Main Body

Chapter 4 Cleveland’s Community Development Ecosystem

While Neighborhood Progress, its subsidiaries, and the CDCs it supported were important components of the Cleveland Community Development system, the operational reality was complex and nuanced. The Community Development ecosystem focused primarily on the housing, retail and land use needs of Cleveland’s neighborhoods.

Cleveland’s neighborhoods, especially those on the east side, were losing population. Much of the existing housing stock was pre-World War II. Many wood-frame worker houses were on small lots (40×150), with a single-car garage; the Cleveland doubles or deteriorating small multifamily buildings, all had lingering environmental issues such as lead-based paint, lead water lines and asbestos siding.

As was the case in other older Rust Belt inner cities, retail followed the freeways to the suburbs, with their shopping malls, national chains, and huge parking lots. Local shops that remained clustered along bus/trolley corridors, anchored by neighborhood arcades like Gordon Square, and family-owned convenience stores like Cermak Drugs in Union-Miles, couldn’t compete with chains on price and variety. Hollowing out of downtown department stores accelerated flight to the suburbs. Poorer neighborhoods that depended on public transportation were especially hard-hit, creating food deserts and struggling retail districts.

Along with outmoded retail districts, abandoned factories, a low-performing segregated school system, and weak market demand, Cleveland neighborhoods were at a competitive disadvantage with the surrounding suburbs for attracting new neighborhood investment and residents.

The challenges were not equally shared as the legacy of racism permeates Cleveland from redlining, housing foreclosure and collapsing housing values, to police harassment, lack of health care and employment opportunities.

From the days of redlining to the sub-prime foreclosure and vacant property debacle, to poor health and lead paint housing conditions have remained largely unchanged.

The loss of population density during this period – a decline of over 100,000 between 1980-2000 – led to a patch work of abandoned houses, factories, schools, and hospitals often with related environmental costs and absent owners. Unlike the suburbs, re-developing an inner-city project often involved over 30 discrete stages involving multiple public, private and neighborhood actors with a range of financial resources and regulatory approvals. In the end, the deals needed to “pencil out”, address appraisal issues, and compete financially with suburban green field development. Developing an effective system that responded to both neighborhood need and market demand was a significant achievement of the public private partnership.

Strategy Planning Programs

The city under Mayor Mike White, along with NPI and the foundations, supported for-sale new housing in joint ventures with CDC partners and private builders, along with low income tax credit projects complementing CDC housing rehabs and home repair efforts Many of these for sale housing developments were small, suburban-style subdivisions, while others were in-fill housing woven into the existing neighborhood fabric.

Community development corporations first focused on blight removal, arson prevention, and renovating single-family homes for neighborhood residents of limited incomes. The Cleveland Housing Network, working with local CDCs, pioneered the lease-purchase model for reclaiming distressed properties. The focus was on providing decent housing at affordable prices to low-income residents. That meant keeping rehab costs low, in part by repairing rather than doing major system upgrades, and keeping operating reserve funds to a minimum. This approach solved the immediate affordability issue but had long-term consequences which later required a complicated restructuring by CHN, Enterprise, and others to ensure that the homes remained assets for future owners.

A mix of housing strategies to address the need of equitable development balancing low- income housing with middle income new construction evolved. For example, NPI formed its real estate development subsidiary, New Village Corporation, not to develop upscale housing but to secure two Nehemiah Housing Opportunities Grants from HUD to provide homeownership opportunities for public housing residents and the working poor.

Neighborhood Planning

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s souls…aim high in hope and work,” said architect and city planner Daniel Burnham. Inspiring, but not the best approach to neighborhood renewal, where often communities have organized to keep plans and planners from destroying neighborhood fabric as Jane Jacobs in her account of Robert Moses in NYC so eloquently described. Burnham helped develop the Group Plan that anchored the public buildings along Cleveland’s lakefront even as the Olmsted brothers designed the Emerald Necklace Metroparks. Notwithstanding these achievements, big plans have not been that helpful for Cleveland’s neighborhoods, the destructive impact of Urban Renewal and Federal Highway construction being primary examples.

