Main Body

Millionaires’ Row: Meanderings

How we got from place to place in the pattern of daily life is a whole story in itself. Of course, our horse-drawn carriages were the essential vehicles in those early days. But the developing urban life demanded alternative modes of transportation. I grew up witnessing this dramatic evolution into modern technology.

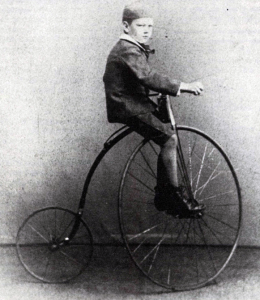

Bicycles were an early innovation, attracting a clientele mainly of adults rather than children. Bicycles, considered to be the machines that most efficiently and economically utilize human energy, had their origins in the early 1800’s in Europe. The first bicycles were made without pedals; one sat on the low seat and propelled the contraption with his feet.

The first bicycle I remember belonged to my brother, Dudley. He got his bike in 1890; my father’s diary records the fact that the front wheel was 54 inches in diameter and the small rear wheel was about a foot high. It had no chains, just a seat, with pedals affixed to the axle of the huge front wheel. This type of vehicle was known as the “ordinary” bicycle. In order to get onto his extremely high bike, brother Dudley found it necessary to mount it from one of the stone steps on our side porch. My brother was over six feet tall and, I, as a little boy ten years younger, felt he was high in the sky, riding on his bike.

Many of the pioneer auto manufacturers first started making bicycles. Cleveland was a thriving center for the bicycle industry. Bicycle shows were held annually in Gray’s Armory and among my button souvenirs are the names of these early manufacturers: Winton, White, Cleveland, Stearns, Eclipse, Rambler, Warwick, Hoffman, Ide, Holiday, Gunning, Henley, Crescent & Sherman -all made in Cleveland.

I remember the day Father took me to the Winton bicycle factory on Perkins Avenue and bought me my first bike. The year was 1896; the color (of the bike) was maroon. I was so small I couldn’t reach the pedals on the men’s model, and so had to settle for the ladies’ model, with the slanted bar. I rationalized that mortification by convincing myself this model was of stronger construction. By the time I got my first bike, it had the two wheels of equal size and was chain-driven. This type was known as the “safety” bicycle. I still have my bicycle kerosene lamp, called the “Search Light”. It is made of solid brass, heavily scrolled with intricate designs. The magnified lens increased the light on the road ahead. The red and green jeweled windows for the port and starboard sides easily slid open to allow the lighting of the wick. My lamp is now a museum piece -over 80 years old.

Learning to ride a bike was as serious an undertakinq as later learning to drive a car! There were several bicycle riding “academies” where one could go for professional instruction in the art. Davis, Hunt and Collister was the largest hardware store at the turn of the century, located at Prospect and Ontario Streets. On the fourth floor of their establishment was a “cyclerama” -a huge circular facility where the art of bicycle riding was taught.

The problem with the chain-driven bicycle was that trousers and skirts were always getting c;;aught; U-shaped clips were worn on the trousers to avoid this. In the early 1900’s The Columbia Bicycle did away with such exposed chains, introducing the “Columbia Chainless”. It used beveled gears in an enclosed housing.

Bicycle rides and parties were very popular. One physical problem was finding a street smooth enough to safely ride bikes. Euclid Avenue, with its beautifully cobblestoned thoroughfare, was a torment for cyclists. One ideal street was East Prospect Street, running from East Fifty-Fifth Street to East Eighty-Ninth Street. It was paved with asphalt, making it smooth and attractive for cycling events. For the evening rides, kerosene lamps on the bikes provided the required illumination.

A whole fashion grew up around cycling. I remember my parents had their tailors make special bicycle outfits Father’s suit had knickerbocker knee length pants, with colorful long hose as accessories. There were gay parades with decorated bicycles. At the famous Glenville Racetrack, bicycle races became popular on the one-mile track, with enthusiasts filling the large grandstands.

An early form of mass transit was the horse-drawn streetcar. I can remember those rumbling cars passing by our first house on Superior Avenue when I was a tiny child. In 1883 a franchise was granted which permitted the East Cleveland Railway to extend its line from East Fifty-Fifth to Doan Brook, and the following year to what is now East One Hundred and Seventh Street on Euclid Avenue. In 1883, the Payne Avenue line opened with horse cars. The Superior Street line was built to East Seventy-Ninth. Of all the street car lines in Cleveland, it came to be the most converted line: first horse cars, then cable cars, then electric trolleys, then trackless trolleys and eventually gas buses.

