Main Body

Chapter 1. Cleveland, Ohio, January 1970-71

“Immigrants get the job done” (Hamilton, the Musical)

First impressions of America – or maybe just Cleveland:

There are two which immediately come to mind from my first week:

1/ The huge, remarkable, shopping mall and train station beneath the Terminal Tower, for 34 years the second tallest building outside New York City.

2/ A street scene from, I think, the 2100 block of E18th Street looking towards the I-71 freeway. The sky is dark gray, the street is wet and slushy, incongruous telephone poles march along the roadside, snow is on the ground and piled up on the sidewalks so that the few hardy pedestrians are forced to walk in the road. It looks cold, ugly and miserable.

I can’t find that exact picture, but here’s an old one from Chester Ave that looks a bit like it.

I didn’t know about ‘overshoes’ before arriving in Cleveland.

This isn’t the image of America I had carried with me from Germany back to England and now to Cleveland (perhaps the most convoluted month of my life!). The image is of wide open farmland, a huge clear sky, a dead straight road lined by telephone poles and a song in the background: Wichita Lineman, by Glen Campbell

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxSarBcsKLU

Not exactly Cleveland, but hey, that was in the emigration dream. (Scores of years later it is still the cellphone ringtone of my cousin Roger’s son Paul, who IS a lineman – for a Devon, England, utility company). Nobody in Britain makes hit songs about Widnes, Ipswich, Manchester or even, really, London. Not as evocative as Campbell’s Phoenix or Galveston anyway.

Otherwise, over the first few months, I found Cleveland to be: Big. Wide. Friendly. Direct. Open-minded. Close-minded. Ethnic. Religious. Ignorant. Self-confident. Over-confident (doesn’t anybody do self-deprecation in a town like Cleveland?). Patriotic, Arrogant, Creative. Hard-working. Poor. Rich. Communal. International.

… Complicated. (I will have changed this list by 1976, and will at least have watched Rodney Dangerfield, the comedian who gets no respect).

Complicated because the United States of America takes up most of a continent, unlike little old Britain, which is so relatively small that when it is cold and raining it is cold and raining almost everywhere, including Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. But I don’t believe there is a single street in the US that compares to the medieval Shambles in York, my home town, which is so narrow people in the overhanging second-floor rooms can shake hands with the people on the second floor of the house opposite.

And in that sentence lies the first hazard a Brit journalist discovers on arriving in America: the language. In the UK the ground floor is the US first floor. The UK first floor is the U.S. second floor. Get that wrong and you could be HOURS waiting for your date to show up. Working in an American newspaper the Brit reporter quickly learns that: “You say tomayto and I say Tomaato” isn’t the half of it. Pronunciations are awful! What is this “rowt” word, when they mean “route” (root), as in a paper route? A “rowt” (rout) is when a body of people – usually an army- is defeated and runs away in panicked disorder. Does anyone sing: “Get your kicks on Rowt 66?” Grrr!

Years later my lovely, innocent, six-year-old son, newly arrived from England, would shock his teacher at an American kindergarten by asking her: “Have you got a rubber?” In England a rubber is something you use to rub things out on a page – not the other thing. But it made for much merriment in the staff room at coffee break that morning!

Here’s a better example of my problem:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UCo0hSFAWOc

It’s the attitude, you see.

“You wanna get that thing outta my driveway?” is not a crass American invitation to visit a neighbour’s driveway (kids today think it’s Transformers. Actually it’s Bill Cosby in his Noah sketch) in the way an English lady might say: “Would you like to come over for a cup of tea?” It is a no-fooling instruction. “Gimme a slice o’ ham, with a coupla eggs-over-easy on rye and hold the mayo,” is the American idea of a cafe order. On the other side of the pond the customer would be begging: “Please could I have a slice of ham with some scrambled eggs on a piece of bread? Please. And without mayonnaise, if you don’t mind? Thank you so much.” An English waitress getting a “Gimme a…” whatever from any customer might well produce….. a cold shoulder.

How rude!

Should Americans think of planning their first visit to England they could do worse than watch National Lampoon’s “European Vacation” movie (1986), in which the Griswold family fails utterly to escape the clutches of a central London traffic roundabout (sorry, traffic circle) and constantly crashes into an extraordinarily-polite Englishman (Monty Python’s Eric Idle) who can’t help but apologize whenever a Griswold accidentally runs over him. “No, no. It’s my fault!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bIOPVgnKUs

I first sensed there might be a linguistic mismatch between Yank and Brit when I was formally introduced to the staff of the Cleveland Press in the February, 1970, edition of “Who’s new at The Press”. It starts with a mug-shot of me alongside the words: “Peter Almond sounds like an Englishman because he bloody well is.” I don’t know who wrote that (possibly Bill Kjellstrand on the copy desk) but it’s a subtly inaccurate use of the word ‘bloody.’ An American might say that as a form of comradely humor (note I’ve dropped the English ‘u’, which I expect to do throughout the US section of this autobiography) but the average English person uses ‘bloody’ as a more vituperative sentiment, perhaps in a response to an allegation that he isn’t English: “He bloody well IS!”

Well, Clevelanders didn’t see a lot of Englishmen in the flesh, I guess, so the image runs ahead of the real thing. To put it another way, I had been expected to arrive at the Press months earlier, and I don’t think anybody had any idea what I looked like or sounded like and-for some of the women – how ‘available’ I might be. Months later I heard that because I had gone off to the army in Germany and would be getting my US visa there I was some sort of James Bond. Joke, surely. But I’m not sure I ever did tell Dick Campbell I was getting married in England just short of two weeks before my departure for the U.S. In those first two weeks in Cleveland, before Anna arrived, I must have appeared to be an “available batchelor” to some of the female members of staff. At least, I suddenly discovered that what I had heard about ‘forward’ or ‘aggressive’ young American women was true. I did get more interest from some women than I was used to.

