Main Body

Montage

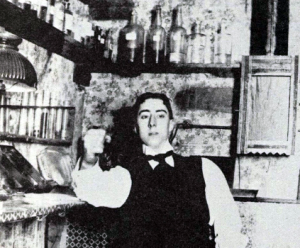

My brother Dudley, being ten years my senior and over six feet tall, made a big impression on my young life. He made a big impression on the world, too, with his genius in electronics. Dudley was always experimenting with scientific concepts and was, even as a young boy, an inventor.

One of the early electrical achievements of my brother was inspired by his fascination with Alexander Graham Bell’s new invention -the telephone. At the time few persons appreciated the potential of this instrument. Dudley wanted to communicate easily with his boyhood friend, John A Vincent, living a quarter of a mile away. So, when only fourteen years old, he built two phones and connected them with a telephone line. The wire was installed from barn to barn between our two houses, both on the same side of the street.

He made the two phones by cutting out circular discs from tintype photos. These metal discs (the same principle used in modern phones) vibrated with the voice when the mouthpiece of the transmitter was spoken into. He also used tintype in the receiver (resembling the type used later on commercial phones) with the electric cord coming out of the narrow top. He made a wall-type phone out of an oak back board, with a box attached containing the batteries. This needing static electricity to operate, he made Leyden Jar wet batteries. On top of the box he built a small shelf which held memo paper and pencil.

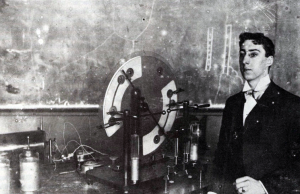

As electricity did not come to Cleveland residences until 1901, Dudley could not use gas for his electrical experiments. So he built his own gas engine and dynamo. He created his own electric power plant in our basement in 1893. Dudley’s genius was early recognized by Dr. Dayton C. Miller, who frequently came to our house to observe Dudley’s electrical experiments.

Dudley’s affiliation with Miller led both to his youthful fame and early tragic death as a pioneer to X-Ray.

The Cleveland Medical Library Association asked me to tell of my brother’s work; and my narrative is quoted from their Quarterly Journal, Volume XX, No. 1, published January, 1973:

Dudley B. Wick, Jr.:

Young Pioneer in X-Ray

“With his genius and his untiring research, Dudley helped conduct the earliest experiments in the development of the XRay; his Roentgenograms made on February 14, 1896 were the first ever photographed in the United States. He died a pioneer when only twenty seven from over-exposure, as the dangerous power of X-Rays was then not known.

Dudley was gifted with many God-given talents-music early, and athletics later. He majored on the violin, and when ten years old he played Schumann’s Traumerai, accompanied by his mother, before a large, enthusiastic audience in the former Opera House for a charity.

One of Dudley’s earliest interests was photography, which became a great help to him later in X-Ray and shadowgraphs. When twelve he built his own dark room and chemicallaboratory and did his own developing and enlarging. Next electricity dominated him. As only gas was available for residences, he equipped all our gas chandeliers with electric buzzers which sparked to light the gas jet fixtures. He installed in our parents’ master bedroom a switchboard which operated the lighting fixtures throughout our home. He next built a burglar alarm system and wired each door and window to an annunciator which he built to show the location of a burglar’s attempt to enter while at the same time activating a fifteen inch electric bell. In 1890 he installed wires from our house to others in the neighborhood for telegraph instruments, later changed to telephones, for which he made diaphragms out of tintypes and made Leyden Jar Batteries for the needed static electricity. The next year he installed intercommunicating phones in our parents’ bedroom, kitchen, laundry, stable and his lab.

In 1892, when he was sixteen, there was only gas in private residences. He needed current for his electrical experiments, so on his precision lathe he turned patterns, had a gray iron foundry cast them, machined the metal and made a gas engine that was remarkable, as it ran efficiently. He then wound the coils and made his large dynamo. The gas engine’s ‘put, put’ exhaust noise from the basement window could be heard throughout the neighborhood, but no one objected as all were fascinated with the young man’s electrical experiments. This is how Dr. Dayton C. Miller, (Uenowned physicist and head of electrical engineering at Case, learned of Dudley’s accomplishments in electricity, and he became a frequent visitor to my brother’s basement laboratory.

Dr. Miller was amazed at Dudley’s ingenuity and he invited Dudley to visit the laboratory at Case School of Applied Science after school and on Saturdays. Dudley was then atttending University School, which required all students to remain through 4:30, so Dr. Miller persuaded him to transfer to Central High School to get his chemistry and mathematics mornings and leave by noon to arrive at Case Lab.

Dudley gave to Dr. Miller an induction spark coil which he had wound by hand on his lathe. It had greater capacity than any owned by any other technical school.

