Main Body

Millionaires’ Row: Mischief

The formality in our lifestyle did not preclude the fun in our lifestyle! Some of my most vivid memories are of the ways in which we amused ourselves, indoors and outdoors.

As children living in those huge mansions, we found ways to utilize those grand facilities for our own purposes. For example, our third floor ballroom with its hardwood floors was ideal for roller skating. My friends thoroughly enjoyed my private roller rink. That ballroom also made a perfect setting for my elaborate train set. For Christmas I had received a railroad train pulled by a replica steam locomotive, which was fueled with alcohol. It traveled on wide-gauge tracks (wider than today’s Lionels) through tunnels and over bridges, giving off its loud steam whistle. Many a rainy day my boyfriends shared in those imaginary voyages on our third floor.

The most unusual third floor on Millionaires’ Row was to be found in the Stewart Chisholm mansion. My close friend Douglas Chisholm, the son, had converted the far end of the ballroom into a full-scale theater. There was a stage with full curtain under the proscenium arch; there were two full sets of scenery: one a livingroom, and the other a country meadow with a well-painted mountain in the background. We children used our imagination and put on shows we thought well worth the penny admission. The servants were our most loyal audience when our parents could not always attend.

The reason most of the big houses had ballrooms, of course, was not for the amusement of the children -but for the adult dancing parties. There would be a raised platform where the orchestra would sit and play into the wee hours. There would also be a pianola, with its raucous, twangy sound, in marked contrast to the sweet music box.

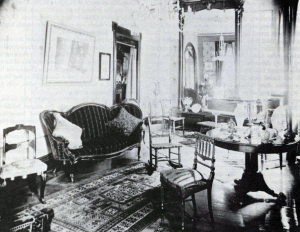

Music boxes from Germany and Austria were very popular at this time. They were large, oblong mahogany boxes, simple in design and very handsome. Some of the very large music boxes cost as much as $1,500 to $2,000. They had glass tops, exposing the shining brass mechanisms which were able to play only a few pieces in faint, tinkling sound. Of course, there were smaller music boxes which were usually kept in the parlor for our daily amusement.

When the phonograph became popular, the market for the large music boxes ceased. The phonograph could reproduce the sounds of an entire orchestra of 60 or more parts, and with much better effects. The Grafonola was one of the early forms of this new instrument, using cylinders before the flat records were introduced. We had a Grafonola in our library. It was enclosed in a handsome mahogany table, with the playing mechanism under a top panel.

Next came the Victor Phonograph, with its big horn and famous white dog trademark. The elegant model of the Victrola came in a tall mahogany cabinet. Sometimes the old needles made Caruso, Tetrazini and other great Metropolitan opera stars sound a bit raspy.

Music, in its many forms, delighted us. At every party there would be at least one person who could play the piano, and often the guests would stand around the piano and sing. As the evening progressed the rug would be turned back, and there would be dancing.

The young people loved to dance. One Christmas vacation I was asked by a friend to come over to her house in the middle of the morning and stay for luncheon. After all the guests arrived, we turned back the rug so we could dance. To make the floor slippery, we shaved off the end of a candle and waxed the floor. We then had to find somebody to play the piano for us. Our hostess said she hadn’t touched the piano for 20 years, but she did remember just one song, “If a Body Meets a Body Coming Through the Rye.” My friends danced the two-step to the only piece she knew and we all had a wonderful time.

There were some very musical families who would add a few neighbors to their ensemble and give a recital. The music teachers scheduled one or two recitals a year for their pupils. At almost every recital there was sure to be a young person playing a violin. His selection would invariably be “Humoresque”.

Another favorite meeting place was the pantry; my young friends and I would gather in one of our pantries for a taffy pull. This ritual would take over an hour, with several boys on each end pulling hard. Then the cook would cut the taffy in small pieces for us, because the hard candy had to be severed with a sharp knife. Then came the fun of eating it. The girls loved making fudge. So, the girls gave the boys fudge and the boys gave the girls taffy.

The outdoors offered a different set of amusements. Croquet was a popular game on Millionaires’ Row. There were lively games between the Prospect Croquet group and our Euclid Croquet group. Our matches were played at the Eells’ house on Prospect, and our house on Euclid. The large flat expanses of lawn were ideal for setting up the wickets. Very often, after Sunday dinner, my parents would play croquet with their guests. The men in their cutaways and the women in their floppy hats and long skirts made it a formal game.