In the ’80s, ’90s, and into the turn of the century, no streetcars were permitted on the section of Euclid Avenue designated as Millionaires’ Row. Such transportation would have been considered a vulgar intrusion into the elegant neighborhood. To allow the streetcars to circulate, a private right-of-way was created 500 feet west of East Twenty-First Street. The streetcars left Euclid Avenue at that point, went through the right-of-way to Prospect, and then continued out on it, finally turning north back onto Euclid at East Fortieth Street. So, when we lived on Millionaires’ Row we were insulated from this means of public transportation.

The Street Railway Company circulated petitions occasionally, striving to get permission to operate streetcars on Millionaires’ Row. But the property owners regularly refused until most of them had moved away.

In the summertime, the old streetcars had open cars for the comfort of the riders. These were eventually replaced with more modern vehicles. The passing of the old-time open cars on which the passengers sat close enough to the front to be able to reach the motorman with either canes or umbrellas was seen as a definite blessing to the men who operated those cars. An old employee of the Big Consolidated Railway, commenting upon the plight of the motorman, said: “In those days, when the open car season arrived, we found we had to accustom ourselves to having our backs covered with black and blue spots and to having holes occasionally punched through our coats from jabs given by friendly passengers. This was before the days of the electric push-button signal on the cars. Passengers invariably prodded my back with the sharp ends of their umbrellas or parasols to signal that they wanted to get out at the next corner. ‘Don’t bother to signal the conductor,’ I have often heard one woman say to another. ‘Just poke the motorman!’ In such cases, I would turn around to remonstrate after receiving a poke. The woman would be likely to declare to her friend that motormen were the most disagreeable people she ever met. The new cars and the new push-buttons are a great blessing!”

It was a technological breakthrough when one could stop a streetcar by standing up and pulling on a narrow cord. It ran the length of the car, sounding a bell to signal the motorman when to stop.

The streetcar turn-around terminal was at the foot of Cedar Glen. There was a small building on the north side of Cedar Avenue where the motormen and conductors waited to board their assigned streetcars. Inside was an iron coal stove to keep them warm in winter. The streetcars were also equipped with small iron stoves and, when stopping by the building, the conductor would bring from it a bucket of coal to fuel up the streetcar stove. The terminal also had a waiting room for passengers.

On October 11, 1889 the Superior and St. Clair street railway companies were consolidated by the Cleveland City Cable Company. Cable power was introduced at enormous expense, in constrast to the far less costly horse-cars. I remember what fun we young boys had watching them dig the deep channel to accomodate the cables in front of our house on Superior. We used to slide down into the trenches when the laborers were through with their daily work. This channel would carry the heavy wire cables on iron wheels placed at frequent intervals to power the new streetcars. The two main lines constructed were on Superior and Payne Avenues. The Superior line ran between West Ninth Street and East 105th Street. The Payne line extended to East Fifty Fifth Street, then out Hough Avenue to Cable Park, where

that lovely pond for rowboating was.

The cables were driven from the Power House, a large brick building at the corner of Superior and East Forty·Ninth Street. My parents would take me on the cable car to the Power House and I was thrilled to watch the giant wheels (carrying the cables) revolve, powered by powerful steam engines. The noise was deafening, but the operation was fascinating. Father’s diary states, “Cable service began December 17, 1890.”

The cars were operated from underground cables driven from this large Power House. The “grip” controlled by the motorman’s lever propelled the cars as fast as twelve miles per hour. The long lever was sturdily built, extending from the moving underground cable up through the floor in the center of the “grip” car, where the motorman stood. The first “grip” car was always open, making it cold for the motorman in the winter; but the conductor had a more sheltered car, open in the summer and closed in the winter.

By the turn of the century, the Superior and Payne Avenue lines were electrified, with overhead trolley wires installed. Cable cars were discontinued after this innovation.

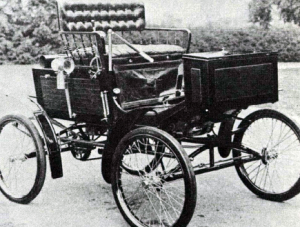

Moden life was accelerating; the nineteenth century came to a close with some dramatic events. In our personal life, a most dramatic event in 1899 was when my father got the first automobile ever seen on Millionaires’ Row. Father bought a Locomobile Steamer; this same 1899 model is on permanent display in the Smithsonian Institute. This exciting creature was built by the Locomobile Company in Westboro, Massachusetts. It was constructed with two welded bicycle frames on which was mounted a Stanhope body. This wooden buggy carriage body was built high off the ground to accomodate the fourteen inch boiler under the driver’s seat! It had a twin cylinder simple engine and was tiller-steered and chain-driven. It was a very high step to get onto the seat built for two.

