rate development in the district. It required a mix of financing sources to make the numbers work: owner equity, historic tax credits, city financing, tax abatement, a construction loan from VCC, and conventional bank mortgage. This successful project was the impetus for the Fries and Schuele redevelopment and similar efforts citywide.

Fries and Schuele Building

In partnership with Ohio City Near West, NVC acquired the Fries and Schuele Building, an historic neighborhood department store building, in 1998. It had been vacant for 10 years and was owned by the Conway brothers of Great Lakes Brewery. NVC purchased the building with an acquisition loan from Village Capital. Private developers had viewed the building as a low-income housing opportunity. We believed that there was sufficient low-income housing in the area, and instead proposed a mixed-use development with 38 market-rate rental units to be converted into for-sale condos. Seeing the potential for a market/entertainment district, we built out ground-floor retail for a trendy bar/restaurant (Bar Cento), owned and operated by Sam McNulty, a young restaurateur who went on to develop other venues in the district, and offices for the Committee for Public Art (now Cleveland Public Art). The project was financed with a mix of Historic Tax credits, various city subsidies, a VCC construction loan and a bank mortgage.

The project’s second phase was acquisition and demo of the adjoining Family Dollar store and parking lot and construction of 40 new condos, conversion of the rental units in Phase 1 to condos, and a new Family Dollar to serve a low-income market, along with an indoor parking garage. The $17 million project was supported by a range of city financing loans, tax abatement, historic tax credits, VCC loans and a $5-million construction loan from Metropolitan Bank.

The Market Square District led to other development, both within the district and in the adjoining residential neighborhood, including market- rate, in-fill housing south of Lorain Avenue–the Orchard Park project.

Orchard Park

Orchard Park was a joint venture between Ohio City Near West and NV to develop 30 green, neo-traditional homes on vacant lots located on several blocks south of Lorain (“SOLO”) near Orchard Park Elementary School. The homes were designed by Paul Westlake/DLR Group and priced to sell in the $160,000 range to younger families and lifestyle singles attracted to affordable cool design and the Ohio City vibe. Scaled to fit into the existing neighborhood fabric, they sold quickly. The Orchard Park model was successfully replicated by other builders on vacant lots in the area.

Neighborhood Anchors

One of the challenges of placemaking is working with anchor institutions to define a neighborhood agenda that works both for residents and institutions whose interests are often more corporate than community. The following three examples illustrate the issues and outcomes of this approach.

Tremont Pointe and Valley View Hope VI Public Housing

Valley View Homes Estates, a public housing, garden apartment complex built in the 1930s and overlooking the industrial valley, was decimated by the Interstate 490 freeway extension, a major detriment to the redeveloping Tremont neighborhood. The public housing authority (CMHA) received a Hope VI grant for a complete overhaul of the estate. McCormack Baron Salazar, who had done Lexington Village in the ’80s, proposed a redevelopment plan consisting of three parts: public housing replacement units on site, low-income housing rental and market-rate housing on the periphery. This integrated redevelopment plan linked the project to neighborhood and upscale, single-family new construction. The design integrated the different housing types and tied the site to the community. It is one of the few projects that are both racially and economically integrated. Tremont West Development Corporation worked with CMHA, McCormack Baron, and the City on the neighborhood plan and community buy-in. A model for how to do it right, this stabilized the eastern edge of the neighborhood without displacement of low- income residents.

Bicentennial Village in Fairfax

Conceived as part of the Bicentennial Celebration intended to hi-lite 200 years of City progress. The area selected for the Village was in the Fairfax neighborhood adjacent to Cleveland Clinic and Karamu House, the city’s iconic African American cultural venue. New Village, in partnership with Fairfax Renaissance, worked with the city on a comprehensive approach including rehab for sale of existing vacant properties, 49 in-fill, new, for-sale homes, and another 200 homes repaired, painted and landscaped. To create a walkable neighborhood, we reworked the street grid based on a pattern book and design by UDA Architects Ray Gindroz. Rysar Homes and Habitat for Humanity did the new construction.

There was never any evaluation of whether the attempt to create a “village” within the Fairfax community succeeded and whether there are lessons to be learned. The plan was carried out, the houses were built, homes were repaired, and the street grid redo created a more walkable neighborhood; a bicentennial event was held, but overall conditions did not change.

I think the uneven outcome was mostly due to the Cleveland Clinic’s reluctance to fully embrace the project, whose involvement was limited to some internal marketing to employees. Transforming conditions in Fairfax has never been a priority for the Clinic. Its 165-acre campus was carved out of the neighborhood, and its long-term interests are more in line with keeping a level of stable underdevelopment at its periphery in case more land for institutional expansion is needed. Whether this remains the Clinic’s modus operandi into the future remains to be seen, but past experience does not suggest a major course correction.

