PART 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS

2 Chapter 2: The Toyota Production System (TPS)

Learning Objectives

- Describe the origins and fundamental principles of the Toyota Production System.

- Identify and differentiate between the two pillars of TPS, Just-in-time and Jidoka.

- Name and understand the key TPS tools and techniques that can be leveraged for operational excellence.

Learning Outcome

Apply Toyota Production System principles and pillars to achieve operational excellence.

Topics

- The Scientific Method

- Origins and principles of TPS

- The two pillars of TPS: Just-in-time and Jidoka

- Key TPS tools and techniques

- Leveraging TPS for operational excellence

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is a systematic approach to problem-solving that forms the basis of all continuous improvement methodologies, including Lean Six Sigma and the Toyota Production System. It consists of making observations, formulating a hypothesis, conducting experiments, analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. All improvement methods essentially follow the scientific method. Though terms and tools vary, the key elements remain the same.

Origins and Principles of TPS

The Toyota Production System (TPS) originated in the late 1940s in Japan as the Toyota Motor Corporation’s unique approach to manufacturing. It was developed by Taiichi Ohno and Eiji Toyoda, among others. The two fundamental principles of TPS are continuous improvement and respect for people.

Organizations can adapt the principles of TPS to their specific industries and contexts in the following ways:[1]:

- Understand the Principles: The first step is to understand the fundamental principles of TPS. These include continuous improvement, elimination of waste, and respect for people.

- Identify Waste: In any industry, the concept of waste can be adapted to fit the context. Waste could be time, resources, or even talent. Identifying and eliminating these wastes can lead to more efficient processes.

- Continuous Improvement: This principle can be applied universally. Regardless of the industry, there will always be room for improvement. Regularly reviewing processes and making necessary adjustments is key.

- Respect for People: This principle involves creating a work environment that values employees and encourages their involvement in improvement activities. This can be adapted to any industry.

- Adapt Tools and Techniques: TPS uses a variety of tools and techniques, such as and . These tools and techniques can be adapted and applied to different contexts.

- Customer Focus: Regardless of the industry, the end goal is to provide value to the customer. TPS principles can be used to improve quality, reduce lead time, and enhance overall customer satisfaction.

TPS and Lean manufacturing are flexible and adaptable across different industries and sectors. Though TPS originated in automotive manufacturing, its principles have been applied in healthcare, software development, and even service industries. The success stories of these adopters underscore the universal applicability of TPS principles, with examples from industries as diverse as aerospace, healthcare, and technology.

The Two Pillars of TPS: Just-in-Time and Jidoka

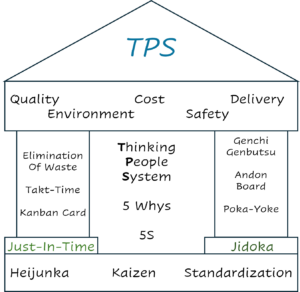

Just-in-time (JIT) and Jidoka are the two pillars of TPS.

Just-in-time:

JIT is a production strategy that strives to improve a business’s return on investment by reducing raw, in-process, and finished goods inventory and their associated carrying costs. It involves producing the necessary items in the necessary quantities at the necessary time.

Jidoka (Autonomation):

is a method for providing machines with the ability to detect when an abnormal condition has occurred and stop work. This enables operations to build quality into each process and separates the workers from the machines for more efficient work.

Key TPS Tools and Techniques

TPS uses a variety of tools and techniques to achieve operational excellence. These include Kanban (a visual signaling system), (a visual management tool), Poka-yoke (error-proofing), Kaizen (continuous improvement), and (production leveling), among others.

In the context of the TPS, understanding the distinctions between a tool, a principle, and a pillar is essential for grasping how TPS operates and drives continuous improvement. Below is a breakdown of each term:

Tool

Definition: A tool is a specific technique or method used to implement processes within the production system. Tools are practical instruments that helps teams achieve desired outcomes.

Examples:

- 5S: A methodology for organizing the workplace to improve efficiency and safety

- Kanban: A visual scheduling system that helps manage workflow and inventory levels

- Value Stream Mapping: A tool used to visualize and analyze the flow of materials and information throughout the production process

Explanation: A tool is actionable and can be directly applied to tasks or processes. Tools are often the means through which principles are executed in a practical setting.