Winter meant sleigh races! Euclid Avenue was closed at East Twenty-Second Street, and at the eastern end at East Fortieth Street. On Saturdays and Sundays many expert horsemen drove their own sleighs. Mr. Charles A. Otis, John Sherwin, J. B. Perkins, Harry K. Devereux and Colonel William Edwards could often be seen. Among the famous horsemen racing with the sleighs was James H. Hoyt. Mr. Hoyt also liked to drive four-in-hand, and his two famous teams of horses were Fuss and Feathers, Brick and Mortar. People came from as far away as Painesville and Elyria to witness these exciting races by such expert horsemen. Those of us who lived on Euclid Avenue would give sleigh racing parties, inviting guests to witness the events. Of course, we went sleigh riding without the excitement of the races, too. I remember riding in the horse-drawn sleigh along Euclid Avenue, snug under a fur lap robe, my feet warmed by flat stones that had been heated.

Gordon Park was at the lakefront where Rockefeller Boulevard entered. Those were the days when Lake Erie was pure and this was a popular swimming spot. The ride along Rockefeller Boulevard to reach Gordon Park and the lake was enhanced by the beauty of Doan Creek, which bordered the Boulevard all the way. The bank on the west side was steep, and made an ideal place in winter to go down on sleds. I remember my University School classmates, Clark and Hamilton Bole, who lived at the corner of Superior and Ansel Roads. Their house sat high on a hillside overlooking Rockefeller Boulevard; an ideal hill to coast down. There was so little traffic of horses and carriages driving by, we could glide on our sleds right across the Boulevard up to the edge of Doan Creek.

The ornate stonework tunnel bridges punctuating Rockefeller Boulevard at Wade Park, Superior and St. Clair Avenues, were designed by Charles Schweinfurth. Driving through the tunnels was fun because of the echoes of the horses’ hooves.

Wade Park consisted of fertile farm lands given as a gift to the city by the Wade family. The bubbling, clear Doan Creek ran the length of the park. One could reach the park via the Cable Railway which started at West Ninth Street and terminated at the eastern end of Hough Avenue, formerly known as Cable Park. Row boats were rented on the small lake, later called Rockefeller’s Lagoon.

The new zoo in Wade Park had its small beginning in 1889, with two black bears, two catamounts (wild cats), a family of crows, a pair of foxes, and a colony of prairie dogs. The next year the Octagon House was completed. This housed the birds, tropical animals and the monkeys, who particularly fascinated me. It was fun to watch these interesting creatures entertain the visitors who fed them peanuts. Mischievous boys gave the monkeys chewing gum, then watched them try to manipulate it. A herd of American deer was given to the zoo by Jeptha H. Wade in 1890, just before he died. This zoo was located in the general area now occupied by the Garden Center.

On the lower drive (now a ravine) there was a spring famous for its delicious cold water. My parents, and also my Grandmother Wick, made frequent trips there in horse-drawn carriages to fill containers to take home. When I was about five years old, I was eager to accompany them not only for the spring water, but for the chance to visit the two black bears in their caged homes. When I was a little older, my friends and I enjoyed riding our bikes to revisit the spring and the bears.

Wade Park was very popular as a recreation spot. A music pavillion was the site of band concerts and entertainments. Rowboats could be rented reasonably on the tranquil lagoon. In winter, we all enjoyed ice skating there. On Saturdays, there were championship high-speed skating races. The popular skate for this fast skating was the old Donahue skate blade -a long blade mounted on a mahogany base.

There were two plank roads: one running east of 105th Street, and the other running out Mayfield Road from Coventry to Brainard. These were controlled with toll booths and well maintained. Often young people would go out driving in a surrey with the fringe on top, the horses clop-clopping along those planks. There were excursions to Luna Park and Euclid Beach Park with the excitement of daring rides and live entertainment.

For those who preferred to stay at home, there was the viewing of stereoscopic pictures through special lenses magic lantern shows -or sitting close to a loved one in the swing on the front porch. Sometimes the chains that held the swing riveted to the roof would squeak and make even louder noises than the beating of one’s heart.

Even being alone could be gratifying, especially if you were a stamp collector. In 1876 a Philatelic Association was formed in Cleveland, making it one of the oldest such organizations in the world. Mr. George Worthington hired a man to look after his stamp collection, built up to value over a million dollars. His was the second largest collection in the world at the time. The portraits of President James A. Garfield and Oliver H. Perry appeared on five-cent and ninety-cent postage stamps.

