Main Body

Millionaires’ Row: Manners

The lifestyle on Millionaires’ Row abided strictly to “what was expected”. This effected the social events, the manner of dress, and the rituals of daily life. The protocol was learned from childhood and respected religiously. There was never any question as to what was right and wrong. In many ways, the arbitrary rules made life easier.

A Bible for this period was the publication known as Cleveland T own Topics. This weekly review of society, art and literature was launched in January 1888, and monitored the social life for more than four decades. William R. Rose (father of William Ganson Rose) was the editor. Helen DeKay Townsend was the Society Editor. Her name became synonomous with Cleveland social events. During her lengthy regime, it was the custom for the host or hostess to inform her of their contemplated date for an event before issuing the invitation. Prior to the full holiday social season, Miss Townsend published in Town Topics a calendar with dates, hosts and functions . She attended all wedding!?, receptions and balls and her write-ups made fascinating reading.

After 41 years, the Cleveland Town Topics combined with the Bystander, and continued under the latter name. For a lifetime Clevelanders had followed the society columns of Helen DeKay Townsend and the interesting feature stories. The Bystander, founded in 1921, ceased publication in 1934.

Another crucial channel of communication was the Society Page in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. The Society Page announced engagements, weddings, the names of visitors to Cleveland, and who entertained for them -as well as the names of new-born babies. The Sunday edition featured the Society Section, covering several pages. This Section was heavily sprinkled with photos of wedding receptions, describing in detail the bride’s veil, gown and bouquet, the bridesmaids’ dresses and their bouquets -and listing the names of the bridesmaids and ushers, stating where they were from.

The most important time in a girl’s life was the year when she became a debutante -the balls, luncheons, theater parties were endless, culminating in her spectacular “Coming Out” ball. The planning, attending and recording of these events filled our small world.

The social season of my first year out of Yale was a typical whirlwind. That winter season of 1909-1910, besides 22 debutante balls, there were dinners and other parties like the annual Yale Ball, Princeton Triangle Show, and Yale Glee Club Concert. That was my first year of working; office hours were 7:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., six days a week. I attended all the parties, averaging four hours sleep a night -then a hot-and-cold bath and off to work! As it was my first job, I disciplined myself never to be late. But, to miss a party was unthinkable.

Where the party was held was very important. One of the most popular settings for the debutante balls was the Colonial Club. It was situated on Euclid Avenue just east of what is now East Eighty-Ninth Street. It was a beautiful yellow building with white columns. It had many features that made it attractive for family use: a bowling alley, ping pong and billiard-tables, and a shuffle board. But, far more important- it had the largest ballroom in Cleveland, with a large stage for the orchestra. This made it ideal for the debutante party. Many joined the club, if they were not already members, especially so that they could have their daughter’s “Coming Out” ball there.

These balls ran until 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning. Each of them featured James D. Johnson’s society orchestra. About 1:00 a.m. breakfast was served to the dancers still there . . . scrambled eggs, sausage, bacon and cinnamon toast. No detail was overlooked in making the party elegant. For instance, for my sister Helen Wick’s ball, Mother sent over a large number of oriental rugs, which were put down on the lobby floors to make the party more homelike and complement the elaborate decorations.

Chaperoning was very definitely a part of those early days. Many times the girls were accompanied by their parents to the dancing parties. The young girls were not allowed to sit on the country club porch during a dance. My brother-in-law, Andrew Calhoun, was told by his father that he .shouldn’t kiss a girl under his own roof, as she was under his protection when in his own home. He was glad to learn that it was all right for him to kiss a girl under the roof of his car.

The rules of dress were as strictly obeyed as the rules of behavior. During the hectic holiday season, a debutante would be seen at a Christmas ball wearing a white bunny skin coat, and the young man would surely be wearing a black broadcloth Chesterfield coat with velvet collar, high silk hat, and white kid gloves. The men wore their white gloves when dancing. It made a picture in black and white to rival the penguins. The high silk hat and the cutaway were worn to receptions and to Church on Easter Sunday. The opera hat had the advantage of collapsing so one could put it under the seat at the theater.