The first public announcement of the discovery by Professor Roentgen of Warzburg Univesity in Bavaria of the XRay appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on January 9, 1896. It intrigued Dudley, and he asked Dr. Miller why they could not duplicate the X-Ray by using the Crookes Tubes which Dr. Miller had bought at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893. Dr. Miller had been too busy to ever experiment with them, so they had lain three years in a glass cabinet in Case Lab. After tireless efforts Dr. Miller and Dudley succeeded in producing the powerful new X-Rays. The first Roentgenogram ever photographed in the United States Dudley made of his own left hand on February 14, 1896. The original glass plate is in the archives of Case.

The newspapers followed their progress closely. Each morning the Cleveland Leader and Plain Dealer (also the afternoon dailies, the Press and the then Cleveland Wor/d) would publish usually on the front page what Dr. Dayton C. Miller and Dudley B. Wick, Jr. had accomplished the night before at Case laboratory. Detailed accounts were accompanied by shadowgraphs showing the X-Rays. However, Dudley had extreme modesty. He hated publicity. He had hero worship for his teacher, Dr. Miller. So I still recall Dudley pleading with his father, ‘You, Father, are president of the Bank. Please use your influence and urge the newspapers to never publish my name in the headlines or articles. Use only Dr. Miller’s name.’

Like Edison, he turned night into day. I recall Father and Mother phoning Dr. Miller many a mid-night saying, ‘Please send Dudley home as he has an exam in trigonometry or chemistry next morning.’ Dr. Miller usually responded, ‘We’ve almost got it, please let Dudley help me a little longer.’

I have given notarized photostat copies of the many articles and also prints of the glass plates of X-Rays to Dr. Genevieve Miller for the Howard Dittrick Museum of Historical Medicine and to Dr. Robert Schofield for the archives of Case. I also gave the latter the thiry-four original glass photoplates of the X-Rays Dudley made.

In 1904 when Dudley was only twenty-seven he was promoted to chief engineer and head of the engineering and research department of the internationally known North Electric Company. Patents of his inventions continued to be granted. He died on March 1, 1905.

Warren C. Wick”

Further quotes from the Case Western Reserve University monthly magazine, “Images”, published March, 1976, talks about my brother’s work:

“Dudley B. Wick Jr. was an electronics genius. He had served as a willing guinea pig for early experiments in X-Ray. His left hand was the first object ever X-Rayed in the United States; February 14, 1896.

He invented a device for holding a patient in a comfortable position during the procedure. Wick hand-lathed an electric induction coil, the most powerful in existence at the time. He gave it to Case. Wick’s coil supplied the electricity for their XRays and for Dr. Miller’s research.

Dayton Miller and his assistant, Wick, began a grand tour of the United States to give lectures. Dr. Miller demonstrated how the X-Ray worked, either on himself or his assistant, Wick.

In later years, a doctor designed a glove which would protect the hand while using the X-Ray equipment. Dudley B. Wick, Jr. did not benefit from the glove and suffered a fatal reaction to the rays. He died March 1, 1905 from overexposure to the deadly rays, a pioneer to X-Ray. He was only 27 years old.”

After Dudley’s untimely death Dayton Miller gave up his work with X-Ray, and spent the rest of his life studying sound. Although never stating his reasons for abandoning that research, it was known he was deeply affected by the death of his heroic young assistant.

Brother Dudley was my hero. He was always so patient and generous in helping me with my lessons and interests. His untimely death hit me hard. I was just at the age when I was ready to embrace my older brother as a friend and pal … and, as I reached out to him, he was gone.

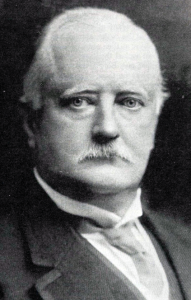

DR. GEORGE CRILE

During World War II Dr. George Crile developed new methods of treating infections and surgical shock suffered by the wounded soldiers. And he discovered new methods for handling transfusions. His innovative techniques saved many lives. George Crile argued for use of the new gas anaesthesia, it being far superior to either chloroform or ether when operating on the wounded. He received many honors and worldwide recognition for his humane advances in combat procedures.

It was during that wartime situation, when he was on active duty at the front, that Mildred my wife was involved in a family drama featuring Dr. Crile. She can best relate the story in her own words:

“In World War I, I had three brothers in the war. We were living in Calhoun Falls, South Carolina during that period.

“A newspaper reporter from Atlanta called Father around midnight, reporting he’d just learned his son, Andrew, had been killed.

“There was a more than sad silence the rest of the night, broken only by the mournful sound of a hoot owl in the pine trees. Weeks went by.