I remember the annual Police Parade. The men marched in military formations while their bands played spirited marches by Sousa. Chief Kohler, a tall, extremely handsome man, was the center of attention on these occasions. Political campaigns were often enlivened with parades, too. In order to involve laborers and common folk, the parades were usually staged at night, with torch light processions. Each participant carried a tin kerosene lamp which glowed, illuminating the procession as it moved along.

Then there was League Park: the stadium and coliseum of my childhood. The ‘ball park’, as it was sometimes called, was located on Lexington Avenue at the corner of what is now East Sixty-Fifth Street. It opened on May 1, 1891 and was the home of the American League’s Cleveland team before they were named the “Indians”, in 1915.

University School was in the neighborhood of the park, so we boys used to enjoy attending all the games. The Plain Dealer, April 29, 1903 said, “Cleveland has gone baseball-mad .. . actually raving mad. Yesterday was no holiday, but nearly 20,000 wedged their way into League Park.”

Tris Speaker became manager in 1919 following Lajoie. Tris Speaker’s Indians won the American League pennant on October 2, 1920. Amateur Baseball Day was celebrated by the participation of the three greatest ball players of all time: Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker. Pictures of the baseball players were printed on cards with their scores and athletic records. We boys collected them and traded our duplicates.

Football was also popular at League Park. For many years, I joined the annual prilgrimage on Thanksgiving morning to see the two rival college teams, Case School of Applied Science and Adelbert College, compete. League Park would be filled for this event; then all would go home after the game for Thanksgiving dinner.

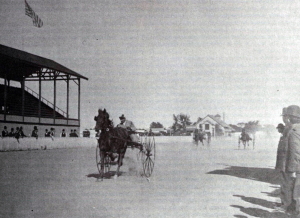

The Glenville Race Track was an elegant facility, with its large steel grandstands, protected from the weather, hosting many of the great events in horse racing. In 1885 Maud S., “Queen of the Turf’, broke the trotting record for the one·mile here at the Glenville Race Track. She formerly belonged to William H. Vanderbilt. I used to think Maud S.’s famous golden horseshoe that hung at the entrance was indeed a great honor for any horse.

Many Clevelanders who had wonderful fast horses drove their own harness racing rigs on this track. Charles A. Otis, James H. Hoyt, etc. Each year an annual race was held. I have one of the badges from the race week of 1897 in my button collection. All summer there were races every Saturday afternoon. This famous one-mile track was also used for four-in-hand contests. Those who drove their four-in-hands with the greatest skill, handling their horses, would get the blue ribbon. The four-in-hand horses pulled interesting carriages called “tallyho’s”. Each carriage always had a footman who acted as trumpeter, playing the very long brass horn. The lower part of the carriages were closed; the parallel seats high up atop carrying the drivers and extra guests.

In addition to horse racing, this wonderful track was used later for many other spectator events. The bicycle races, the auto races -I will tell you all about them in a little while. The Glenville Race Track was finally abandoned in 1908 when Fred H. Goff, the mayor of Glenville, declared the betting illegal.

The preoccupation with horses was not confined to the racing. The first horse shows were held at the Chagrin Valley Hunt Club, and polo was introduced about the same time. Polo is played by four men on a team; the players on the first polo team were Corliss Sullivan, E. S. Burke, Jr., Lawrence Hitchcock and A. D. Baldwin. This became a winning team around the state.

Polo was like a croquet game, with the riders swinging long mallets endeavoring to hit the ball while their horses rode by in full gallop. Unlike the courteous style of croquet, however, here players shouted swear-words when they missed the ball. It was a fast and dangerous sport. I saw Dave Ingalls thrown off his polo pony, and was worried when I heard he had been rushed to the hospital.

Polo was also an extremely expensive sport, as the polo players had to own a string of polo ponies. The ponies could not be used two days in a row in the matches, needing to be rested after such grueling speed and endurance demanded of them. Mr. Edmunson S. Burke, Jr. owned a string of well-trained and valuable Mexican ponies. They helped him win many a polo match. Mr. Walter C. White housed his valuable ponies in stalls with running water.

Mike White, the uncle of Tom Vail, the newspaper publisher, invited us for cocktails after a polo match. I was surprised when he greeted us wearing a polo coat. He had not had time to shower and change his clothes. To keep himself from being chilled after such exertion, he was wearing his polo coat. This was the first time I realized that the name of this special tan coat was derived from the game of polo.

