Main Body

Chapter 7. Cleveland, 1975

Memory Flash: Ninth District Federal Court, Cleveland, Nov 24, 1975

Opening day of Reed vs Rhodes, the Cleveland schools desegregation case. (An end of the year start). And I am shocked. Truly shocked.

Nathaniel Jones, lead prosecutor for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), has just begun to recount how we got here, via the first desegregation trial of national significance: Brown vs Board of Education, Topeka, Kansas, 1954.

He tells us of a young black girl, perhaps five or six, in the witness box in that case, who was handed two dolls, one white and one brown, and was asked: “Which is the good doll, and which is the bad one?”

The girl pointed to the white doll as ‘good’ and the brown one as ‘bad.” Jones presented testing evidence that this was a common response from young black children.

As a white boy growing up in England with no exposure to the emotional depths of racial segregation I had never considered this aspect of the vestiges of slavery: the sense of inferiority from the color of a person’s skin. And that it could have had such an effect on a child so young.

There was more, but I was not aware of it until much later. The NAACP lawyers in Brown were using ground-breaking studies done in the early 1950 by black husband and wife New York psychologists Mamie and Kenneth Clark into the long-term pernicious effects on society of racial segregation in the US. (They had to paint one of the white dolls brown because manufacturers did not make any brown or black dolls then).

Shocking as the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ dolls were they also asked the kids which dolls looked most like them. Some of the children cried and ran out of the room because they did not want to identify with the brown dolls. They looked at TV and wanted blue eyes and blonde hair – and white skin.

The Clarks were so upset they delayed publishing their conclusions.

In 2010 the US TV news channel CNN commissioned a reproduction of the studies with 133 children, from a mix of racially segregated schools, this time including a substantial number of white kids. The results, reportedly, were strikingly similar. The white children maintained an intense bias towards whiteness. The black children, fortunately, had a more positive view of the dolls of their color.

Was that my highlight of 1975, starting at the end? Hardly, because the city was being prepared for school desegregation from March onwards by outsiders from cities who were already doing it. “Desegregation will come to Cleveland, city leaders are told” was one headline on a story I wrote. In order to make it work peacefully, the outsiders said, Cleveland’s leaders should start to plan for it now.

The message was given to business, church, education, news media and labor leaders by the police commissioner of Boston, the deputy superintendent of Detroit schools, an official of Memphis schools and an Ohio State University professor, invited to Cleveland State University by a Cleveland churches council. They heard from Ohio State University representative Prof Charles Glatt that Cleveland was one of the most segregated cities in the country and that blacks were trapped economically within the city, requiring an income of at least $10,000 a year to move to the suburbs.

I got a further taste of desegregation planning – or lack of it – from Miami Beach the next month, at a convention of some 20,000 school board members, including about 100 board attorneys. (And no, I didn’t actually get on to the beach in warm Miami. The meetings were all inside a convention center).

What I learned from Cleveland schools lawyer William Lahman and a couple of other board members was that they were not preparing any detailed busing plan and hoping instead to expand the “magnet school’ concept of city-wide students already attending the Aviation High School, Martin Luther King Vocational High Schools, Max Hayes and Jane Addams schools. Or even working up alternative schools in which youngsters spend part, if not all, the school week in a racially-mixed city-wide school in specific programs.

What I wondered about was the instability that was growing year after year on Cleveland schools and nationwide that were chicken and egg. Which came first, instability from vandalism, violence and lower standards in schools, or planning for racial desegregation that was encouraging richer white parents and their kids to move out of city schools by the thousands? The school board members at the conference wanted to deal with vandalism, which was rife and worsening by the day, more than busing. An educator from Chicago said she had told her superintendent she had not yet seen one of the system’s new schools. The superintendent told her: “You had better hurry because the place will be torn to the ground by the kids before you get there.”

In the big world outside Cleveland…. Inflation in the UK hit 24%; Bill Gates and Paul Allen started Microsoft; Patty Hearst, the kidnapped daughter of newspaper magnate Randolph Hearst, was caught in San Francisco; Muhammed Ali beat Joe Fraser in the ‘Thrilla in Manila’; Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa disappeared; Spanish dictator General Franco died; and the Vietnam War ended with that humiliating spectacle of the last Americans being helicoptered off the roof of the US Embassy in Saigon, with the victorious N. Vietnamese at the gates.

