Main Body

My Family

The first to come to America was John Wick, Sr., who left Wick Court, England, and arrived on the coast of Massachusetts in 1620. We learn of my devout forbearer and his wife being part of the Plymouth Colony, where he embraced his religious beliefs. In 1639 he was received as an inhabitant of Aquidneck, a part of the grant given to the Duke of Warwick in Rhode Island. In 1667 he was killed by the Indians during King Phillip’s War. His grave may still be seen; his descendants are numerous.

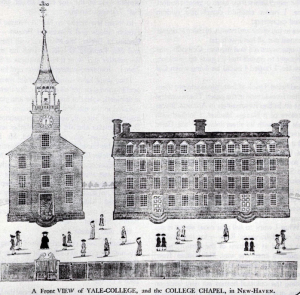

John Wick III graduated from Yale College in 1722. There were eight in his class, all with typical English last names, but six with Biblical first names. The Reverend Stephen Steele, who was graduated from Yale College in 1718 (seventeen years after Yale was founded), was my maternal great, great, great, great grandfather. Officials at Yale University think it likely that my Wick and Steele ancestors knew one another, as New Haven was such a small community in those early days.

Many who have visited in Morristown, New Jersey, are familiar with an anecdote from Revolutionary War Days. Temperence Wick is still remembered as an avid rider and lover of horses. It is told how she saved her favorite saddle horse from being stolen by the British soldiers by hiding her horse in her dressing room! The horse’s deep shoe imprints still show in the floor, much to the amazement of present-day visitors.

Connecticut was a very small state and could not compete in square miles with her larger Commonwealth neighbors. So the Connecticut Land Company was formed to send out settlers to the Ohio wilderness to establish the Western Reserve for the State of Connecticut. John Young headed the scouting party. A surveyor was needed and Henry Wick, Sr., who had studied surveying, volunteered. As they traveled out west through Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) and up north through Marietta, Ohio, they came to the Mahoning River. As it runs practically east and west, they designated the river as the new natural southern boundary of the New Western Reserve for the State of Connecticut Land Company. In 1797 Frontiers· man Young built a cabin on the river bank, laying out the plan of a village that would grow to be a town bearing his name. The main street of Youngstown was named Wick Avenue for my great grandfather, Henry Wick, Sr., who was known as the “Pioneer Merchant”.

A frontier post was established by these early pioneers to trade with the Indians. It was very difficult to travel to the eastern seaboard to purchase commodities for their store. My great grandfather made many trips back and forth in the next few years on horseback or wagon. Quotes from two of his letters to his wife, Hannah Baldwin Wick, describe the hardships of traveling through that wilderness:

Pittsburgh, Saturday, 16, Sept. 1809

“My Dear:

I arrived here this afternoon about three o’clock and am in good health. I expect to start for the city tomorrow morning in company with two brothers, gentlemen from Kentucky, of the name of Reader; recommended by Mr. Thomas Cromowell, from this place, to be very steady, decent men…

I expect you need not look for me in less time than five weeks from the time I start. I am in hopes that the children will conduct themselves in a manner that they may be applauded at my return. I am,

Yours affectionately,

Henry Wick”

Philadelphia, April 5, 1815

“Respected Dear:

I arrived here last Thursday evening in the stage from Lancaster, after a long and tedious journey. I stayed in Pittsburgh one day on account of the rain and the roads, and the road was extremely bad.

I overtook Robert Gibson about six miles below Greens· burg, and the roads were so bad that he will be about a week later in the city than expected. Hawling has fallen. $6.00 is now given for haw ling to Pittsburgh, and but a few country merchants are buying goods, and there are but a few arrivals. But it is expected that in a course of two weeks at the farthest, there will be goods aplenty, and I think to content myself here and see the arrivals if they come in two or three weeks.

Many of the goods here are as cheap as ever they were, and others are high and some not to be had. I put up with my old landlady, Mrs. Davis. We have plenty of fresh shad and oysters when we choose, and I now live well and enjoy good health.

I expect to attend a large sale next Tuesday of new goods. On Monday we get a catalog of the goods and the privilege of examining them.

If I stay a week or two longer than I expected, I think the boys may attend to the business at home as well as if I were there. If you think it any advantage you may sell the best Calico for 80¢ per yard; the best pins for 25¢ per sheet, and the blue papers for 18 1/2¢. Teas are still high.My pen and ink is so bad that I think it is best to quit, and remain as ever, your affectionate friend and husband,

Henry Wick”

Regarding the boys that he refers to in his letters, all eight of his sons were exceptionally fine and cooperative. Two of them later came to Cleveland, each to found his own successful bank and to be its president. Lemuel in 1845 was the first President of the National City Bank of Cleveland, and Henry, Jr., my Grandfather, in 1847, was President of the Wick Banking and Trust Company. They were both hard workers and actively helped to develop Cleveland.