Maybe this is the right time to mention Short Vincent and Roxy.

Short Vincent was not a sidekick of gangster Shondor Birns, who hung out at the Theatrical Grill, but a small street between E4th Str and E6th, which was arguably the center of Cleveland’s nightlife. And Roxy wasn’t the name of an old stripper (although I reckon its not a bad name for an old stripper) but the Roxy Theater, a burlesque house which featured semi-naked dancing girls (nothing showing below the waist please, ladies!). There, for a modest entry fee, you could ogle strippers, listen to music and watch comedians (in its heyday including such people as Abbott and Costello and Phil Silvers) deliver dirty jokes and talk about ‘Nessul bars’ (Nestle milk chocolate). After which you could indulge a foot-long hot dog next door at the Coney Island restaurant.

I went to the Roxy one lunchtime with half a dozen Press reporters to see Chesty Morgan, the girl with the ‘world’s biggest boobs.’ Her real name was Liliana Wilczkowska and with a name like that could easily have come from Cleveland. But she was born near Warsaw, Poland, raised on an Israeli kibbutz and moved to New York in the 50s. She married a man who was killed in a robbery in Brooklyn, made several movies featuring her apparently-natural ‘73-inch bust’ – including an appearance in Fellini’s movie Casanova – and toured the country’s burlesque joints. She later married National League baseball umpire Dick Stelio.

I thought at the time it was all wonderfully sleazy, classically American and publicly open and contradictory – unlike the dirty-raincoat, peep-show dives of London’s Soho. Across the street at Superior and E9th Str was the St John the Evangelist Cathedral, the focal point of Cleveland’s Catholics, barely a two-minute walk from Short Vincent’s boozing, gambling and ogling. The cops tolerated it. The politicians tolerated it, and so did the public. It was a meeting ground for all, rubbing shoulders with the likes of notorious ‘Mushy’ Wexler, and almost certainly the Press’ great crime reporter Bus Bergen.

The Roxy closed in 1972, reopened as an X-rated cinema a year later and was torn down along with a number of other buildings in 1977. In its place rose the huge new international National City Bank building (now the PNC Bank Building). Shame.

So, back to the ordinary facts.

Bill Tanner, the City Editor, has just read through my first edition copy about a man being killed in a fight the night before. My story lacks color and information about both the victim and the man accused of killing him, who is now in jail. And it says nothing about the legal process. I’m at a loss to quickly identity resources to enhance the story.

“Call the judge,” says Tanner. “I’ll give you his home number.”

Call the…..WHAT? The JUDGE? At his HOME? I have never heard such a thing! The official residence for a high court judge who would sit on a murder case in York, England, is a high-walled, secure 18th century mansion near Lendal Bridge. He leaves this building for court each day in an official limousine wearing his full ermine-fringed cloak and wig, and under police escort he is driven to the court house next to the remains of an 11th Century stone tower, where 150 Jews were trapped by a mob and either committed suicide or were murdered in 1190. He must never be stopped by any member of the public, and never, ever, speaks to the press. And certainly not about current cases.

I am quickly learning that judges in the US are elected by the public, not by the Queen on the recommendation of the Lord Chancellor.

“Oh, I’ll do it,” says Tanner. “He’ll be up by now. I’ll see if he’s got the guy’s phone number.”

Tanner was the main reporter for the Cleveland Press in the 1954 first trial of Dr Sam Sheppard, an osteopath from suburban Bay Village, for the brutal murder of his wife, Marilyn. It was a sensational case, with all the tabloid elements of money, power, politics and sex that filled the front pages of all the local newspapers at the time. The Press was singled out for strong criticism, following headlines such as “Why isn’t Sam Sheppard in jail?” and “Quit Stalling – Bring him in!” (written personally by editor Louis B. Seltzer). Sheppard strongly protested his innocence, but was found guilty and spent ten years in jail. In 1966 the US Supreme Court set aside his conviction, citing “inherently prejudicial publicity” which everyone took to mean ”primarily the Cleveland Press”. This time Sheppard went to a retrial with the country’s most famous lawyer, F. Lee Bailey, by his side. Again he was freed, became a wrestler, and died in 1970, just after I arrived.

So, Tanner was a well-connected reporter-editor, who was to become a significant influence on my career, and he was showing me how crime reporting was done. I took the phone number of the victim from him, dialled and found myself talking to the murdered man’s widow. She had not slept and was very tearful.

She heard my accent and asked if I was from England. I said ‘yes,’ and she burst into tears again. “Oh, my husband so loved England!” she sobbed. “He was there during the war!” She kept talking about England, and all I could think of as deadline approached was Stan Freberg, the American comedian whose FBI Dragnet spoof included the deadpan words: “The facts, ma’am. Just give me the facts.” (Much later actor Jack Webb, alias Joe Friday, insisted he never actually said that).

I determined there and then I needed to develop an American accent and adopt “Just gimme the facts, ma’am” as my modus operandi from now on.