Principle

Definition: A principle is a foundational belief or philosophy that guides decision making and behavior within the production system. Principles provide the rationale behind why certain practices are adopted.

Examples:

- Continuous Improvement (Kaizen): Seeking ways to improve processes, products, and services on a constant basis

- Respect for People: Emphasizing the importance of valuing employees and fostering a collaborative environment

- Customer First: Prioritizing customer satisfaction and quality in all decisions

Explanation: Principles make up the underlying philosophy that informs the use of tools and the establishment of practices within TPS. Principles shape the culture and mindset of an organization.

Pillar

Definition: A pillar is an essential component or framework that supports the overall structure of TPS. Pillars represent key areas of focus that uphold the system’s effectiveness.

Examples:

- Just-in-time (JIT): Producing only what is needed, when it is needed, and in the amount that is needed

- Jidoka (Autonomation): Building quality into the production process and empowering workers to stop production when issues arise

Explanation: Pillars are critical to the stability and success of TPS. They integrate various principles and tools, providing a robust structure that supports the overall goals of efficiency, quality, and continuous improvement.

| Term | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tool | Specific technique or method for implementation | 5S, Kanban, Value Stream Mapping |

| Principle | Foundational belief guiding behavior and decisions | Continuous Improvement, Respect for People, Customer First |

| Pillar | Essential component supporting the system’s structure | Just-in-time, Jidoka |

In conclusion, tools are the practical applications, principles are the guiding philosophies, and pillars are the foundational structures that together form the cohesive and effective Toyota Production System. Understanding these distinctions helps organizations effectively implement TPS and foster a culture of continuous improvement.

Kanban (Visual Signaling System)

Kanban is a visual system for managing work as it moves through a process. The goal of Kanban is to minimize the inventory within a system by signaling when to order, produce, or ship inventory based on consumption further downstream. Additionally, it identifies bottlenecks in a process through outages, emergency order signals, and frequency of production as flagged by Kanban “cards.” It is designed to establish a pull inventory system limiting Work in Process (WIP) and automatically coordinates production across the value stream or overall production process. It can eliminate the need for expensive computerized systems, such as MRP, and reduces the complexity of a process.

A Kanban system uses some form of visual indicator, such as a card, that is pulled as inventory is consumed. The card acts as a signal to trigger production and/or ordering upstream. (Inventory within a process is referred to as a “.”) The inventory level for supermarkets, , and finished goods are set based on the flexibility of processes further upstream. For a process that can operate efficiently with small batch sizes, quick turnover, and fast production times, the size of the supermarket or inventory within the Kanban can be reduced, leading to less waste and lower costs.

Kanban cards do not have to be physical in nature; they may be created electronically. Their functionality remains the same. Examples of the automation of these card signals can include optical windows, inventory weight monitoring, or the use of sensors to detect materials in a given spot.

The frequency monitors the inventory system and calculates turns. In this way, cards can be added or removed to adjust the system.

An example of a Kanban from everyday life is at the grocery store. Stores use the shelf inventory as an indicator of purchases that then define the need to order more stock. This need is signaled via the scanning of bar codes at the register.

Kaizen (Continuous Improvement) Examples

- Toyota Motor Corporation (Automotive Industry): The origin of Kaizen lies in the Toyota Production System developed after World War II. Toyota’s focus on waste reduction, worker inclusion, and continuous incremental improvement paved the way for its evolution from a small car manufacturing company to a global automotive leader.

- Ford Motor Company (Automotive Industry): Ford’s ability to stay relevant today amid changing industry dynamics showcases its ongoing commitment to Kaizen.

- New Balance (Shoe Industry): New Balance successfully applied the Kaizen technique to improve product quality and reduce production lead times. By employing Kaizen principles, it continued to innovate, producing high-quality athletic shoes that cater to the specific needs of athletes.

- John Deere (Agriculture and Heavy Machinery): John Deere embraced Kaizen to enhance productivity and product quality. This commitment to continuous improvement has allowed it to maintain a strong market presence for over a century.

- The Ritz-Carlton (Hospitality Industry): The Ritz-Carlton implemented a daily improvement process where employees met to discuss guest experiences and suggest improvements.

- Nestlé (Food Industry): Nestlé, the largest food company in the world, has used a tool often associated with Kaizen called value stream mapping. The company mapped out a new bottling plant using value stream mapping to ensure that processes were as efficient as possible.