Many of the Wick men were active in the iron and steel business of Youngstown. They founded Republic Iron Works, now Republic Steel Corporation, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company and Trumbull Steel. Some were responsible as presidents of these companies; other Wick family members were officials and directors.

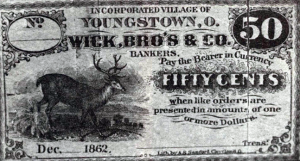

The original family store remained a commercial focal point in the rapidly growing Youngstown community; the Wick Brothers Bank began its long history for safety and service. Henry Wick Sr. was President of the Bank, which issued its own money, as was the practice of private bankers in those days. Its money was always quoted ‘above par’, which showed its strength.

My great uncle, Lemuel Wick, while yet only a few months old, was brought on horseback by his mother from his native place in Pennsylvania to Youngstown, Ohio, in 1804. After growing up, he received his M.D. degree from Yale College and about the year 1825 he began his medical practice in Youngstown. He was a very popular physician and soon built up a large practice, in the execution of which he greatly injured his health by riding over the country roads day and night. About the year 1828, he ceased the practice of medicine and entered the mercantile business in Youngstown with his brother. In a few years, he assumed the entire business himself when his brother retired from the firm. He was elected a director of the Western Reserve Bank in 184l.

Lemuel Wick felt that Cleveland had a bigger future than Youngstown. He tried to persuade his next younger brother, Henry Wick Jr., my grandfather, to join him in the venture to move to Cleveland and start a bank. But Grandfather, having five children and having started working for his father when fourteen years old, felt he had better stay in Youngstown and continue with the Wick Bros. Bank. But Lemuel left in 1845 and went to Cleveland and a little later started in The City Bank of Cleveland. The National Bank Act was signed by Lincoln in April 1863. Lemuel secured a National Charter January 20, 1865 and changed the City Bank name to The National City Bank, and he was its first President. It is the oldest bank in Ohio and also the largest National Bank.

Lemuel kept writing his brother Henry, Jr. that his bank was progressing successfully and that he needed him.

Finally in 1847 Grandfather decided it would be good for his family to move up to Cleveland, from which point he and Grandmother could travel. He was desirous of visiting Florida, Colorado, and making one trip to Europe. But Grandmother would have no part of it. She said that “little Dudie” (that was my father Dudley Baldwin Wick) was only one year old, and needed fresh pure milk enroute, not obtainable on such a long tedious journey. Grandfather told her, and I quote from his diary, “Tut, tut Mary, I have taken care of that. We will simply hitch our family cow on the rear of our carriage train; whenever Dudie needs nourishment, we will halt and milk the cow and what could be fresher than milk right from the Bossie Cow?” This convinced Grandmother, and they moved their furniture in a train of wagons and carriages over the difficult terrain in 1847 to Cleveland.

My great, great, great, great, great grandfather, George Steele, left England and arrived in Massachusetts in 1620. His will is in part of the Hartford Probate Records of the year 1663. The Reverend Stephen Steele was born in 1696, died in 1759. He graduated from Yale in 1718 when the college was only 17 years old. His grandson, Zadock Steele, was born in 1758 in Randolph, Vermont. He was captured by the Algonquin Indians and carried to Canada. The book entitled “Captivity and Suffering of Zadock Steele” chronicles his escape after two years of brutal treatment, and his heroic return to Vermont. His son, Horace Steele, Sr., born in 1791 in Vermont, traveled west to Cleveland and established the Cleveland Times, the first seven column newspaper in Ohio. He was the editor and publisher of the paper which continued publication until the Mexican War. To this day, preserved copies of the newspaper reveal the paper to be snow white, having never yellowed with age, as it was made with cotton. Horace Steele eventually moved to Painesville, Ohio where he died in 1864 at the age of 73.

His son, my grandfather, the Honorable Horace Steele, Jr., was four times mayor of Painesville and president of the Citizens Bank. Grandfather built on the south side of the park the largest brick three-story house in Lake County. It featured the first three indoor bathrooms in the county. There was a faucet for rain-water in all three bathrooms. My grandfather had a tank built on the roof to catch the rain-water which was piped through his baronial house. The mansion had a ballroom on the third floor and the rooms of the house were decorated with imported wallpaper. Landscaped with beautiful flowering gardens, the family home was a showplace. He contributed the bandstand in the center of the town park where, as a boy, I enjoyed the Regiment Band Concerts on Friday nights.

My Grandfather, Henry Wick, Jr., having made his move to Cleveland in 1847, began to put down roots.