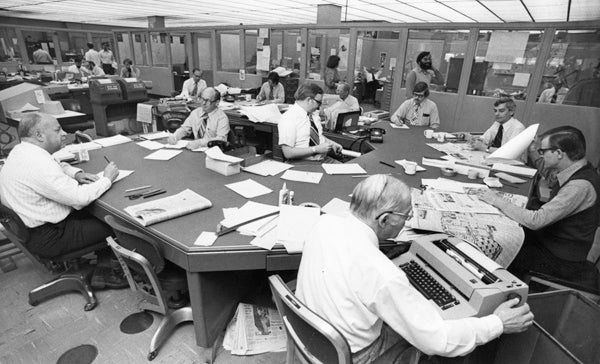

It is strange to look at photos of the Cleveland Press newsroom 50 years later: large, open plan, scores of desks, lots of men in white shirts and somber neckties, the women in smart casuals. And not a single computer screen in sight. The biggest boon to me at the time was electric typewriters (we were still using clunky Imperials in England) and properly prepared letter-size sheets of paper with double carbon copies, not cheapo backs of color advertisements I’d been used to. And superior, easy-glide metal filing cabinets, with properly-arranged clippings library. Luxury!

At the time The Press was the flagship of The Scripps- Howard newspaper chain, and hosted American Newspaper Guild Local No 1, the first of its kind in the country. I was already a “fraternal” member of the National Union of Journalists in England so it was an easy international transition into what was otherwise a “union shop”. But because I was later arriving in Cleveland than expected, Dick Campbell’s 1969 wage offer to me was out of date, and I walked into a little “debate” over what level my salary should be set. It was nothing personal, but management and the union had already compressed the number of years work a journalist needed to reach the minimum top grade. Lawyers did get involved, but Dick told me directly the settlement wouldn’t affect my career there.

Whew! I wasn’t ready to have to start looking for another job.

Monday, Jan 26, Diary says I heard from Anna, and she’s coming on Sunday! Yippee! How will she do? She’s never been on a plane before. Maybe she will come in that new Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet that had its first commercial flight from New York to London four days ago, with 335 passengers? Wow. It has to go back to New York, doesn’t it? I see I wrote a feature for the Community Page, which covers everything local in Cleveland that isn’t covered by everybody else. Tony Natale, another reporter who had a lovely sensibility, invited me to dinner at his house in Shaker Height. His wife, Gail, continued to help with our tax and legal affairs.

Two days later I moved out of Al Horton’s place via dinner with Bill Tanner for the both of us. I can’t get over just how friendly everybody is at The Press. I moved into an apartment on the ninth floor of the Regency House on East Ninth Street, barely 100 yards from the office.

Sat, Jan 31, I went to Cleveland Hopkins Airport to meet Anna off her plane from London via New York (no, it wasn’t a Boeing 747). She was exhausted and emotional. We stood in our new flat – our new home – and both cried, arms wrapped around each other.

NOW we will start our lives together, the American way – leaving our families 3,750 miles away across an ocean.

The Community Page of the Cleveland Press does not exist as such in Britain. It’s a collection of community news in the city of Cleveland and suburban Newburgh Heights, not quite the suburbs page – which covered more than 60 suburbs in Cuyahoga and surrounding counties. The Community Page editor was Marge Banks, who was finding her way around as an editor just as I was as a Cleveland Press reporter. She looked and sounded just like my sister– except she was black, had frizzier hair than my sister and spoke with an American accent. (Actually, she came from New York and had a good education).

She was, indeed, one of the few, one of the very, very few non-white faces in The Cleveland Press newsroom. There were, to my memory, just two or three others amongst a news staff of more than a hundred: Hil Black, chief police reporter; Van Dillard, a photographer; Bob Williams, formerly a veteran editor for the even-more local Call and Post weekly who covered the black East Side; and Elaine Lemon, a lady who filed our stories in the library. It didn’t matter a jot to me, but I would soon find out exactly what racial issues did mean in Cleveland, Ohio.

The first directly-racial thing in the office I encountered was about April 1970, when the shout of “Boy!” from the copy desk came to an abrupt end. “Boy” was the traditional newspaper way of summoning a runner – usually a teenager – to take copy and messages from the copy desk to the printers. But in the late 1960s and 70s, when blacks were rioting in the streets demanding respect, any white person calling any black person a ‘boy’ was not good. Somebody at The Press made a complaint. From 1970 onwards the “Boy!” died, and the cry “Copy!” was born.

Anna and I have been invited by Hilbert and Judy Black to join them at a showing of the recent movie Putney Swope, at a cinema near University Circle. Hil doesn’t know what the movie is about but has the idea it is entertaining, educational about the modern black experience in the widest sense for white immigrants like us.

We enjoy it. He and Judy clearly do not. For a start we are the only white people in the packed theatre. Not that we are bothered, but we notice that people do keep turning around and looking at us. Some give us sideways glances just to see what our reaction is at various points. Others stare with what I would later accept is an expression of: “This is our theatre. What are you doing here?”

The story, essentially, is about an advertising company whose chairman dies and the board must find someone to replace him. All but one are white except Putney Swope, hired as a token black executive, who gets the job because all the board members hate each other and vote for him thinking no-one else will. Swope makes major changes, such as firing all the white staff except one and refusing to advertise harmful products.

Hil and Judy are mortified by all this, and cannot stop apologizing afterwards. We are not at all offended, and loveable though Hil and Judy are, we realize they are of a gentler time and place. We read years later that Putney Swope would be recognized as the precursor of an era of “blacksploitation movies”, and that in some black neighborhoods Hil and Judy might be known as ‘Oreos,’ ie as in the cookie: black on the outside, white on the inside.