“Father tried, from generals down to lesser rank, to find out what had happened. But no trace of Andrew. He tried his old friend , Ambassador Herrick, who was in Paris during the war; still without result. Time dragged on. Finally he tried his friend, Dr. Crile, at the front with his Lakeside unit. And Dr. Crile, in the midst of his busy day and night work with the dying and wounded, took time off -and located my brother in a hospital near the front line trenches, where he’d been taken after being gassed.

“Andrew hadn’t wanted to let his family know he’d been gassed, as he knew they would worry. And he was told that his family would not be notified of his condition. Only soldiers badly gassed and taken back a long distance from the front were written about in the papers.

“My brother Andrew, then, was sent home from the hospital and proved to be in good shape. I always felt Dr. Crile had performed a miracle, and had personally delivered Andrew to his family.”

After the War was over, Dr. George Crile sought a new challenge. In 1921, in collaboration with Dr. Frank E. Bunts and Dr. William E. Lower, he founded the Cleveland Clinic. At that time, most of the doctors and hospitals were located downtown. Building the Clinic at the corner of Euclid Avenue and East Ninety-Third Street was far-sighted, in terms of the growth of the community. The great “Clinic Disaster”, the tragic fire that destroyed the Cleveland Clinic, touched my life in an odd way. During the early winter months of 1929, a cast of Yale Alumni practiced hard on our Yale show -dress rehearsal scheduled for May 15, the day of the terrible fire. We never had the rehearsal, and because of the enormous grief over the conflagration, the play was cancelled.

Three weeks later I was on the train going to my 20th reunion at Yale, and Doctor Crile sat opposite me. He was going to Yale to see “Barney”, his son, graduate. He had kindly asked me to join him for dinner in the dining car.

So recently after the tragedy, I marveled at his composure and courageous spirit. I did notice his eyes were sad.

All mankind has benefited from Dr. Crile’s research, not least of them the goiter patients. A very good thing for Cleveland, as we live in a goiter-belt. Goiter patients have entered the Clinic from all over the world. A Maharaja came from India, with his family and large entourage. His children went to Laurel School the winter he was here. Naturally, the Laurel pupils were intrigued by the students from far-away India wearing their native dress.

Another interesting patient was Randolph Hearst. Marian 102 Davies came with him, causing much gossip in Cleveland.

I wish it were possible for Dr. George Crile to know how his small Clinic was destined to grow to cover several city blocks. And how his young son, “Barney”, would himself develop into a distinguished surgeon. Recently “Barney” was given an Honorary Fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons in London; the first time this honor had been bestowed upon a father and son.

LAURENCE NORTON

Mr. Laurence Norton was part of the distinguished family that was part of the Oglebay Norton Company. He was president of the Western Reserve Historical Society from 1934 to 1960, and was responsible for having the Society take over and combine the John Hay and Bingham-Hanna Houses. The Norton family generously endowed the Napoleon Room at the Society when the two houses were united.

I recall an unusual story Laurence told me. Laurence was an attache to Ambassador Herrick. He had to attend the receptions given once a week at the Embassay in Paris. There was a genteel old lady who always came to those receptions, too. She wore the same black dress which, to tell the truth, was a little shabby. And she ate as if she hadn’t had any food all week; she was suspected of taking home a little sandwich or two in the clean white handkerchief in her dress pocket. There was much speculation about her, and I’m sure she was probably shunned by the Grand Dames.

Laurence happened, later, on the same ship going to Athens with Lord Kitchner. He was so surprised to see the poor little old lady dining at his table, and, later, on the platform sitting next to Lord Kitchner, who was delivering a speech. He was later told by Lord Kitchner she was the distinguished sister of General Robert E. Lee.

MRS. WILSON B. HICKOX

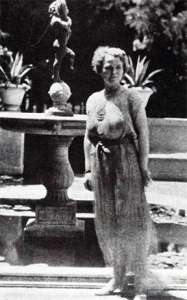

My beautiful sister-in-law, Mrs. Wilson B. Hickox, when eighteen, had her portrait painted in New York. And, while it was necessary for her to go to the artist’s studio to sit for her painting, her parents would not allow her to go there without a chaperon. Her young brother, George Calhoun, would sometimes accompany her. He would dutifully sit for hours on a stiff backed chair, bored to death; but, being trustwor.thy, he never moved.

The artist painted a full-length portrait of her, measuring about six feet. Her dress was pink chiffon over pink taffeta, with a low-cut neck. Her blonde hair, blue eyes and pink cheeks make a lovely vision of a young girl. Her son, Charles Hickox, has his mother’s portrait hanging in his living room.

LEONARD C. HANNA, JR.