Grandfather Wick’s home was a yellow frame house, set back on a deep lawn on the northeast corner of Superior Avenue and Bond Street (now East Sixth Street, the present site of the Federal Reserve Bank). My father attended the Rockwell Street School, which is now the site of the Cleveland Board of Education Building. Father later attended the private Punderson School. His education continued at Oberlin Academy.

This was the time of the Civil War and Father was too young to enlist in the Army, so he joined as a Drummer Boy. Grandfather was very unhappy about this, because he felt his son was too young to be off to war. Grandfather was a personal friend of War Governor Todd who had Father, in the troops, picked up and brought back to Cleveland. But he implored his parents to let him re-enlist, for he reasoned it would be difficult to study when all his friends were away in the Union Army. So Father joined the Company D in 150th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He was in the Army of the Potomac, in defense of Washington. He was later transferred to the Light Artillery, from which he was honorably discharged at the close of the Civil War by President Abraham Lincoln. His name is inscribed on the north wall of the Soldiers and Sailors Civil War Monument on Public Square.

Upon his return to Cleveland, Father went to work in the Wick Bank and took all his meals with the family. Father had to return to the bank each night and sleep on a cot in front of the safe door with a shotgun, for Grandfather keenly felt the great responsibility for the safety of official and private funds on deposit in his bank. Father continued with that nightly responsibility until he married my mother on July 28, 1875. Grandfather then employed a night guard to protect the bank’s safe so Father could live with his wife, as Grandfather was very fond of my mother.

Henry Wick, Jr., had each of his three sons, Alfred, Dudley, and Harry, work for him in his Wick Bank. They all worked diligently for their father who was a serious task-master. The result was that he promoted his middle son Dudley to Executive Vice President, with the wish that he succeed him as President of the bank. Alfred then resigned, and he developed the Cleveland Bank Clearing House. Henry resigned and took his family to Europe, and put his two sons, Henry and Kenneth in school in Switzerland. Dudley Baldwin Wick, my father, became president of the Wick Banking and Trust Co. in 1895.

My grandfather’s great grandchildren born in Cleveland are: Mrs. Howard P. Eells, Jr.; Mrs. Walter Halle; Mr. Corning Chisholm; Mr. Robert B. Wick; Mr. Douglas Wick; Mr. William Wick (all brothers); and their cousin, Mr. George Chandler Wick and the Reverend Calhoun Warren Wick, as well as the late Warren H. Corning and the late Kenneth Bryant Wick.

Meanwhile my mother, Emma Steele, spent her girlhood in the pleasant world of Painesville, Ohio, devoting much time to her musical interests. Her great talent carried through her lifetime of activities in the musical arts, and her love of music has been my personal inspiration over my long life. As a girl, Mother was taking piano and organ lessons from a talented local musician, the organist of St. James Episcopal Church in Painesville. When this capable lady died, the Rector requested that Emma Steele, then only fourteen years old, be allowed to play the organ until the search committee could secure a permanent organist. Grandfather agreed to the arrangement but insisted that no salary be paid to his daughter. The entire congregation said: “Seek no further; we want Emma!” When she turned 18, the congregation surprised her with a gold watch, suitably engraved to honor her.

The romance between Mother and Father was sparked during one of the many social events that linked Painesville, Youngstown and Cleveland in those early days. While my mother’s interest was in scales, my father’s keen interest was in sails. He was a part-owner of the famous yacht, “The Phantom”, his other partners being’Mr. Harvey H. Brown and Mr. Charles Sheffield. These three young men sailed throughout the Great Lakes on their wonderful yacht. They took depth soundings (the first ever made) in Georgian Bay. When sailing in Lake Superior, Mr. Brown said the cool water chilled the champagne to just the right temperature. On one such excursion on Lake Superior, catastrophe almost overtook them. The 1873 headline in the Detroit Free Press proclaimed: “Great fear for lives of three prominent Clevelanders .. . five days overdue for arrival.” The melodrama ended with their safe arrival after having endured severe storms, proving the extra sea-worthy qualities of “The Phantom” and the sailing abilities of Brown, Sheffield and Wick.

In the spirit of romance, two days before my parents were to be married, Father’s partners, Brown and Sheffield, gave a yachting party for the large bridal entourage.

The “Phantom” was entirely dependent on wind to navigate; it had no auxiliary engine to assist the boat on calm days. The yacht was becalmed out in Lake Erie, marooning the group. The parents of the bridal party all waited anxiously at Fairport Harbor for the wind to come up; eventually the boat sailed back to shore for a delayed dinner party.

This exasperating experience caused Mother to dislike sailing, so Father sold his one-third interest in the “Phantom” to his partners. After a wedding trip to Niagara Falls and up the Saguenay River, they went to Montreal, where Mother was invited to play the huge organ in the Catholic Cathedral. Her performance so pleased the Bishop that he had the cabinets unlocked to show the rare jewels and elaborate vestments.