To counter this top-down vision, planning staff at the City under Norm Krumholz evolved an approach called Equity Planning, which focused on the needs of resident stakeholders. “More choices for those who have few.” This approach became a national model for progressive planners and in Cleveland influenced a generation of urban activists though it never found a political home. Despite its influence within the planning community, there is not an example of an implemented “equity plan,” which is often honored more in the breach than in the observance by developers. For neighborhoods, the Citywide plans and the major infrastructure and roadway investments have been a mixed bag and have not provided much by way of resources for the work described in this account.

Civic Vision 2000 was the downtown plan. It was followed by Connecting Cleveland 2020, the Citywide Plan. Together these foundation-supported efforts had a price tag of $3.5 million. Connecting Cleveland was mostly an aspirational plan that called for neighborhoods of choice, celebrated diversity, was green, sustainable, connected, and built for today and tomorrow. The underlying assumption, however, was that most neighborhoods were likely to remain stable or grow, an optimistic assumption that did not materialize.

Nonetheless, each of the 36 neighborhoods identified their vision and priorities. Implementation and management rested with a small, under- resourced planning staff. Neither the mayor nor civic leadership indicated that realizing the plan was their top priority and that they would commit the resources and political capital to make it happen.

In contrast, the 2012 Detroit Strategic Framework Plan, all 347 pages, was far more ambitious in scope, budget and participation. Also, it took the added step of creating an implementation office with staff and operating support to ensure progress and some level of accountability. How successful it was remains to be seen, though the Kresge Foundation’s commitment of $50 MM over five years towards implementation is significant.

Infrastructure Planning: Opportunity Corridor

In 2019, the State of Ohio awarded $365 million for the proposed Opportunity Corridor, a multi-lane vehicular roadway through Cleveland’s Forgotten Triangle. The purpose of the access road plan was sold as a way to increase economic opportunity in a poverty neighborhood where 40 percent of residents lacked cars, while creating direct freeway access for the Cleveland Clinic’s suburban and foreign patients. Little new private investment has been identified at this time, though the city has agreed to build a new district police headquarters and support a new asphalt plant as its primary economic development projects and more is in the pipeline. The Corridor along with construction of a new mega juvenile justice center building in Fairfax has done little to improve neighborhood conditions for local residents who struggled to be heard in the planning process.

So big plans have not been the driver of neighborhood re-investment. What has worked are smaller-scale efforts that have had community input and allow for iteration, adjust as conditions change to solve problems, recover from mistakes, and keep the initiative moving in the right direction. This is an approach used by NPI with its Model Blocks strategy and Strategic Investment Initiative that was improved upon as we learned while attempting to target limited resources for maximum impact.

Model Blocks, Strategic Investment Initiative and Development Action Plans

The goal of building mixed-income neighborhoods of choice went through several versions, from identifying assets and competitive advantages, to an attempt to cluster neighborhoods by type and develop appropriate strategies for each. The term “neighborhoods of choice” was never formally defined in a document with any specificity. Internally it was intended to indicate places where families would choose to live because it was a desirable place, both for new homeowners and exiting resident. The term assumed mixed income not gentrification though this interpretation was not shared by all.

The challenge in adopting this targeting framework was that city council ward boundaries consisted of 10,000 + residents spread out over areas defined by census tracts, not markets, ethnicity or shared history. Each ward had multiple neighborhoods, one CDC and a range of issues and opportunities. Developing a consensus on where to focus and whether to target at all was a challenge in an environment of limited resources and conflicting demands. Nonetheless, we pushed ahead and learned by doing. In the process we found what worked and what didn’t; the approach was more art than science and better suited to an organization like NPI that had no planners on staff.

The “model block” approach was our attempt to build neighborhood fabric by requiring that funded CDCs identity streets within their target areas where block clubs were organized to address safety concerns “eyes on the street”, provide access to home repair/paint programs, develop community gardens on vacant lots, secure abandoned houses and engage residents in various organizing and planning efforts. Later NPI focused on submarkets in six neighborhoods, creating “The Strategic Investment Initiative.” Its goal was to create a comprehensive redevelopment plan around anchor projects and supporting programs. When the mortgage foreclosure wave occurred in 2007 NPI shifted to stabilization strategies for the hardest-hit communities.

Tremont West Strategic Investment Initiative Plan

Tremont West Development Corporation was one of 6 CDCs selected as a Strategic Investment Initiative grant recipient. The following summary from Dennis Keating’s Brief History of Tremont is representative of the SII planning process.

