Part I

Jewish-Lithuanians

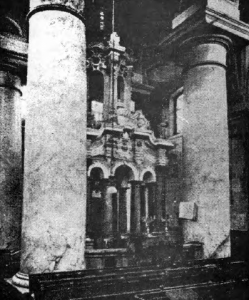

The history of Lithuania would be incomplete without mention of the rich Jewish-Lithuanian culture. Under the leadership of Vytautas the Great, the first charters of privileges were issued to the Jewish communities in 1388 and 1389, and remained in effect for some four centuries.[1] These permitted Jewish-Lithuanians to live as free men. Vilnius, known as the Jerusalem of Lithuania, became a leading Jewish center of culture, education, and political activity in Europe.[2]

Later, however, the conditions of the Jews became severe. During the czarists’ period of rule in Lithuania there were a number of decrees restricting their freedom of movement and forcing them to leave the countryside.[3]

During the independent period, when governmental support was given to all national and religious groups who desired to have separate schools, the political and educational conditions of Jewish-Lithuanians improved significantly. According to Max M. Learson, “In this respect [political] the Lithuanian Jews enjoyed greater rights than those granted to the Poles, the Germans and White Russians, not one of whom had their own ministry.” He continues in regard to education: “Nowhere outside of Palestine did Hebrew make such tremendous strides as in Lithuania in those twenty years. Even after the establishment of the dictatorship (1926) these Jewish schools continued to function at governmental expense.”[4] Further evidence of the governmental attitude towards Jewish-Lithuanians is found in an article in the newspaper, Hasaa, which appeared on March 7, 1940. In part it stated that “On the occasion of the national festival, in the streets were distributed governmental proclamations to the inhabitants explaining the meaning of the festival. It is most important that those proclamations were printed in five languages, among them Yiddish, which made a great impression on the Jews.” The article further praised the attitude of the leaders of the government of Lithuania and their sincere belief “that in the state there is no room for influences and currents that are inspired by race, hatred and persecutions.” It also mentioned the improved atmosphere in contrast to the previous rulers.[5]

With the growth of national socialism in Germany, the Jews throughout Europe became apprehensive. This was further increased by the Nazi invasion of Poland, when many began to flee eastward. Unlike many countries, Lithuania didn’t turn away the Jewish refugees, and the city of Vilnius alone admitted some 15,000 escaping Nazi and Russian persecution. As the Lithuanian government gained full control of the Vilnius area, “systematic measures were taken for the relief of the refugees,” and although the strain of the new arrivals upon the tiny Baltic nation were arduous, “the attitude of the Lithuanian government itself, however, was one of gratifying tolerance.”[6]

Occupation by the Nazis seen witnessed the extreme measures which had occurred under the first Russian seizure of the ceuntry. The Lithuanians were once again faced with incarceration, toture and death. This time, however, the Jewish-Lithuanians were to receive the worst. Nevertheless; encouraged by the Bishops of Vilnius and Kaunas, many Christian Lithuanians risked their lives to protect Jewish-Lithuanians.[7] The extensive Lithuanian underground press also condemned the barbarity of the Nazis. Members of the former Lithuanian government, such as Dr. K. Girnius, an ex-president, and Professor M. Krupavičius and J. Aleksa, ex-ministers ef agriculture, also protested the treatment of Jewish-Lithuanians, and as a result of their actions were arrested.[8]

Unfortunately, to date a comprehensive, scientific study of this period does not exist. There have been some weak attempts to describe the events as they occurred; however, they tend to be slanted, poorly documented, and reflect heavily the author’s predilection. In all likelihood, when a thorough study is completed, it will reveal the extremes of beth the Jewish and the Christian Lithuanians: those who risked their lives to save their fellow man as well as these who showed little or no respect for human life. But in the middle of these extremes will fall the vast majority of the populace, who feared for their lives and those of their family, and therefore tended to be immobile.

Many Jewish-Lithuanians coming to the United States were to become renowned in their respective areas of expertise, and to add to the cultural growth of the country. Proud of their Lithuanian heritage, these include the famous sculptor, Jacques Lipchitz, actor Lawrence Harvey, and folklorist Vytautas Beliajus, more about whom will be described in the next chapter.

Perhaps the best expression of the feelings of many Jewish-Lithuanians for Lithuania can be found in the first two verses of the poem, “To Lithuania,” by Leiba Neidus.

Lithuania, I could not forget her

For from abroad I loved her more

That love no one will conquer

Or tear out that longing so holyYou are like a mother, self-sacrificing

Your exploited sons I love

And their songs plaintive, bewitching

With the innocence holy,

carressing the heart.[9]

- Encyclopedia Lituanica, op. cit., VII, p. 522. ↵

- Joseph Tenenbaum, Underground (New York, 1952), pp. 322-331. ↵

- For one of the better accounts of this situation see: Ezra Mendelsohn, Class Struggle in the Pale (Cambridge, 1970). ↵

- Max M. Learson, "The Jewish Minorities in the Baltic Countries," Jewish Social Studies, III, July, 1941. ↵

- Hasaa, Tel Aviv, March 7, 1940. ↵

- Israel Cohen, Vilna, (Philadelphia, 1943), pp. 469-472. ↵

- Tenenbaum, op. cit., p. 351. ↵

- T. Angelaitis, Who is Worse Stalin or Hitler? (Chicago, 1950), p. 25. ↵

- Alfonsas Tyruolis, Nemarioji Zeme (Immortal Land), (Boston, 1970), p. 138. ↵