Upon her arrival in Cleveland, Mother was asked to be the organist at the Old Stone Church; she was only twenty-one years old. Grandfather Wick had had the same pew at Old Stone Church for 48 years. When my parents were married in 1875, Father was already singing in the church quartet. As was typical of Presbyterian churches, Old Stone had a quartet. The soprano was my aunt Helen Corning; contralto, my aunt Florence Chambers; baritone, my father; and second bass, my uncle Dexter Chambers. When my mother became the organist it was an unusual musical family affair.

Five years later, Mother was more interested in her own Episcopal church, Trinity Cathedral, where she was persuaded to become their organist. Mother was the organist at Trinity Cathedral for 27 years. Father transferred his membership there so that our family could all attend the same church.

The two stained glass windows in the southwest corner of the Cathedral tower over the organ are in her memory. A bronze plaque near the organ states: “In memorium to Emma Steele Wick, organist.”

She was also a talented pianist and one of the founders of the Fortnightly Musical Club, where she performed as soloist in their first recital. In the music room of our Euclid Avenue home, she had two Steinway grand pianos for playing two-piano duets. She also had a small pipe organ.

When Charles W. Bingham married Molly Payne she requested that my mother preside at the organ. Molly was a little late for her wedding and my mother filled in the time by playing all the popular music of that period for that large assemblage at the Old Stone Church. She played so inspiringly that many husbands said they had to restrain themselves from dancing in the aisles with their wives!

My mother’s boundless love of music and her lifelong participation in musical activities was a key ingredient in my life. My irrepressible urge to sing and dance, even to this day, is a tribute to my mother.

By the time my parents were ready to set up housekeeping, Grandfather Wick had established a veritable compound of houses to accommodate all his children! He was a very devoted family man, and in order to have all of his married children living around him, he bought a large tract of land on Superior Avenue, bounded on the north by St. Clair, on the south by Payne Avenue and on the east by Dodge Street (now Seventeenth Street). He built for himself a large stone house and stable. Adjoining large lots were given by Grandfather to each of his three daughters and three sons as their wedding presents.

My father’s house was opposite Grandfather’s -a large double brick and stone trimmed residence with a ballroom on the third floor. Next door to my father’s house was Aunty Florence and Uncle Dexter Chambers; next was Aunt Mary and Uncle Alfred Wick; next Aunt Helen and Uncle Warren H. Corning and lastly, Aunt Florence and Uncle Henry Clarence Wick.

It was in this fine house on Superior Avenue, in the bosom of the whole family, that I was born on November 23, 1885. It was an ideal environment for the first ten years of my childhood. We were a close-knit clan, with Grandfather Wick as the great Patriarch of the family. All of us were expected to visit our grandparents every Sunday afternoon. They were very strict Presbyterians -Grandfather was an active Elder of the Old Stone Church on Public Square. During our Sunday visits, we grandchildren were forbidden even to build castles with playing cards or use checkers or chess. But we were invited to feast on Sagertown Ginger Ale, cookies and cake.

Daily life on Superior was punctuated by the arrival of various tradesmen and purveyors of goods. The Milk Man came with his many 50 gallon galvanized milk cans, and with a long dipper transferred the milk to a ten-gallon can, delivering it to our kitchen, The Fish Man heralded the arrival of his cart with blasts on his shrill fish horn. One of my favorite peddlars was the Waffleman. He made the waffles right on his horse-drawn wagon, sprinkling them generously with powdered sugar. When he rang his bell all the children came running. It was always interesting to watch the Scissors Man, with his cartful of equipment for sharpening knives and other tools. The Ice Wagon would arrive several times each week and the driver would carry in the large 100 or 200 pound cakes of ice to fill the ice boxes. While he was busy, we had time to scoop up smaller slivers of the ice to munch on. I liked best the Organ Grinder with the little monkey dressed in a bright red cap and jacket, perched on his master’s shoulder. The monkey carried a tin cup which he passed around for pennies.

To attend to our fine team of horses, our cow, our chickens and large vegetable and flower gardens, as well as the big house, we had. a staff of servants. Our cook, waitress and upstairs maid were all faithful girls from Ireland and stayed with us for many years. Bridgette, the cook, married Patrick Quinlan, just over from Ireland; Father found him a job driving the horse-drawn streetcar. In 1890 he was promoted to motorman on the cable cars, eventually changing to the electric trolley when it was introduced. Patrick was never tardy and never missed a day’s work; he always took his wages in an unopened envelope to his wife. With her careful, thrifty management, they were able to see all six of their children graduate from either a college or business school.

