As the Ohio-Erie canal made Cleveland the focal point of northern Ohio transportation in the 1820’s, so the railroad era, beginning in the 1850’s left a lasting mark on the growing city. The success of the canal in providing an exchange of goods and service was not lost upon the railroad promoters who quickly discovered the advantages of rail, and the disadvantages of water. The railroads brought industry and prosperity to Cleveland in the 1870’s and 1880’s, although they had their start as early as the 1850’s. At first many people were reluctant to accept this new form of transportation. The industrialists were the first to see the commercial possibilities of rail. By the 1880’s seven railroads served the city. To stimulate passenger service, railway guides were printed in the 1850’s, among them The Ohio Railway Guide (1854), which described in extravagant terms the delights of rail travel and the sights to been seen along the way, including the bridges.

It may be best to start with the origins of the lines now entering Cleveland. Located in the Western Reserve of the northwest territory, Cleveland was reached with difficulty by land routes along the shores of Lake Erie or by water from Buffalo. Not until the Ohio Canal was opened in 1827 did a north-south route move goods from inland state to market. Ohio granted charters to railroads, by act of the Legislature, to meet the increasing needs of the state for improved transportation, because the canals, funded by the state of Ohio, were found to be a financial disaster, in spite of the fact that they had moved substantial tonnages and people over the 600 miles of mainline canals in the state.

Although the foresighted Canal Commissioner former mayor of the village of Cleveland, realtor and lawyer, Alfred Kelley, obtained a franchise for a Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad in 1836, his was not the first railroad in Cleveland.

The Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad, organized in 14 March, 1836, was the first one to serve Cleveland. A group of businessmen formed the Cleveland, Warren and Pittsburgh railroad to build a railway from Cleveland to the Ohio River and on to Pittsburgh. These men chose the route judiciously, for it eventually became one of the heaviest traveled routes in the nation. It still carries iron ore from docks on the lake front to the mills of Pittsburgh. The railroad had financial troubles, and in 1845 reorganized, eliminating Warren from its name. Still in trouble, at a public meeting on 23 March, 1847, it was decided to ask Cleveland residents to back the enterprise with public funds. In an election held in April the electorate voted to contribute $200,000 of the city funds for stock to aid in construction.

It took another three years for the road to reach Hudson, and another few years before track was laid to Pittsburgh. On 4 March, 1852, the mayor of Cleveland and the entire City Council boarded a train and rode to Wellsville on the Ohio River, where they joined in a three-day celebration. “[1] In 1864 the C. and P. Railroad replaced a wooden trestle across Tinker’s Creek with a 200-foot long, 20-foot wide masonry arch bridge. The four arches were approximately 50 feet wide. In 1901 the line abandoned the viaduct.

This railroad is still in existence as it was leased by the Pennsylvania Railroad for 999 years. The C. and P. eventually became the main line of the Pennsylvania, from Cleveland to Bedford, Ravenna, Alliance, Steubenville, Wheeling and Pennsylvania.

The C. and P. took an easy route from the lakefront passenger and freight station erected on city-owned property, i.e., “The Bathe Street Tract” set aside by the city fathers for navigation and commerce at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. Climbing from the lake level and crossing Euclid Avenue at Wilson Avenue (now East 55th Street) a few farsighted people protested that this doomed Euclid Avenue, and further objected to the loss of access to the shoreline. Leonard Case, with large real estate holdings east of Case Avenue (East 40th Street) promptly built an “industrial park” to be served by the railroad. At Warner Road, the railroad followed Mill Creek southeast. The only bridge of note was a stone arch over Tinkers Creek in Bedford — still in use — although now widened to double track. In 1911, the Pennsylvania Railroad built the ore docks on Whiskey Island at a cost of $3,000,000, and crossed the Cuyahoga on joint trackage with the New York Central, each using its own single track on a shoo-fly arrangement. Not until the present lift bridge (discussed in Chapter III) was built did the bridge become double-tracked, where it still shared track rights, although now both roads belong to Conrail. About 1912 the Pennsylvania Railroad spent several million dollars in building steel girder bridges in Cleveland.