The Lennox building stood at the corner of Euclid and East Ninth Street, where the Union Commerce Building is now located. What I remember best about the old Lennox was its large circular display of Civil War battle scenes. Later, it was converted into a roller skating rink. Two-wheel, rubber ball bearing skates were more difficult and challenging to use than regular skates. The skating rink was eventually turned into a bicycle riding academy. Children came there to learn how to ride a bicycle; when they fell off, they were picked up by their instructors. Music was provided and bicycle riders glided along to the rhythm of popular tunes.

On the corner of East Ninth Street, the industrialist and civic leader, Mr. Charles Hickox, built the Hickox Building. In order to make room for this new structure it was necessary to tear down the old First Baptist Church. The historic clock from the church was saved and set in the new 165 foot tower. In 1890, when the Hickox Building was completed, this eight-story edifice was considered a skyscraper and created considerable excitement.

The building had dead white marble walls and, for contrast, colorful mosaic tile floors.

My nephew, Charles Hickox, told me that down deep in the furnace room were two large boilers. His grandfather Hickox had a brass plaque put on each of the boilers. On one was the name of his grandson, Wilson B. Hickox, and on the other was the name of his nephew, Fayette Brown. It was indeed a rare honor to have a boiler named for you when you were a boy.

In 1895, a most unique shop opened on the Public Square (present site of Higbee’s main show window). It sold only popcorn and taffy candy. I was a young boy then, and often walked across the Square from my father’s bank to watch, fascinated, as they made the taffy. The process involved swinging a large bulk of the candy up four or five feet to a heavy foot-long hook on the wall, and pulling it. The throwing was repeated until the taffy was the right consistency to break up into smaller pieces to sell. When Mr. Dudley S. Humphrey started this venture, he was cautioned that it would never succeed.

The public demand for his popcorn and candy proved so great that within two years he owned the whole building! His next venture was the Humphrey Euclid Beach Park, where he continued to sell his famous popcorn and taffy. He built merry-go-rounds, roller coasters, and a large ballroom for dancing, featuring excellent orchestras. He maintained a conservative recreation park, prohibiting alcoholic beverages. Patrons thronged to the park; arriving not only on streetcars, but also via two passenger boats which alternated their departures from their docks at the foot of East Ninth Street. Swimming there in clean Lake Erie was another feature of Euclid Beach.

Another enterprise of Mr. Dudley S. Humphrey was the Elyseum. Located at Euclid Avenue and East 107th Street, near Wade Park, this beautiful indoor ice skating rink was the center of activity for generations of skating enthusiasts. On Saturday mornings, my friends were always there with their dates. Dance music was played and dance programs were filled. The boys and girls glided around the rink, hand in hand.

1896 was the centennial year -the l00th anniversary of the founding of the city of Cleveland. On July 22, 1796, General Moses Cleaveland and his little band of pioneers had sailed from Lake Erie into the Cuyahoga River and had stood upon its eastern bank. The summer of 1896 was gay and exciting for me, filled with celebrations and special treats. I remember the sacred and patriotic selections played on the Trinity Cathedral chimes. A replica of the original log cabin was erected on the Public Square. Parades and band concerts kept everyone excited. I viewed a mammoth, colorfully decorated bicycle parade. The monumental centennial arch was an inspiration to all. The arch was large enough to have horse-drawn street cars drive through it. It was decorated across its top with 30 large colorful flags.

I still have a large collection of souvenir buttons which I gathered in 1896, many of them special mementos of the centennial festivities. One is a round enamel badge with General Cleaveland’s picture on it in a colorful uniform; under his picture reads: “Founder of the City”. Another brass badge, headed “l00th Anniversary”, features an engraved etching of the large two-story log cabin with brick chimneys which was built as a replica of General Cleaveland’s cabin. Another badge engraved in brass is the likeness of the statue of General Cleaveland. There is a bronze button engraved with the likeness of Admiral Oliver Hazard Perry, dated September, 1813, with the inscription, “Perry’s Victory”.