In 1905, a debutante reception was given for Miss Frances Payne Bingham who later married Mr. Chester C. Bolton. She was later known with admiration as Frances Payne Bolton, Congresswoman and benefactor.

She was given a beautifully appointed reception by her father, Mr. Charles W. Bingham. The charming old house, the main part of which was built years ago by the debutante’s great grandfather, Nathan Perry, was a bower of floral blossoms. The drawing room and entrance hall were decorated with garlands of pink roses and foliage.

The numerous exquisite bouquets sent to the debutante were arranged on the mantel, tables and piano, and fastened to the walls about the room. There were roses of all colors; orchids; and lilies of the valley. There were violets all tied with chiffon or streamers of ribbon.

The debutante held an exquisite bouquet of mauve orchids and lilies of the valley, tied with an embroidered chiffon scarf. Her gown was white satin, with a lace yoke, and her girdle was gold cloth and satin. Miss Elizabeth Bingham, who assisted her father and sister in the receiving line, wore a beautiful mauve chiffon and lace gown. (Miss Bingham later married Mr. Dudley S. Blossom.)

The large library was very attractive with decorations of poinsettia and palms. Punch was served in the hall leading to the library.

Bunches of meteor roses were in the reception room. In the dining room, the mahogany table, set with lace and beautiful silver, had for floral decoration a large crown basket of pink straw filled with pink roses. Refreshments were served in the smoking room from a serving table decorated with a large basket of pink roses and silver candelabra with pink shades. Many of the large houses had smoking rooms, as it was considered improper for a man to smoke in the presence of a woman. At this time women did not smoke.

I wore my cutaway with wing collar, wide ascot, and high silk hat to this and other formal receptions. My opera hat was worn only at formal evening affairs. Easter Sundays, spats were often added to cutaways and high silk hats to complete the costume, by such careful dressers as Bob and Laurence Norton.

A most original fancy dress dancing party was given by two then famous bachelors: Harvey H. Brown, Jr. and Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. It was given in the then new ballroom of the Wade Park Manor. We were invited to a reincarnation party and dressed as we would like to be in the next world. Our hosts were dressed in elaborate wedding gowns (made by Leonard’s mother’s dressmaker) made of white glistening oil cloth with extra long skirt trains. William (Billy) Powell characterized the ridiculous opposite as a ‘Life Guard’, as he was slim and of short stature, not the husky type. I won the album he cleverly made, and have it still in my library. It is filled with Mack Sennett Comedy beauties in their risque bathing suits; entitled, “Girls I’ve Saved”. I went as a black faced minstrel, “The Sheik of Alabam”. John Garfield (grandson of the martyred President) went as a newsboy (with a large supply of seven-column newspapers headed “The Heavenly Herald”, with special write-ups of each guest at the party).

General and Mrs. George A. Garretson entertained for their niece, Miss Helen Wade, at the Euclid Heights Club by giving her a beautiful cotillion.

The club was decorated with foliage and crimson rambler roses.

There were 30 young couples who danced the pretty figures of the cotillion led by Mr. Garretson Wade and Mr. Robert Norton.

Some of the favors were baskets of carnations tied with ribbons, miniature silver yachts, bon-bon boxes, and silver cigarette cases decorated with quaint Dutch figures. The souvenir favors were satin bags for the girls and canes for the men.

Mrs. D. Z. Norton, Mrs. Leonard C. Hanna, and Mrs. Prescott Ely presided at the three tables, which were gay with the bright colored flowers and held the cotillion favors.

Helen Wade’s brother, Gary Wade, led the cotillion. Bob Norton was so good at leading cotillions, he was always invited to be a “leader”.

Laurence Norton was my contemporary, and we were too young at the time to be invited to this party. His brother, Bob, was kind enough to fill us in on the details and gossip from the Garretson, and other, parties.