St. Lukes Medical Campus

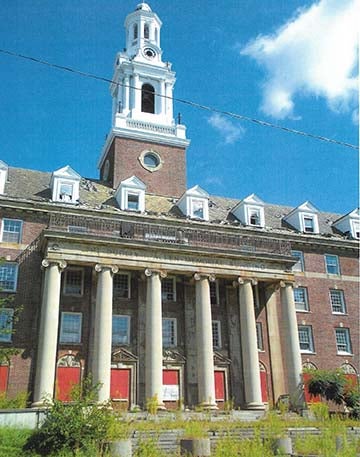

Among the legacy placemaking projects in the city, redevelopment of the St. Lukes campus illustrates the challenges and rewards of doing catalytic development in at-risk neighborhoods. It is a project of scale that involved multiple partners, a range of investors, community engagement, and a great expenditure of time and hard work over several years to achieve what the National Trust for Historic Preservation called a national model for preservation and social equity.

History of the Project

Constructed in 1927 on 26 acres in the Woodland Hills neighborhood of Buckeye-Shaker, St. Lukes was the premier hospital serving the east side of Cleveland and Shaker Heights. (Paul Newman was born there.) The 380,000-square-foot Georgian Revival building was expanded with additions in the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s and ’70s–over 500,000 square feet in total. The hospital supported a corridor of medical office buildings along Shaker Boulevard, the retail district at Shaker Square, and several nearby low-rise rental residential estates.

Population shifts and the economics of healthcare led to several changes in ownership, the last a partnership of University Hospital (UH) and Sisters of Charity that in May 1999 closed the Level 2 trauma center and all surgical and medical services. As there was no requirement to demonstrate community impact, unlike the Community Re-Investment Act for banking, there was no obligation to provide alternative medical services.

When the hospital closed, the Buckeye/Woodhill neighborhood lost its neighborhood anchor, and no one claimed the territory. There were and are a mix of institutions within a half-mile of the site: an RTA station, a Cleveland Clinic special needs facility, St. Benedictine High School, the East End Community Settlement House, Woodhill Estates Public Housing, the Benjamin Rose Institute on Aging, a library, an elementary school, and the Shaker Square and Buckeye retail districts. All were focused on their own silos and had little interest in making community links. The city councilman, who had a record of low-grade corruption and self-interest dealings, was not particularly interested in the site or in that part of his ward. Twenty years earlier, the Buckeye Community Congress consisted of 200 neighborhood organizations and block clubs that would have ended any attempt to close the hospital.

Nonetheless, the community was up in arms, and a proposal supported by then-Congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs Jones surfaced to turn the facility into a Job Corps Center. This was opposed by residents and by the Sisters of Charity, who believed a Job Corps Center wouldn’t serve neighborhood interests. University Hospital wanted out, and a re-development plan was needed.

Development Concept and Project Stages

The original concept was for a project of scale built around a neighborhood landmark with complementary features that would be mutually re-enforcing: a market rate housing development linked to senior housing for parents, health care and supportive services, and an elementary school and library proximate to a middle-income retail district. NPI had funded the Buckeye Area Development Corporation (BADC) under its Strategic Investment Grant program to work on the St. Lukes project and community-building activities in the surrounding area. This was an ambitious undertaking that extended far beyond the original critical path scenario and is illustrative of the challenges of doing hero deals in a legacy city. It also underscores the need for anchor institutions to work together proactively to advance a shared agenda for the community in which they are located and the commitment of resources sufficient to achieve a successful outcome.

Acquisition

We reached an agreement with UH/Sisters of Charity to convey the property to NVC for $1 along with a commitment of up to $7 million to cover demolition, site and environmental remediation costs. NVC would manage the demo.

Demolition and Historic Preservation

In 2005 NVC succeeded in listing St. Luke’s on the National Register of Historic Buildings. Applying for designation meant not demolishing the east wing of the hospital, thereby preserving a neighborhood landmark and eligibility for historic tax credit funding, as well as assuming liability for a 69,000-square-foot wing without a credit anchor tenant.

Development Partnerships

The STL campus eventually became four different projects, each requiring separate agreements with different parties. The core of the project was renovation of two wings of the hospital for 135 units of elderly rental housing and supportive services (St. Lukes Manor). The east wing of the building was to be re-developed by New Village after creating a separate legal entity, with a shared building envelope and agreements on common areas and parking. The 81-unit single-family sub-division was to be done in a joint venture of New Village and Buckeye Area Development. NVC conveyed sites to the new library and school in a land swap with appropriate easements.

Senior Housing

NVC reached a preliminary agreement with Pennrose Development and Property Management out of Philadelphia, which had a successful track record in historic preservation projects and management of housing facilities for the elderly. They agreed to be the managing general partner for the elderly housing portion of the project once we had completed demolition of the hospital additions and our joint application for Low Income Housing Tax credits, and the State Historic tax credit was approved.

The redevelopment was done in two phases, requiring a mix of financing sources including federal and state historic tax credits, along with low-income housing tax credits packaged by Enterprise Social Investment Corporation and purchased by Chase Bank. There also was subordinate financing through VCC. As a result of the Great Recession, HUD created the Neighborhood Stabilization grant program to support “shovel-ready projects” in distressed urban areas which became a key element in the City’s commitment to the development. With funding in place, the historic renovation was completed in two phases within budget, and occupancy and supportive services followed.