The year 1896 is rich in memorabilia because it was also the presidential election year. William McKinley, running on a gold-standard, sound-money platform, defeated William Jennings Bryan, the free silver candidate. I collected over 75 rare election buttons and emblems, including the G.O.P. elephant with a catch opening up to expose photos of McKinley and Hobart inside. One of my treasures is a McKinley-Hobart button affixed to a small silk American flag, which I received directly from McKinley. I have a copy of the letter I wrote to Governor McKinley, stating that I was organizing a “Boys Club for McKinley” to get our fathers to vote for him. He replied promptly, thanking me and attaching this button to his letter.

This was still not the end of the excitement for 1896. I also attended a giant bicycle show in the Gray’s Armory that year, collecting over 100 buttons and emblems advertising the many fabrications: the Winton bicycle, the White, the Stearns, the chainless gear, Columbia, Cleveland, as well as tire makers and manufacturers of accessories like kerosene lamps.

My button collection also includes the flags of all the nations, the official seals of 48 states, as well as pin up girls from that era of the American theatrical stage. Having acquired all these fascinating mementos, I wanted to mount them in an attractive composite. So, I got on my roller skates and rolled down to Higbee’s store on Public Square. There I found dark blue velvet material measuring five feet by 30 inches. The price for the fabric was $1.25, but I only had taken 87¢ from my piggy bank. The gentle saleslady knew how badly I wanted that material, and said it would be no problem to charge the small balance to my father’s account. I skated home at top speed and mounted the entire collection in neat, even rows on the blue velvet. The fabric is still in perfect condition although that was 83 years ago!

A few of us boys at University School became very close friends and we formed a club called the “SSS”. We certainly never knew what “SSS” stood for, but that was part of the fun. (An older class had a club called “DOD”, and the boys didn’t know what that stood for either.) The members were: Douglas Chisholm, Billy Hale, Prescott Ely, Edward Grasselli and myself. Douglas Chisholm had a marvelous playhouse in the backyard of his family’s mansion and this became our club house. It had high ceilings and a little imitation fireplace and was really a well-built structure. But, it had no light and no heat -so we decided to upgrade our facility. We dug a trench to the Chisholm’s great stone house, and through the cellar window we attached a pipe, connecting it with Mr. Stewart Chisholm’s gas line. Then, needing light, we dug another channel and tapped into his electric line. And Mr. Chisholm used to wonder why his gas and electric bills were going up!

We had a small, four-plate gas burner that we used to cook on. Everything tasted so good that we cooked out there. Having established ourselves in these grand “digs”, we felt our “SSS” Club should have our own independent communication network; after all, it was 1899 and we wanted to be up-to-date. So, we decided on a telegraph system. We each had a telegraph key at home; all we had to figure out was how to set up the telegraph line. There was a series of telephone poles, illuminating poles, half-way between Euclid and Prospect, running back of our barns; and we thought they’d make wonderful poles for us to hitch our telegraph line on. But, how were we to get our line over those trolley wires on East Fortieth without permission?

We set our alarm clocks for about 3:30 in the night. Streetcars did not run at night -they stopped at midnight from Prospect to Euclid. So we knew we were quite safe; we wouldn’t have a trolley car coming by then. We threw a clothesline over the electric trolley wire … and then we intrepid fourteen-year olds climbed the pole on the other side, pulling our wire high above the trolley wires. We were not aware that this was dangerous.

We each had a telegraph key at home and we learned Morse Code so that we could contact each other. If we heard the key clicking we’d know that one of us was calling: “Let’s go out to the club house and have a meeting.” We often telegraphed each other to set up a game of baseball. Tom L. Johnson’s private skating rink was a great feature in those days, so we’d telegraph each other, “Let’s go skating.”

Years later, when Billy Hale, Doug Chisholm and I were all freshmen together at Yale, I happened to remember that telegraph line, and suddenly realized the dangers of it. I quickly called my friends and said, “Do you realize that we’ve got a dangerous situation?! We’ve left in Cleveland a metallic telegraph line that is still up over those trolley wires on East Fortieth Street; and if a heavy wind should come along, or a gale, it could contact the trolley wires and maybe electrocute someone.” We decided that the first thing we would do upon our return for our first Christmas vacation from Yale would be to correct the danger. Again we set our alarm clocks for 3:30 in the middle of the night. We climbed up those poles and pulled that telegraph wire down from over the trolley wires. But we left the rest of the disconnected wire up. It was up for years after that.