Maybe it is because I am a very new, but original, white descendant from the old colonial masters who brought black slaves to the New World, but I find this reprehensible. I will discover much more about race relations in the months to come.

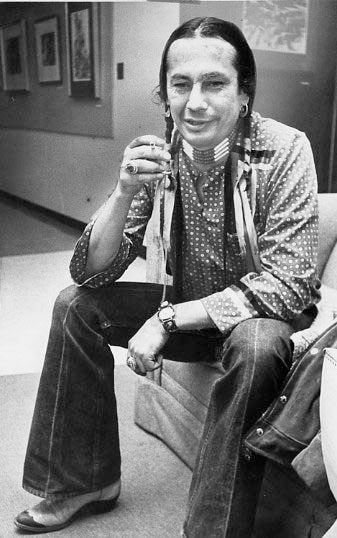

But one of my first stories for the Community page, I recall, was not about the large black community. It was about the status of American Indians, whose Cleveland centre was in the basement of a church on Lorain Ave, on the near West Side. As good a place to start understanding Cuyahoga County and its 1,721,300 people as any. Indians – or should I say Native Americans – were obviously the original occupants of America. Indeed, the word Cuyahoga is Iroquois for “jawbone”, near the mouth of which would be built the city’s great steel mills. I had never met a Red Indian before, and my first sight of the head of the Indian center, Russell Means, was a wonderful experience: a handsome, strong, tanned face straight out of the cowboy movies of my childhood!

He and his colleague Dennis Banks were founders of the American Indian Movement from that center, and Means was its increasingly-active director against the backdrop of the American Civil Rights Movement. I can’t remember what my anodyne story was about, but Means the Magnificent (my expression) was never likely to be forgotten, not likely because he kept popping up all over the country for the next few decades. I remember him complaining to me about Chief Wahoo, the cartoon mascot of Cleveland’s baseball team, the Cleveland Indians, whose toothy face beamed out over the city from the Municipal stadium. He failed to get it removed. (In 2021 the name was changed to Cleveland Guardians, and Chief Wahoo replaced by the letter C).

Means and fellow Indians took over a replica of the original Mayflower in Boston Harbor to protest government policies towards Indians, followed in 1972 by leading hundreds of Indians into a 71-day siege at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. That made the government take serious notice, not only because three people were seriously wounded, including an FBI agent, in the hundreds of shots that were fired but it was a reminder to the nation that since 350 Lakota men, women and children were massacred there by Union soldiers in 1890 the situation of Native Americans had not kept pace with the rest of society.

Plenty more happened to Means over the years, including being shot several times, appearing in long court battles and in numerous movies, perhaps the most famous of which was Last of the Mohicans, the 1992 epic movie in which he and Daniel Day-Lewis starred as Indian and Englishman living together in 1757 during the French and Indian wars. (the North American part of the larger Anglo-French Seven Years War). I could go on about this period of history because the economic and security consequences of this expensive global war were that Britain didn’t have much money when colonial upstarts in America started the War of Independence six years later. Americans already had more self-governance and freedom over the previous 150 years than England itself, so what was a couple of extra taxes on the colonists to maintain a standing army of redcoats for their own security?

The Yanks won, they tell me (Ha! Sneakily helped by the French fleet!), and the Appalachian Mountains were no longer the western frontier of the 13 colonies. Originally part of French Canada, the land south of Lake Erie was ceded to Britain in 1763 and after the War of Independence it became known as Connecticut’s ‘Western Reserve’ 63 per cent of which was water: ie Lake Erie. The first white man to survey the land at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River was retired General Moses Cleaveland who, guided from Buffalo by a black trapper. kept the Iroquois quiet with $1500 in cash (about $26.000 in 2020), two beef cattle, 100 gallons of whisky and an assurance that the settlers would not go west of the Cuyahoga River. They did, of course. Cleaveland went home right after his survey and never returned. Despite that his statue still stands prominently in Public Square.

But why the name change to Cleveland?

As one whose journalism career started in a part of northern England next to the Cleveland Hills, I’ve often wondered if Cleaveland’s early settlers had any link to the motherland. Water, ports, railroads, coal and iron ore were part of each area’s histories. England’s Cleveland was always spelt without the first ‘a’, so is this the reason the American Cleavelanders followed the English spelling when their town started to grow?

There is no evidence of it, and the likely explanation is disappointingly-mundane: in 1831 the new local newspaper, the Cleveland Advertiser, couldn’t get those words to fit onto its masthead. They dropped the ‘a’ and then it fitted.

Makes sense to me. “All the News that fits in print!” to misquote the original cry of the newspaper vendors.

Thus does the local paper set a city’s standards for all eternity!

Back to the 1790s (if not the 1970s) ….

Lorenzo Carter, the first permanent settler, built a large log cabin for himself that had a large attic for the storage of fur pelts, which he apparently traded. He got drunk a lot but was, by all accounts, a big man and a better shot with a musket than the Indians. He shot one dead when two Indians he had punished for breaking into his warehouse and stealing his whisky tried to ambush him. The other got away.

Perhaps more significantly, since we are discussing Indians, the city’s first – and most famous – public execution was of an Indian: John O’Mic (apparently without the ‘k’ but what else would a white man call a native whose name probably sounded a bit Irish?) in 1812. According to veteran Cleveland Press columnist Julian Krawcheck – a fine, Southern gentleman who was among the first Press staff to invite Anna and me to dinner – O’Mic was convicted of killing two white trappers and stealing their fur. In the absence of a jail at that time he was held in Lorenzo Carter’s attic and then brought out to face his death by hanging.