Leonard Hanna, Jr. was a very cultured man and discerning in taste. He loved art and left his excellent collection to our Museum of Art. He was a devotee of the theater, and a very generous supporter of Karamu. He had an apartment in New York City for the winter season, where he went to enjoy all the Broadway openings. He was helpful to Cole Porter, financing his first musical, and was fond of Monte Woolie, often a guest at his country estate. He also had as his guests many Hollywood stars.

His country estate featured a house built in 1462. It had been an old English Inn between London and Dover and was brought over in pieces from England by Mr. and Mrs. Edmundson S. Burke, to be used for their guest house at their Hunting Valley country estate. It had been constructed of oak and plaster, and topped with a tile roof. The timbers were numbered and, once here, everything was put together again and rebuilt, exactly as it had all been originally; doors, hinges, locks, chimneys, tile roof, etc.

It was then taken down the second time, with timbers again numbered, and rebuilt on Leonard Hanna’s Hilo Farm, on Little Mountain Road. The living room was two and one half stories high. Leonard had the grounds landscaped with formal flower gardens, including a large swimming pool.

This beautiful pool was the setting for many lovely parties. A very hospitable man, he had a bar by the pool and a butler to take your order. One weekend Joan Crawford, the famous movie actress, was visiting him. At dinner she wore a ruby and diamond necklace with matching ruby and diamond ear· rings, a jewelry ensemble that had just been given her. After dinner, seeing Leonard’s stunning Weimaraner dog, she knelt down, dramatically enfolding the dog in her arms. Sad to relate, she lost one of her fabulous earrings. The dog being prime suspect, the head of Leonard’s kennels was called in and set to watching the canine, now isolated in a pen. Miss Crawford made such a fuss though, bemoaning the fact of her jewelry ensemble being ruined, that she spoiled the evening for the rest of the guests. There was, still, a happy ending of sorts. The next day her earring was recovered from the animal’s pen.

Once, when my wife Mildred was shy and single, she had an unexpected visit with Leonard Hanna. Her car broke down right by the entrance to Leonard’s house. Leonard, very cordial, said he would send for his chauffeur to go see what the trouble was. She prayed the chauffeur would find something wrong; it would have been too embarrassing had it started right up. On the other hand, she hoped it would take a little while to fix, as she was enjoying herself immensely, visiting with Len.

He introduced her to Monte Woolie, then staying with him. Monte became a close friend of Leonard’s at Yale; he was in the Class of “11”. He was also the star in “The Man Who Came to Dinner.” Of course, she recognized him by his famous beard. It was after 1:00 in the afternoon, though both men were in their bathrobes, and, she thought they were drinking orange juice. She refused to join them, being due for lunch at the Fayette Browns. Little time elapsed before the men started on their second orange juice, and the chauffeur came in to report the car had been fixed. After second thought, Mildred decided that they weren’t drinking orange juice at all, but rather orange blossoms -for an eye opener!

EDWARD GRASSELLI

My friendship with the brilliant and unique Edward Grasselli began in kindergarten at Hathaway Brown School. There were four of us who formed a clique that continued through our days at University School. There was Ed, myself, Prescott Ely and Ralph Perkins.

We four boys always attended each other’s birthday parties. Edward’s home was where the present Auditorium is now located, on the corner of St. Clair and Bond Street (East Sixth Street). His house was a large, red-brick, stonetrimmed, three-story house set back on a deep lawn. On Ed’s hirthdays, we always played musical chairs. He had a musical chair that played tunes, when you were able to get there to sit on it. Oh, I remember it very well; it was wonderful. It had painted ornaments on the back; the back was quite high and the seat would go down when you’d sit on it. It played marvelous tunes. It came from Germany.

Ed did not like new clothes. So, arriving at Hathaway Brown he’d go to a blackboard and get two pieces of white chalk, grind the chalk into a powder and put it on a wooden desk chair, then slide around on it until his suit became shiny. On returning home, Johanna, the governess, would notice the state of his suit, and she would say next morning, “Edward, you must put on another blue suit.” But, determined, Ed would again repeat his chalk treatment, for he didn’t want to look like Little Lord Fauntleroy, much preferring to look like the rest of his classmates.

At University School, Ed, Ralph and Pres were known as the “three muskateers”. They used to pull a stunt in the main study of the school, where all the desks were. They would open up the lids of the desks, spread their arms wide, and rush down the aisles: as their arms hit against the raised lids, they’d bang down against the lower desks. It made a terrific noise, like a gattiing gun. But, by the time the principal of the school would arrive, the three boys had disappeared. Even· tually they were caught, and were quick to promise that they would never do that again.