Oh yes, and at the movies we had the brilliant Godfather, Part 2; Peter Sellers’ hilarious Return of the Pink Panther; and Jaws, the shark movie in which just two musical notes would forever denote something sinister.[1]

Two notes that changed the film world: John Williams’ theme for “Jaws”

https://youtu.be/lV8i-pSVMaQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lV8i-pSVMaQ

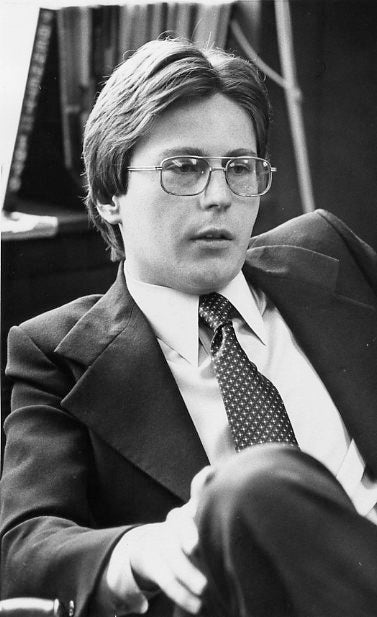

John Edward Gallagher was a 22-year-old in a hurry when he was voted onto the Cleveland School Board in November, 1973, the youngest board member ever, I believe. He was an outsider, a graduate of Catholic schools and, as the vice president of a west side premiums and promotions firm (his father was president) he said he was “not tied to a desk and certain hours.”

businessman and upstart young Cleveland School Board member – and the author’s best source.

I got on well with him from the start. We were on the same page in bringing news to the public and light to the darker corners of Dr Brigg’s fiefdom, and he wasn’t afraid to question and stand up for the ‘little guy,’ who was more inclined to be a Press reader than a Plain Dealer one. He was one of my main sources on the board. “Peter the Leader!” he would embarrassingly answer when I called him at 7.30am on Monday board meeting days, and then lay out for me all the main issues and decisions due to be taken that day. I had the best stories in the paper by noon, which the PD could rarely match.

Except once (that I know of). My PD oppo once wrote about the time he thumbed through the voluminous agenda of a meeting and saw the board was hiring a laborer who had the same name as a board member, ie the board was hiring the son of a board member when it was cutting teaching positions. I, apparently, was staring at the ceiling. “The Press reporter told me that I got him in big trouble because he had missed it,” later wrote the PD man of his own experiences.

Well, bully for you, Dick. If I got into trouble it was because it was such a rarity. The main schools stories were almost always in the Press before the PD. The editor kept me on the schools beat for six years.

I bet my story about Breaux Palmer beat your laborer, though. Septuagenarian Palmer was head of security for Cleveland public schools; utility man, “Best-dressed Negro man in the world” (a title he cherished), and Supt Briggs’ bodyguard. And with almost $30,000 a year the fifth highest-paid employee in the school system. I wrote about him on Page One of The Press on Feb 26 ’75 as part of a series about the cash-strapped school system’s top earners; custodians, principals, teachers and tradesmen.

“He walks into a school in sartorial perfection. Polished shoes, neatly tailored slacks and jacket, silk shirt, natty bow tie and his ever-present black wig of Chinese hair,” was my lede.

Palmer claimed 2000 hours of overtime – about 38 hours a week – and received $5,328 for 35,500 miles he travelled annually on his mobile-phone equipped car, most of those miles within Cleveland. With 115 security people under his control he was often seen late at night at the scenes of break-ins, school fires, and disturbances. “I will start my day at about 8.30am and many mornings I have to be in court giving evidence to the Grand Jury about various people,“ he told me. “We get eight or ten arrests a week for things like robberies, arsons and rapes.” In the afternoon he might go to a school to check out a security guard, and at 4.30pm go home for an hour to rest.

Then he’s out again, “a sort of cruising batman, waiting for trouble to hit one of the system’s 179 schools,” I wrote.

Palmer carried a weapon: a silver, two-shot Beretta pistol which he pulled from his back pocket when I interviewed him. At nights he carried a 38-calibre police special revolver. He’s a ‘special sheriff’s deputy’, badge No 2006, with powers of arrest. He was on call 24 hours a day and, when I talked to him, had spent six weeks night and day at racially-fractious

Collingwood High. “I remember one Sunday morning at 7 o’clock I had to go out and get sandblasters to remove a sign on a school wall that said “Kill all Niggers.”

Yes Breaux, but still… Those overtime records? Do you not spend a lot of time at night at an East Side bar, claiming this as overtime?

“That’s Lancer’s Steak House, 7707 Carnegie Ave,” he replied. “I’m in there every night. I go in about 10.30 and leave about 11.30. You see, one of my jobs is snooping. Most people there think because of the way I’m dressed I’m some kind of racketeer. I get all kinds of information. For instance, once we had a piano stolen from a school. I got it back from information obtained there.”

That, according to Palmer, was genuine overtime.

So, how old was he really? Either 62, 64 or 73 according to three job application records over the last 30 years that I dug out. “Well, the truth is, I really don’t know how old I am,” he said. “I think I’m 62 but let me check”. He didn’t have a birth certificate.

He went to the telephone, dialled a number to the school system’s personnel office and to the amusement of office girls, said: “This is Breaux Palmer. Would you check my application and tell me how old I am.”

A little bit of digging around and I came up with 73 as most likely.

Second in my series was about individual, named school employees who also made a lot of money, but below the $44,540 Briggs made in 1974. “Highest paid teacher was Edward Katz, who covered several elementary schools teaching music, paid a total of $22,502 on a $16,871 salary, the balance being work as a musical instrument repairman for the schools.