Krawcheck wrote a piece about O’Mic’s execution in a souvenir section of the Press on July 20, 1971, to mark the 175th anniversary of the city (I still have a yellowing copy of the whole multi-page section). O’Mick, he wrote (he used the ‘k’), had his face painted in traditional tribal fashion, and wore tribal attire to show how brave an Indian was in the face of certain death. He rode atop his coffin to the site of the gallows. A black mask was put over his face by Sheriff Samuel Baldwin, and at the sound of a drum roll a prayer was said and then the crowd waited quietly. As Baldwin moved to pull the handle of the trap door O’Mic suddenly lurched sideways and hung onto a side support of the gallows as if his life depended on it. Which it did, of course. Why his hands were not bound, wrote Krawcheck, is unknown, “but it may be assumed that it was a gesture of courtesy to a ‘brave Indian’.

Baldwin was unable to pry O’Mic’s fingers from the post, so Lorenzo Carter stepped forward to remind O’Mic of his promise to “die bravely.” To encourage him, Carter produced a pint bottle of whisky from a nearby distillery. O’Mic downed the sprits, but still hung on. Wrote Krawcheck: “Carter produced a second bottle of whisky and handed it to the Indian. Lorenzo must have winked a signal to the sheriff, for while O’Mic was busy gulping, Baldwin sprang the trap. The resulting jerk broke the Indian’s neck, and the rope.”

O’Mic’s body was quickly buried under the scaffold, but the next morning it could not be found. “Apparently, the area’s budding medical community had conspired with Sheriff Baldwin to appropriate the cadaver for co-operative medical reports,’ wrote Krawcheck. Another story is that his skeleton was used for years by Cleveland physicians to teach medical students. Or that one Doctor Town, of Hudson, Ohio, kept it in his office for the next 40 years and said it was O’Mic’s.

Or perhaps it came back in the form of Russell Means…… ?.

What this story says to me was:

(1) Cleveland should probably have been named after Lorenzo Carter. Carterville, maybe. But not Cleveland.

(2) White settlers took huge advantage of native Americans’ genetic intolerance of alcohol and took decades to understand and accommodate them.

(3) Cleveland’s reputation as one of the best medical centers in the world could perhaps be traced back to John o’Mic’s body.

(4) Cleveland’s earliest activities predicted a rough, tough future that would be exaggerated by the arrival of steel a few years later.

(5) Crime would be a central by-product of the city’s expansion

(6) It would create an ameliorating need for a high civic culture, as expressed by the medical facilities of Case Western Reserve University and Cleveland Clinic, and by the Cleveland Orchestra, the Cleveland Playhouse and the Cleveland Public Library.

What got Cleveland really growing in the mid 1850’s, of course, was steel. Or rather iron, from ore discovered in the Marquette region of Minnesota (later called Cleveland Mountain) by Clevelander Dr. J. Lang Cassels in 1845. Within ten years ships were hauling the ore to the harbours of lake Erie and on to the Mahoning Valley, where Youngstown hosted the region’s first blast furnaces.

I’m quoting here directly from a series I wrote about Cleveland Steel industry in The Press in 1981, 11 years after my arrival in Cleveland. Steel was at the heart of Cleveland’s history, and steel was the reason for most of the ethnic communities of the city (after the Indians and the early Anglo settlers). By 1981 the steel industry in northern Ohio was becoming known as “The Rust Belt”, and as I was the one directed by The Press to research it I guess I could claim to be “Ohio’s Newspaper Expert on the History of the Cleveland Steel Industry” – For 1981 anyway.

Anna and I have taken the Rapid from the Terminal Tower to Shaker Heights along its entire length, just to see where it goes. Walking around the square we see a place called The King’s Pub and, naturally as subjects of the King (or at least Queen), we go in.

“Two pints of beer, please,” I ask the barman.

“ID”. He replies.

“What?” say I.

“ID. I can’t serve you till you prove your age.”

We are puzzled. What is this ID? Are we in Germany circa 1943? “Vehr are your peppers?” I know the minimum age to drink alcohol in America is 21, but I’m 24 and Anna is 22, and I’ve been drinking alcohol legally for six years (at least).

Passport? Driving licence? Student ID? The barman demands. We didn’t think it necessary to have to carry these just to get a beer in America. So we leave in a huff. Maybe we just don’t LOOK old enough, and the barman thinks he must have proof. (It must be said, though, that days earlier a 21-year-old mental patient blew up the Shaker Heights Municipal Building, including its police station, killing himself and injuring 14 others. Perhaps the barman was just nervous of strangers)

But we remember it because it was our first of many experience of a bureaucratic, legalistic way of life that reaches deep into the heart of America, compared to what we have known.

“We’re not in Kansas any more,” as Dorothy might have said.

With iron ore coming down from Lake Superior, coal going up from the Pittsburgh area and Cleveland at the apex of two railroad funnels, the city developed many small iron companies to make railroad equipment. In 1859 John D Rockefeller brought oil from newly-discovered wells at Titusville, Pennsylvania, and in 1868 Englishman Henry Bessemer’s new steel-making process was put to work in the Cleveland Rolling Mill in Newburgh, on the southern edge of the city. Andrew Carnegie knocked his competition flat in 1875 with his famous J. Edgar Thomson steel works in Pittsburgh, but the Cleveland docks provided plenty of incentive for engineering. The Globe Iron Works built the first steel ore ships in 1882, and Wellman Engineering pioneered another English invention – C.W. Siemens’ open-hearth process – in the city.