Each debutante kept a memory book the year she “came out”. It was filled with calling cards of men who had escorted her to parties, and what kind of flowers her escort sent her to wear at different balls. The two most popular corsages were violets and lilies of the valley. Then there were also cards for gifts of American Beauty roses and ten-pound boxes of candy. The younger brothers and sisters liked the beaus best who sent candy.

The dance program (with its tiny pencil) was an important part of her memories. The invitations she received -engraved in all sizes and shapes -to lunch, dinner and theater parties; concerts, receptions and other entertainments, filled the book.

The social graces were not merely limited to large-scale events, but permeated every aspect of the day’s routine. Every encounter had its correct pattern. For instance, New Year’s Day was observed by the popular custom of “At Home” in most of the residences on Euclid Avenue. On such occasions, calling-card etiquette was carefully carried out. Upon arrival, two calling-cards were left on the silver tray in the entrance hall, representing both husband and wife even if he did not accompany her.

I remember my mother putting her calling-cards in her gold mesh bag before going out “calling” in the afternoon. The cards conveyed a language of their own, and the turned down corner on a card had a certain significance:

upper right corner = Visit

upper left corner = Congratulations

lower left corner = Adieu

lower right corner=Condolence

And how did one learn all these intricacies of corner bending? Probably from an elaborately bound and decorated book entitled “Card Etiquette”. This book, clearly designed for the female sex, was compiled by Mr. J. Babcock Harrison, edited by Mrs. Medeleine Sinton Dahlgren of Washington, D.C. and published by Borrows Brothers Company in 1893. There was no doubt the correct use of calling-cards was a serious matter. The first paragraph of the book points out that the card itself should be correct:

“VISITING CARD SIZES, FORM WORDINGS AND CUSTOMARY CIVILITIES:

“The size and shape of cards, also character and style of engraving, vary somewhat from season to season, and in absence of positive directions to the contrary, we shall, in each case, furnish the shape and style in vogue at the time order is received, rather than follow exactly a previous commission. Should, however, an absolute preference be indicated, we shall, of course, deem it our duty to conform to expressed wishes.”

During the Victorian age , books written on etiquette were as popular as books written on sex today. They gave you such needed advice as:

“…how to open your mouth when you are tongue-tied.”

“. . . when to talk about the weather.”

The books on etiquette even warned you against putting your napkin under your chin!

These endless small concerns added grace to ever day life. While the mistress of the house was thus preoccupied with the customs and ceremonies -there were the cadres of devoted servants who staffed the great houses and kept them ready -at all times -in case someone should come “calling!”

My parents had fine, faithful Irish maids. Bridgette O’Riley was our cook for 25 years. We also had an upstairs maid, and laundress. Washington was our colored coachman for 30 years. He also milked the cow and tended the flower and vegetable gardens. Mother always told the story about our cook when she had just come from Ireland. Mother asked her to “dress the turkey” so she could take it as a contribution to the church fair. The order was literally carried out. The cook made a little dress on the sewing machine, and booties for the legs, for a fully “dressed” turkey.

In our mannered, manored life the servant’s time was not his own; there were demands for service day and night. There was the poor parlormaid who had to dust the drawing room tables full of objects d’arts. Any space left on the tables was filled with family pictures in silver frames -that needed constant polishing. This was just one of her many duties. Then there was the careful polishing of all the fine furniture with a mixture of lemon oil and bees’ wax. Vigorous rubbing made a bright shiny surface, reflecting all the objects in the room. Bees’ wax was used for many tasks. It resembled a small cake of yellow soap. Tailors and cobblers used the yellow square on their thread; the waxed thread would then slip through the heaviest fabric or leather. Another advantage of running the thread through the wax was that it created extra strength. A rusty pin or needle stuck into the wax became usable again.