The need for east-west movement promoted a Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad to the east. This original road to the state line opened in 1852. The successor was the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern, formed in 1869 by merging the Michigan-Southern and Northern Indiana Railroad (Detroit to Chicago), with the Cleveland and Toledo and the Buffalo and Erie Railroads into a system extending from Buffalo to Chicago. This railroad was principally a passenger road to provide transportation to the growing west. The Lake Shore and Michigan Southern became the water-level route between New York and Chicago. When acquired by Vanderbilt, it crossed the Cuyahoga River on a swing bridge at the mouth of the river. The road then healed southwest to Berea, to avoid the deep Rocky River gorge. Here the railroad crossed over the east branch of Rocky River on a four-arch stone masonry bridge, made from local sandstone. Berea was famous for the manufacture of grindstones and for its stone quarries. The original bridge is still in use, but widened with concrete side spans. Another fourspan stone arch bridge at Painesville crossed the Grand River at a height of 90 feet. When this bridge became obsolete, it was replaced in 1909 by a four-track, single concrete arch. Proportioned as a solid masonry arch, reinforcing steel was used to unite the concrete into a solid monolith.

A classic stone masonry arch built in 1898 for the successor to the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad crosses over Liberty Boulevard in Gordon Park. The bridge was designed by Charles F. Schweinfurth, eminent Cleveland architect, whose Romanesque buildings are now to be found on the register of the National Society for Historic Preservation. It is a double-track bridge, 150 feet long and 40 feet wide. This bridge is reinforced according to the Melan system. Professor Joseph Melan (1853-1941), a Viennese, became an international figure in the engineering world. The simplified structural analysis and contrived a novel and economical construction method. His principal was to construct a relatively light fabricated steel arch between piers, which served as a centering to support the forms for pouring concrete and as stiff reinforcement, to which, when necessary, additional bars could be added. Melan’s system was used in building the first concrete arch-a twenty-foot span in Golden Gate Park in 1889. This structure may have influenced the design of the Schweinfurth bridge. However, unlike the Cleveland bridge, the concrete of the Golden Gate span had an imitation, rough-stone finish. Schweinfurth’s use of natural stone with colored decorations and ornaments is unique.

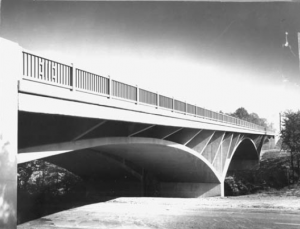

As reinforced concrete became popular, in the early decades of the 1900’s, the New York Central erected a fine example at Willoughby, over the Chagrin River. It is a massive ribbed-arch, designed by Samuel Rockwell, Chief Engineer of the railroad, assisted by O.W. Irwin. Several stone arches exist in Elyria and Wakeman.

The Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, although chartered as early as 1836, did materialize until 1845. Mayor Alfred Kelley, pushed the completion of the road. A $200,000 stock subscription from the city helped considerably. William Ganson Rose tells us that at one time the C.C.C. Railroad was built by the physical labor of its president, directors and financial backers to keep the franchise active.[2]

The Cleveland. Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad terminated on the lakefront, where it crossed the main line of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern to reach the roundhouse and docks. The railroads shared a “Union Station” on Front Street between West Third and West Ninth. The C.C.and C. railroad crossed the Cuyahoga River and the Ohio Canal near where the Carter Road Bridge is now. By following the Walworth Run to Clark Avenue, it reached Berea adjacent to the Lake Shore and Michigan-Southern tracks, There the tracks crossed Rocky River on a stone-arch bridge. Although abandoned, and with one arch removed, the single track structure still spans river. Its replacement, a reinforced concrete structure built in 1909, is virtually a duplicate of the original bridge.

With discovery of oil in Pennsylvania, and the need to transport it to markets, the Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad was founded. Chartered in 1848, the right-of-way for a broad-gauge road was acquired, and the railroad reached Youngstown by way of Warren in 1857. Transporting coal by rail from the Warren area put the Pennsylvania and Ohio Canal and important tributary of the Ohio-Erie Canal, out of business. The Atlantic and Great Western Railroad, imposing in name only, leased the Cleveland and Mahoning in 1863 for a direct rail line to New York City.