The year 1882 was not quite the runaway success the steel bosses had assumed, however. Skilled Scots and Irish workers, members of the new Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, went on strike for $12 for a 12-hour day, six days a week. Bad timing, and as I wrote in my series: “This was the age of vast European immigrations, and mill owner Henry Chisholm promptly went to the docks of New York City, offered $1.50 a day and brought some 1,500 Polish and Bohemian (Czechs) workers back to Cleveland” to replace the Scots and Irish. Later, Mill owner Amasa Stone dropped anchor in his motor yacht at Gdansk (Danzig) in Poland, advertised for labor to go to America and brought another few hundred Poles to Cleveland via cattle boat.

Three years later, in 1885, the Poles and Czechs had also had enough. Their strike led to the first major confrontation between strikers and the police, many of whom were the same Irishmen the Eastern Europeans had replaced. Groups of Poles and Czechs marched through the city, closing down related industries and sometimes carrying a red flag. The local press branded the strikers as drunkards and cowards. The stigma lasted many years and deepened in 1901 when Leon Czolgosz, a mentally-unbalanced Pole from the Warszawa section of Cleveland, assassinated President William McKinley in Buffalo, New York.

The Poles of Cleveland stood on the defensive, clinging to their communities as the general community regarded them as a hotbed of troublemakers. Their numbers made them stand out, especially from 1900 to 1920, when the Polish population of Cleveland and neighbouring Berea stood at 35,000, most of them straight off the boat, and joined by family members who spoke little English and had little idea where they were. Warszawa was the largest of the Polish communities (the other was the Poznan community of Prussian Poles, around Superior Ave and E 79th St.). They looked inwards and to the Catholic Church, helped immensely by Father Anton Kolaszewski, who personally saw to the construction of St Stanislaus Church. It was completed in 1890, second only in size to St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York.

The Scots, Welsh and Irish built homes close to the Rolling Mill and assimilated into Ohio society across greater Cleveland, with some Irish later moving to the Collinwood area of the far east side.

Maybe it’s because – as a ten-year-old – my first girlfriend was Vanda Gustowski, born in England to émigré Polish parents; maybe it was because the Poles fought for us after their country was overrun by the Germans in World War II, or because their pilots were righteously more aggressive than the RAF in shooting down Nazi planes in the Battle of Britain, or because the Russians took over their country and wouldn’t leave. Whatever; the fate of bashed- about Poland as a free, independent nation seems to have struck a chord in me that wants to dance the Beer Barrel Polka or munch on a pierogi.

Economically and culturally held down by the rest of American society, the Poles of Cleveland devoted much emotion and effort to events in their homeland, first in the First World War when Germany attacked it, and later when Russia invaded and held it. But the Cleveland Poles were riven by dissension. Those in the Warszawa and Poznan districts of Cleveland – mostly Prussian Poles – wanted a completely independent Polish state. The Austrian and Russian Poles, who were centered across the Cuyahoga River in the Tremont Kantowa District of the city, wanted a satellite Poland under Austrian or German government.

World War 1 galvanized Poles across the US into direct action. They formed the Sokol Polski, the Polish Falcons, with Nest 141 being the Cleveland section. It was ostensibly a gymnastic organization, but from here they also recruited soldiers for the US Army going to France and, it is said, raised funds for arms to help train potential Polish soldiers. They joined up as full Polish units, and their key political figure was not President Woodrow Wilson but General Joseph Pilsudski, who first led Polish brigades with the Germans, then was jailed by them, then defeated the Bolshevik Russians at the Vistula River in 1920. For a brief two or three years Poland was a free and independent country. Then Gen. Pulsudski returned to power in 1925, and became Poland’s virtual dictator.

The Poles of Cleveland could never agree about him. In 1930, when one of Pilsudski’s generals planned a visit to Cleveland to take part in a tenth anniversary celebration of the Vistula battle, the Kantowa faction wanted to hold a field mass for 40,000 people to mark it as a great socialist victory, but the Warszawa faction wanted to mark only the ‘the miracle of Vistula,’ with no great tribute to Pilsudski. Because of continuous bickering the mass was cancelled. The Great Depression that same year hit Cleveland Poles hard. Unlike much of the rest of the country they didn’t move to seek work. Coming from a country which never had private housing they had poured their wages and life savings into property, proper homes of their own, even if they were multi-family dwellings. Great in good times, but in bad they couldn’t sell him, except at a loss, and they couldn’t get mortgages anyway.

I’ve gone into this history in some detail because there were echoes of it in all the ethnic communities of the city. And because in one of the largest ethnic groups I found the seeds of some great story lines, both real and fictional.

One of the latter became my first novel in 1996. It was called The Moscow Option and is unpublished because the fiction-writing coach I hired to be brutally honest with my writing did just that. “Great plot, not enough character,” she said. One day I’ll get round to rewriting it. (The story line is of fictional F-15E pilot David Kopanski, based in the UK, who discovers his father and grandfather were so caught up with the Polish cause during and immediately after WWII that his father joined a plot to drop a nuclear bomb on Moscow. The bombers’ crashed plane is discovered in 1996 and then the drama really starts. Fanciful? Perhaps, but not if you read the histories of General George S. Patton and USAF General Curtis le May).