These small tricks helped in doing the many chores, but could not shorten the day for the personal maid. The personal maid helped the dowager to dress in the morning and evening -and helped her to undress when she went to bed. Sometimes it was one o’clock in the morning before she was off duty, if her mistress returned late after the theater and dancing parties.

A maid such as Michele started helping her mistress in the morning the minute she cinched her into her corset. Her shoes had to be buttoned, as she couldn’t lean over in her tight corset. She put the whalebones in the collar of Madame’s blouse, took a suit out of the closet and helped her into it. Next came the hat to be fitted over Madame’s pompadour. She then chose a small veil the color of the hat and adjusted the wispy veil, pinning it in the back with a hair pin. The Mistress then pulled each strand of hair into place with her hat pin because the hat would stay on all day, through luncheon party or matinee. Finally, Michele would brush Madame’s suit collar and hand her the matching pocketbook and gloves.

Michele would help her mistress dress for dinner every night. The ball gowns were made of beautiful satin and silks, weighted down with black jet or white seed pearls and embroidery. She had to fasten them up the back with many tiny hooks and eyes, loops and buttons. It was tedious work to fasten up the evening dresses. Sometimes a choker would be worn around the neck; this was a half-inch wide ribbon fastened in the back with tiny hooks and eyes. If it was very elaborate, it was called a dog collar.

The Italian gardener was a cross between a gardener and a houseman. He took care of the grounds summer and winter. In the spring, when dandelions sprang up allover the lawn, he brought his female relations and their friends to help pick these weeds, from which they made terrible dandelion wine and salads. Every small child in the house was scared of them in their colorful dresses, as they thought they were gypsies who stole little children.

Dominick came in the house to clean the shoes, stoke the coal furnace and lay the fireplaces. The last fire he made, he put the big logs on the bottom, the kindling on top -and the paper on top of the kindling. It was the last fire he made in that house. He was growing old, and more and more dependent on his awful dandelion wine, so they had to let him go .. .

The laundress loved the wine Dominick made. All the wine he brought to the house was given to her. She deserved it, working down in that gloomy lonesome cellar.

She had a low iron stove in which she burned wood. On top of the stove she boiled the clothes and heated the irons. She washed the clothes with yellow workman’s soap, rubbed them on a scrubbing board, put them through a wringer, then ironed them with a sizzling hot iron which she tested with a wet finger.

Mrs. Harvey H. Brown, with her family of three daughters and two sons, engaged an extra laundress in the summertime to keep up with their extensive entertaining. The family was always seen wearing freshly starched golf and tennis clothes.

And, although the laundress may have done her best to keep the outfits looking good, women were handicapped by those long tight skirts when trying to play golf. Those costumes, made of white pique and linen, were generally made to order by a dressmaker. Many girls fainted in the summer heat, standing still for such a long time being fitted for skirts and dresses.

The men wore golf caps and plus-fours (a baggy trouser worn just below the knee), long socks and a striped blazer.

For a woman to be “in style” she had to endure real physical discomfort: the clothes worn in the late ’90s were heavy and held the body rigid. The dresses were too long; the shoes were worn one size too small! The gowns were weighted down with flounces, long fringes of silk, and laden with beads and embroidery, lace and flowers. Then there was the struggle of putting on the long white kid gloves, one finger at a time.

Men were fashion conscious too; on Easter Sundays they wore cutaways and high silk hats. Sightseers came from all over to observe the Easter parade on the sidewalks of Euclid Avenue.

In the ’90s, Cleveland society patronized several tailors. The two most famous -and expensive -were unique in being such opposite personalities. James H. Cogswell was very social, and was listed in the Blue Book of 1895. His competitor, Charles W. Pohlman, was famous for his horses and unusual carriages. He would drive tandem with his two footmen dressed in faultless livery. I presume he did it as a form of advertising for his quality tailoring. Father had him tailor my first long trouser suit.

The smoking of fine pipes was very fashionable and each man would have his own special tobacconist.