The railroad crossed the Cuyahoga River at Broadway, adjacent to the Standard Oil Company, and followed Mill Creek and the Kinsgbury River valleys into Cleveland. The docks for the transfer of the coal to lake freighters were situated along an extensive river frontage north of Columbus Road. For years a coal loader operated under the High Level Bridge, to serve the freighters that were coal-fired.

Continuing northward, the railroad crossed under Detroit Street. Here may be found the oldest bridge in Cleveland still standing and in use. It was originally built for the Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad Company and dates from 1853. The bridge-support consists of skewed double stone arches, each 15 feet wide, with the tracks on a curve. Both arches are about 17 feet from the top of the arch to the ground. The overall length is about 55 feet center-to-center of abutments. Curving under the Superior Viaduct, the railroad continues to the dock still referred to as NYPANO Docks, one of the railroad’s many names.

After the Civil War, the Erie Railroad leased the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad to get to Chicago. The latter went into receivership in 1880 and was recognized as the New York, Pennsylvania and Northern Ohio Railroad (NYPANO) and leased again to the Erie in 1883. In 1896 the Erie acquired the NYPANO by stock purchase. In 1938 the Erie was in financial trouble and bought the Cleveland and Mahoning stock to save rentals of the leased line.

The Atlantic and Great Western obtained track rights from the C.C.C. and St. Louis line and ran passenger trains to the station under the Detroit-Superior Bridge, now occupied by “Diamond Jim’s restaurant. Why the Atlantic and Great Western did not enter the Union Station is not known. It is interesting to note that General John H. Devereux, a Clevelander, was credited with saving the Union during the Civil War, by virtue of being Superintendent of Military Railroads. As General Superintendent of the C. and P., President of the L.S. and M.S. in 1869, President of the A. and G.W. and of the Big Four in 1876, he had excellent opportunity to weld four lines into one unit, one hundred years ago, and he failed to act. Deveraux is also interesting because of a collection of engineering drawings which he made in the 1850’s and 1860’s. This collection is in the Western Reserve Historical Society. The drawings include many bridge structures, both iron and masonry. One drawing is labeled “Cuyahoga Bridge”, a Howe truss, but its location has never been established.[3]

The Baltimore and Ohio railroad, the oldest in the country, was incorporated in 1827. It had by 1853, crossed the Appalachians as far as Wheeling. Some of the greatest engineers of the latter half of the nineteenth century were employed by this road: Jonathan Knight, Benjamin Latrobe Jr., Wendell Bollman and Albert Fink.

In 1909 the B.and O. acquired two small lines to extend its trackage into Cleveland. One of these lines was the Cleveland and Valley Railroad, organized in 1871 to extend rail by way of Akron and the northern end of the Ohio-Erie canal. For the right-of-way and for a 99-year lease the B. and O. paid $265,010. Bankrupt in 1880, the railroad was recognized in 1894 as the Cleveland Terminal and Valley Railroad with a branch line to Newburgh. The second line was a small one serving Lorain from Tuscarawas Valley via Medina. It was extended into Cleveland in 1895 by way of the big Creek Valley and terminated at Literary Street, where it connected with the Erie. All the trackage that the B. and O. acquired was single-track and has so remained to this day. The Baltimore and Ohio crosses the Cuyahoga River at West Third Street and Quigley on a bascule — one of the twin bridges. The fixed span at Denison Avenue is above the navigation limit.

The former Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad started out as the narrow gauge Conotton Valley Railroad, which ran from Canton to Cleveland. In 1883 passengers were discharged at Ontario and Huron in 1882 to a temporary depot at Commercial Street. A freight station without trackage and some bridge abutments remain. After reorganization in 1885 as the Cleveland and Canton, the now standard gauge road was extended to Zanesville. Several mergers with some additional small roads extended service to Chagrin Falls. Renamed as the Wheeling and Lake Erie, the line opened up coal fields in the Zanesville area. The road in Cleveland is single-track and is now part of the Norfolk and Western System. The bridge crossing the Cuyahoga River is not used.