As I discovered in writing for the Cleveland Press not every American immigrant found the American Dream, and Kopanski Senior – the grandfather in my novel – was one of them. I’ve imagined him arriving from Poland in 1930, taking a job from laid-off Irish workers at the Newburgh rolling mill, and being assaulted and badly injured by them – just as happened 50 years before. He never worked again, but poured the emotional energy he still had into his local community, doing odd jobs, singing Polish songs, reading Polish newspapers – and teaching his son Jacob to be Polish first, American second. At 18 Jacob was just the right age to join the Army Air Corps, where he discovered other Poles who vowed revenge for the 1943 Soviet murder of 5,000 Polish officers in the Katyn Forest, near Smolensk.

One day I’ll get the novel published, and you’ll find out yourself why World War III could have almost happened. But, for the moment, I’ll just leave it as a possibility for the tourist trail in what is now known as Slavic Village, Cleveland, Ohio.

“Downtown Living Can Be Rather Nice,” says the headline of a personal story I wrote for the Community page. “Our English reporter, three months away from his homeland, gossips about living in the heart of Cleveland.”

Here’s a flavour:

“Put up your hands all of you who have walked down the Mall, winter or summer, on a Sunday afternoon, not going anywhere mind you, just strolling. And hands up all of you who have never cursed over having to wait for buses to take you to the nearest department store. …..

“Have you ever realized just what an incredible sight it is – looking across Lake Erie from the Mall? Call it a man-made jungle if you like, but there can be few places in America where almost every conceivable form of transportation can be seen: railroads, a freeway, liners, an airport, freighters, passenger boats, a submarine, trucks, cars, buses, cargo planes, old fighter planes, executive planes. You name them – they’re all there.

“My wife and I took a walk that way last Sunday afternoon. It was cool. Rain was threatening but the wind was fresh and straight from the lake. We went down to the dock front to see the second ship of the season arrive.

“We weren’t the only ones there. Scores of people watched too. But from their cars. Not one as much as put a foot outside their cars…..”

I admitted Downtown ‘is not the place I would go for an aimless stroll at 10 at night.’ And that “The night after our splendid walk down to the dock front we heard the sound of wailing police cars; teenagers leaving the Temptations concert at Public Hall had gone on a rampage.”

Not that robberies were any the less likely during the daytime. A few days later I wrote: “Police statistics for the first 14 days of this month indicated you are more likely to be assaulted and robbed walking on the city streets during daylight than at night. And the majority of victims are women.” Police Chief Lewis Coffey told me the reason most armed robberies were against men at night was because they were in the ‘wrong place at the wrong time’, often inviting crime by driving around certain sections looking for women, or getting drunk in bars. The women during the daytime mostly had their purses snatched and stolen whilst shopping. Surprise, surprise.

Fifty years later I turned over the cut-up, yellowing part of the page where my story played and saw that the movies “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Bullitt” were playing at three suburban cinemas; “Anne of the Thousand Days” starring Richard Burton was showing somewhere else, the Central News of Toronto (?) was presenting a concert and dancing “featuring popular stars of folk music from Yugoslavia at the Slovenian National Home at 6417 St Clair Ave,” and the “Travelling Burlesque Roxy Theater’, at 9th and Chester had Sherry Christie on stage (pic of her in a bikini) for four shows between 1 and 10pm.

Variety, they say, is the spice of Life.

Actually, our time on E.9th St. was coming to an end. Now with a Mustang convertible we couldn’t afford the cost of downtown parking, and had to leave it in a low-grade garage some distance away. As we packed up to move to an apartment on E. 148th St., Anna regretted no longer being able to shop at the outdoor market near the Terminal Tower.

…. And saying goodbye to the “nice, friendly young ladies” she met on the stairs and elevators of Regency House. By then I think she had figured out for herself that they were renting their flats by the week, by the day – perhaps even by the hour!

E.148th Street wasn’t so great. The house we rented was quite well furnished, but when we found Silverfish bugs creeping out of our kitchen sink we decided it was too damp for us. In the month that we had to close our tenancy we did make one little friend, though: a yellow and green budgerigar, an Australian parakeet. We called it Dickie Bird, or Dickie for short. What else? We started teaching him to talk: simple things, like ‘Cup of tea,” and let him fly around the room – windows shut, of course -as well as perch on my eyeglasses (refer back to Michael Macintye YouTube clip) and peer at me upside down.

While Anna was getting her life sorted out by taking a driving test in nearby Richmond Heights (“Don’t you worry ‘bout a thing, ma’am,” said the police officer instructor, shifting his revolver around in order to get into the front passenger seat of the Mustang). Then travelling down to Columbus to sort out her education and nursing qualifications while I was learning the ropes of the morning rush hour along I-90, the Lakeshore freeway into downtown Cleveland. It was easy enough, I guess. The Municipal parking lot was right next to the Press building at 9th and Lakeside (no discount for us. We paid the full 50c a day. In the winter it was bitterly cold, the wind whipping hard off the frozen Lake Erie).

Even here on the eastern edge of suburbia we continued to have ethnic company not far away. Up the road were small Irish and Italian communities near Collinwood High School. The former was mixed with the latter for one Irishman, Danny Greene, a criminal who worked against and with the Cleveland mafia through the early 70s, having his home blown up half a mile from us in 1972, and then killed by a bomb in nearby suburban Lyndhurst in 1977. A movie based on his criminal career, Kill the Irishman, was released in 2011. Greene is not to be confused with another mobster Irishman, Frank Sheeran, about whom a bigger Godfather-type movie, The Irishman, was released in 2019. It is set mostly in New York City. I’ll come back to the mob later.