My friend , the tobacconist, told me that there were some concerns which made a business of hiring men for no other purpose than the coloring of Meerschaum pipes. This coloring, of course, could only be accomplished by smoking, and there were firms who employed a number of men to do this, paying them at the rate of 20 cents per hour. Of course, such professional smokers had to use mild tobacco in order that they might smoke a long time without getting a headache. I have seen these men at work; they were a queer set. Some were men of high educational attainments, who, being out of other employment, did this for a living. Among such smokers were men suffering from consumption, though this did not endanger the person who bought a Meerschaum pipe later on; all the pipes were carefully boiled and baked, thus eliminating all germs. It was a queer trade, just the same.

The privilege of our way of life was reflected in our schooling. We all attended private schools that were established to serve our special needs. Several of these institutions are flourishing today. Two early schools were the Brooks School for Boys, started in 1875, and Miss Mittleberger’s Boarding School for Girls.

Miss Mittleberger became ill and had to stop teaching for a while. Her students, in order to continue their education, wanted to attend the Brooks School for Boys. They were accepted at the school only to be taught in the afternoons after the boys were dismissed. Three years later, the Brooks School for Young Ladies and Misses opened at 1194 Euclid Avenue over the Chandler & Rudd store. The second floor was for classes, the third for a gymnasium and observatory.

Miss Annie Hathaway Brown, from New York, started her school in 1887. The school desired to “overcome artificial or inelegant modes of laughing and talking.”

The boarders were required to take a walk in the after· noon. Calisthenics were so well thought of, that in the first commencement of H.B.S. the program started with exercises!

Just three years later, Miss Brown married and moved back to New York in the middle of the school year. All the examination papers of the students had to be sent on to New York to be signed by the then Mrs. Sigler.

Miss Mary E. Spencer bought the stone block house on Euclid Avenue and moved the school to 770 Euclid Avenue.

I entered H.B.S. in September, 1893, and was there for five years -first year kindergarten, and then the four primary grades. H.B.S. was co·educational the first five school years until 1910, when University School took the low primary grades and changed U.S. from an eight form to a full twelve-grade school.

Miss Mittleberger and Miss Spencer requested a private street car for their students. They had been compelled to ride on street cars with men smoking on the back platform and, on several occasions, men in the cars had been caught looking at them, according to an account at the time.

The motorman on a car marked “special” would have difficulty recognizing the pupils, so before the system started there was a reception in both schools at which the motorman was introduced to all the young ladies.

Miss Jennie Prentiss, founder of what is now Laurel School, started in 1896 with seven girls who were transported to the school by the school coachman in its carriage. It was first located at Streator Avenue, now East 100th Street.

The school was called the Wade Park Home for Girls. The goal of Miss Prentiss was to develop in the student a trained heart and a trained mind. She said: “The largest sphere of nobility is the home.”

Laurel was designed to be a preparatory school for college. For those not interested in college, there was an English course requiring four years of Latin and three years of Greek.

The fees ranged from $65.00 in the kindergarten to $150.00 for the higher grades for a year.

Mrs. Lyman became the principal of Laurel in 1904. She came to Laurel from Hathaway Brown where she was on the faculty from 1887 to 1904. She taught mathematics and reading.

Laurel’s next school was on Euclid Avenue near East 101st Street, consisting of a yellow house and barn. Mrs. Lyman was a business woman as well as an educator. The first change she made was to remodel the barn. Miss Flinn started her dancing classes in the old barn.

Laurel had an expensive cooking teacher who came once a week from New York. Miss O’Neil came from Boston several times a year to teach the girls deportment and gracious manners. She would watch the line of girls going into chapel to check their posture and conduct; she went around the dining room during the lunch hour to observe their table manners. She was eloquent about courtesy: “not merely the outward form in body and speech, but the sensitive and refined feeling that prompts genuine and habitual politeness at home as well as in public places and in audiences.”

Dr. Samuel King came from Bryn Mawr to teach elocution.