The history of “Nickel Plate Road” is most interesting. The name “Nickel Plate,” which was coined by a Norwalk editor, intended to indicate a superiority much as we use the term “chrome plated”. The road was formerly known as the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad. The line was to parallel the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern route from Chicago to Buffalo. Organized in 1881, the line sold $16,000,000 of stock in three days. It was built in twenty-one months! In order to traverse the City of Cleveland, two small railroads — the Rocky River Railroad (from Lakewood to West 58th Street) and a part of the old Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad — were bought for the right-of-way. The latter line, popularly named the “dummy line”, was so-called because at first the trains were run with “dummies” — steam locomotives with boilers entirely concealed to resemble streetcars. A multiple-span timber trestle bridge, built about 1865, carried the dummy line over Kingsbury Run near East 55th Street. But soon the Nickel Plate was erecting major wrought-iron viaducts to replace the cumbersome wooden structures. As loads increased and production of iron became practical and economical, the iron truss bridge dominated the scene. By the 1880’s all major railroad bridges were of wrought-iron.

The Nickel Plate hired the best engineers available to execute its determination to connect Chicago and New York City by the shortest route. To cut the running time, the Rocky River gorge was to be spanned at the lake by a high trestle, as was also the Cuyahoga Valley. The bridge at Rockport, (now Rocky River) was a multiple-span Bollman-truss bridge, built in 1882, It was 673 feet long and 88 feet high — a remarkable structure in its day.

A viaduct over the Cuyahoga River was likewise a wonder in its time. Its length of 3,000 feet contained 2,500 tons of wrought-iron. The river span was a 222-foot swing-draw. The first plan was to cross the river with a short, low-level bridge and to bore a tunnel through the west bank. However, this plan was dropped in favor of a double-track iron bride, 68 feet above the valley. Work on the one hundred odd masonry piers was completed in May of 1882; but it took most of the summer to erect the iron towers and girder spans. The Cuyahoga span was the last link in the system to be completed. And at 6 p.m. on 25 August 1882, the drawspan was fitted into place. The structure was built by the Cleveland Car and Bridge Company, in accordance with plans designed by W.M. Hughes, designing and supervising engineer of the movable span. Over one hundred sheets of detailed drawings were prepared. At first the draw was manipulated by hand and took four minutes, but later steam-power opened the span in about one minute. The Cleveland Herald reported that “when the massive structure was moved for the first time, it swung around easily without friction or jar, to the satisfaction of William Hughes and Henry Claflin, designer and builder, who were anxiously watching it.”[4]

Three days after construction of the swing span had been completed, the first train passed over the viaduct. The Bellevue Local News, on 2 September, 1882, reported the event:

Not a jar or vibration not calculated for in the construction of this great piece of engineering and mechanism was perceptible. The locomotive, as it crossed the draw going towards the eastern end had got fairly on its way, heralded in triumphal blasts from its whistle the tidings of the tactical completion of the great iron thoroughfare…[sic] aware of what is going on, by the sight of No. 20 as she steamed away, high overhead, a few moments to transverse the 3000 feet of tracks stretched across the valley on its girders of iron. Although it was to be expected, yet the sight of the locomotive and its load brought multitudes out to see it.”[5]

This construction marked the completion of the Nickel Plate Road between Buffalo and Chicago. The first passenger train, from Chicago, entered Cleveland at Rocky River on 31 August 1882. The Cleveland Herald described the event:

The depot was beautifully decorated with flags and bunting, and a large crowd awaited the train as it dashed up. An P. Eells met the party here and accompanied them into Cleveland. The entrance of the road into this latter city is by way of a wonderful system of bridges, viaducts, and grades, and evidence of the fact that a great triumph in engineering has been accomplished. The system of bridges embraces more than 3,000 feet, and carries the tracks through the heart of the “Flats” above all streets and roads.”[6]

On 23 October, 1882, the first regular passenger train left in Chicago for Cleveland, and at the same time a train started westward from Cleveland.