In his maturity, Edward Grasselli was the kindest man I have ever known. Before the days of the present electric traffic light, traffic policemen with semaphores were stationed at all the prominent intersections. Ed felt sorry for them, particularly in winter, standing out on those corners and operating those signals. When he no longer drove his own auto, Ed would have his chauffeur drive up and down the thoroughfares of Cleveland during the holiday season. Approaching the traffic policemen, he would hand each one a handsomely wrapped Christmas present. I think he used to purchase them all at Cowell and Hubbard, from his classmate, Sterling Hubbard.

He also went around to the different fire stations and gave gifts to the hardworking fire fighters. Ed was loved and idolized by the working classes. He was one of those souls who brightened up all who came in contact with him, making anyone near him feel happy. Ed was brilliant beyond belief. His humor and original sayings were unequaled. At the Tavern Club, he always sat in his chair, located in the main lounge near the northeast corner of Prospect and East Thirtieth Street. His picture is now on the wall above his chair. Tavern Club members have great respect for his memory.

PATRICK CALHOUN

Patrick Calhoun was the father of my wife, Mildred Calhoun Wick This courtly Southern gentleman with his dynamic personality dramatically affected the direction of growth in Cleveland in the late 19th century. Born in Clemson, South Carolina, in the home of his statesman grandfather, John C. Calhoun, he was destined to leave his mark on the world. He grew up to be a commanding figure , standing over six feet tall, with piercing blue eyes. At the age of only 26, he was the senior partner in the firm of Calhoun, King and Spalding. It is still in existence as the oldest and most prominent law firm in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1890, Patrick Calhoun came to Cleveland to attend a railroad meeting, as legal counsel for the Southern Railway System. At the meeting’s conclusion, he realized he had some time until his train left at 8:30 p.m. He understood that Garfield’s Memorial was soon to be dedicated and he wanted to see it. The monument had been built through popular subscription across the country; and, coming from a good government family, he had contributed to its construction. His grandfather, John C. Calhoun, was Vice President of the United States, and selected as one of the five most outstanding United States senators.

Mr. John Harkness Brown took Mr. Calhoun in his carriage to see the monument. As they drove out Euclid Avenue and arrived at Wade Park, Calhoun said, “Where does Cleveland grow from here? I’ve not seen a vacant property all the way out Euclid Avenue.” Mr. Brown told him the loveliest view of the monument was from the brow of the hill of what was known as the Heights.

Mr. Brown drove Mr. Calhoun up Cedar Glen Hill. Crossing the farmland at the top of the hill, Mr. Calhoun asked whose property it was. He was told that it was the Streator Dairy Farm and covered about 200 acres. It occurred to Mr. Calhoun that Cleveland had no direction to go but up this hill to the Heights. He also noticed that on this August day it was several degrees cooler than down in the city. Mr. Calhoun asked, “How much do they want an acre?” Mr. Brown replied he’d never heard they wanted to sell the land. But Mr. Calhoun persisted; “I’d like to offer them ‘x’ dollars an acre, but I’d like to know, before I leave on that train for New York, whether or not I’ve made a commitment.”

Mr. Brown hurriedly called the Streater family together. They said -“Don’t let Mr. Calhoun out of town until he’s bought it. We’ve never heard of such a high price for farmland.” The end result was Mr. Calhoun paid the Streator family $50,000 down for the property, and, when he left for New York had indeed bought the old Streator farm.

The farm started at the top of Cedar Glen Hill, with the northern boundary Overlook Road; out east to Coventry Road; and bounded on the south by Cedar Road. The land had been razed for farming; Dr Streator se\1ing the trees for railroad ties and planks (for the to\1 roads). It was truly raw land, with no water, no sewers. Mr. Calhoun began plans for development of it as a deluxe allotment for elegant residences. He announced plans for a $5 million residential construction project, to be known as the Euclid Heights Al1otment. A rather high-sounding name for a piece of land long known as “Turkey Ridge”, because of innumerable wild turkeys to be found there. He employed an English landscape architect to layout the curved streets; and he gave them English names: Berkshire, Derbyshire, Coventry . . .

When Mr. Calhoun explained his proposed project to John D. Rockefeller -he responded with a million dollar loan, seeing it as an excellent investment. Mr. Calhoun placed heavy restrictions on each deed. Requiring large lots; each house to cost a minimum amount; built three stories high with a basement; and to be a designated distance from the curb. Itwas heavily zoned for single residential occupancy. Many of Cleveland’s leading citizens bought lots -and built magnificent mansions on Overlook Road, looking down upon the city.

Patrick Calhoun hired architect Frank B. Meade to design a fine home for his family, so he could bring them here from the South. This house -at 2460 Edgehill Road in what is now Cleveland Heights -is where Mildred was born. The house has been designated a landmark by the Cleveland Heights Landmark Commission.