Third in the series was ‘How a custodian makes $27,000 a year’ -partly because of the square footage of the school, partly because vandalising students make him work overtime, and partly because they are solid union guys who know how to work the angles..

Memory Flash: Newsroom, March ‘75

Sometimes you just have to run a story EXACTLY as it was published. This one Is a celebration of the bizarre and ironic, that might be called a ‘drooper’ in the sex business

Headline:

“British Queen’s subject is sex”

By Peter Almond

One of the facts of life being an Englishman working for an American newspaper is I get stuck with every Limey who walks into the office.

There were the two fellows who had just rowed across the Atlantic; the chaps promoting Transcendental Meditation; the engineer who built an exact replica of the first railway engine.

The other day I got the prize fellow countryperson to date – a porno star.

It was the day gunman Eddie Watkins was threatening to blow up himself and six hostages in a West Side bank.

Half the staff seemed to be out on the story, leaving me, the education writer, to write up all the other traffic fatalities, armed robberies and suchlike.

Then the city editor walked over with a tall, slim girl wearing the most violent shade or orange hair I’d ever seen, a see-through dress and black fingernails.

“Peter, I’d like you to meet a fellow country-woman,” he said. “Tuppy Owens is her name and she’s a porno star.”

I was caught by surprise. Sex was not on my mind that crime-ridden morning and I’m afraid I said: “Oh yes, that’s nice.” He arranged to have her photo taken and left me to interview her, I assumed.

It was not an easy interview.

I mean, how much can one ask a porno star for publication in a family newspaper?

So I asked where she came from in England.

“Cambridge,” she said.

“Oh, really?” said I. “I went to school there for a while. I used to catch the 105 bus out of Drummer Street to Queen Edith’s Way.”

Her demeanor visibly changed.

“I used to catch the 103 bus out of Drummer Street,” she said, unenthused.

It turns out she is the daughter of a wedding photographer in Cambridge who sent her to the Perse School, the best grammar school in town. As I was the same age as her (29) I was therefore her contemporary, a fact she did not relish.

It took a little time, after she had said her elder brother was a vicar, to figure out she was a raving exhibitionist.

She won a Bachelor of Science degree at Exeter University in Zoology, went to Africa and Trinidad for a while, and in 1971 turned to pornography with a photo book on love positions.

Finding that she could make money out of her favorite hobby she wrote a couple more books – both soft-core because hard-core pornography is outlawed in England. Then she wrote her most successful book, “The Sex Maniac’s Diary, a Glossary of things sexual.” The diary includes information on the sexiest clubs in the world. There’s even a selection on Cleveland, stuck between Casablanca and Copenhagen.

Strangely, she rates Cleveland sexier than any of those other cities, naming a place the Vice Squad would love to hear about. Her information, she added, comes from journalists.

Her main interest in Cleveland, though, was to promote a porno movie in which she ‘performs’. It is a $25,000 production made in Holland called ‘Sensations’.

And that’s about all I can write for publication.

Except that she was actually embarrassed for me to interview her.

“A porno queen embarrassed?” I asked her.

“Well, yes,” she replied. “I can’t help thinking if we had met in Cambridge 15 years ago what a strange interview we would think this is.”

I couldn’t help thinking what a perfect subject she would be for a group of psychiatry students.”

I am genuinely sorry about that last sentence. It was a throwaway, an unintended insult, and one I regret. It says more about me than it does about her.

Because sex remained Rosalind (Tuppy) Mary Owens’ main occupation for the rest of her working life, in a vitally humane direction. In 1979 she started the Outsiders Club for socially and physically disabled people to find partners; she trained as a sex therapist in the U.S. gaining a diploma in Human Sexuality in 1986; chaired the Sexual Freedom Coalition in the UK and won several international awards for research and response to the poorly-recognized sexual needs of the disabled, disadvantaged, and lonely.

Almost 50 years later I wish I could find her to say sorry. (I keep doing that now I’m in my dotage).

Back to schools: Lack of money, in practice, remained THE big issue for almost all Cleveland area schools in ‘75. Voters had turned down more than half of the tax levy issues in the county the year before. The federal government was struggling with inflation. The only possible source was the state of Ohio. “If school superintendents in the Cleveland area start replacing their office photos of President Ford with that of Ohio Gov. James Rhodes the reason will soon become clear to the voters,” I wrote on Jan 14.

“Gov Rhodes, they believe, is either going to save their schools from economic disaster or education in 1975 is likely to suffer.”

Ohio was already known throughout the country as one of the worst in terms of state funding for schools. But would they budge for Cleveland, the state’s biggest and most troubled school district, with more students per teacher than any of the nation’s 20 largest cities – especially with Rhodes now named as the main defendant in the pending Cleveland schools desegregation case?

At the practical level at least enrollments were up at the area’s Catholic schools, mostly as some 5,000 children were taken out of the city’s public schools last year – providing additional tuition.