- Hospitals (Healthcare Industry): Hospitals around the world have embraced Kaizen to improve patient care, enhance operational efficiency, and optimize resource use. For example, in a hospital setting, Kaizen methodologies are used to redesign patient flow, standardize processes, and implement visual management systems. Kaizen is also used to prevent material outages in sterile processing and operating rooms.

Andon (Visual Management Tool)

Andon is a system that notifies management, maintenance, and other workers of a quality or process problem. The alert can be activated manually by a worker using a pullcord or button, or it may be activated automatically by the production equipment itself. Often, a system will include a means to stop production so that an issue can be corrected.

An example of Andon is the engine maintenance light in a car. It is programmed to light up at a predefined mileage or time interval to signal that maintenance is due in order to prevent damage to a car’s functionality.

- Toyota (Automotive Industry): Toyota is well-known for its use of Andon in its production line1. When a problem is detected, the worker pulls the Andon cord to stop the production line, allowing the issue to be addressed immediately.

- Amazon (E-commerce Industry): Amazon uses Andon cords in their fulfillment centers. When a problem arises, such as a damaged product or technical issue, workers can pull the Andon cord to signal for help.

- Honeywell (Manufacturing Industry): Honeywell uses Andon systems in its manufacturing processes6. The system allows employees to quickly identify and address issues, improving efficiency and product quality.

- 3M (Manufacturing Industry): At the 3M Tape Manufacturing Plant in Minnesota, the facility experienced a significant loss of production time due to the slow response time of support personnel to unanticipated production disruptions. To address this problem, they implemented an Andon system to alert support personnel immediately when a problem was detected.

- Hospitals (Healthcare Industry): Hospitals have adopted Andon systems to improve patient safety. For example, auditory Andons are used in infusion pumps to signal that a medication is nearly gone or if there is a defect in the tubing[2][3].

- Daily Life: Even in daily life, there are examples of Andon systems. For instance, the dashboard of a car is a type of Andon system, as it alerts the driver to the fuel level and if more fuel is required at that time.

Poka-yoke (Error-Proofing)

Poka-yoke is a Japanese term that means “mistake-proofing” or “inadvertent error prevention.” A Poka-yoke is any mechanism in a Lean manufacturing process that helps an equipment operator avoid mistakes. Its purpose is to eliminate product defects by preventing, correcting, or drawing attention to human errors as they occur. This includes designing fixtures that allow parts to be loaded in only one way or requiring two-palm button activation of a machine to ensure that the operator’s hands are clear and safe.

An example of a Poka-yoke is present at almost every gas station. The diameters of the diesel fuel and regular gas nozzles are shaped differently, as are the nozzle receptacles in cars. The idea is that this will prevent someone from accidently putting diesel fuel into a car that runs on regular gasoline and thereby damage the engine.

Below are tips for integrating Poka-yoke into existing processes without disrupting operations [4]:

- Identify the Problem: Begin by pinpointing specific areas within your process where errors frequently occur.

- Find the Root Cause: Conduct a thorough analysis to determine why these errors are happening. You can use tools like the Five Whys Method.

- Determine the Correct Poka-yoke Method: Choose a Poka-yoke method tailored to the specific process and requirements.

- Implement and Test the Poka-yoke: Test the chosen plan and evaluate the results. Make sure the Poka-yoke doesn’t disrupt the process or create new problems.

- Train Employees: Ensure that all relevant employees are trained on how to use the Poka-yoke system[5]. This includes understanding its purpose, how it works, and what to do when an error is detected.

- Measure the Efficiency: Assess the success of the implemented Poka-yoke by measuring its impact on error reduction and process efficiency.

- Review and Improve: Poka-yoke is part of continuous improvement. Regularly review the effectiveness of Poka-yoke measures and make necessary adjustments.

Remember, the goal of Poka-yoke is to prevent errors from occurring, not just to detect them. By following these steps, you can integrate Poka-yoke into an existing processes without causing disruptions. In service industries such as healthcare, it can be more difficult to define Poka-yoke solutions due to the industry’s heavy reliance on human decision making. For example, when issuing prescription drugs, the physician or provider must choose the correct drug and dose given the patient’s condition. Prompts can be entered into the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) for guidance based on specific patient parameters, but there are too many variables considered to eliminate human decisions in this instance.