This Locomobile consumed water at an astronomical rate; it needed refilling every 20 miles. Father paid $600.00 for it, which was no real bargain considering the crude construction. The wire wheels were not much more than bicycle wheels with wire spokes that broke too easily, especially on the cobblestones of Euclid Avenue. One thing to be said for it was that it was a quiet car. The only noise was a gentle hissing sound similar to the steam escaping from a tea kettle spout. The car was propelled by steam, leaving a jet of silver vapor on the ground behind the car.

In 1901 the Locomobile Company moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut and sold 400 steamers in England, making it the largest fabricator of its kind in the world. But, the prestige of the company was small comfort to Father; knowing he was sitting over a boiler of live steam did not inspire a sense of well-being.

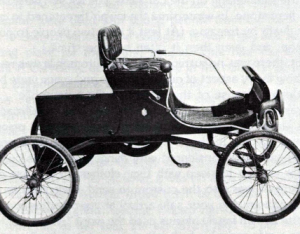

Having made the break with the horse and carriage, but, having found the Locomobile wanting, what was he to do next? I remember sitting with Father while he was reading and explaining an issue of The Scientific American magazine to me. The front cover featured a picture of a new horseless carriage invented by Mr. R. E. Olds. The Oldsmobile was soon to be marketed, and the cover sported the characteristic curved dashboard of the handsome car. I asked, “Do you think we might ever have one?”

In July of 1901 Mr. Dudley B. Wick received delivery on the first Oldsmobile to arrive in Cleveland. My father was surely not the richest man on Millionaires’ Row, but he seemed to be the most adventurous when it came to taking on the new technology. The 1901 model Oldsmobile was built like a buggy. It had a curved dashboard which was an exclusive characteristic of the Oldsmobile. It had one cylinder. The carburetor was clear glass, the size of a jelly glass. It was cranked by a handle on the outside of the car by the driver’s seat, very much as Victrolas were wound. The brass horn blown by a large rubber bulb was on the outside of the car next to the driver. The radiator was horizontal under the floor. The tires were mounted on what looked like bicycle wheels, with those easily broken thin wire spokes.

The next year, Oldsmobile improved the model by adding a do-ci-do seat, holding two extra passengers behind the front seat. It had a footrest to hold the rear passengers’ feet firmly as a safeguard against their being thrown out of the car. The price on that first Oldsmobile was $600.00; the dealer was the Ralph Owen Company, located on the present site of the Bulkley Building.

Tom L. Johnson, the populist mayor of Cleveland, saw the trend toward the future and owned the first two-cylinder Winton in Cleveland in 1902. He was seen all over town, campaigning and attending political events in his new automobile.

In 1904 only half the population had yet seen a horseless carriage. Autos were considered playthings of the rich, and created class feeling. They were considered a fad and not practical enough to last long. Especially in the countryside there was a great rebellion against the auto. When cars would pass, horses would rear up in fright, or start to gallop, causing the farmer great consternation.

As the interest in automobiles intensified, and as more people made investments in them, a wardrobe was invented to fit the mode of travel. The men wore caps, tan dusters and goggles, when riding in open cars. The women covered their hats and faces with large chiffon scarves which held their hats on and protected their faces from the wind and sun. (The dead-white face was fashionable, and only women working in the fields were sunburned or brown.) The women also sported long tan dusters.

It wasn’t easy driving the first cars on the road; there were many hazards and difficulties to overcome. Before there were service stations, it was important to carry a can of gasoline along in the car. Father kept a large steel drum of gasoline with a brass spicket in our barn. Batteries required distilled water.

The tires caused the most trouble. In 1901 Father’s Oldsmobile and other cars had bicycle wheels with wire spokes. The wire spokes would break off and damage the tires on the rough cobblestone streets. The very next year, Oldsmobile offered artilliary wheels with wooden spokes. The early tires used at that time had a simple, understated slogan: “Morgan and Wright tires are good tires.” In 1906 B. F. Goodrich Company developed the first guaranteed tire. Their Silver Cord Tire was guaranteed for a thousand miles. It was adjusted on the basis of a thousand miles of use. For example, if the tires ran 500 miles and then had a puncture, Goodrich replaced them at 50% less.