The only bright spot seemed to be a dramatic drive to improve the reading capabilities of Cleveland school children, following recommendations of a three-man panel of experts who recently examined the problem.

Memory flash: South Euclid, May ‘75

We’ve bought our first house, a ‘Country French’ design up the hill from Collinwood on South Belvoir Blvd, South Euclid. It has three bedrooms, a warm living room with a big picture window overlooking a steep, tree-filled 50-foot deep ravine where a tiny stream starts. To the side is a patio where I can build a tree-seat. To the front a long driveway and an expansive lawn on which there are 15 fully-grown trees. The garage has room for two cars. Anna can drive to work at her hospital.

After five years in a semi-basement flat we’re excited. We’ve bought an English Springer pup, named him Douglas (officially Sir Douglas Merriweather), and we’ve got a mortgage!

Or do we? We need to have a new thing called Flood Insurance, mandated to bank lenders by the government under a 1973 act which was still being rolled out across the country after some disastrous floods in Pennslyvania. Our new house was on the inside of a line drawn on a new map. The house next door was on the other side of the line.

This was going to cost us $100 for absolutely nothing, because we were up a hill where a flood couldn’t reach us.

“There’s no way this house is going to flood,” says a bank official who sent out two assessors to check the property. “The whole city of South Euclid would have to be under water before it reached the doorstep. But we have to follow the dimensions prescribed on this flood hazard map before we can give you a loan. And that house is within the flood hazard boundary.”

He produced Federal Insurance Agency Map No. H39 035 7670 01, a map of half the city of South Euclid, pinpointing our house exactly on the inside of the designated flood hazard area.

Perhaps its just as well I’m a reporter. I have a nose for pettifogging officialdom.

“I didn’t put those measurements in there,” says Stephen Hovancsek, South Euclid’s City Engineer. “This isn’t my map. The map I sent the Federal Insurance Agency had many more areas shaded in where there have been large numbers of flooded basements. This was supposed to be just a preliminary map, before a more detailed study could be made. It was supposed to allow people to buy flood insurance if they wanted it. I had no idea this map would cost people money.”

Who overrode the recommendations of the city engineer? I tracked the culprits to engineers for Gannett-Fleming-Corddory Inc, of Harrisburg, Pa, one of two companies in the U.S. assigned to the Federal Insurance Administration to prepare flood hazard maps. An engineer there admitted that the flood maps were drawn sight unseen, and based on topographical maps, using straight lines that run parallel to roads.

“It does look in this case it would take a lot of water to reach the top of the ravine,” he admits.

You’re not kidding! Another engineer, to whom I paid $25 for a letter to go to the bank says: “To reach your house the water would have to be half way up the Terminal Tower downtown.” ie the entire city of Cleveland under water. I wrote about this in the third person, revealing in the last paragraph that we were the couple in my story. “And we’re pretty mad about it!”

We got the mortgage, sans flood insurance.

School desegregation was a close second to Money, although everyone knew busing would cost a lot. I wrote hundreds of thousands of words about Reed vs Rhodes, the federal court case, between March 19 and Dec 26: forty three stories, most of them between Nov 13 and Dec 26.

I have them all before me, neatly photocopied and set out in a thick folder by someone on the Press staff for to be sent off to several national journalism awards contests under ‘breaking news.’

“This subject, which could have the most significant effect on Cleveland in its history, was given concentrated attention by Almond,” says the introductory blurb, which I didn’t write. “It is continuing with greater intensity into 1976.”

My words won a Special Citation from the Education Writers Association in 1976, with the addition of a long interview I did with the man who ordered busing, Federal Judge Frank J. Battistsi (more on that later).

Frankly, it gives me a headache to read through it all. I spent too many hours in court, talking to lawyers and writing it up – often updating it edition by edition as the case progressed each day. If it wasn’t for this folder I would have forgotten most of it, in detail anyway. I can’t even remember when the name of the case changed from Reed vs Gilligan (the former governor of Ohio) and Reed vs Rhodes, the name of his successor under whose name the case would forever be known.

I do remember the plaintiff, however, Robert Anthony Reed III. He was 17, had a large Afro, and was the first of 14 names on a list of plaintiffs put together by the NAACP. I interviewed him and brother Darryl – similarly tall and slim and also a plaintiff – at his home in Garfield Heights, a suburb but part of the Cleveland school district. With them was their mother Wyona Reed Willis and NAACP lawyer James Hardiman, who ensured they didn’t stray into any legally-tricky comments before the case had even started.

“Neither of them, “I wrote, ”gave any appearance of being militants, or anything else that might give satisfaction to ultra right-wing separatists. Indeed, Robert answered a question on former Black Panther leaders Eldridge Cleaver and Bobby Seale by asking “who?” He said he did not agree with the aggressive philosophy of Malcolm X.

I kept my opinions to myself, though, when Robert said his current hero was General George S. Patton, the World War II hero, who was white and came from a privileged background, especially after Reed and his family had made it clear he was himself the product of an all-black society and an all-black school. “I used to think all white people were middle class or rich,” he said. “I could see them on TV. It was like they were in another world.”