In those early days, while we had been busy tapping out messages to each other on our homemade telegraph, our parents would most likely have been out enjoying an evening at the theater. In the late ’90s and the turn-of-the century, there were many more theaters than we have today, enthusiastically supported by the local populace_ A typical listing from the Cleveland Town Topics of the day indicates the variety of live entertainment offered:

“Colonial Matinees: best seats-25¢. Evenings: 15¢, 25¢, 50¢.Euclid Avenue Garden Theatre presents …

Halnorth Garden Theatre, the Star Theatre, the Lyceum Theatre . . .

Gostocks Great Animal Arena, featuring …

Opera House this week .. .

Empire Theatre, Keith Theatre: the best in vaudeville …

Appearing soon: Felix Hughes, Baritone of New York Conservatory of Music . . .

Sousa will play a return engagement in Cleveland …

May 29 and Decoration Day, the 30th: the Glee Club and Mandolin Clubs of Western Reserve University have returned from a short concert tour …

Orpheus Male Quartet will appear in concert . ..”

The Empire Theatre, for high class vaudeville only, opened in 1904 on Huron Road. It was a beautiful theater, patronized by fashionable society. For many years, the Keith Theatre had excellent vaudeville, featuring tap dancing, singing and funny skits. The vaudeville paid 600 or 700 dollars a week to their top billing stars, while a talented actress on the legitimate stage would earn only 29 dollars a week.

Early in the century, there were all kinds of dances performed, named after animals: dances like the grizzly bear, the turkey trot, the bunny hug, and, later, the fox trot. The policy of the Keith circuit kept the vaudeville acts on a high moral plane. The Palace would not allow the turkey trot (which was considered vulgar) danced in its theater.

Euclid Beach had the same policy, and banned not only the turkey trot but all the suggestive dances on their dance floor. The two-step, waltz and the fox trot were all permissible.

I heard a story about several chorus girls who were caught doing the turkey trot in the wings of the theater, taken to the police station and booked for ‘disorderly conduct’. Once there, the girls received a warm welcome from the sergeant on duty. They started singing the turkey trot song and he joined in:

“Everybody’s doing it.

Doing what?

The Turkey Trot.”

Then they did the turkey trot for him. The girls were sent home, free of any charges.

Irene and Vernon Castle came on the scene in 1913. Their dance was so refined and graceful that the vulgar dances like the turkey trot became obsolete. Irene Castle came from a prominent New York family and at 17 became a stage-struck chorus girl, despite her family’s disapproval. Vernon Castle, who was then 23, was dancing in the same chorus. They quickly fell in love and were soon married.

They were a tall, handsome couple and gave private lessons in ballroom dancing to the Rockefellers, the Vanderbilts, and scions of the most exclusive families. It wasn’t long before they were in demand in every part of the country. With such constant traveling there wasn’t time for Irene to have a marcel, so she bobbed her hair, and was the first woman to do it.

The Castles came to Cleveland just before the war to dance at a charity ball. Irene Castle always wore long chiffon dresses and her husband always wore a dress suit. Irene had lovely taste and her own independent fortune. The color of her dresses came straight off the palette of Van Gogh: from shell pink to salmon, from the blue of a mountain lake to the shimmering blue-green of a grotto. When they were dancing, it was as if they were floating on a cloud, her dress whirling around her ankles.

I wish they could have danced through life together. The sad fact is that Vernon was an aviator in World War I, and his plane crashed in burning flames.

Shopping was an important part of our lifestyle from the very beginning. The stores and shops patronized by the residents of Millionaires’ Row stand out in bold relief in my mind’s eye. Several of these early emporiums still thrive, having served generations of the same family. Of course, the locations changed as the center of life moved uptown.

I remember, for instance, Cowell & Hubbard Company first moving from Superior and locating on Euclid and East Sixth Street, and then, joining the trend up the Avenue, moving to Euclid and East Thirteenth Street, where they continue to take pride in the offering of beautiful jewelry.

In 1864, Chandler and Rudd Company opened their grocery store on Euclid Avenue, just east of the present May Company. They later established a restaurant on the second floor. The third floor was reserved for a private lunch club called the Chesire Cheese Club. Its patrons were bankers, attorneys and business executives. Since it was near the bank where I worked from 1912 for three decades, I often ate lunch there. Across Euclid Avenue was another restaurant, DeKlyn’s; very popular for lunch. They were famous caterers for weddings and debutante balls. When Mr. DeKlyn retired, McNally-Doyle took over the fashionable catering operation, which today is overseen by Mr. Robert Pile of the Hough Caterers.