- Overreliance on Technology: While technology can aid in implementing Poka-yoke, it is crucial not to rely on it too heavily. The goal of Poka-yoke is to prevent errors from occurring, not just to detect them.

- Resistance to Change: Change can be challenging for any organization. Resistance from employees, lack of buy-in, or resource constraints can hinder the successful implementation of error prevention measures. It is essential to address these challenges proactively by fostering open communication, providing sufficient training and support, and clearly articulating the benefits of Poka-yoke. The goal of Poka-yoke is to foolproof a system.

- Initial Investment: Implementing Poka-yoke systems often requires a significant upfront investment in terms of equipment, technology, and employee training. This initial cost can be perceived as a barrier for some organizations, particularly smaller businesses with limited budgets.

- Inadequate Training: Proper training is crucial for the successful implementation of Poka-yoke. Without adequate training, employees may not understand how to use the system effectively, leading to misuse or underuse.

- Lack of Continuous Improvement: Poka-yoke is not a one-time fix, but a part of continuous improvement. Organizations need to regularly review and update their Poka-yoke measures to ensure these processes remain effective and relevant.

Kaizen (Continuous Improvement)

Kaizen is made up of two Japanese words: “kai,” meaning change, and “zen,” meaning for the better. Kaizen is any business activity that continuously improves all functions and involves all employees, from the CEO to the assembly line workers. It also applies to processes, such as purchasing and logistics, that cross organizational boundaries into the supply chain. By improving standardized activities and processes, Kaizen’s aim is to eliminate waste. When implementing Kaizen systems, it is important that all employees know they have a role in identifying and implementing changes. This organization-wide inclusion is a critical element in establishing a culture of continuous improvement.

Heijunka (Production Leveling)

is a technique for reducing unevenness in a production process and minimizing the chance of overburden. Heijunka, also called production leveling or production smoothing, is a technique for reducing (unevenness), which in turn reduces Muda (waste). Heijunka is crucial to the development of production efficiency in Lean manufacturing.

These tools and techniques are fundamental to Lean Six Sigma and can be leveraged to drive operational excellence in any organization.

Leveraging TPS for Operational Excellence

Organizations can leverage TPS principles and tools to drive their operational excellence. By focusing on continuous improvement, eliminating waste, and implementing built-in quality, organizations can increase efficiency, reduce costs, increase employee satisfaction, and enhance customer satisfaction.

Below are numerous real-world success stories of companies that applied TPS principles:

- The Toyota Motor Corporation: Toyota’s own success story is a testament to the effectiveness of TPS[6]. The system has helped Toyota become one of the world’s leading automobile manufacturers, with both high-quality products and efficient manufacturing processes.

- New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI): NUMMI, a joint venture between General Motors and Toyota, saw significant improvements after implementing TPS. Employee absenteeism fell from 20% to a steady 2%, and the cars that were produced had the lowest defect rates in the U.S.

- Engine Assembly Line Improvements: Toyota was able to pinpoint and rectify minute inconsistencies in its engine assembly process by employing Six Sigma principles. This lead to a substantial decrease in defects.

- Resilience during Supply Chain Disruptions: During the supply chain disruptions triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, Toyota fared better than many of its competitors. This resilience was attributed to the principles of TPS.

Chapter Summary

References

: George, M. L. (2002). Lean Six Sigma: Combining Six Sigma Quality with Lean Production Speed. McGraw-Hill. : Liker, J. K. (2004). The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer. McGraw-Hill. : Ohno, T. (1988). Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Productivity Press. : Womack, J. P., & Jones, D. T. (1996). Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation. Simon & Schuster. : Snee, R. D. (2010). Lean Six Sigma – getting better all the time. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma. : Dennis, P., & Shook, J. (2007). Lean Production Simplified: A Plain-Language Guide to the World’s Most Powerful Production System. Productivity Press.

: Liker, J. K. (2004). The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer. McGraw-Hill. : Ohno, T. (1988). Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Productivity Press. : Womack, J. P., & Jones, D. T. (1996). Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation. Simon & Schuster. : George, M. L. (2002). Lean Six Sigma: Combining Six Sigma Quality with Lean Production Speed. McGraw-Hill. : Dennis, P., & Shook, J. (2007). Lean Production Simplified: A Plain-Language Guide to the World’s Most Powerful Production System. Productivity Press.