But more recently, he said, he had been working in a pancake house, with white kids his age “and they’re not so different to us.”

All very nicely presented as just normal black people who are no different to white people.

But the appearance was not the reality. Cleveland’s black leaders were far from satisfied they wanted the NAACP to take the desegregation case to court at all. As late as November, ’75, just one week before the start of the case in federal court, the city’s black leaders, led by City Council President George Forbes, were worried about the possibility of blacks being pitted against blacks in a long court battle. They knew their constituents liked neighborhood schools and feared busing.

So 30 of them came together in the top-floor Summit Room of William O. Walker’s Call and Post newspaper building to thrash it out with NAACP attorneys Nathaniel Jones, James Hardiman and Thomas Atkins, led by the Rev Austin Cooper, president of the Cleveland branch of the NAACP. It was a no-holds-barred meeting that dragged up the very basics of racial segregation. A meeting, I wrote, the likes of which has seldom been seen in Cleveland. It ended four hours later with an almost complete transformation of attitudes.

“When the history of Cleveland’s school desegregation efforts is finally written a significant section might well be entitled “The day the NAACP won over the Black leaders,” I wrote.

The meeting nearly collapsed before it started. Everyone there was black except for one, NAACP researcher Terry Demchak. There were whisperings, a few glances, and publisher Walker said: “This is a meeting for black folks. What we got to talk about is just between us.”

“Well, that’s too bad,” said NAACP leader Jones. “She’s part of our team, If she goes, we all go.”

As they prepared to leave George Forbes said: “You’re nothing but a bunch of phonies. Leaving? We figured you weren’t serious anyway. If you go, everyone in town’s gonna know the NAACP refused to sit down with Cleveland’s black leaders.”

All the NAACP team left the room, leaving a cabal of leaders huddled in conversation around Walker and Forbes, deciding this was not the time to get hung up on black ideology over the presence at a ‘blacks only’ meeting of one white woman. Jones and Cooper came back to present the NAACP’s case. School Board President Arnold Pinkney asked why the NAACP was using ‘outsiders’ to try to turn Cleveland into another Boston, where busing was wrecking the city’s school desegregation.

“Outsider? There’s no way you can call me or the NAACP outsiders in Cleveland!” said an outraged Jones who, until he became national general counsel for the civil rights organization was a United States attorney in Cleveland. “The NAACP has worked for blacks here for more than 50 years.”

Political posturing, replied Pinkney, implying that some in the NAACP had grudges against him. Going to trial to justify national policies and recoup its legal costs, said someone else. But when asked if the case could still be settled out of court Jones said it had already gone too far, there were constitutional violations that need to be corrected, he said. But when someone said: “Forget the courts and all this trial business,” the NAACP’s Rev Cooper exploded in fury.

“Forget the law? Forget the law?” he cried. “That makes me sick. Don’t you ever say that in my presence again. I come from a part of the country where black folks had their butts kicked all over the countryside and we had no recourse. But here we’ve got the law, and the court, to protect us, to assert ourselves”.

Jones talked about the history of desegregation and the kind of evidence used elsewhere, or manipulation of boundaries, transfer of teachers, construction of school buildings. “Cleveland is no different from elsewhere,” he said to a now-quieter audience. But still the images of busing remained. Jones kept hammering the point: “You’re talking about the remedy. Always the remedy. You can’t even reach that stage without having a declaration that what the School Board has been doing is in violation of the rights of every black child in this city. If you give up your rights and responsibilities to go to court on this subject, if you cop out in this area, you trade off your rights in other areas. You seal your doom in other areas. This thing is much bigger than a school bus.”

One by one people began to leave. The meeting ended on a somber note. The black leaders realized there was no turning back from the trial. George Forbes, the man who had expressed greatest hostility at the start, thanked Nate Jones for staying through the meeting.

“I was looking at some of the expressions on the faces of people here,” said Forbes. “Not only has my mind been changed, but I think a lot of minds have been changed.”

For some reason I now forget, this story did not run until the day after Judge Battisti ruled against the School Board ten months later, Sept 1, 1976. And then it was the paper’s main story.

Memory Flash: Cleveland Municipal Stadium, June 14, ‘75

So I said to Charlie as loud as I could: “How are you enjoying Cleveland so far?”

“Great,” said Charlie, twisting his drumsticks around his fingers as he lounged on a sofa. “A great city.”

“Did you know this is the town that came up with Rock ’n’ Roll – the NAME ‘rock ‘n’roll’?” I shouted, unable in all the bedlam to think of something witty, sharp, amusing or truly engaging. Not even “Did you know your car is on a double yellow?” would do it.

Charlie looked a bit surprised and said ‘Oh.’

Then a Roadie stepped in to say something to him, and together they turned to examine a drum, and that was Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones lost to me.