East Wing—Offices/Social Services

The 69,000-square-foot East Wing was a major challenge for Linda Warren and her NPI team. There was no development partner, and no anchor tenant. Conventional bank financing was not an option, so this meant piecing together a mix of New Markets tax credit investments and multiple foundation grants, most notably the St. Luke’s Foundation, as well as loans from Village Capital and Enterprise Social Investment. A number of nonprofit tenants were recruited—a top-tier Intergenerational charter school, a Boys and Girls Club facility, and offices for the St. Luke’s Foundation and NPI. Accommodating multiple users, each with differing space needs, in a multistory building presented a range of design challenges and budget issues, all successfully addressed.

Single-Family Market Rate

The original plan for development of an 81-unit housing sub-division was conceived when the Cleveland housing market was at its peak before the sub-prime melt down. There was a range of models and pricing. The City provided new roads, sidewalks, and utilities based on a site plan by NVC. Twenty units were built and sold, and then came the downturn. What was to be a two-year project lasted seven years, and the mix of units changed to include low-income rental units of comparable quality.

Harvey Rice Elementary School and Library

The Cleveland school board was in the process of replacing a severely deteriorated school building on Buckeye and MLK; Harvey Rice Elementary and the Cleveland Public Library had a small, obsolete facility adjoining that they were planning to close. NVC negotiated a land swap, acquiring the old Harvey Rice library and elementary school sites in exchange for land to develop a new library and elementary school at St. Lukes. In exchange, NVC received the library building and the old school site after demo and environmental remediation (later to be redeveloped as a site for permanent homeless housing by the Cleveland Housing Network). The Library and School district agreed to coordinate planning, site issues, and shared common parking. In addition, the Library agreed to keep the old oak tree on the corner, and the school district allowed us to construct a mews between the new school and the East Wing of the hospital so we could provide a direct link between the new housing project and the Regional Transit Authority. The RTA agreed to refurbish their rapid train station.

The Challenge of Hero Deals

Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel economist, in his book, Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow, observes that in larger, complex projects, circumstance, priorities, and commitments change, particularly when multiple partners are involved, and leadership moves on. This means hero deals take longer, cost more and require willingness to go the extra mile when unexpected problems emerge, and stakeholder commitments are tested. This was certainly the case with St. Lukes. Even though NPI attempted to make redevelopment of the Buckeye/Woodhill neighborhood a prime example of our strategic investment initiative approach, our core foundation supporters were lukewarm about the prospects and potential costs—too big, too expensive, too risky, in a neighborhood that wasn’t a priority. As a result, when additional support was needed, they were not very responsive.

The project was as a prime example of the strategic investment program that NPI was championing citywide. There was an element of the “too big to fail” maxim: that the scale would allow us to tap into a bigger pool of resources, and that once underway, stakeholders wouldn’t walk away. This was not unlike CDC thinking about neighborhood hero deals.

Given the effort, risk and time required, this was certainly a project beyond the capacity and risk tolerance for a local CDC. NPI, thanks to the hard work of Linda Warren, her staff and partners was able to pull it off and not bankrupt the organization in the process. It did come at a cost. By diverting our attention and limited staff resources to a project without a strong CDC partner, we were unable to engage the area’s institutional stakeholders in an overall plan for the community. That is only now beginning to take shape.

In balance, St. Lukes was a successful venture. An initial direct investment by our core foundation partners of less than $700,000 in loans and grants leveraged an overall community investment of $105 Million, providing a range of needed community services and an anchor for the neighborhood.

The result was a landmark building saved from demolition and repurposed to provide 136 units of senior housing, 65,000 square feet for a top-tier intergenerational charter school, a Boys and Girls Club facility, office space for nonprofits adjoining an 80-unit, mixed-income, single-family housing subdivision, a new library and elementary school, and an upgraded public transit station. The project, for all its challenges, will be a significant catalyst for redevelopment of Buckeye-Woodhill and surrounding communities and is illustrative of what it will take to bring back neighborhoods on the edge: legacy, community, resilient leadership, commitment, hard work, tenacity, creative problem solving, partnership.

Placemaking City Wide

The above qualities are evident in a range of other placemaking housing developments sponsored by local CDCs in Cleveland neighborhoods that have provided a stable, middle-income anchor for the surrounding community, most notably Reservoir Place, Kingsbury Run, Church Square, and Battery Park.

In addition, neighborhood arts and entertainment districts, by repurposing older buildings with a cultural vibe based on art studios, brew pubs, clubs and galleries, can create places that bring creative types together and attract suburbanites who want to walk on the “wild” side. Examples include Hingetown, Tremont, Detroit Shoreway, Waterloo, and Asia Village. Place making takes many forms, and it is being nurtured in different places throughout the city by urbanists who thrive on the challenge.