The train started its journey by rumbling slowly across the great viaduct over the Cuyahoga Valley, passing first at Columbus Street. Having passed under Lake shore and Michigan Southern through an arch, the train ran almost in a beeline to Rocky River, pausing an instant on the east bank before crossing the “gigantic” bridge to the west side. Then it drew up in front of a neat little depot which has been christened River Bank, directly opposite the magnificent country home of Dan P. Eells.”[7]

The viaduct over the Cuyahoga was twice remodeled, in 1904 and in 1944. George Roberts, President of the Pennsylvania Railroad and outstanding engineer, expressed admiration for the design and construction of the Nickel Plate’s iron bridges. These were engineered to withstand 10 to 15 percent greater stress than the bridges on the Cincinnati Southern, then reported to be the best-built in America.

The Nickel Plate has the best grade and most direct route across northern Ohio. Both the New York Central and the Pennsylvania cross the Cuyahoga River at near lake level. These roads also cross the city streets on overhead brides, hence have steeper ruling grades. The Nickel Plate, now part of the Norfolk and Western crosses the Cuyahoga at 68 feet above water and passes under Cleveland streets both east and west.

After the first passenger train had completed its run, the New York Central bought controlling interest in the stock and manipulated the line until 1915, when the Attorney General ordered it sold under the Clayton Anti-Trust Act. The Van Sweringens purchased control of the railroad and with it the unused right-of-way that is now the roadbed of the Shaker Rapid Transit. They built the Cleveland Union Terminal complex, which opened in 1930 (without the Pennsylvania Railroad) serving the New York Central, the Big Four, the Nickel Plate and the Shaker Rapid. The Baltimore and Ohio and the Erie entered at a later date.

In order to reach the Public Square Terminal, a new viaduct and trackage were needed. The impressive Cleveland Union Terminal Railway Bridge, a fixed, high-level structure, crosses the Cuyahoga River directly south of the Detroit-Superior Viaduct, at Irish Town Bend. Built in 1929, this four-tracking railway bridge carries two Cleveland Union Terminal tracks and two Cleveland Transit System (Rapid Transit) tracks. Except for the main span, which is a deck-truss over the river, the thirty spans, are of the deck plate-girder type, and vary in length from 49 feet to 270 feet. The foundations of the structure are about 150 feet below the valley floor, being the depth of the post-glacial material that overlies the native shale. The 3,350-foot structure is owned by the Cleveland Union Terminal Company.

Trains entering the station were originally pulled by electric locomotives.

The bridge was never used to capacity, the magnificent train concourse is now a tennis court, and the train platforms are now a parking lot. The Cleveland Transit System uses the spare tracks.

The Cleveland “Short Line” Railroad, popularly known as the “Belt Line”, was built about 1910 by the New York Central Railroad to interconnect all the rail lines entering Cleveland. This connector railroad is double-tracked. Although it was necessary to cross over or under a good many streets. there are no street crossings. The river was spanned on a 100-foot high structure near Van Epps and Schaaf Roads on the west to East 49th in Cuyahoga Heights Village on the east.

The Newburg and South Shore Railroad serves the steel mills the Cuyahoga Valley and connects with the Belt Line at Harvard Road. This line and that of the Cuyahoga Valley Railroad are short service railroads. The River Terminal Railroad serves Republic Steel, the Cuyahoga Valley Railroad serves Jones and Laughlin, and the Newburgh and South Shore Railroad, the United States Steel Company.

Disaster Leaves a Legacy

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the railroads became the nation’s greatest bridge builders, as they demanded cheap and effective stream crossings. As the railroads grew, the number of bridge failures mounted in the 1870’s and 1880’s. One of these failures happened near Cleveland, at Ashtabula — a disaster that had world-wide repercussions. The story of this bridge failure is worth retelling.

The story begins with William Howe, a Massachusetts housebuilder and millwright, whose invention of the Howe truss, which he patented in 1840, brought about a near monopoly in railroad brig building. The appearance of this truss marked the end of bridges built entirely of wood and the beginning of the use of iron. Designed primarily for railroads, it could be quickly and cheaply built of the greenest wood. Its chief innovation in design was the introduction of wrought-iron vertical rods that could be adjusted and readjusted long after the bridge was in service. The rods had screw-ends with washers and nuts. The parts could be easily shipped and the rods and truss timbers prefabricated, making possible quick assembly. In the Howe truss, timber was used for the chords and for the web diagonals. Iron rods used for the verticals were in tension, and the wood diagonals were in compressions.