I only had five minutes with the Greatest Rock Band in the World, about to perform a massive gig in the raucous, packed-out 82,000-seat stadium, one of only two press reporters given access to the Stones in their dressing room beneath the building (the other, probably, being the legendary Jane Scott of the Plain Dealer – the’ oldest rock critic in the world.’ I had The Press slot because I had already declared in print my affection for the band from its earliest days, and because I was English the newsdesk thought I might wheedle a little more out of them than Jane, or own Bruno Bornino.

But it was bedlam both outside and inside the stadium, including the dressing room. Mick Jagger was in intense conversation with a woman about microphones. Bill Wyman was curled up in an armchair, his eyes closed and plugs in his ears; Ronnie Wood, newest Stone, wasn’t interested in anything but tuning his guitar; and Keith Richards wasn’t anywhere to be seen. When my five minutes was up Ms PR escorted me out of the stadium.

T’was ever thus. I had interviewed the Stones eight years earlier, in 1967, backstage at the Odeon Theatre in Leeds, England, and it wasn’t much different then. That time I found Keith Richards to be boring, Brian Jones (who drowned, accidentally, in a swimming pool) missing, Charlie Watts downright insulting and Mick Jagger drunk and truculent and sporting a forehead cut inflicted the night before by a ’fan’ who threw a beer can. “The only one still retaining a shred of civility,” I wrote for the Yorkshire Evening Press at the time, “was Bill Wyman, who seemed the least affected by the international fame.’

This time, and again without satisfaction, I faded away back to the paper on nearby E.9th St.

The next morning only my description of the Stones’ preparations made it into the paper (the latter part was put on a page filled with three large schools stories by me, as if the Rolling Stones somehow had a direct connection to Cleveland schools). Anna and I did get to see the show, however, and it was as good as we expected (although she’s not really into Heavy Metal).

After the Ten Cent Beer night at the stadium a year earlier, police were massed in considerable numbers for days before the event, 40 police officers alone dealing with ticket scalpers, 110 off-duty police assisting the stadium security, 79 dealing with illegal parking. Even so, I remember two young lads died when they fell of the stadium’s external structure.

A lot of the youngsters at that Stones concert had finished school for the year barely a week earlier, ending a school year marked for its unparalleled lawlessness across Greater Cleveland. A five-part series on it started on June 9 and declared that thousands of teachers and administrators were ‘counting the cost of one of the worst years of violence and vandalism in the nation’s history.’ In Cleveland 40 students had been expelled for carrying -and sometime using – guns, knives and other weapons, ‘more than the schools expelled over the last 30 years combined.’

Herman Imel, properties control supervisor of Cleveland’s public schools, said that already by spring vandalism was up 25% over last year. “I am discouraged,’ he told me. “If this is any indication, we’re in for a very bad summer. As the days get longer, vandalism gets worse”.

Our photographer Herman Seid took a heartbreaking picture of students at Adlai Stevenson elementary school hunting through a pile of damaged pictures ripped from walls, trying to see if their own artwork was damaged. Seven boys, aged 10 to 16, were arrested after they smashed windows, ransacked five classrooms and destroyed artwork.

Across Cuyahoga County increasing numbers of children were simply leaving their desks and walking out – or not going to school at all. A teacher at Cleveland Heights High said she was a substitute who came to teach a class and several students just walked out. “They saw I was a substitute so they decided to walk out,” she reported. “I told them I would report them to the principal. They just laughed. They could care less.”

On one recent Monday at Glenville High School in Cleveland 667 of the school’s 2300 students – almost 30% of the total – were marked absent. Almost any spring weekday could find hundreds of youths who should be in school picknicking in Greater Cleveland’s Metroparks.

“I’m sorry to say that today the kids are looking jaded even in kindergarten,” Mrs Muriel banks, a learning disabilities teacher at Gilbert Elementary school, told me. “I don’t know what’s wrong. It’s rough. Even in kindergarten kids are rude, their language is terrible. All grades have kids who miss school or walk out of a classroom without being dismissed.”

What’s the answer? Big, controversial question. I spent a lot of time asking experts from across the country for their recommendations. Some said they should do as Catholic schools and return to dress codes, even if only a couple of days a week when they are required to wear school uniforms. Some said the school leaving age should be lowered from 18 to 16, or even 14. Corporal punishment wasn’t an alternative, although some Ohio schools still used it.

Ohio was one of only five states in America that had compulsory school attendance until 18. The others were Hawaii, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah and Washington state; none with big city problems comparable to Cleveland. David Moberly, former superintendent of Cleveland Heights schools, who moved to head Evanston school district in suburban Chicago, said: “I feel that if the kids here were forced to stay in school until they were 18, like we had in Cleveland heights, we would really have to fight a battle.” But with few jobs to go to at 14 or 16 would these dropout kids be targets for troublemakers and criminals?

Personally, I thought that the sheer size of most high schools – 2,500 to 3000 students, while providing wide-ranging and cost-effective facilities – made American high schools too impersonal, and too formulaic. But what sort of an expert was I, from a foreign country?