After choosing a Steering Committee and conducting community meetings with residents, TWDC decided to focus on five Tremont sub- neighborhoods: North Tremont, South Tremont, Duck Island, Lincoln Heights and SoTre.

One of the overall objectives was to “establish Tremont’s different districts as neighborhoods of choice to live in through real estate development promoting their strengths.” While different objectives were identified for each of the five districts, TWDC also had overall goals for the entire neighborhood.

- Transportation and infrastructure enhancements.

- Improvements to the West Fourteenth Street bridge.

- Encouraging interaction between block clubs and neighborhood

- Creating a series of connecting walking, biking and driving routes.

- Create parks and community gardens to provide “melting” pot interaction.

- Retain the existing housing alternatives that are affordable for all Tremont residents.

For its target area for model blocks, TWDC chose the blocks immediate adjacent to two new housing projects: Tremont Pointe and Starkweather Homes. A work plan was completed in April 2007 to implement this plan.

Public Sector, Resources and Programs

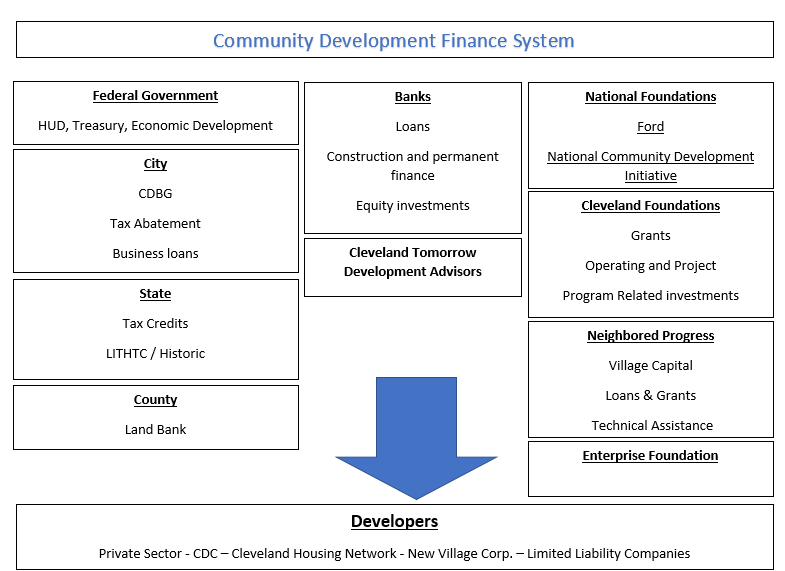

In the absence of an overall neighborhood redevelopment plan for the city and the fact that Cleveland did not have a redevelopment authority, how did neighborhood deals get done, and how did various players co-ordinate their efforts and prioritize development opportunities?

In a low-growth region, the suburbs have a built-in advantage due to costs of environmental remediation, land assembly, appraisal gap issues and weak market demand in the city, all compounded by race and poverty. To overcome this legacy, gap-financing tools evolved, and a savvy cadre of developers and nonprofits have found ways to do business in the city. There are 110 sources of government/foundation financing for neighborhood housing and commercial industrial projects in Cleveland.

Aligning these sources with project requirements is a key component of getting deals done. It involves over 35 discrete stages to get to the finish line starting with a feasible development concept for a buildable site with manageable environmental issues, community consent, zoning, market feasibility, a competent development team, working capital, city subsidies, tax abatement, bank financing, construction, ribbon cutting and occupancy by end users.

Key to successful project development was a network of informal staff relationships in the various sectors—City, CDC’s, banks, and developers—who were able to collaborate on shared development objectives over time. A critical path for developing a project could involve coordinating more than thirty separate major actions on the part of multiple players. The depth of these relationships was a distinguishing trait of the Cleveland system. Another was the Baclava finance system, in which Village Capital played a central role. In brief, the Baclava model meant layered financing to address risk tolerance in an environment where the appraisal value often did not support development costs and acceptable return on investment.

The following section outlines how some of these resources were deployed to do the projects that drove Cleveland’s redevelopment efforts.