Mrs. Lyman was only about five feet tall. A very pretty woman, she was striking with her young face and white hair. She was beloved and admired by all her students. She was strict and even felt the responsibility of her students arriving home safely. She ordered that all students proceed directly home without loitering in sweet shops. My wife was in her ethics class and will never forget one of her wise sayings: “You make your habits and your habits make you.” Mildred graduated from this school in 1914.

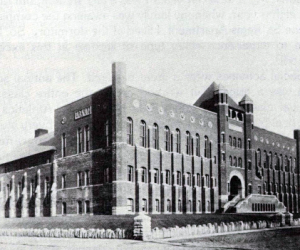

University School was started in 1890 as a country day school, making it the oldest school of its kind in America. It was located on Hough Avenue at East Seventy-First Street, with spacious grounds surrounding it, running from the school up to East Seventy-Third Street and north to Lexington Avenue. The school was considered to be “out in the country”, centered in vacant fields and farmlands. Mr. Newton D. Anderson established the school with an entirely new idea: a school of education with a definite athletic program as well as manual arts training. There was a carpenter shop, a large machine shop, and facility for mechanical drawing. There were classes in pencil sketching, pen and ink drawing as well as in clay modeling and woodcarving. Mr. Anderson was very fortunate in having as a very capable assistant principal, Mr. Charles Mitchell. These two great educators established a school that became nationally recognized.

When I initially entered University School in the fifth grade in 1898, I met the first in a long line of inspiring teachers to whom I’ve been grateful over a lifetime. Our English teacher taught us neatness; our arithmetic teacher taught us accuracy. Miss Roder, our arithmetic teacher, started a club in our class of 1906 called ‘HBR’: Honesty Brings Reward. She made little pins for us by polishing one side of a little ten-cent piece, and put on it the emblem, HBR. We met at different classmates’ homes Friday or Saturday evenings for games and refreshments. Truthfulness was the basic credo of the club and the close relationships helped develop strong friendships among our classmates.

When we were very young, most of us went to U.S. on bicycles or the streetcars, but, when upper classmen, preferred walking to school so that we could pass the Hathaway Brown School and the Mittleberger School girls walking to their daily lessons. My first seven years I was a day student, but during my eighth year, when my family was awaiting the completion of the St. Regis Apartment, I lived at the dormitory. So, I was able to experience every type of lifestyle at this excellent school.

Social activities were a great highlight. The annual senior ball was a huge affair worked on by the entire class; the annual class dinner dance was memorable. Athletics and physical training were also an important factor. Every student was required to participate in athletic programs intramural, interclass teams, and contests. The swimming pool was probably the largest in the city at the time. The varsity teams competed with the local high schools known as the Quad: Central High School, East High, West High and Shaw High. While these public high schools had larger student populations to draw their teams from, U.S. overcame that handicap by having exceptionally capable coaches. And University School was quite often the winner of championships.

Music was an integral part of the school curriculum. Regular courses of instruction in organ, piano, violin, and cello were offered, with individual practice rooms available. The musical groups in the school were choir, the glee club, banjo and mandolin club, and the school orchestra. My devotion to music found much nourishment in this environment.

In 1915 an important University School event took place that should be chronicled here. U.S. celebrated its 25th Anniversary. A huge, gala event was staged, with alumni attending in class uniforms with their year marked, like college reunions. Mr. Elton Hoyt offered a prize for a song to be written in honor of this 25th anniversary. Several songs were submitted , and I was pleasantly surprised to have my song selected for the honor. It’s with pride that I include it here:

PRIZE SONG

by Warren C. Wick, U.S. ’06

FOR U.S. 25TH ANNIVERSARY -1915

Music-Tune: “I Want to Linger”

“I went to U.S. -I went to U.S. to

University School

High in scholarship . . . in character we grew.

First in football, track and baseball too.

Yes, we went to U.S. -we went to U.S. to

University School

And our sons are going there -WHERE?