He thought it was important to have a church in the new community; so he gave the land that created St. Alban’s Episcopal Church. (The property on the corner of Euclid Heights Boulevard and Edgehill Road was once a race track, which accounts for its unusual oval shape.) The other development he considered important was having a first-class 18 hole golf course. So he created the Euclid Club. By this time he had built for himself a Florentine mansion (one of the largest houses built in Cleveland), and had installed a ninehole golf course around the villa; this was to be the beginning of the new Euclid Club course.

To complete the IS-hole course, Mr. Calhoun purchased from Mr. John D. Rockefeller, who owned it, the needed adjoining land. Mr. Rockefeller insisted though, stating in the deed, “No golf can be played on my land on Sunday.” In order to play IS holes on Sundays then, members had to play Mr. Calhoun’s nine holes twice.

The Euclid Club opened on July 4, 1900 in Euclid Heights, with one of the finest clubhouses in the country. It had gray shingles with wide porches.

Mr. Calhoun secured W. H. (“Bertie”) Way as the professional and had him layout the 18 hole golf course. It was only the second golf course built in Cleveland. The first was the old Cleveland Golf Club in Bratenahl, later to become the Country Club.

My parents were early members of the Euclid Club, so I enjoyed it from the time I was a young boy at University School. We boys and girls from Millionaires’ Row took the street car up to Euclid Heights and often spent all day Saturday there. We competed in golf, tennis and putting-green tournaments. I remember the shower baths were refreshing because of the unusually cold water that came from a spring. There were dances Saturday nights and holidays, where I saw many of my friends.

In July, 1907 the first National Amateur Golf Championship was played on the Euclid Club course. The large gallery included members of the Club -and, the world’s most talked of man, John D. Rockefeller. When asked by newspapermen how to get rich, he responded: “Save a little money -not next week, but this week. Have you tried it?” None, apparently, had.

To help beautify the entrance to Cedar Glen Hill, and to help the approach to Euclid Heights, Mr. Calhoun gave to the city of Cleveland the land at the foot of Cedar Glen. It included a large tree lawn circle to aid all divergent traffic adjoining the former Lilac Lane.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer stated: “University Circle is nationally famous for its beauty and culture. It was founded in September of 1902. Mr. Calhoun donated a large strip of land to the city for park purposes, as he was interested in building a cultural center here. A lovely curving boulevard was built through Wade Park adjoining Euclid Avenue. Uni· versity Circle came into being as the beautiful entrance to the Park System.”

It is with pride I tell of Patrick Calhoun, the father of my wife. His forceful personality brought excitement and adventure into the worlds he entered.

MYRON T. HERRICK

Myron, a young boy from Lorain, Ohio, was asked to visit Mr. and Mrs. Jeptha Wade. Lorain was then a small town, just west of Elyria. When this small-town boy arrived in Cleveland, he was bewildered by such a large city. He also was greatly impressed by the large and handsome residence of the Wades.

Mr. and Mrs. Wade gave a dance in their ballroom the first night of his arrival as their guest. He was aware at the dance that his red necktie was too bright, that his red socks were too loud. He noticed the other boys wore subdued dark blue suits made to order by their fathers’ tailors. His suit, while purchased at the best store in Lorain, had trousers too short for this fast-growing boy. He was a tall handsome lad with broad shoulders and large for his age.

Embarrassed about his clothes, he wanted to leave the party. But just then Mrs. Wade, realizing his unhappiness, invited him to dance with her. She put him at his ease immediately. He enjoyed dancing with her so much .. . he continued dancing with girls his own age the rest of the evening. This same young boy later became a very prominent Clevelander -Myron T. Herrick. He became president of the Society for Savings Bank and, later, governor of the state of Ohio and Ambassador to France.

Governor Myron T. Herrick built a large red brick house at the top of Cedar Hill on Overlook Road. Living in this house made the Wade house he’d visited as a boy seem to shrink in size. Later when Governor, of course, he lived in the Governor’s Mansion.

He was appointed Ambassador to France by President Taft. And, having lived in the beautiful city of Paris, he was no longer awed by the size of Cleveland. During World War I he had the courage to stay on in Paris as the German army advanced toward the city.

ELIZABETH MATHER

Mrs. William G. Mather had an extraordinary, creative mind, with the capability of completing her plans. It is said she had a desk, paper and pen in the back of her Rolls Royce so as not to be wasting time just sitting in a car doing nothing.

Mr. and Mrs. Mather were lovely and charming hosts. Mr. Mather, almost thirty years older, looked very young and handsome with his neat white mustache and alert, courteous manner.

