Part I

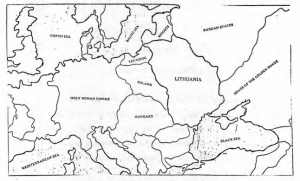

Development of the Grand Principality of Lithuania

After the death of Traidenis, the pagan Gediminas (Gedymin) family came into prominence. The family’s history can be found in German, Russian and Lithuanian folktales, the last of which originated during the Renaissance. The family descended from one of the ducal clans of the Highlands region and their authority eventually spread over all Lithuania. The first member, mentioned in 1291, was Pukuveras. His two sons, Vytenis and Gediminas, ruled successively and laid the foundations for the principality which expanded to the east and south into Slavic lands.[1]

As the Lithuanian state was developing, Tartars ravaged the eastern Slavic nations, destroyed the Kievan State, and moved toward the Baltic Sea exit. Lithuania repelled the attacking Tartars and provided a wall of resistance against the nomadic tribes. At the same time, Lithuania steadfastly resisted the Teutonic Order that attacked the country approximately one hundred times between 1340 and 1377. Wigand of Marburg, the chronicler of the Knights of the Cross, recounts the attacks on the Castle of Pilėnai, its defense, and the heroic death of the Lithuanian soldiers. The description of the battle has been used in several literary works and most recently in the creation of an opera, Pilėnai.[2]

Favoring peaceful relations with the neighbors and hoping to improve economic conditions, Prince Gediminas invited German merchants, soldiers and craftsmen to come to Lithuania, allowing them to settle freely with their families. He also invited farmers, promising them tax free use of the land for ten years.[3] As a result of these overtures, Gediminas was able to conclude a peace and trade treaty with representatives of the Knights of the Cross and other leaders of Livonia guaranteeing merchants unhindered travel throughout Lithuania and Livonia. The 1323 treaty was announced only in “King” Gediminas’ name, an indication of his influence as a leader of a powerful, established nation. The state even had a permanent capital, Vilnius (Vilna, Wilno), which has remained the capital of Lithuania from the time of Gediminas to the present.

Although each of Gediminas’ six sons received designated areas to rule, as was customary in patriarchal states, Lithuania did not split up into principalities as was the case in Kiev, Russia and Poland in the 13th century. Rather, after Gediminas’ death, Lithuania was ruled by two of his sons, Kestutis and Algirdas, who formed an independent dyarchal government and who ruled with an almost historically unprecedented accordance. Especially in the battles with the Order, both participated and negotiated as one. Both sons waged successful wars against neighboring countries. Algirdas, who was ruling the eastern segment, extended the borders of Lithuania by annexing a large part of the Ukraine, and his continual clash with the growing Duchy of Moscow resulted in three wars. These campaigns against Moscow were part of Algirdas’ long range goals as verified by a chronicler of the Teutonic Order who stated, “All Russia ought simply belong to the Lithuanians.” (Omnis Russia ad Letwinos deberet simliciter pertinere.)[4]

The dyarchy ended with the death of Algirdas. Jogaila (Iagailo), the only son and successor of Algirdas, did not agree with his uncle Kestutis and concluded a treaty with the Teutonic Order, promising not to help Kestutis when the Order attacked his lands. At this time of crisis, when it became apparent that paganism was outdated and was to be renounced, Jogaila decided to move closer to the western Church, but the Teutonic Order’s equating baptism with subjugation presented a notable obstacle to accepting Christianity. There was, however, another Christian neighbor, Poland, through which the Lithuanians could once again officially, as a state, reaccept Christianity.

The Poles were looking for a king and a husband for Jadwiga (Hedwig), the successor to the Polish throne. Jogaila was the natural choice. In return for marriage and the throne of Poland, he promised to regain the territories that the Poles had lost; to have himself, all the Lithuanian prince-barons, and the whole nation baptized; and to combine all his Lithuanian and Russian lands with Poland. Jogaila’s baptism and marriage took place in Cracow, Poland, in February-March, 1386, and the baptism of the Lithuanian nation, took place a year later.[5]

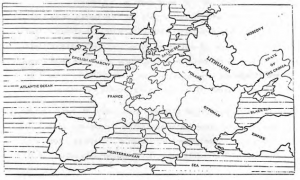

The conversion and union with Poland was a major blow to the Teutonic Order, who did not recognize the baptism and continued to fight the Lithuanians. This war activity forced Jogaila to join his forces with Vytautas, Kestutis’ son who controlled the Lowlands, to embark on a campaign to destroy the state of the Crossbearers. This undertaking by the Lithuanians and Poles, led by Vytautas, ended in the famous Battle of Tannenberg (Grundwald) on July 15, 1410, one of the largest contemporary battles in Europe. Lithuanians, Poles, Czech mercenaries, Tartars and Ruthenians so soundly defeated the Order that its military force was shattered and its push to the east was halted for centuries. Vytautas became the great hero of the Lithuanian nation.

With the 1422 treaty of Melno Lake in East Prussia, the border between the Teutonic Order and Lithuania was formulated and remained unchanged until World War I, with part of it still intact today between Lithuania and the Region of Kaliningrad. The Grand Principality of Lithuania, which was founded by Gediminas and eventually extended from the Baltic to the Black Sea, finally freed itself from the attacks of the Order and, in 1429, with the Holy Roman Emperor offering Vytautas the king’s crown, Lithuania’s development as a modern state became inevitable.