City Government Programs

Mayor Michael White and his administration (1990-2002) were the main drivers of the city’s redevelopment agenda during the ’90s–for both downtown and the neighborhoods–and much depended on city resources and staff. White was an east-side councilman and state legislator who ran against his former mentor George Forbes, the powerful, autocratic head of City Council. The key to White’s election was an alliance with progressive white west side activists—Housing Court Judge Ray Pianka, Councilmen Jay Westbrook and Jim Rokakis, and Community activists like Chris Warren. After White’s election, Westbrook became City Council President and Warren Director of Community Development, adopting policies and practices that supported CDCs and their revitalization efforts and creating a more accessible and proactive city government. City actions and resources were essential to NPI’s strategy and programs, and vice versa. Together with a strong private-sector leadership commitment, the City’s support of CDCs and neighborhoods was exceptional.

Key to the City’s effective use of public resources for neighborhood renewal was the talent and commitment of a series of Community Development Directors beginning with Chris Warren and continuing with Terri Hamilton Brown, Linda Warren and Daryl Rush. All were committed to working with and for community-based developers, problem solvers rather than bureaucratic road blocks willing to make the extra effort. In addition to leadership at the top all relied on Bill Resseger to get worthy projects through the maze of City hall committees and myriad program requirements.

The White administration’s support for neighborhood projects included tax abatement on new construction, early Community Reinvestment Act challenges to local banks, and later, community benefit agreements, city investment of federal subsidy dollars in flexible and varied forms in many NPI projects, and council support for CDCs through a city-wide competitive operating support program.

To promote the building of single-family housing in Cleveland, the White administration provided the following: land at $IOO per buildable lot through the City Land Bank; 2) 100-percent, 15-year tax abatement; 3) $10,000, zero percent deferred second mortgages; and 4) access to capital for infrastructure and other improvements via the City Housing Trust Fund based on an annual competitive grant process. These program subsidies continued under the Jane Campbell and Frank Jackson administrations, augmented by a $65 MM public-private Neighborhood Transformation Initiative. The main source of the earlier neighborhood public investment support had been the annual federal CDBG allocation which declined significantly over the period reviewed.

Federal Urban Programs

Since the Reagan era, there has been a steady decline in resources and policies. During this period CDBG funding was reduced by 80 percent, and support for public housing decreased proportionately. In addition, cuts in welfare, food stamps and public housing budgets placed increased pressure on low-income communities. The War on Terror and major increases in military spending, balanced budget obsessions leading to tax-credit investment programming, and the sense that suburban/metropolitan strategies are more likely to gain support in the current political climate, have led to small-bore targeting of resources; these have been insufficient to transform poverty communities not seen as policy priorities.

The mix of federal programs of benefit to neighborhoods range from CDBG funding and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (through State of Ohio allocations) to the New Market Tax Credit for commercial/retail properties, the Nehemiah grant program, and the Community Development Finance Initiative of the US Treasury. Cleveland also received special-purpose funding from HUD in the form of a Supplemental Empowerment Zone, a Home Ownership Zone designation, and a HOPE VI public housing redo award.ome Home In addition, during the Great Recession, the Neighborhood Stabilization Program provided needed subsidy for reuse of abandoned properties like St. Lukes Hospital that were deemed “shovel ready,” and demolition funding for vacant foreclosed properties city wide. These federal programs were helpful but not transformative given the depth of the problems that they sought to address.

State of Ohio—LIHTC, Historic Tax Credit, Bond/lnfrastructure and Brownfields Remediation

This is a big topic, especially if one wants to explain the mechanics of how State resources get to Cleveland projects. Much of what goes on in terms of allocations is political and driven by relationships between the City and State cultivated by Low Income Housing and Historic Preservation interests, and it is beyond the scope of this narrative.

The basics are as follows: Many of the Cleveland neighborhood deals depended on tax-credit allocations, either through the Ohio Housing Finance Agency or state and federal historic credits. Awards were often made through a competitive application which the city needed to endorse and for which financing commitments and site control had to be in place. Cleveland fared well in the statewide competition, especially as relates to LIHTC awards. However, the complexity of the application process and the technical and financial requirements has meant that community-based organizations often lack the resources or ability to be competitive and as such rely on the Enterprise Foundation, the Cleveland Housing Network, and private real estate interests.

Few neighborhood projects were supported in the state’s biennial capital budget allocations, which went to downtown and major cultural institutions’ building projects. NPI was not at the table when Cleveland’s priority projects were identified.

Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority

Founded in 1937, CMHA was the first housing authority in the United States and for many years a leader in the field. CMHA has 10,000 units including 13 estates and 33 high rises. In addition, it administered both the Section 8 project-based and tenant-based voucher programs. It has 1000 employees and a $260 Million annual budget. Many of the estates are concentrated in the Central neighborhood of Cleveland and development of CMHA units outside this core has often met neighborhood opposition. The waiting list for both tenant vouchers and public housing units is quite long, indicating the shortage of affordable housing, especially for poverty populations. Funding for public housing, replacement units, and maintenance has steadily declined for thirty years. An exception has been the Hope VI program for replacement of older housing estates. Cleveland received two Hope VI awards and unlike Chicago’s demolition program elected to rebuild and retain units on site. CMHA’s Hope VI successful redevelopment of the Valley View Homes Estates in collaboration with Tremont West Development is a model for equitable development.

Banks, the Community Reinvestment Act, and Cleveland Tomorrow

Bank financing was and is critical in a weak market with limited public or foundation resources. The major banks and the White Administration negotiated community benefits agreements which outlined neighborhood investment goals, actions to be taken, and evaluation criteria for which the banks received high marks in their annual CRA review. Keeping the banks accountable and invested in neighborhoods was one of the White administration’s major achievements, though performance was uneven and the banks insisted that CRA findings were to be treated as trade secrets not share publicly with community and housing advocates

The CEOs of Key, National City, Charter One and Ohio Savings were on the board of NPI, and their banks financed neighborhood projects. Banks were also Low-income Housing Tax Credit investors. In addition, National City formed a development corporation that made equity investments in CDC market-rate projects, financing model homes and providing homebuyer mortgages. ShoreBank was also a vehicle for bank and foundation neighborhood investment under the local leadership of Charlie Rial. ShoreBank promoted a triple bottom-line approach that aligned bank profit with meeting credit needs of underserved markets while promoting green sustainable development as well. ShoreBank Advisory through the Glenville Enterprise Center attempted to support minority business start-ups. It had a significant impact on the community development culture of Cleveland, but less so on the real estate market.

Cleveland Development Advisors (CDA) was the real estate finance arm of Cleveland Tomorrow that supported shared corporate priorities. They initially invested in Village Capital and participated directly in larger neighborhood deals with collateral positions ahead of the city and Village Capital Corporation. While CDA’s primary focus was downtown development projects that did not involve CDCs, they did provide needed gap financing for larger, private-market neighborhood deals.

Foundations and Village Capital Corporation

Foundations were key players in funding nonprofits through operating grants, program-related investments, and direct project support. In Cleveland during this period, the foundations channeled much of their support for neighborhood development through NPI and its subsidiary Village Capital Corporation, which did the underwriting and lending on projects. (See descriptions of NPI and subsidiaries.)

NPI was able to target its efforts in high-impact ways, partly because of alternative public funding for CDCs in neighborhoods in which NPI was less centrally involved. The diversity and scale of funding available locally, while in some ways messy, made it easier for NPI to focus its resources and say no to CDCs and projects that did not align with its overall strategy and programs.

Collaborating was essential for Cleveland’s mid-sized foundation community to pool funding necessary to address the wide-ranging needs of a poverty population in a weak market city. Initially, the system benefited from the direct engagement of the Ford Foundation and the philanthropic commitment of BP America. Subsequently, Cleveland foundations worked with national funders through the National Community Development Initiative. NCDI came to Cleveland via LISC and Enterprise, which also provided national tax credit equity for low-income housing projects. The Enterprise Foundation remained in Cleveland and played a key role in supporting the Cleveland Housing Network, securing tax credit equity investments for low-income residents and permanent supportive housing for the homeless. Enterprise was and is a major player in state and federal policy advocacy for community development. Like NPI its role and priorities have evolved over time.

This collaborative funding strategy to provide gap financing worked well when market values and subsidy needs aligned, but less so when the subprime meltdown led to the housing market collapse and more resources were required to sustain the effort.

The Cleveland Housing Network

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit is the major resource to produce nongovernmental housing for poor people.