Memory flash: Walhonding, Ohio. July 1975

We’re back at one of our favorite camp sites, next to the Mohican River. The six of us – Anna, me, Jim, Marcy, Al and Nancy, have had a delightful day slowly paddling downstream for 15 miles, looking out for the Sparrow Hawks, finches, Egrets and, of course, the state bird of Ohio, the Red Cardinal. We’ve grounded a couple of times, trailed our fingers in the water, eaten our sandwiches and listened to the quiet.

Now we’re sitting around a campfire eating marshmallows, drinking wine and someone is reading a creepy story aloud. If Daniel Day-Lewis doesn’t leap out of the darkness with a blood-curdling scream I wouldn’t be surprised.

But what IS that noise? A slight hissing from the darkened river.

“Can you hear that noise?” say I.

Someone points a flashlight towards the river. There are MILLIONS of white-looking flying bugs streaming down the river.

“Fireflies!” says Jim, our expert for all things outdoors (since he is, indeed, The Press’ Outdoors Writer).

“I’ll turn a headlight on them,” say I, thinking we could see this annual migration better.

“NO! Don’t!” says Jim. ”They’ll turn this….!”

He didn’t get to say “way”! because they were already doing it. Attracted by my car headlights the mllions of fireflies automatically turned left towards the brightest light, which happened to be adjacent to our campfire. Argghhh! I quickly turned off the headlights and the fireflies- after some flappy confusion that seemed to involve marshmallows – rediscovered their original march upriver.

Another narrow escape for Yours Truly. Phew!

One thing about being an education writer in the 70s was that it suggested my education included a significant understanding of science and mathematics. It doesn’t, and it certainly didn’t in March, 1975, when I was asked to write a piece about the new phenomenum of calculators in schools.

Hand-held calculators had only become available in 1972, when they quickly became popular with businessmen on airplanes, housewives in supermarkets, taxpayers at home. But for sixth graders (11-year-olds) at schools?

Driven partly by a report by the quasi-government National Advisory Committee on Mathematical Education (NACOME) eighth graders and above across the country were recommended to have access to calculators for all classwork and exams. This caused ructions in American schools and with parents. Kids being told they can use a MACHINE for the four basics: add, subtract, multiply and divide? How is THAT going to help children whose brains can barely add 10 and 5 together?

But slowly, school district by school district, Cleveland area children had started to get them, on the principle that they help you get over the basics and on into more advanced math much quicker and with fewer mistakes – 30 seconds for basic calculations against several minutes working it out on paper, with a chance of getting it wrong. I remember at school in the 60s that I failed an exam involving quadratic equations because I had mentally added or subtracted one basic figure that produced a wrong answer.

Ten years later, it was the Litronix 2230 which could instantly do the basics, with a square root function, a memory function and an error function. Some of the cheaper hand-helds with basic functions cost only $20 each ($100 in 2020), within the budget of some of the wealthier schools in the area. Shaker Heights’ Dad’s Club bought $500 worth of six-digit calculators for the school system’s 6th graders which spent two weeks at each of the city’s nine elementary schools. Candy sales at Mooney Junior High in Cleveland bought 24 calculators at $28 apiece.

The arguments were building for and against. “Generally, they should not be used by youngsters who still do not understand why the calculator does what it does”, the head of the Ohio Council of Teachers of Mathematics, told me. “In Junior high I think they should be used as soon as they are fair to all kids. By the ninth grade all students should be required to use them”.

In October my mother came to visit our new house in South Euclid. “MUCH better than that flat,” she said. We went off traveling: via York, Pennsylvania where, of course, I took a picture of Mom standing next to the York sign so she could show it to her friends and family back in York, England. Not exactly a suitable response to her gift to us of a large, limited-edition encased ceramic plate marking the 1700th year of York’s founding by the Romans. And then to Gettysburg, to Washington DC, and Jamestown, Virginia where, besides copies of the original ships that crossed from England in 1607, we discovered the still-new concept of ‘factory outlets,’ retail stores which were just a shade below top-quality, and thus attractively cheap.

Then on to North Carolina’s Outer Banks, where we discovered The Wind which helped the Wright Brothers get their Flyer into the air at nearby Kill Devil Hills.

We camped at Pea Island, my mother lying between Anna and me in our sleeping bags as the wind shook our tent all night and where, in the morning, Mum was filmed briskly trying to catch the wind-caught cornflakes as they were poured from box to bowl -a futile endeavour. We were grateful that the wind had dropped considerably when I put her into our Sea Eagle inflatable canoe and I pushed her out to sea for her first-ever paddle. Fortunately, only Anna ever knew of my mounting panic as she started drifting away.

The next month came a reminder that wind and sea disasters are not exclusive to oceans like the Atlantic, but can reach deep inland to the Great Lakes.