By 1890 I was five, and old enough to travel on my roller skates for frequent visits to the nearby Fire Station. Fire Engine Company 14 was located in a brick two story building at the corner of Chestnut Street (Chester) and Murison Street (East Twelfth Street). The firemen slept in white enamel beds on the second floor, living there and cooking their own meals. When the huge brass bell would sound, the firemen would slide down the shiny brass poles to man the fire trucks.

Since the engines were horse-driven, they were backed into position in front of the fire engines (hook, ladder and hose wagons). The harnesses, elevated on pulleys overhead, were released and fell neatly onto the waiting horses.

Occasionally we were lucky enough to witness the real thing and would see the apparatus speed out through double doors, which pulleys and weights opened quickly. All the firemen were friendly and explained all their duties and operations

to me.

Another favorite visit was to Mr. Hooligan, the Blacksmith on Dodge Street (East Seventeenth Street) and St. Clair Avenue. He was a large brawny man with black hair and red cheeks. He wore a black leather apron. I would ride my bicycle down to watch him shoe the horses. The sound of his anvil, the clank of the horseshoes and the red hot fire fascinated me. Sometimes he would fix a broken toy for me. His bellows made sparks fly; he made me stay at the entrance to his shop to avoid being burned.

Another stop on my itinerary was Fitch’s Drug Store at the corner of Payne and Huntington Avenues (East Eighteenth Street). The drug store featured a large soda fountain where we bought delicious chocolate and strawberry ice cream sodas. Phosphates in a choice of flavors were the thirst quenchers.

It was great fun for me to visit my Grandparents Steele in Painesville. I would go there on the Cleveland, Painesville & Eastern Railway or on the Lake Shore, Michigan & Southern Railroad. One day while out in the countryside, I ventured on my bicycle out to “Moody’s Hollow”. A large band of gypsies was camping there. The women in their gay colored long dresses tried to persuade me to come and see the gypsies … trying to kidnap me! I was scared and pedaled my bike faster. Suddenly, gypsy men on horses started to follow me. My bike never sped so fast as I made my safe escape.

Grandfather Steele owned a large tract of land called the Flats, bounding the Chagrin River where the Barnum and Bailey Circus pitched its tents each year. I set my alarm clock for the middle of the night and saw the arrival of three different sections of the circus train. The first section had all the elephants, canvas and poles for The Big Top. The older elephants tested the bridge with their trunks before signaling the younger ones to cross. Those elephants were the power that raised the tall poles to support the canvas for the tents. The raising of the last pole was the signal that breakfast was ready. I remember sitting down with the Aerialists and animal trainers to share a delicious breakfast of cantelope, oatmeal and fried eggs. Since the circus was pitched on Grandfather’s land, I was given a dozen first row seats for the Matinee for my country friends. One of the elephant trainers was named “Sweet Pea”. He was only five feet tall, and very strong in personality as well as odor!

Music was the keynote of our family life and provided much of our entertainment. Mother pleased me by taking me to Gray’s Armory every year to hear the Sousa Band. I wanted to become a good cornetist and dreamed of taking John Phillip Sousa’s place as a conductor.

In the fall of 1895 I teased my parents endlessly for a cornet. Dad said that if I completed a quantity of addition, multiplication and short division problems he believed that Santa Claus would reward me next Christmas. Under our Christmas tree I found a fine, solid brass cornet in its leather case. Although Mother played the harp, piano and Trinity Cathedral organ and Father played the guitar, cello and flute, neither could help me to blow a brass wind instrument! So all Christmas Day I blew hard, striving to play a tune.

The next day I suffered with severe double earaches. Our family doctor, Hamilton F. Biggar, came and pronounced that over-straining had produced ruptured abscesses in each ear. The condition was excruciating and Father often tried to ease the pain by blowing hot smoke from his pipe into my ears.

Although I suffered for five months, I still persisted in my desire to learn to play the cornet. Eventually I was allowed to take lessons from Mr. William Barnes, a famous cornetist in our Lyceum Theatre Orchestra, who taught me how to properly ‘lip and blow’. My first piece was “Nearer My God To Thee.”

Once in a while as a young boy I would glimpse the less fortunate world around me and realize that everyone’s life was not like mine. There were many drunkards on the streets and on the streetcars. There were some beggars and all kinds of cripples. Some with just one leg, some without any legs, pulling themselves along in crude carts. There were poor people who looked cold in the winter in threadbare clothes. Summer was cruel to others: the Irish road gangs sweating in the summertime as they swung their axes and poured hot tar on the roads. There was no road machinery at that time to take the weight off their arms and shoulders.