After its introduction it became the standard truss for railroad bridges and remained preeminent in the field for thirty years. This popularity was not accidental. A group of determined New Englanders took every opportunity to praise the truss. It was no coincidence that they also happened to control the sales rights of the Howe truss. Howe himself was, as Richard Sanders Allen tells us in his Covered Bridges of the Middle West, “content to be just the inventor, a friendly man who like music and the good things in life which his bridge royalty payments brought him.”[8]

But Howe’s brother-in-law, Amasa Stone, Jr., was more ambitious. Although only a young cabinet-maker who was breaking into heavy contracting, he foresaw the possibilities in a bridge design that the expanding railroads would need. So, together with Azurich Boody, a Canadian-born ex-school teacher and railroad brakeman. Stone scraped up $40,000, and in 1841, bought exclusive rights for building Howe truss bridges in New England, Again, in the words of Richard Sanders Allen, “The two formed a company to build bridges, employed their relatives and friends to learn to work, and laid the foundation for a dynasty of bridge-building firms that would blanket the nation.” [9] But after a few years with Boody, Stone and three brothers and nearly a dozen other men related by marriage, formed their own company.

In 1849 Amasa Stone moved to Cleveland, where, with two new partners, he contracted for all aspects of construction for the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad. This line became a showcase for the Howe truss; most of these bridges were of the deck type on masonry piers, With the original owners now railroad magnates, the rights were sublet to others, Thatcher, Burt and McNary took over the work in Ohio. A younger Stone brother, Andros, with his brother-in-law, Lucius B. Boomer, founded in Chicago the firm of Stone and Boomer. They soon were fabricating Howe trusses for the western railroads. During the 1850’s Stone and Boomer erected bridges on twenty-four different railroads in Illinois, Wisconsin and Missouri.

Meanwhile in Cleveland, Amasa Stone became President of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad and the city’s first millionaire. At this time the Lake Shore crossed the deep gorge of the Ashtabula River on a wooden trestle[Figure XVIII]. Amasa Stone, who, with some justification considered himself a bridge designer, sketched out a new bridge. Basically it was old Howe truss with more than twenty years of success, but all of the components of Stone’s new bridge design were to be made of

wrought-iron. A company engineer ventured to question the wisdom of this innovation, but Amasa Stone would not listen. The length of the structure was 165 feet between massive stone abutments, It was 191/2 feet in width and the truss depth was 20 feet. “Mr. Stone’s pet bridge” had tracks on the deck, which were about 70 feet above water. For thirteen years the bridge carried all the heavy traffic of the railroad’s main line.

Shortly after Christmas, 1876, a northeast gale blowing in from Lake Erie piled snow along the shore. Westbound out of Buffalo came the Pacific Express, two and a half hours late. In the village of Ashtabula no persons stirred out of their homes, except those few whose work kept them out in the cold. An employee of the road, sitting by the fire in his house near the tracks, heard a series of terrific crashes, sounding like explosions. He jumped to his feet when his wife rushed into the room, crying “My God, Henry; No. 5 has gone off the bridge!” Quickly putting on his coat and boots, he ran to the bridge and saw the crumbled mass of cars and iron beams lying at the bottom of the gorge. The train — composed of two locomotives, two express cars, two baggage cars, two day-passenger coaches, a smoking car, and a drawing-room car, and three sleepers — was filled with holiday travelers.

As the train pulled onto the bridge, Dan McGuire at the throttle of the lead locomotive heard a thunderous report, felt the bridge sinking, and, with great presence of mind, opened the throttle valve and drove his engine full steam ahead. Although he declared that “it was like going uphill,” he reached the other abutment and was safe. But one by one the other cars fell through the gap into the gorge below. Of the 157 persons aboard, only one survived the plunge and the fire that ensued. Eighty-three were killed, drowned, or burned to death on the spot.