On Nov 10, a month after Pea Island, the 26,000-ton iron ore carrier Edmund Fitzgerald sank in a ferocious storm on Lake Superior. All 29 of its crew died. It was not the worst disaster of the Great Lakes (that was undoubtedly the sinking of the SS Eastland in 1915, which rolled on its side while docked on the Chicago River, killing 848 passengers and crew). But the Edmund Fitzgerald is much more remembered because the wreck lay undetected at the bottom of Lake Superior for many years, because none of its crew were recovered, and mostly because of a haunting song: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, by Gordon Lightfoot.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6DUFPNILvM

It’s a long, toughly-emotional folksong that echoes a saying of Lake Superior’s Chippewa tribe:

“The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they called Gitche Gumee

Superior, they said, never gives up her dead

When the gales of November come early.”

And its connection to Cleveland? The Edmund Fitzgerald called on Cleveland and most of the Great lakes’ steel-making ports (despite what Lightfoot sings, however, it was NOT headed for Cleveland on Nov 10,’75 but to Detroit). It was owned by the Cleveland-based firm Oglebay Norton and about a third of the crew came from the Cleveland area, including its senior officers.

And for one newly-naturalized English Clevelander five years later it would be known as the tune to rewritten lyrics by Bobby Sands, a leader of the Provisional IRA who died on hunger strike in the Maze prison, Belfast, in May, 1981, a major moment of the barely-settled multi-generational Troubles between Catholic Irish and Protestant Ulsterman and women. Sands’ song: ‘Back Home in Derry,’ described the voyage of Irish convicts to Australia after the rebellion of 1803.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iheirlzWZuY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iheirlzWZuY

Almost nothing was said at his death about what he was convicted for.

But I knew what Sands had done, because I was there three hours after he and his gang blew up the storeroom of the Balmoral Furniture Co in Dunmurry, Northern Ireland in October, 1976, almost a year after the Edmund Fitzgerald. My story that Nov 8 was the lead on Page 1 of the Cleveland Press, the first of a six-part series I wrote for the paper at what was to become known at the peak of The Troubles.

It was also a memorable moment for Anna, who was in a bedroom of a Dunmurry hotel – trying to catch an escaped parakeet and awaiting my return from a flak-jacketed patrol with the British Army – when the explosions shook her window and soldiers ran across the neighboring golf course in pursuit of what turned out to be Sands and his IRA gang.

At his death in May, 1981 The Press re-ran that story of 1976, describing for all suburban housewives how Mrs Agnes Nicholls, ‘a homey, middle-class woman living in a semi-detached house in a suburb, has just discovered that she lives in a war zone.” She had been upstairs making beds when she heard sharp cracks outside, watched police and soldiers running and shouting and shooting “bang, bang, bang, very fast’. A man lay wounded by her front gate, she found the gun he threw away, then the bombs went off. The four others, including Sands, were caught in a car shortly afterwards.

That’s the thing about terrorists: you never know where and when they will strike.

More about The Troubles in the next chapter.

Memory Flash: S. Belvoir Blvd, South Euclid, Xmas 1975

We’re having a house-warming party, proudly showing off the stressed late-medieval heavy dark oak hutch and extendable solid oak dining table with Windsor chairs that we bought new from Higbees store downtown. And the new carpeting and neat low circular table in the living room. And all our little knick-knacks brought over from England, including the set of lovable little Golliwogs.

Little WHAT?

Golliwogs. To quote from Wikipedia[2]: “The golliwog, golliwogg or golly is a doll-like character – created by cartoonist and author Florence Kate Upton – that appeared in children’s books in the late 19th century, usually depicted as a type of rag doll. It was reproduced, both by commercial and hobby toy-makers, as a children’s toy called the “golliwog”, a portmanteau of golly and polliwog and had great popularity in the UK and Australia into the 1970s. The doll is characterised by jet black skin, eyes rimmed in white, exaggerated red lips and frizzy hair, a blackface minstrel tradition’.

Anna’s mother had made them for her when she was a child. She played with them and slept with them, along with her teddy bears and other dolls. They were well-established in British culture, written in the Noddy children’s books of Enid Blyton and appearing on every jar of Robertson’s jam. The firm would even send you a Golliwog brooch. I had one once.

We never thought anything of it – until that day in our own house when we saw a few of our black friends standing close together and looking with serious expressions at our Gollies. They said nothing to us, but smiled politely. It was only later that we learned these little dolls were offensive to people of color in America.

To quote Wiki again: “The doll is widely recognized as racist. While some people see the doll as an innocuous toy associated with childhood, it is considered by others as a racist caricature of black Africans alongside pickaninnies, minstrels, and mammy figures. The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia described the golliwog as “the least known of the major anti-Black caricatures in the United States”

Oh dear. We’re not in Kansas any more, Honey Bun, I thought as I prepared for the New Year and more months of school desegregation court battles.

- "Two Notes That Changed the Film World: John Williams' Theme for 'Jaws.' " CSO Sounds and Stories. June 8, 2017. https://csosoundsandstories.org/two-notes-that-changed-the-film-world-john-williams-theme-for-jaws/ ↵

- "Golliwog." Wikipedia. April 4, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golliwog ↵