To University School, to University School.”

Another fashionable mode of education was the “girls’ finishing school.” There were a couple of these elegant schools most popular with the Cleveland damsels in those days. 1909 was the year I graduated from Yale, and I remember vividly in that same year more than 20 Cleveland girls who’d attended Briarcliffe Finishing School making their debuts. I remember it so clearly because of the endless balls, receptions, tea dances, and dancing parties that marked these occasions.

My wife, Mildred, attended the famous Miss Porter’s Finishing School, and she has been kind enough to share her remembrances of that special world:

“Over a hundred years ago there were many girls from Cleveland who went to Miss Porter’s Finishing School. Mrs. Mark Hanna, wife of the Ohio Senator, and Mrs. John Hay, whose husband was Secretary of State, went there.

“Most of the girls I knew, including my cousins from Charleston, South Carolina, attended these prestigious boarding schools.

“Many of the boarding schools were located in the quaint New England villages. Miss Porter’s school, founded in 1839, is in Farmington, Connecticut, near Hartford, with Episcopal and Congregational churches on the main street.

“There were no school uniforms required when I went to Miss Porter’s school. The only sign of wealth I noticed was a solid gold bureau set brought to school by a girl from Long Island. There was no pressure put on you to achieve high marks in your lessons. You could study as hard or as little as you desired.

“Classes were over by Saturday noon, and didn’t start up again until Tuesday morning. We did have study hall on Monday

afternoons.

“Mrs. Keep, our headmistress, very much corseted, very erect, was formal, correct in her dress and manner, and strict in discipline. She would never demean herself to mark her students in the manner of the headmaster of one of the eastern schools. That gentleman gave high marks to all his pupils; he said it “encouraged the boys and pleased the parents.”

“There were not any athletics except horseback riding and tennis. I ruled out riding, as I was frightened by horses and had nightmares about them.

“During the fall, we walked on paths covered with rustling leaves alongside the Connecticut River. On the way home, we would have a glass of cider at the Old Mill. On cold winter afternoons we walked up the hill to Grundy, our tea house. The warm gingerbread and hot chocolate were delicious.

“Sunday mornings we walked up the hill to the Episcopal Church. The minister read long dull sermons to which we listened with polite attention, as was expected of us. The other girls went to the beautiful old Congregational Church a block from the school.

“Miss Palacer would come up from New York once a month and spend an evening at the school. She would make us walk with books on our heads to give us good posture. She taught us how we should act when presented to the Queen of England, how we should curtsy and walk backwards when leaving the Queen; no one should ever turn her back on a Queen. Many debutantes were presented at the Court of St. James, and these lessons were helpful to them.

“It was serene and peaceful at Farmington, and I don’t remember any problems or problem girls.

“The alumnae of Miss Porter’s school became leaders in civic affairs and were deeply inters ted in our cultural development. They did much to improve our art museums, art schools, symphony orchestras, ballet and Metropolitan opera. They gave of their time and money to charity and were continually striving to find ways of making life easier for the underprivileged. I am glad to have had my ‘roots’ in Miss Porter’s school, where I learned noblesse oblige and compassion for the poor.”

Our schooling did not begin and end though with our private schools. There was, of course, dancing school! The headquarters of the Gattling Gun Armory, located near what is now Carnegie and East Forty-Sixth Street, made an ideal setting for Miss Standish’s Dancing School. The spacious hardwood floor was the proving-ground for all the children of Millionaires’ Row. Miss Standish was a very charming woman who ran a very tight ship. Although a very formal dancing class, requiring the boys as well as the girls to wear white gloves, somehow we all seemed to admire and love her, and respected her strict orders.

I often used to walk to the dancing class, collecting my groups of friends along the way. We would eventually arrive en masse at the Gattling Armory for our lesson. When Miss Standish retired, after a decade of teaching, her dancing school was inherited by Miss Eleanor T. Flinn, who acquired her own devoted following over the years.