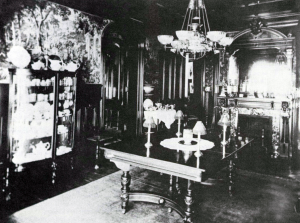

An unusual store was the C. A. Selzer Company, occupying the entire ground floor of the Hickox Building at Euclid Avenue and East Ninth Street. It was heavily stocked with rare china, glassware and chandeliers. Mr. Selzer traveled extensively around the world each year to stock his store with the most priceless inventory. It had an international reputation. Brides treasured gifts that came from Selzer’s. Later generations

inheriting rare china are likely to find it marked on the reverse side, “C. A. Selzer”.

Halle Brothers Company started in 1891, when I was six years old. Mr. Samuel H. Halle and his brother, Mr. Salmon P. Halle, bought the Paddock Fur store on lower Superior and began their successful retail business selling fur hats. An interim move to lower Euclid Avenue preceded the construction of their beautiful department store at Euclid and East Twelfth Street. The store, designed by Henry Bacon, the architect who designed the Lincoln Memorial, opened in 1910. Throngs of people visited the store’s opening and started it on its successful career. The carriage trade was attended by a doorman dressed in a coachman’s livery uniform. Inside the store, customers were welcomed by the attentive floor walkers dressed in cutaways. Customers were greeted personally by the same salespersons, year after year, which added pleasure to shopping.

This attention to detail was a matter of pride in all of the good stores of the day. Higbee’s Department store also had elegant floor walkers in cutaways who greeted the clientele. One morning, a floor walker at Higbee’s objected to a mannikin standing in the aisle. He put his arm around her waist and lifted her up to move her, when he was aghast to find he was holding on to a lady customer. He said, “Pardon me Madam, I thought you were a dummy!”

When Mother went shopping in our carriage, sometimes she would take me along. I could always tell what families were inside the stores by recognizing their carriages and coachmen standing by. Later on, one seven-passenger limousine to a family was the standard mode of transportation for such errands. The mother or the mother-in-law would share her car with the young matron two or three times a week on these shopping sorties. The chauffeurs were completely trusted and the Madame was very dependent on her chauffeur. I think he did more for the ladies than their grown sons, who were busy with their own households. The chauffeurs would park their seven-passenger touring cars as near to the stores as possible and then stand in front, waiting for the Mistress to appear. They all had a very good time, standing there and gossiping. I always wondered what they were saying.

There weren’t any traffic lights in those days to help in crossing the street. We did have the assistance of attentive door men who stopped the traffic and took the women shoppers across the street in the middle of the block.

Across the street was Korner and Wood, a gem of a bookstore. One entered a narrow aisle with book shelves on either side, filled to the ceiling with sets of hand-tooled Moroccan leather covered books. The works of Dickens, Thackery and most of the classics came in sets bound in bright red and green, or subdued brown leather. There were modern novels and histories in all sizes and shapes. Mr. Korner was always there among his books, and greeted all his customers as they entered his shop.

Euclid and East l05th Street became another ‘crossroad’ of daily life, with its excellent markets, shops and entertainment centers. Hoffman’s Ice Cream Parlor was a special favorite of the young set, as was the Alhambra Theatre with its legitimate theater productions. The l05th Street Market was huge and catered to the fashionable households by offering delivery service. The lady of the house would call Southworth’s Grocery or the Taylor Fish Company on the telephone and have everything delivered by wagon. Sometimes, in order to buy something special, she would have her chauffeur drive her to the market to assist her. The chauffeur would carry even the smallest package.

Wood and Company, the plant, flower and seed store, was on Euclid Avenue near 105th Street for years. It was purchased by Mr. and Mrs. Warren B. Parker, who ran it like a country store-informal, friendly, helpful. Mrs. Parker told me that her most difficult challenge was an order for 500 hyacinths, to be delivered in full bloom at a wedding reception in the middle of April. One of her good customers came to her in January to ask if she could count on the hyacinths in April, when her daughter was getting married. She had her heart set on using the plants throughout the house at the wedding reception. Mrs. Parker figured out very carefully when she should start her hyacinth bulbs so they would be in full bloom, as she had promised. Seven days before the wedding they were not in bloom; six days before they were not in bloom; five days before there was no sign of bloom. The second day before the wedding, as if by magic, all the plants burst into bloom and their delicate fragrance premeated the store.