Charles Collins, Chief Engineer of the railroad, who was highly esteemed by members of his profession, tendered his resignation, saying: “I have worked for thirty years, with what fidelity God knows, for the protection and safety of the public, and now the public, forgetting all these years of service, has turned against me.” However, his resignation was not accepted; the Board of Directors gave him a vote of confidence. But a few days later Collins committed suicide, as a consequence of the attitude of both public and press who blamed him for the disaster.

This disaster carried reverberations throughout the United States. The Iron Age voiced the fears of the people in the statement, ” We know there are plenty of cheap, badly built bridges, which the engineers are watching with anxious fears, and which, to all appearance, only stand by the Grace of God.” The Nation for February declared: By such disasters and by shipwreck are lives in these days sacrificed by the score, and yet except through the clumsy machinery of a coroner’s jury, hardly anywhere in America is there the slightest provision made for inquiry into them. Here are wholesale killings. In four cases out of five someone is responsible for them; there was a carelessness somewhere, a false economy has been practiced, or a defective discipline maintained, or some appliances of safety dispensed with, or some [one] has run for luck and taken his chances.[10]

The coroner’s verdict of the Ashtabula disaster put the blame upon the design of Amasa Stone. Charles Collins, in his testimony, stated that “The bridge was in the nature of an experiment.” So public opinion turned against Amasa Stone. His money was of little use. Six years later he took his own life. While there was the possibility of the failure of one or more of the cast-iron angle-blocks, this bridge was unusual in design. Most Howe trusses built in the East and the Midwest had two diagonal braces and one counterbrace in each panel, with two vertical rods between. Often the end panels had three rods. The testimony stated that there were but five Eastern bridges not so designed, and might be called “Single Howe’, inasmuch as they had but one diagonal brace and one or more panel rods. The Ashtabula bridge failure was due to the insufficient diagonal bracing in the truss design. The dead load caused by heavy members and by the snowstorm were factors. Although the bridge was badly designed, the chief reason for the failure was the general lack of knowledge in handling the new material, wrought-iron.

Three benefits were derived from this disaster. The railroad companies thereafter discarded completely the use of cast-iron. Attempts were made to lighten the weight of structural members. Most importantly, the railroads realized the need to hire specialists in bridge construction — a need which led to the establishment of private and independent firms of civil engineers especially equipped to handle the design and supervise the construction of bridges. [11]

A local benefit grew out of this disaster. Amasa Stone, with some associates, provided the money to purchase a large piece of property on Euclid Avenue adjacent to Case School of Applied Science. This enabled the Western Reserve Academy at Hudson, Ohio, to move to Cleveland in 1881. Stone made on stipulation. The school was to be known as Adelbert College of Western Reserve University. Recently the Case Institute of Technology and Western Reserve University merged to from Case Western Reserve University.

Thus a major bridge disaster left indelible marks on the local history of the Western Reserve and upon the nation.

In all parts of the world the railroads have played a large role in the history of development of bridge-building. Especially significant was their contribution in industrial centers like Cleveland. Although this era seems to have come to a close, and few great railroad viaducts will probably be built in the future, the railroad will remain an essential mode of transportation for certain industrial and commercial purposes; and existing railroad bridges will have to be maintained in good repair.

- Rose W.G., p. 145. ↵

- The account of the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Company is taken from a feature article by Bruce Ellison, "City’s First Railroad on Track to Oblivion," in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Sec. 2 March 14, 1976) p. 1. ↵

- Eric Johnannessen, "Drawings by Some Western Reserve Architects," in Western Reserve Historical Society News (March-April, 1976) p. 15. ↵

- Taylor, Hampton, The Nickel Plate Road (World Publishing Company, Cleveland, Ohio, (1947) pp. 96-7. ↵

- Ibid., p. 97. ↵

- Ibid., p. 131. ↵

- Ibid., p. 144 ↵

- Richards Sanders Allen, Covered Bridges of the Middle West (Bonanza Books, New York, 1952) pp. 112-124 ↵

- Loc. Cit. ↵

- D.B. Steinman and Sara Ruth Watson, Bridges and Their Builders, (Dover Publications, New York, 1975) p. 164. ↵

- Ibid., p. 165. ↵