Mr. and Mrs. Mather gave inspiring and unusual New Year’s Day parties. She had young boys from Trinity Cathedral dressed in their choir robes singing for her guests. They would walk through the house carrying lighted candles and their alto voices sounded like angels on high.

The Dean of Trinity Cathedral and several Episcopal Ministers were there. It made one realize the Christmas season was conceived in religion apart from our material world.

In one room hot wassail was served from big silver bowls. In the dining room, you could have eggnog or anything else you chose to drink. (Most of the guests lingered in the dining room.)

Her son, Jim Ireland, and his wife lived near the coal mines. His mother gave him a birthday party, turning a large room in her basement into the facsimilie of a coal mine. There were little cars of coal coming out the entrance of a coal mine. There wasn’t room at the party though for the faithful mule who, with one eye covered, ·took the miners into the mine. It was the most unique party ever given in Cleveland.

Elizabeth Mather had her “Day at Home” every Thursday afternoon. During the winter, she received her guests in her house; in summer, tea, dainty sandwiches and cakes were served in her garden overlooking Lake Erie. Some members of the Garden Club of America were visiting Mrs. Mather on one of these afternoons, enjoying her gorgeous gardens and manicured lawn running all the way from Lakeshore Boulevard to the lake. She inquired what she could do for their pleasure. One guest, not realizing Lake Erie was a vast body of water, said she would enjoy a ride around the Lake.

This beautiful estate was named “Gwinn” in memory of Mr. William G . Mather’s mother. Elizabeth loved the beautiful aspects of life … and “Gwinn”, I think, is a fitting monument to her memory. To us who loved her, it is alive still with her eternal grace. Elizabeth Mather left “Gwinn” to her son, James D. Ireland, with the hope that he and his family would live there. She had also contemplated the idea of using the estate as a conference center. Cornelia and Jim Ireland decided to turn the property into a civic center though, and succeeded in accomplishing this with the cooperation of University Circle, Inc., an organization which Mrs. Mather helped to inspire.

Mr. James Ireland has made “Gwinn” available for civic groups and out of town dignitaries to use for meetings, luncheons and dinners. Tea is served by the hostess from an exquisite tea service, replete with delicate porcelain cups and saucers. They have maintained the house with its original art treasures and English antique furniture; the exterior of the mansion has been restored to its original beauty.

WILLIAM G. MATHER

The strong character and moral fiber of Mr. William G. Mather is perfectly illustrated by this incident occurring while he was a student at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. This college was run by the Episcopal Church. When a freshman, William carved his initials on a church pew in the Trinity Chapel. For this he was meted a one dollar fine by the college.

Years later, still sorry about those initials, it was his wish to build a new chapel for Trinity College! Asked permission to do this, the Trinity trustees hastened to give their approval. They had no idea what a magnificent chapel Mr. Mather was planning to build.

The chapel was built of grey flagstone. He also gave the musical chimes in the steeple; the clear notes of the hymns still ring over the campus.

The pews by the chancel run the length of that chapel, facing each other, and both choir and students occupied them. Mr. Mather sent to England for artisans and skilled craftsmen to carve wooden figures of early Biblical saints and apostles. These delicately carved figures, painstakingly executed, were about three feet tall and placed at each entrance of the pews.

No royal chapel in old England could be more beautiful. To my knowledge, carved wooden figures are in no other chapel in the United States.

The Mather chapel was being built when the 1929 Crash occurred. Mr. Mather, like many of his friends, found it difficult having available funds to meet expenditures as construction progressed.

For a time, the men worked on cheerfully without any pay, until Mr. Mather was able to reimburse them. They recognized the privilege of participating in such a lofty, spiritual endeavor.

Devoted friendships developed among the workmen. After the Trinity chapel was completed, they celebrated for many years with dinner once a year.

Mr. Mather was Dean of Trustees of the College until his death. At the time of the dedication of the new Trinity Chapel, Mr. Mather, in true modesty, stated he hoped the new chapel would in some way make up for his carved initials when he was a freshman student . . .

Another side of William Mather’s personality reveals itself in the following anecdote:

William Mather often took groups of friends or business associates out on the steamer “Pontiac”, which was the flagship of the Cleveland-Cliffs Corporation. Once, when he had a group of men aboard, the famous Peter White joined them at the Soo Locks.

At dinner that night, one by one, the various men rose to toast Peter White with the champagne he loved. Peter’s face grew longer and longer though, as toast after toast was proposed and the bottle went lower and lower without his having had benefit of any of the ‘toast’.