The cobblestone roads, ruts in dirt roads, glass and nails, would all cause flat tires. There was an ominous hissing sound as the air went out of the tire, and you were jerked to an abrupt stop. The tires weren’t too heavy to lift -but they were dirty and dusty. It happened too often when I was dressed in the formal attire of that era -dark blue coat, white flannel trousers and straw hat -and all would get soiled.

My procedure when a tire went flat was first to get out my repair kit of cement and rubber patches, then repair the hole in the tire with some cement I squeezed out of a tube onto a small piece of rubber. I would then drive the car back to the dealer and have the hole galvanized.

One day Mr. Walter White was driving along a country road when one of his tires went flat. He did not have any patch and cement to mend the casing. Tires had no inner tubes in those days.

He was an inventor though and a man of ingenuity, which served him well in such a predicament. He walked to a nearby farmhouse and bought some oats. Stuffing the oats in his flat tire, he drove slowly home.

Cleveland had become a great center for car design and manufacture. The Cleveland Town Topics gives a detailed account of a special day devoted to this new mode of transportation:

AUTOMOBILE DAY AT THE GLENVILLE TRACK May 7, 1904

“Automobile Day at the Glenville Track will have an exhibition of racing cars manufactured in Cleveland, since Cleveland manufacturers have built and raced successfully more fast cars than all other manufactureres in the United States. This feature should be full of interest. The Winton Bullet No.2 and the latest Peerless racer will not be avail· able inasmuch as both will then be in Germany preparing for the Gordon Bennett International Cup Race. But there are many other fast cars here with which to make up a fine entry list. Among these are the Winton Bullets Number 1 and 3, the Peerless Canary Bird, the White Snail and Turtle, the Baker Torpedo and the Stearns Flyer. The Bullet Number 1 was built in 1902 and was at that time the fastest racing car in America. The Bullet Number 3 was constructed last year and has proved itself the fastest car in its light weight class.”

The Peerless Canary Bird was in competition in 1902, while the White Snail and Turtle raced successfully last year, proving themselves to be the fastest steamers ever made. The Baker Torpedo has never been beaten in a race of electric cars. The Stearns Flyer was a double winner at the Automobile Club Races at Glenville last fall.

It is proposed to have these cars shown by their respective inventors and speeded up to their limit. The sight of Mr. Winton, Mr. Roland White, Mr. Walter C. Baker and Mr. Frank B. Stearns each doing his best with the racing car of his own manufacture would certainly not lack for novelty.”

It was also on this famous Glenville Racetrack that Barney Oldfield established his famous fast-speeding record of a mile a minute in an auto called “The Bullet”.

Climbing up a hill was a challenge to a one-cylinder car. Cleveland, being flat, made driving easy. Mr. Walter White, in 1907, drove his White Steamer as far away as Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania to demonstrate how his car could travel up a mountain road. Crowds gathered from distant points and stood on either side of the road’ to watch and applaud this daring feat.

In 1909 Father gave me for my Yale graduation present a Model T. Ford, a beautiful car with brass radiator and oil lamps. Fords were hard to drive and to crank. Sometimes they would reverse and kick back, often causing a broken arm or sprained shoulder.

The Fords would heat up on the rutted, dirt country roads, requiring one to stop and let the over-heated engine cool off. A can of water and a can of gasoline were usually carried. The radiator cap was taken off slowly to avoid being burned by hot steam.

Another difficulty in winter was keeping one’s car from freezing, and I took the following precautions: I added alcohol to the radiator, and, when parking outside, kept the engine running and placed an auto robe over the hood.

Billy Breed, the son of an Episcopal minister of St. Paul’s church, drove a Mercer. There were many kinds of big brassy horns, though the most unusual horn was the Klaxson. The characteristic toot-toot of these horns identified the owner. It was a personal world of individuals expressing themselves.

In 1909 several makes of autos added a rumble seat. It was placed behind the front seat for the passenger to face backward. Inside the rumble seat was storage space for tools, a pump and repair kit for tires.

There was no top for the rumble seat, and the occupant would be wind-blown, sunburned and rained on according to the weather.

A change in the weather also affected the life of the chauffeur, who zealously stood guard over the seven-passenger open touring car limousine. Such a car became standard equipment for each family on Millionaires’ Rowand, as I have mentioned, we knew who was in any given shop by recognizing the car and chauffeur parked outside. If the Mistress and family were doing errands when it suddenly looked like rain, the group of chauffeurs in front of Halle’s or whatever store would spring to action. They all helped each other, with even the doorman pitching in, to button and snap all the windows onto the huge car. All the large and small cloth flaps with their little Eisen glass windows had to be quickly secured. If by any chance it was a warm day, while you might be snug inside away from the rain, it would be nonetheless unbearably stifling behind all those flaps.