As an ethnic community the Irish were almost completely assimilated into the American mainstream, forming their own personal links through their professions: notably the police, civil service, law and business. I once brought a copy of Leon Uris’ book ‘Trinity’ into the office to show our politics (City Hall) writer Brent Larkin. The book is about The Troubles – Catholic vs Protestant, nationalist vs unionist – whose fictional hero is an Irishman called Larkin. I was taken aback when Brent said he had not realized Larkin was an Irish name, so deep had the assimilation become over generations. There were plenty of Larkins in England too who didn’t know the name was Irish. Cleveland’s Irish certainly knew how to throw a party and a parade, though, especially around St Patrick’s Day when the beer flowed green. Memories linger long in the Irish soul, however, and I think I got, shall we say, a “cool reception” when I was introduced to one deeply-Irish group or another as an Englishman. The year 1969 was the beginning of serious sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, the start of The Troubles, and for the most part Cleveland’s old Irish knew which side they were on. It would not have been a good idea to tell our new Irish-American friends that I had been working for the British Army at that time. In the early 70s in America the IRA – and old IRA songs – were never far away.

Memory Flash: Sunday April 12, 1970, the penultimate entry in my six-year-old diary. I don’t know why it stopped.

“It’s a LUVLY DAY,” I’ve written in capitals, and we are going for our first long tour of Ohio. The light green Mustang has been polished, its top is down, and we’ve got a picnic lunch. Down I-77 to Akron center for a quick look around, then to Canton, noting the location of the National Football League Hall of Fame. New Philadelphia next. We stop for lunch at Lake Tappan, on Rt 250 near Deersville, then on to East Liverpool and Weirton, whose steel mills we later recognize as locations for parts of the Vietnam War movie’ The Deerhunter. Then back to Cleveland; 300 miles in all.

“Cor. What a BIG country” I wrote. And we hadn’t seen Texas yet!

When we moved again that summer it was just for a few blocks closer to Euclid, a suburb where Anna had her first full-time job as a nurse at Euclid General Hospital. Our ground floor apartment was at 17745 Lakeshore Blvd, in a modern three-storey block of six apartments. We were excited about it, only a block away from Euclid Beach amusement park. We had seen the grand entrance, and a glimpse of what appeared to be a roller coaster. What we didn’t know was that Euclid Beach, opened in 1895, had closed permanently only a few months earlier. For daily excitement we would have to depend on the World War II stories of Julius Janulis, custodian of our apartment building, who would often – at least with me – appear near the back door to regale me with tales of when he was a Lithuanian Freedom Fighter, blowing up first German troop trains and then Russian ones. I believe he was secretary of a local group of Lithuanian exiles.

The end of World War II had brought a lot of East Europeans and Germans to America, not only those such as Werner von Braun whose rocket building skills set the US on the route to the moon but at least one who allegedly hid very dark backgrounds, which they would not discuss. One such was John Demjanjuk, a Ukrainian who served in the Soviet Army and was captured by the invading Germans in 1942. They sent him to work as one of their guards at the Treblinka death camp in Poland, where nearly 900,000 Jews were exterminated. He made his way to Seven Hills, a south Cleveland suburb in 1952, settled into the Ukrainian community there, worked at the Ford auto factory in nearby Brook Park, and would have stayed there had US federal officials not received an Israeli warning in 1977 that he had been identified as ‘Ivan Grozny’ – Ivan the Terrible – who mutilated naked Jews as he pushed them into the gas chamber at Treblinka.

The case became an international horror story of trials: in Cleveland, Israel, and Germany, of identifications and misidentifications, much of it highly emotional, as elderly Holocaust survivors in court relived their terrible memories, sometimes mistakenly.

I was in Cleveland when Federal Judge Frank J. Battisti (much more about him later) ordered Demjanjuk to be stripped of his adopted US nationality in 1981, and extradited him to Israel. But I have at least observed some of the silent rectitude of the estimated 35,000 Ukrainians who lived around St Josaphat Byzantine Church and Demjanuk’s church, St Vladimir Ukrainian Orthodox at that time. And those of other east European nationalities. Some of the older men were colleagues of Demjanjuk at the Ford plant, sitting quietly at their breaks, working hard without complaint, never getting into any kind of trouble with police, city officials and neighbours, flying the Stars and Stripes proudly outside their neat suburban homes, and putting their innocent children through college – without a word about what they did, or didn’t, in the war.

And why should they? The Cleveland these survivors of WWII went to was a paradise, untainted by the nationalisms of Europe where the 20th Century had seen hugely tainted by death, destruction and privation. Demjanjuk insisted he was a victim of misidentification and was a pawn in an international firestorm of retribution for the Holocaust. His trial in Jerusalem was watched there by Jews every day live on television. A national hatred engulfed him, and his Jewish lawyer had acid thrown on him after he pulled apart the faulty memories of elderly holocaust survivors who were so certain of his guilt but struggled with details of their memories of ‘Ivan the Terrible.’ One survivor, asked twice how he had got from Israel to Florida in the 1950s, insisted he had come by train.

Demjanjuk was finally freed in Germany when files from the Russian KGB, uncovered after the 1990 collapse of the Soviet Union, pointed to another man whose physical and recorded locations added to that of facial recognition experts who testified they did not match him. Demjanjuk died a free man, in a German care home in 2012. His children, and grandchildren, are free to live their lives as honest Americans.

(It has to be said, in mid-2022, that Ukraine’s image could not be higher in America, Britain and elsewhere in the world as the people of that country fight desperately against the invasion of many thousands of Russian troops).

Writing this memoir I can verify that there are some memories which are far from perfect. But at least I have the exact, yellowing copies of most of the stories I ever wrote over the 47 years of my journalism career.