Mother would let me go with her at Thanksgiving and Christmas to carry heavy baskets of holiday food and I saw where the poor lived in cold barren rooms filled with children. Many unfortunate souls were spared from hunger by going around back to the kitchens of the big houses . .. usually it was an Irish cook who gave them hot coffee and food.

People of wealth often gave charity balls to raise money for the poor.

While I was busy with my childhood adventures, my father was busy carrying on the tradition of the Wick family bank, which had been started when Grandfather Wick made his move to Cleveland way back in 1847.

Grandfather, having brought his family here, at the urging of his brother, Lemuel, found Cleveland to be quite a developed town, with its population of almost 14,000 and its modern gas-lighted streets! Grandfather was a young man at that time but had been working hard since boyhood and thus made a favorable impression on two prominent citizens who became his partners in establishing the private banking firm of Wick, Otis and Brownell.

The Honorable A. C. Brownell was a prominent older man who went on to become Mayor of Cleveland from 1852 to 1854. Brownell Street was named for him. Mr. William A. Otis went on to build the Otis Iron Works, which became Otis Steel and merged into the Republic Steel Corporation.

By 1853 Grandfather had bought out his partners’ interests and changed the name of his firm to Henry Wick & Company, private bankers. The bank was located next to the Weddell House; it was a three-story brick building on the corner of St. Clair Avenue and Bank Street (now West Sixth Street). The Weddell House was famous because Lincoln had stayed there and made an historic speech from its open balcony.

For over 40 years the Henry Wick Bank continued until it was incorporated as the Wick Banking & Trust Company under the state law in 1891. My father, having begun his banking career sleeping on the cot guarding the safe at night, became a familiar face in the quiet, industrious atmosphere of the bank. Daily the gray-bearded Henry Wick or the polite younger Wicks welcomed each client to the family establishment, making it an inviting place.

This was before the advent of modern office equipment and many tasks were accomplished through human ingenuity rather than technology! Grandfather could add three columns of figures at a time; many other bankers had learned to do this same difficult addition for want of a better method. Type· writers and Xerox copiers were unknown. The bank’s correspondence was written in longhand, and to make duplicates, an ingenious press was used. It was made of iron with an iron wheel on top that turned clockwise to increase the pressure. A sheet of wet canvas was put over a sheet of yellow tissue paper which, in turn, was put over the letter to be copied. The book of yellow paper was kept next to the press and contained copies of the correspondence. I still have some sheets of the yellow tissue copies from my grandfather’s bank correspondence.

In 1882, my grandfather, commissioned my father to build the Wick Building on the Public Square, immediately west of the Old Stone Church. The original plan was to have the Wick Bank occupy the first floor, with offices on the upper six floors. But Father was deluged with requests to include a theater in the building complex. The only facility for concerts and theatrical productions at that time was on the second floor of the old Academy of Music on Bank Street (West Sixth Street near Superior). The Board of Trade and other civic groups had condemned the Academy as a fire-trap.

Grandfather, being a strict Presbyterian, at first would have no part in creating a theater, which was considered wicked by his Old Stone Church. But he finally consented to contribute to the progress of the city, and the plans were changed to accomodate the much desired theater.

The Wick Building was completed in 1883, built of brick and trimmed with stone; it was considered beautiful architecture and was a welcome improvement for the Public Square. The Park Theatre was located in the central part of the new three story edifice and gave to Cleveland a large modern playhouse.

In addition to the large orchestra circle and main floor, it had a balcony and a third floor gallery.

The Park Theatre was managed by Augustus F. Hartz. “Gus” Hartz was one of the best known theatrical figures in the city’s history. Born in Liverpool, England, in 1843, he was apprenticed to a stage magician at the age of eight and studied with a tutor in the evenings. He followed a stage career until 1880.

The opening night of this grand theater was described in the Cleveland Plain Dealer as follows:

“The Park Theatre opened October 22, 1883, with one of Sheridan’s comedies, and the evening was a brilliant social event. The opening night of the theater saw the ‘School for Scandal’, a comedy which had opened the Academy of Music about thirty years before. Mlle. Rhea was Lady Teazle. A reception for Mlle. Rhea was held at the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Dudley B. Wick, 660 Superior Street, following the premiere performance.”

But the splendor of this new cultural center was short-lived. Less than three months after that beautiful opening night, disaster struck. The following detailed account of the tragedy is quoted from the Plain Dealer, as recounted by S. J. Kelley in part of a series of nostalgic articles written in 1941:

“On the icy Saturday morning of Jan. 5, 1884, the Park Theater burned. The first alarm sounded at 8:30 and Engine No.1 was the first to respond from its station a block away on St. Clair Street. Fire bells rang throughout the city and Engines No. 2, 3 and 4 soon were on the scene with hook and ladder companies.

Smoke poured from the Wick Block and theater at the northwest corner of the Square.