The Cleveland Housing Network (CHN) has evolved from its start as a network of 6 neighborhood CDCs renovating 50 vacant homes in its first year to a membership organization with over 100 partners operating in Detroit and other Midwest cities. Since its inception, CHN has developed over 6,000 housing units including LIHTC, Lease Purchase rehab, Homeward (new and rehabbed for-sale homes), and permanent supportive housing. In addition, CHN provides a range of services spanning counseling, financial literacy, weatherization, and the Family Stability Initiative. In 2010, working with NPI, the Enterprise Foundation, the city of Cleveland, and the Ohio Housing Finance Agency (OHFA), a plan was implemented to transfer 882 lease-purchase homes to current occupants with manageable debt levels. CHN is nationally recognized for the range and depth of its efforts to support housing for low-income residents. (See Krumholz and many others for description of CHN evolution.)

Much of the success, growth and impact of CHN is due in large part to the continued commitment and exemplary leadership of its four executive directors: Chris Warren, Mark McDermott, Rob Curry and Kevin Nowak. Each in their way has kept CHN in the forefront of affordable housing and supporting programs both locally and nationally.

New Village Corporation #NVC (Chapter 3 Neighborhood Progress Inc.: A New Approach to Community Renewal)

Private Sector Builders/ Developers

The CDCs and the city administration needed to attract qualified, mostly suburban builders to work in the city. To do so, projects had to make economic sense and address issues such as appraisal gaps, environmental contamination, and the city’s building and housing requirements and regulations.

A small cadre of mid-sized, family-owned housing developers emerged: Zaremba Homes, Marous Brothers Construction, Gordon Premier, Snavely Group, Ozanne Construction Company, Rysar Properties, Bradley Construction and Walter Burks. Occasionally, out-of-town developers such as the Finch Group and Pennrose Properties were recruited for larger projects.

In Cleveland, the Finast and Rego supermarket chains constructed stand-alone, suburban-quality stores in a few neighborhoods. The Saltzman family and its Dave’s Supermarket stores figured out how to deliver quality service in challenging locations. Peter Rubin and the Coral Company redeveloped the historic Shaker Square Town Center and the Eastside Market. Brothers Daniel and Patrick Conway and their Great Lakes Brewing Company were key to revitalizing the Ohio City Market, starting a trend toward food, arts and entertainment-based districts in more upscale areas that were attractive to suburban customers.

CDCs focused many of their efforts along key commercial corridors, focusing on façade improvements, merchant associations and promoting arts and entertainment districts: in Ohio City, the Waterloo District in Collinwood, along Professor Avenue in Tremont, and Larchmere in Buckeye Shaker, and the Gordon Square Arts District.

The larger local developers—Forest City, Jacobs, Carney—stayed downtown but still exerted significant political influence on allocation of public subsidy. The building trades unions were absent from neighborhood construction projects. In large part due to the Fannie Lewis law (Lewis was a Cleveland council person), contractors on larger neighborhood projects were required to hire a percentage of Cleveland residents. Note: The Ohio Supreme Court recently ruled that home rule does not apply in this situation after the State legislation’s pre-emption of Cleveland’s local hiring policy.

Other Resources

Cleveland Housing Court and Cleveland Land Bank

Cleveland is one of the few cities nationally that has both a Housing Court and a Land Bank. Without them the job of maintaining and redeveloping housing in the city would be much more difficult. Housing Court judge Ray Pianka and his staff were exceptional in their proactive neighborhood advocacy for code enforcement and tenants’ rights.

The Cleveland Restoration Society

Through its Heritage Homes Program CRS provided subsidized bank loans for historic properties in middle-market neighborhoods. It has been a key contributor to neighborhood stabilization in areas where NPl/CDCs are not major players as well as being an effective advocate for preserving Cleveland’s historic legacy.

Neighborhood Housing Services

NHS provided home improvement loans in stable neighborhoods, often in tandem with private bank lending.

Neighborhood Manufacturing Support

The City effort to support and attract small and mid-sized manufacturing and service business through business loans, infrastructure grants, city services and employee training programs relied heavily on the Cleveland Industrial Retention Initiative (CIRI), WIRE-NET (a nationally recognized operation on Cleveland’s west side) and Mid-Town Development. Each in their own way contributed to a viable neighborhood economy. As they were not directly linked to either NPI or the CDC strategy their achievements and issues are beyond the scope of this book.