William Mather, noting the frustration of his honored guest, stood up; proclaimed: “We are on the steamer ‘Pontiac’ and I hereby decree what will be known hereafter as the ‘Pontiac Rule’. That he who is drunk to . . . may also, verily, drink!” Peter White’s face changed rapidly, and, immediately -he downed the biggest glass of champagne available.

ED WYNN

Ed Wynn was sponsored by Texaco on the national radio where he was known as the Fire Chief. He was the best tonic that we had during the depression and lifted up our spirits with his homespun jokes, old-fashioned philosophy and cheery laugh. One of his clever sayings was: “He invented an eleven foot pole for those you wouldn’t touch with a ten foot pole.”

Later he had an hour program each week on television. In addition to his Fire Chief hat, he had many other hats which he would change often during his program. I think today his act would be considered rather corny and silly, but his kind, good, and gentle nature would be appreciated.

My cousin, Bill Chisholm, was back at Yale for his reunion. His class sent Ed Wynn an invitation to come to Yale in June and be their guest for Commencement. Ed Wynn naturally thought of Yale’s June graduation class and concluded that he was to be given an Honorary Degree. Imagine the chagrin and embarrassment of the President of the Class who had to explain that the class had no authority to award honorary degrees, but that all the Yale class loved him and wanted him to join them as guest of honor in their good times.

Texaco sent the entire Yale class Fireman hats and complete uniforms, even including their leggings, while all the other Yale Reunion classes had to buy their own costumes. I was invited to the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity house after the Yale-Harvard baseball game to meet Ed Wynn, their guest of honor. I was urged to waltz-clog on top of a table and to sing “Antoinette Burby” that Cole Porter had written for me. Ed Wynn liked my dancing and singing so much that he asked me to join his new musical show he was going to put on in the fall. I thanked him, but I refused as I wouldn’t want to be traveling on the road so much. I also told him that I enjoyed living at home with my mother.

He asked me for my mother’s name, as he wanted to write her a note. I replied: “Mrs. Dudley B. Wick.” He said, “I don’t want her last name; I want her first name.” He wrote my mother on a wrapper of Handsome Dan smoking tobacco, which I still have, and said: “Dear Emma, I am captivated by your son’s dancing and singing and I have offered Warren a five-year contract to join my new musical show that will open in the fall in New York, but he prefers to stay with you. I want you to be my guest when we play in Cleveland. Yours, Ed Wynn.”

STERLING BECKWITH

Sterling Beckwith was a wonderful man. I loved him. He was the uncle of my University School classmate, Sterling Hubbard. My friend, Sterling Hubbard, was a marvelous athlete, the best pitcher University School ever had on their baseball team. But he never went to college. When he graduated from University School, he went right into the family store, Cowell and Hubbard. He did a fine job there for many years, but, in later years, got restless, and took to drinking. A very unfortunate situation, and one that affected the operation of the store.

As a consequence of Sterling’s personal problem, his uncle, Sterling Beckwith, had to step in, both to help run the business and try to manage Sterling. The business would regularly end up each year in the red. Sterling Beckwirth, as fairy godfather of the store, was forced to attend annual meetings and ask, “How much is the debt this year?” Then he would write a check to cover the deficit -and they were back in business again. He was also responsible for building the beautiful Cowell and Hubbard edifice situated on the corner of Euclid Avenue and East Thirteenth Street.

This heroic gentleman had been a great athlete in his day. In the early years he won bicycle races and, later, was a champion golfer as well as one of the founders of the Shaker Heights Country Club. He was famous for his Sunday Golf Bag with three clubs. It was his habit, when I knew him, after lunching at the Union Club, to lie on a leather couch in the front lounge with a handkerchief over his eyes. It was my pleasure to occasionally call for him there, motoring him home to Magnolia Drive, where he lived with his half-sister, Mrs. Hubbard. Sometimes, when they invited me to stay for dinner, the waitress would bring him a silver tray with at least a half dozen different bottles of medicine, which, as the different courses progressed, he would take in succession.

My favorite story concerning Sterling Beckwith shows his kindness and generosity. When incumbent upon him to send a wedding present to some young couple of acquaintance, he was sensitive to the fact that the bride would probably prefer to make her own selection. So, he devised a little scenerio, one that was sure to satisfy everyone. He went to his store, Cowell and Hubbard (favorite place for fine gifts of the day), and asked one of his best salesclerks, “What do we have here costing about $75 and so homely that a bride will surely return it to make her own selection?” The clerk didn’t hesitate: “Mr. Beckwith, here’s a lavender vase that’s just what you’re looking for! It comes back unfailingly.”

“Good!” he said. “In the future, when I mail cards to a bride who is the daughter of a good friend, send That.” So, the bride inevitably brought back that vase; she would have the pleasure of selecting, at his store, something of her own liking.