Court Place ran along the west side of the building. Across the alley was the old Court House. Directly east was the Old Stone Church. In six minutes, four steamers were playing on the fire. Lines were run through the alley to the the stage entrance and in the small front lobby on the east side. Firemen were driven from the stage by burning scenery, while those entering the lobby groped their way into blinding smoke from the auditorium.

Seven more steamers responded, some of the horses galloping three miles in a temperature 4 degrees above zero. Eleven engines were soon working, either on the Square or on Frankfort, St. Clair or Ontario Streets. Flame burst through the skylight above the stage. The west tower of Old Stone Church caught fire and the intense heat set the roof on fire. Soon arches and interior woodwork were ablaze, despite the pumping of three engines.

In less than two and a half hours the theater was destroyed. Only its main blackened walls were left. Some front offices were saved, but the floors were flooded with ice. I remember seeing the toppling cornice, the crashed plate-glass windows and icicles hanging from the front. The west tower of the Old Stone Church was windowless and black and the whole structure was a ruin.

But 3 months had elapsed since the opening of the Park during which the Hess Opera Company appeared in grand opera, followed by ‘The Black Crook,’ ‘Siberia,’ ‘The Squire,’ ‘The Silver King;’ Denman Thompson in ‘Joshua Whitcomb,’ and Margaret Mather. The Friday night before the fire, the George H. Adams Company played ‘Humpty Dumpty.’ Rumors circulated that it was caused by incendiarism and Janitor Wood told of a strange experience early Saturday morning. At a meeting held a day or two later at Engine House No. 1, to investigate the fire at which Manager A. F. Hartz, Chief Dickinson, Dudley Wick, Architect Koehler and Contractor Moran were present, he related a weird story.

‘I arrived at the theater about 7 o’clock, went back under the stage, changed my clothes and took a broom, duster and pail used in cleaning. The two girl assistants had not arrived. I swept the front hall and theater and went back to the stage. Properties used by the Humpty Dumpty Company lay about. I went under the stage but could smell no gas and after warming myself, came up and lit one jet on the wall toward the church. It sputtered and I watched it until the air escaped. In passing the basement meter room, I noticed no gas jet burning. By the stage clock it lacked one minute of 8:30.

‘A moment after the gas was lighted, I heard an explosion and was knocked down. I arose and saw a ball of fire flying toward me. It was about six inches in diameter with black streaks running through it. It looked like a large wad of burning paper. When about four feet from me it exploded and I was knocked down again. The stage was littered with burning substance that looked like paper. I got up and was knocked down by a similar ball. Then I saw six or eight balls of fire coming from a corner and going over my head. I heard a roar, ran down the cellar stairs and saw sticks of fire whirling. When these went out, they were followed by others that roared loudly. Then the whole place seemed afire and I rushed out. helping one of the girls who had come while I was at work.’

The fiery ball story created quite a sensation, as Wood insisted that it actually occurred.

The first Wick Block was valued at over $100,000. Henry Wick a few days before had placed a safe on the ground floor next to the Court House. When it was opened valuable papers and $5,000 in currency were found intact. In two and a half months Park Theater receipts amounted to $45,000.”

The cause of the great fire was presumed to be a gas explosion. Since the stage footlights , ceiling chandeliers and side wall lighting fixtures of the theater all used gas, it was concluded that gas had escaped and caused the explosion that resulted in the destruction of the Park Theatre. Only the walls of the new Wick Block remained, sheathed in icy desolation.

The Old Stone Church, immediately adjoining, was badly damaged. There was agitation by some members wanting the Church to move to a residential section. Others, led by John A. Foote and Colonel John Hay, succeeded in preserving the historic site, and plans were made for restoration of the interior. Charles F. Schweinfurth was commissioned to do the job. He designed the fine open-timber ceiling; the wall decorations were executed by his brother, Jules. Although the lofty steeple survived the disaster, it was later declared unsafe and taken down from the east tower, which was ornamentally finished through a gift from Mrs. Samuel Mather.

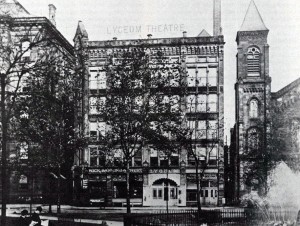

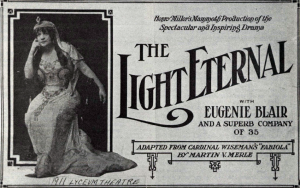

The Wick Building was promptly rebuilt. The new building was twice as large as its predecessor. The new six story building of brick and stone trim was considered an architectural gem. The new Lyceum Theatre was even more elaborate than the Park. Every detail was the best available at that time; truly luxurious for theater appointments of the day. To quote from the Cleveland Leader and Plain Dealer, the opening night of the Lyceum Theatre is recorded:

… “At the opening last night, September 2, 1889, of the beautiful new Lyceum Theatre, there was life and praise and animation. It gives to Cleveland the most modern playhouse in America.”