Even though an open car meant so much work, there was great opposition to a closed limousine. It was believed that opening windows would cause a draft behind your head, giving everyone a stiff neck. There was also opposition to having a heater in the car, since that would deprive you of fresh air.

There was a dedicated group of people who would drive nothing but convertibles. With the top down in summertime, and the sun beating on the car seats, you felt you were sitting on a fiery stone. In wintertime the icy air threatened to cause your death by freezing. (At first it took two people to put up the top, and even then it often became stuck.)

But, there was no turning back; the automobile was revolutionizing every aspect of our lives. Time and space were being reordered because of the advent of the automobile.

Train travel had an aura of adventure about it; railroad stations were the settings for dramatic greetings and poignant farewell scenes. In those early days, railroads were greatly feared and were considered very dangerous. It was customary for women to sleep with their clothes on, in case of an accident. It was also the custom to send a telegram to your family announcing your safe arrival at your destination. The Fayette Brown family always used the word “Ancestor” to indicate a safe arrival, which left nine more words allowed in a straight telegram message unused.

Originally, the Pennsylvania Railroad crossed Euclid Avenue at the intersection of East Fifty-Fifth Street, on its way to the Union Depot. When the gates would go down for the frequent passenger and freight trains, all the traffic was stopped on both sides of the tracks. The horse-drawn carriages and wagons, street cars, bicycles and pedestrians, all had to wait for the gates to go up. Since this was an important crosstown artery, with many good stores and theaters, the constant stoppage was intolerable in such a busy area. The heavy demand to eliminate these delays finally forced the Pennsylvania Railroad to build new elevated tracks at this juncture. Raising the tracks over Euclid Avenue allowed the traffic to flow.

About this time, the Pennsylvania Railroad built its large East End Depot at this southeast corner. It proved a great convenience over the main Union Depot location, and was very popular with travelers to and from Pittsburgh, Washington, Philadelphia and New York. This Fifty-Fifth Street Station and the Doan Street Station (East 105th Street) near Bratenahl, were filled with young people traveling back and forth to eastern schools and colleges. It was a gay and happy meeting place for the young people. Yale had the largest alumni in Cleveland of any other city in the country, so there was a preponderance of Yale students.

This reminds me of a charming story concerning my brother-in-law, George Calhoun. George was extremely shy, especially around the girls. During one Easter vacation, a pretty and vivacious girl, “Buttons” Boardman, was visiting Cleveland from the east. George was attracted to “Buttons”, and planned to see her off when it was time for her to take the train home. His chauffeur drove them to the East Fifty-Fifth Street railroad station. George helped her on the train and went with her to her seat. He sat down next to her -and never moved until the train arrived in Philadelphia, where “Buttons” lived! He then sent a telegram back to his family saying he was taking the night train back to Cleveland.

Train travel had certain elements to it -some expected, some unexpected. The trains lumbered along, often having to stop for water and for refueling with coal. The Harvey Restaurants were a landmark for trips out west. I loved the Pullman cars, and the porter’s ritual in making up those upper berths. It was superhuman the way the porter in his crisp white jacket could reach the upper berth and dislodge the bed from the ceiling. Inside were snowy sheets and pillow cases, large pillows and brown clean-smelling blankets. He would reach across the mattress and begin his skillful making of a tight, shipshape bed.

The sleeping compartments on the trains reminds me of a true story that was told to me concerning a prominent Clevelander when he was ‘sowing his wild oats.’ The gentleman in question walked forward several cars in his pajamas and bedroom slippers to crawl into a berth with a lady friend. He forgot that at Albany the train was divided: the part the lady was in, going to Boston; the part his clothes were in -going to New York. Upon arrival in the wrong city and without any clothes, he pretended he was very sick. He called for an ambulance and had himself transported to a hospital for refurbishing.

The folklore of trains is also enriched by an anecdote of my father-in-law. He had a small amount of whiskey in a flask which he was about to drink, late one afternoon, while on a train. He noticed a friend and felt he should share the remaining whiskey with him. Father gave his friend a glass and told him to pour himself a drink. Father, seeing how the friend had nearly emptied his flask, and with quick thinking, said, “That will be plenty if you’re pouring that for me.”

Romance, tragedy, opportunity . .. all possibly awaited you on the train, or at your destination -making every trip a potential adventure.