ChatGPT and Perplexity were used to research these topics.

More about TPS:

The Toyota Way [7]

We aspire to realize the vision of Mobility for All, while pursuing our mission to Produce Happiness for All through creating the value of the Toyota Way based on our spirit of foundation. This is the path to an ideal society, and it is pioneered by each and every team member.

Act for Others

We strive to keep the perspectives of our customers and stakeholders at the core of our efforts every day. Putting ourselves in others’ positions, we go beyond the impossible.

Work with Integrity

We always consider where today’s work should take us and how it impacts those around us. We forge a path to our objective with integrity and honesty.

Drive Curiosity

Taking a personal interest in everything, we ask questions to discover the mechanics behind phenomena. This mindset generates new ideas.

Observe Thoroughly

Humans sense things instinctively in ways that machines cannot. We bring together hard data while personally seeing, feeling, and interpreting the situation, exercising Genchi Genbutsu to discover the most creative and best solutions quickly.

Get Better and Better

Today and every day, we take ownership to sharpen our skills and the skills of others with heart, mind and body to meet the evolving needs of our customers.

Continue the Quest for Improvement

We believe in the natural ability of people to change things for the better. Every improvement, regardless of size, is valuable. Encouraging both incremental and breakthrough innovative thinking, we seek to evolve with Kaizen and never accept the status quo.

Create Room to Grow

Focusing on what is essential, we eliminate waste and manage our resources carefully to create room to grow. This is the foundation for agility and the cultivation of new ideas for the future.

Welcome Competition

We welcome competition, without ego. It pushes us to improve and better serve our customers and society, creating more value and a better experience.

Show Respect for People

No work is solitary. No job is a one-person endeavor. We make the most of diverse perspectives, turning differences into fortitude as one team. With a fundamental respect for people, we create an environment where all feel welcome, safe, and heard, and everyone can contribute their best toward meaningful goals.

Thank People

We owe our existence to our customers, members, partners, stakeholders and communities. We say “thank you” to everyone whom we encounter today.

- https://www.apitchdeck.com/blog/kaizen-in-action-real-life-examples-of-entrepreneurs-who-thrived-through-continuous-improvement. Accessed October 1, 2024. ↵

- https://safetyculture.com/topics/andon/ ↵

- https://www.virginiamasoninstitute.org/how-can-andons-improve-patient-safety/ ↵

- Oleg, Pochepskiy, April 2015. “Poka-yoke in manufacturing: methods, advantages, disadvantages, and examples.” Cleverence, Bubai Silicon Oasis, Dubai, UAE. https://www.cleverence.com/articles/business-blogs/poka-yoke-in-manufacturing-methods-advantages-disadvantages-and-examples/. Accessed October 1, 2024 ↵

- https://nulab.com/learn/project-management/what-is-poka-yoke-technique-how-to-do-it/ ↵

- https://www.mfg.marshall.edu/lean-manufacturing-made-toyota-the-success-story-it-is-today/ ↵

- Life at Toyota Blog. https://careers.toyota.com/us/en/culture. Accessed October 1, 2024. "The images from this site are included under fair use and not subject to the CC license of this book." ↵

Visual signal system to control workflow.

Example: Using sticky notes on a board to show what homework needs doing.

Error-proofing systems to prevent mistakes.

Example: USB ports that only fit one way.

Automatically stopping work when problems occur to prevent defects.

Example: Like a washing machine stopping if the lid opens.

A visual management tool that signals problems in a process, allowing for immediate attention.

Example: Like a student raising their hand in class when they need help, an Andon light tells workers when a machine needs attention.

A method of leveling production by distributing work evenly to reduce waste and improve efficiency.

Example: Like spreading homework assignments evenly throughout the week instead of cramming them all in one day.

Organized storage area for quick part pickup.

Example: School supply cabinet where everything has its place.

Basic materials used in manufacturing before any processing.

Example: Like the flour and sugar you need before baking cookies.

A method in pull systems where cards (Kanban) signal the need to produce or move materials.

Example: Like deli tickets indicating it's your turn, Kanban cards signal when to make or move items.

Unevenness in workload.

Example: A restaurant overcrowded during mealtimes, but empty at other times.