An important innovation was the use of electricity for illumination. The audience was excited and thrilled by the dazzling display; the newspapers marveled at the use of electricity and wrote about it in detail.

“The row of electric lights way up near the roof sparkled brilliantly, like so many gigantic diamonds. The auditorium proper is illuminated, as is the vestibule and foyer, with the incandescent electric light which presents a brilliant and exceedingly elegant appearance. These beautiful electric lights are produced by two three-hundred watt BRUSH dynamos. The large chandelier in the center has one hundred electric lights to illuminate the auditorium below, and several upturned arms are provided with gas burners to be used in case of possible trouble with the electric light. The great center ball of polished brass is ornamented with jewels of many colors that reflect brilliantly when illuminated …

“The opening attraction was W. J. Scanlon, a star who has risen high in the world since he appeared in Cleveland five years ago at the dingy old Academy of Music in 1884. Scanlon has a pair of sparkly, roguish eyes and a smile that captivates the feminine wing of the audience. The story is one of love and villainy and is well told, and what is better still -by a company which is far above the average. . .”

The new Lyceum Theatre boasted a unique feature: the West Box on the main floor. This was known as the “Wick Box”. It was never sold, and contained up to ten seats, reserved exclusively for the Wick families and their guests. My father kept a record on his desk at the bank, assigning names and numbers of seats as requested for the different performances.

Each of the theatrical productions played for one week, including two matinees, Wednesday and Saturday afternoons. It became the custom for Mr. and Mrs. Dudley Baldwin Wick to have the Box on Monday evenings for the opening performance of each new show, which they often preceded with a theater dinner party or after-performance entertaining.

Grandfather had relented to allow the theater to be built, rationalizing this as a contribution to civic progress. Being such a strict Presbyterian, however, he resolved that he would personally never enter it. But, hearing so many praises, and seeing the favorable write-ups in the newspapers, he finally said to my father: “Dudley, Mother and I next Wednesday matinee will have our carriage take us to the stage door on Court Lane (which led directly to the Wick Box) and just get a quick glimpse of what a theater looks like … but not stay.”

However, they were both so enchanted they enjoyed the entire performance, and they never missed a matinee as long as they lived. Most of the plays were fine drama, but occasionally a musical with chorus girls and dance routines played; these were Grandfather’s favorites. He often asked Father, “Son, will there be any ‘drilling’ next matinee?”

The Lyceum Theatre was a great feature for me; from the time I was barely four years old I enjoyed it immensely. When I started attending Hathaway Brown School Kindergarten, and all through the primary grades, I would invite my young classmates to join me in the Wick Box at Saturday matinees. By the time I went to University School though, we were all old enough to prefer the Friday or Saturday evening performances, instead. If I invited more friends than were seats in our Box, some would take unsold orchestra seats.

The star dressing room was on the main floor of the stage. I often tapped on the door; a stagehand would stop me: “Little boy, that’s the star’s dressing room -keep away!” But the kindly electrician operating the huge switchboards (after electricity took the place of gas) would say, “That’s okay. He’s Mr. Wick’s son and he knows his way around the theater.”

I recall the first time I got up the courage to visit backstage. The famous black-face minstrel, George W. Primrose, of Primrose and Dockstater fame, had just done his famous soft shoe dance with straw hat, cane, and blazer jacket. I took a deep breath and said, “Gee, please teach me.” So, while he put on more black face and big red lip make-up, he gave me a little lesson. From that moment on, dancing and singing was my greatest pleasure in life. Upon his return the next season, Primrose got a kick out of seeing me imitate him, my having practiced hard all year to master his routine.

I would live for the annual return visits of all the great vaudeville performers -to learn their special secrets. The four Cohans made their yearly visit: George M. Cohan, his father, mother, and sister Josephine. He taught me to clog dance, and to end up with a cartwheel or a back flip or handspring.

Fred Stone was the great exponent of the waltz clog. In the “Red Mill” he sang, “In Old New York”, taking the role of a hand-organ grinder with a live monkey, dancing to that waltz-time tune. He told me for the waltz clog not to take my taps vertical, but circular, to better swing into waltz tempo. Then Pat Rooney taught me the Irish Jig routines to the tune “Rosy O’Grady,” which he immortalized.

I was lucky; I certainly picked the four greatest masters of dance as my tutors. They so encouraged me that I’ve been happy to do song and dance numbers all my life for charities, hospital fund raisings, and over 25 Yale Alumni Musical shows.